Determinants of infant behavior and growth in breastfed late preterm and early term infants: a secondary data analysis

Xinzhuo Zhang · Jinyue Yu · Zhuang Wei · Mary Fewtrell

Abstract Background Late preterm and early term infants are at increased risk of poor growth,behavioral problems,and developmental delays.This study aimed to investigate the impact of maternal and infant characteristics,feeding practices,and breastmilk composition on infant behavior following late preterm and early term delivery,and to evaluate the association between infant behavior and growth.Methods Data from 52 Chinese mothers and their late preterm/early term infants participating in the Breastfeed a Better Youngster study were used.Maternal and infant characteristics were collected using questionnaires at 1 week postpartum.Breastmilk macronutrient content was measured using a human milk analyzer,and infant behavior was assessed using a 3-day infant behavior diary at 8 weeks postpartum.Feeding practices were collected at both time points using questionnaires.Multivariate models were used to assess associations between potential predictors and infant behavior and between infant behavior and growth.Results Exclusive breastfeeding was associated with greater sleep duration (P =0.02) and shorter crying duration (P =0.01).Mothers with a vocational education reported greater distress duration (P =0.006).Greater colic duration was associated with higher maternal annual income (P =0.004).There was no significant association between infant behavior and growth(all P >0.05).Conclusions Exclusive breastfeeding might promote more favorable infant behaviors in late preterm/early term infants,while the development of infant distress behaviors was associated with some maternal characteristics (maternal education and annual income).However,due to the limitations of diary methods,determinants of infant behavior should ideally be assessed using more objective measures in larger samples.

Keywords Breastfeeding · Growth and development · Infant behavior · Premature infant

Introduction

During the first two years of life,infants adapt to the postnatal environment,ingest food to grow,and develop sleep–wake patterns [1].In the first months,the main infant behaviors are sleeping,crying,and feeding.There is growing evidence that behavioral problems in early infancy,such as excessive crying,sleeping problems,and feeding difficulties,are associated with growth in infancy and childhood,especially for infants born preterm [1–4].

Sleep is an essential function for proper growth and development [5].As infants develop and start to interact with their surroundings,increasing awake times can contribute to increased energy intake,especially when parents tend to use food to soothe their crying infants [6].Since human infants are born immature and have to elicit attention from caregivers for survival,crying is a powerful signal communicating their feelings and needs [7–9].Hunger in mammals induces vocal begging behavior,where the infant signals its need to the parent [10].Crying is also metabolically costly and may adversely affect offspring growth due to increased metabolic rate and decreased sleep [10].Breastfeeding may facilitate infant sleep through the effect of sleep-promoting compounds in breastmilk [11].However,mothers who experience difficulties in breastfeeding may have higher levels of stress,which can negatively impact milk let-down and decrease milk supply to infants [12].In some cases,infant behavior may influence maternal perception of milk supply,affecting decision-making around infant feeding [13].When breastmilk is not sufficient or available,infant formula milk is the only safe alternative [14].However,formula milk can be associated with a higher incidence of morbidities,notably infection,in preterm infants [15].

Specific behaviors of premature infants differ from those of healthy full-term (FT) infants.Premature infants spend around 90% of their time sleeping compared to 70% of FT infants [5].They also have a higher risk of excessive crying during the first months,primarily due to colic [16].In addition,problematic feeding is more prevalent among premature infants,although the determinants are still not clear [4].Previous studies have focused on the impact of maternal demographics,stress,and depression on behavioral problems in premature infants.For example,mothers of premature infants with less social support and lower self-esteem are likely to have less ability to read infant cues,leading to increased infant crying [17].Moreover,mothers of premature infants are more vulnerable to infant crying and exhibit more psychological distress than mothers of FT infants [18].Mothers with higher levels of stress also show more sensitivity to their infants,which possibly affects infant temperament later on [19].

Late preterm (LP) infants born at a gestational age of 34 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks account for about 75% of all preterm births [20].Although early-term (ET) infants born between 37 0/7 and 38 6/7 gestational weeks are not considered preterm,they are more immature than FT infants [20].LP and ET birth may pose a risk to infant growth due to physiological immaturity and increased morbidities [21].However,most developmental research has focused on more severely premature infants instead of these “near term” infants,although both LP and ET infants are at an increased risk of behavioral problems and delayed development when compared with FT infants [21].To address this research gap,the objectives of this study were to investigate determinants of infant behavior(mainly sleeping and crying) and the association between infant behavior and growth (weight and length gain) in LP and ET infants.

Methods

Design

This was a secondary data analysis performed using data from the Breastfeed a Better Youngster (BABY) study,a randomized controlled trial conducted in Beijing,China [22,23].In the BABY study,mothers and infants were screened using the following inclusion criteria:(1) Chinese,primiparous,non-smokers;(2) planned to exclusively breastfeed for at least two months;(3) singleton infant,born between 34 0/7 and 37 6/7 gestational weeks;and (4) mother and infant generally healthy (free of serious diseases expected to affect breastfeeding or infant growth).Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Children’s Hospital (ID: 2018–167) and University College London (ID:12681/002).All participants provided written informed consent at recruitment.

