Master?。铮妗。牛睿纾欤椋螅琛。幔睿洹。粒恚澹颍椋悖幔睢。蹋椋簦澹颍幔簦酰颍?/h1>

2009-06-08 08:51DongYinfang

文化交流 2009年2期

Dong Yinfang

I became acquainted with Yuan Kejia (1921-2008) in 1983. A high school graduate ambitious to be a writer, I was overjoyed when I learned that Yuan Kejia, a master of English and American literature, was a native of my hometown Cixi. I made bold to write him a letter, asking him for the secrets for literary success. In September, I received his reply from Beijing. He said that he had had no contact with the literary circles of his hometown and wished to hear from me more in the future. Upon my request, he wrote an essay about his hometown memories. It was published in October, 1983 issue of Cixi Art and Literature, together with a brief biography of Yuan Kejia that I penned. At that time, Yuan was a researcher at the Foreign Literature Research Institute of the China Academy of Social Sciences and professor and tutor of doctoral students.

Yuan Kejia began to publish poems in 1941. He was one of the nine poets that appeared together in a poetry anthology called “A Collection of Nine Leaves” published in 1948. The nine young poets who rose to national fame because of the collection are regarded as a phenomenon in the history of Chinese literature, because they represented a fresh trend and accomplishment in exploring new paths away from traditional poetry.

Yuan Kejia was more than a poet. He was the editor in chief for “Selected Works of Modern Foreign Literature”, the first ambitious anthology of modern foreign literature after 1949. The introduction he wrote for the anthology is hailed by critics for its academic value.

It was only natural that Yuan became the honorary president of the Seven Leaves Poetry Society, established in October, 1985, a group that included me and other six local young writers in Cixi, now a part of Ningbo City in eastern Zhejiang Province. We published a poetry journal at a regular interval and Yuan managed to find time to read our poems and comment. He wrote us a letter in celebration of the first anniversary of the society, encouraging us to explore and write better. In a letter to me, Yuan questioned our poetic philosophy and techniques and advised us to study foreign modern poetry, saying that the full exposure to these poems could open our eyes to literary possibilities and that we needed to digest what we read.

In 1994, I put together and published at my own expense a collection of the poems I had written over a period of ten years and sent Yuan a copy. He wrote a long commentary. I had a sleepless night after reading the candid criticism.

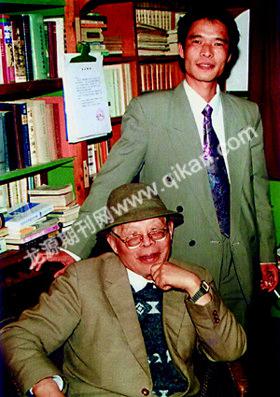

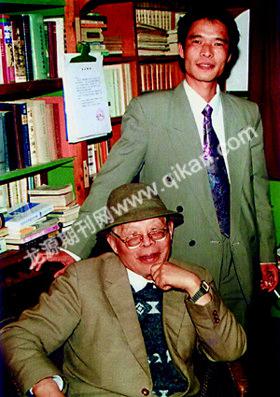

I visited him at his home in Beijing on October 11, 1994. He was 70 years old that year. His was a 2-room apartment, minimally but neatly decorated. The impressive bookshelves were everywhere. It was the first time I had seen a private library full of original foreign books.

I received encouragement from Yuan when I shifted my literary focus to the local history and culture of Cixi. In 1985, I wrote a book about local writers and scholars. Yuan Kejia wrote me an encouraging letter about my book. After the Cixi County Annals was released, he was very pleased to write us a letter expressing his congratulations and appreciation.

My collection of books authored by writers of Cixi origin includes more than 20 books by Yuan Kejia. All carry his autograph.

He retired to New York in the late 1990s and lived with his daughter. Tortured by diseases in his evening years, he still carried on his academic activities. He wrote me in 2000 about the latest editions of his translations of Robert Burns and William Butler Yeats and his research on European and American modern literature.

On the noon of December 27, 2007, I received a call from Yuan Xiaomin, the daughter of Yuan Kejia in New York. She spent nearly half an hour talking about the poor health of her father and his wish to see the publishing of a collection of his works when he was still alive. It turned out that the father and daughter had put together a six-volume collection of his works. I talked with Yuan Kejia. He was a little indistinct in speaking, but I understood him well. He needed our assistance to get his collection published. We agreed that the daughter would fax me a plan and brief introduction so that I could talk to the people in charge.