Samples

Out of 96 mother-infant pairs enrolled in the BABY study,52 were eligible for our analysis (38 and 6 were excluded due to incomplete infant behavior diaries or incomplete diaries <1 full-day,respectively).For the current analyses,a post hoc calculation estimated that the minimum required sample size for one explanatory variable at 80% power with a significance level of 0.05 and a small effect size (Cohenf2=0.2) would be 42[24];therefore,our sample size was sufficient for simple regression.

Predictor variables

Maternal characteristics

Maternal age (in years),education,and annual income were collected at 1 week postpartum from a demographic questionnaire.Maternal stress (ranging from 0 to 40) was estimated at 8 weeks postpartum using the Chinese version of Cohen’s perceived stress scale [25].

Infant characteristics

At 1 week postpartum,infant weight was measured with an electronic scale (measurement is presented in outcomes),while sex and gestational age (rounded to the nearest whole week) were collected from the demographic questionnaire.

Feeding practices

Information on infant feeding practices was collected from the demographic questionnaire at 1 week postpartum and a breastfeeding questionnaire at 8 weeks postpartum.The feeding practices collected included exclusive breastfeeding (EBF),mainly breastfeeding,formula feeding,and mixed feeding.Data were further dichotomized as “EBF” and “not EBF”.EBF refers to those who received only breastmilk from the day of recruitment to 8 weeks postpartum.

Milk composition

Foremilk samples were collected either by manual breast expression or by a hand pump (Philips Avent,Netherlands) at 1 and 8 weeks postpartum.Fat,protein,and total carbohydrate contents in breastmilk were measured using a mid-infrared milk analyzer (HLIFE,China).Prior to analysis,samples were thawed at room temperature (27–29 °C),and the analyzer was set up in calibration mode for homogenized human milk,following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Outcome variables

Infant behavior

Infant behavior at 8 weeks postpartum was measured using a 3-day infant behavior diary translated into Chinese.The diary consisted of five categories of infant behavior: sleeping,feeding,crying,fussing,and colic,with specific definitions of each behavior explained in the questionnaire [22,26].Crying was defined as prolonged clusters of crying or an expression of pain.Fussing was defined as making an unpleasant sound without excessive crying.Colic was defined as gastrointestinal symptoms or intense,inconsolable crying or fussiness.Mothers recorded one dominant infant behavior every 15 minutes over three consecutive days.In the analyses,three infant distress behaviors (crying,fussing,and colic) were further grouped as a new variable “distress”,calculated as the sum of the three distress behaviors.Diaries included in the analysis had at least one full-day infant behavior,and 24-hour infant behavior was used for further analysis based on the following formula (infant behavior: sleeping,feeding,crying,fussing,colic,and distress):

Total duration of infant behaviour(minute)

Number of recording days(day)

=Average duration of infant behaviour(minute∕day)

Infant growth

At 1 and 8 weeks postpartum,infant weight and length measurements were conducted following the methods described by the World Health Organization [27].Weight was measured to the nearest 0.001 kg and length to the nearest 0.1 cm with an electronic weight and length scale (Betterren-FSG-25-YE,Shanghai,China).Each measurement was repeated three times,and the mean value was taken.Sex-and gestational age-adjusted standard deviation (SD)scores for infant weight and length were calculated based on the INTERGROWTH-21st preterm postnatal growth standard [28].

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS (version 27.0) was used for statistical analyses,withPvalues less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.Univariate linear regression analyses were used to determine associations of maternal age and stress score,infant weight and sex,feeding practices,and milk composition with the duration of infant behavior (sleeping,feeding,crying,fussing,colic,and distress) at 8 weeks.ANOVA was conducted to predict infant behavior from maternal education,annual income,and gestational week.Those variables statistically significant in univariate analyses were subsequently selected for ANCOVA to control for potential confounding effects.Since not all mothers reported infant distress behaviors,two sets of analyses were performed,one including those who reported these behaviors while the other included all infants with those who did not report any distress behaviors coded as zero.For each outcome category,sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the impact of the number of recording days as an additional variable in the multivariate analysis.Spearman’s correlation was used to investigate associations between infant behavior (sleeping and distress) and infant growth (as changes in SD-weight and SD-length from 1–8 weeks).