After a week in Northeast China in November, 2008, I came back home. Going through the newspapers that had accumulated during my absence, I tumbled upon his obituary. Although I had known about his poor health, I was still stunned and grieved by the news of his death. His life flashed through my mind: a poet in his youth, a translator in his middle years, and a scholar of foreign literature in the second part of his life. □

Dong Yinfang

I became acquainted with Yuan Kejia (1921-2008) in 1983. A high school graduate ambitious to be a writer, I was overjoyed when I learned that Yuan Kejia, a master of English and American literature, was a native of my hometown Cixi. I made bold to write him a letter, asking him for the secrets for literary success. In September, I received his reply from Beijing. He said that he had had no contact with the literary circles of his hometown and wished to hear from me more in the future. Upon my request, he wrote an essay about his hometown memories. It was published in October, 1983 issue of Cixi Art and Literature, together with a brief biography of Yuan Kejia that I penned. At that time, Yuan was a researcher at the Foreign Literature Research Institute of the China Academy of Social Sciences and professor and tutor of doctoral students.

Yuan Kejia began to publish poems in 1941. He was one of the nine poets that appeared together in a poetry anthology called “A Collection of Nine Leaves” published in 1948. The nine young poets who rose to national fame because of the collection are regarded as a phenomenon in the history of Chinese literature, because they represented a fresh trend and accomplishment in exploring new paths away from traditional poetry.

Yuan Kejia was more than a poet. He was the editor in chief for “Selected Works of Modern Foreign Literature”, the first ambitious anthology of modern foreign literature after 1949. The introduction he wrote for the anthology is hailed by critics for its academic value.

It was only natural that Yuan became the honorary president of the Seven Leaves Poetry Society, established in October, 1985, a group that included me and other six local young writers in Cixi, now a part of Ningbo City in eastern Zhejiang Province. We published a poetry journal at a regular interval and Yuan managed to find time to read our poems and comment. He wrote us a letter in celebration of the first anniversary of the society, encouraging us to explore and write better. In a letter to me, Yuan questioned our poetic philosophy and techniques and advised us to study foreign modern poetry, saying that the full exposure to these poems could open our eyes to literary possibilities and that we needed to digest what we read.

In 1994, I put together and published at my own expense a collection of the poems I had written over a period of ten years and sent Yuan a copy. He wrote a long commentary. I had a sleepless night after reading the candid criticism.

I visited him at his home in Beijing on October 11, 1994. He was 70 years old that year. His was a 2-room apartment, minimally but neatly decorated. The impressive bookshelves were everywhere. It was the first time I had seen a private library full of original foreign books.

I received encouragement from Yuan when I shifted my literary focus to the local history and culture of Cixi. In 1985, I wrote a book about local writers and scholars. Yuan Kejia wrote me an encouraging letter about my book. After the Cixi County Annals was released, he was very pleased to write us a letter expressing his congratulations and appreciation.

My collection of books authored by writers of Cixi origin includes more than 20 books by Yuan Kejia. All carry his autograph.

He retired to New York in the late 1990s and lived with his daughter. Tortured by diseases in his evening years, he still carried on his academic activities. He wrote me in 2000 about the latest editions of his translations of Robert Burns and William Butler Yeats and his research on European and American modern literature.

On the noon of December 27, 2007, I received a call from Yuan Xiaomin, the daughter of Yuan Kejia in New York. She spent nearly half an hour talking about the poor health of her father and his wish to see the publishing of a collection of his works when he was still alive. It turned out that the father and daughter had put together a six-volume collection of his works. I talked with Yuan Kejia. He was a little indistinct in speaking, but I understood him well. He needed our assistance to get his collection published. We agreed that the daughter would fax me a plan and brief introduction so that I could talk to the people in charge.

After a week in Northeast China in November, 2008, I came back home. Going through the newspapers that had accumulated during my absence, I tumbled upon his obituary. Although I had known about his poor health, I was still stunned and grieved by the news of his death. His life flashed through my mind: a poet in his youth, a translator in his middle years, and a scholar of foreign literature in the second part of his life. □