Results

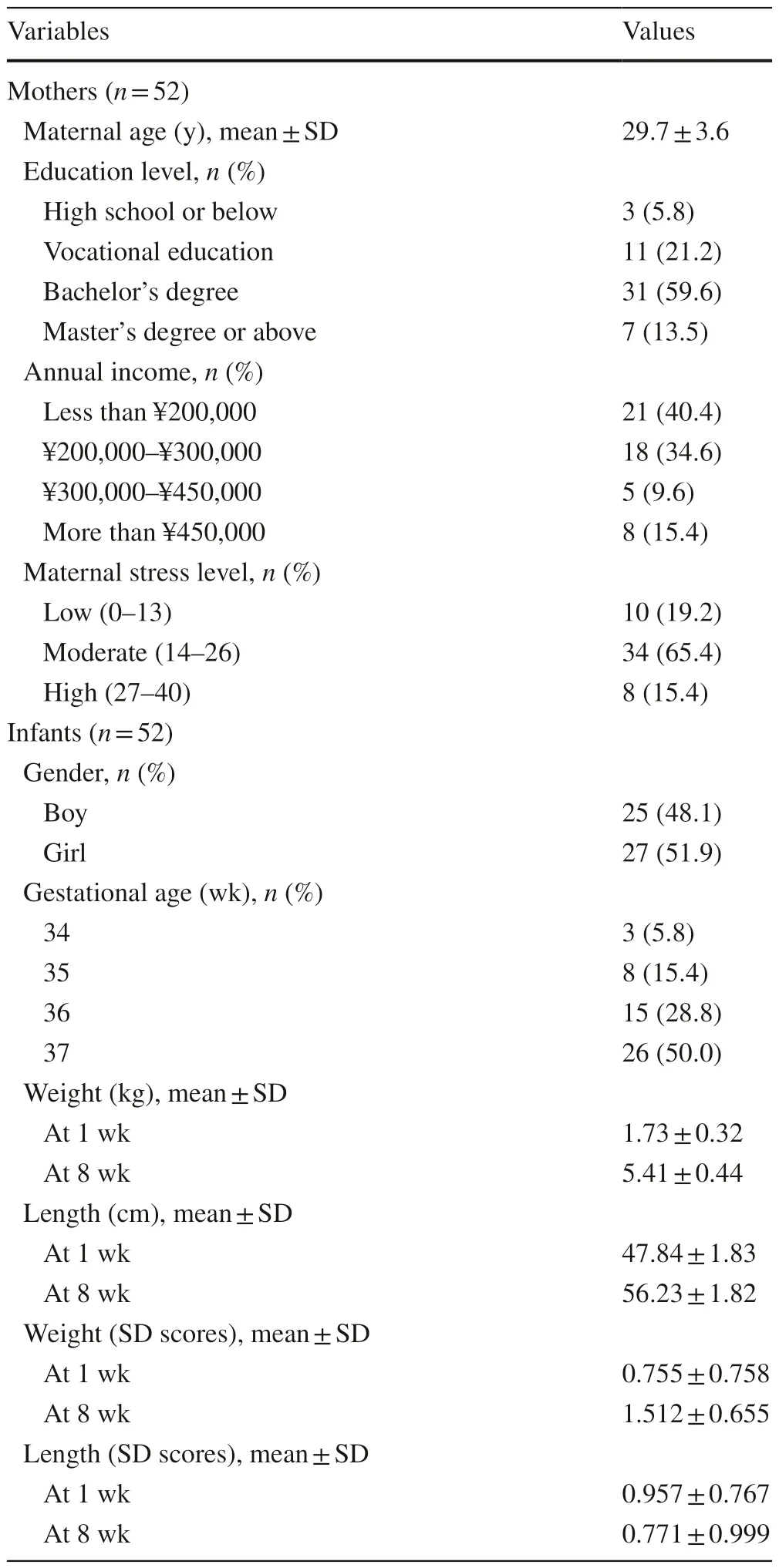

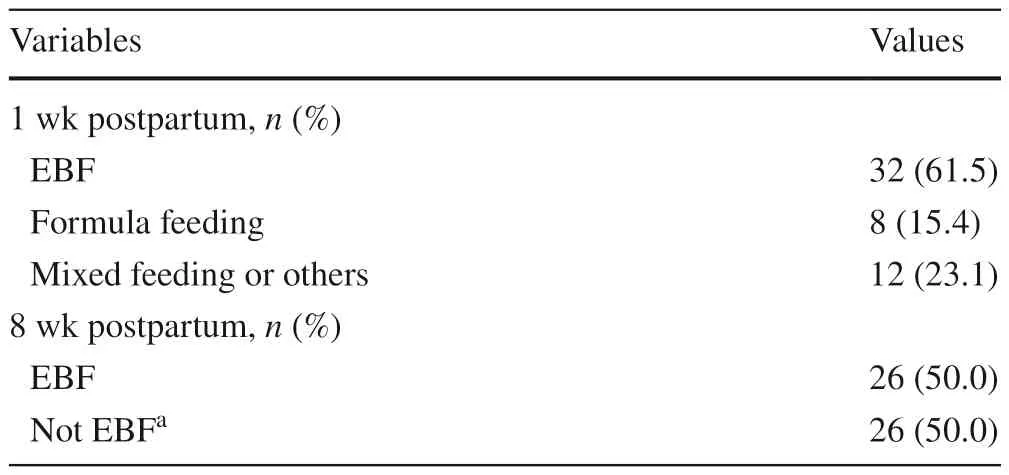

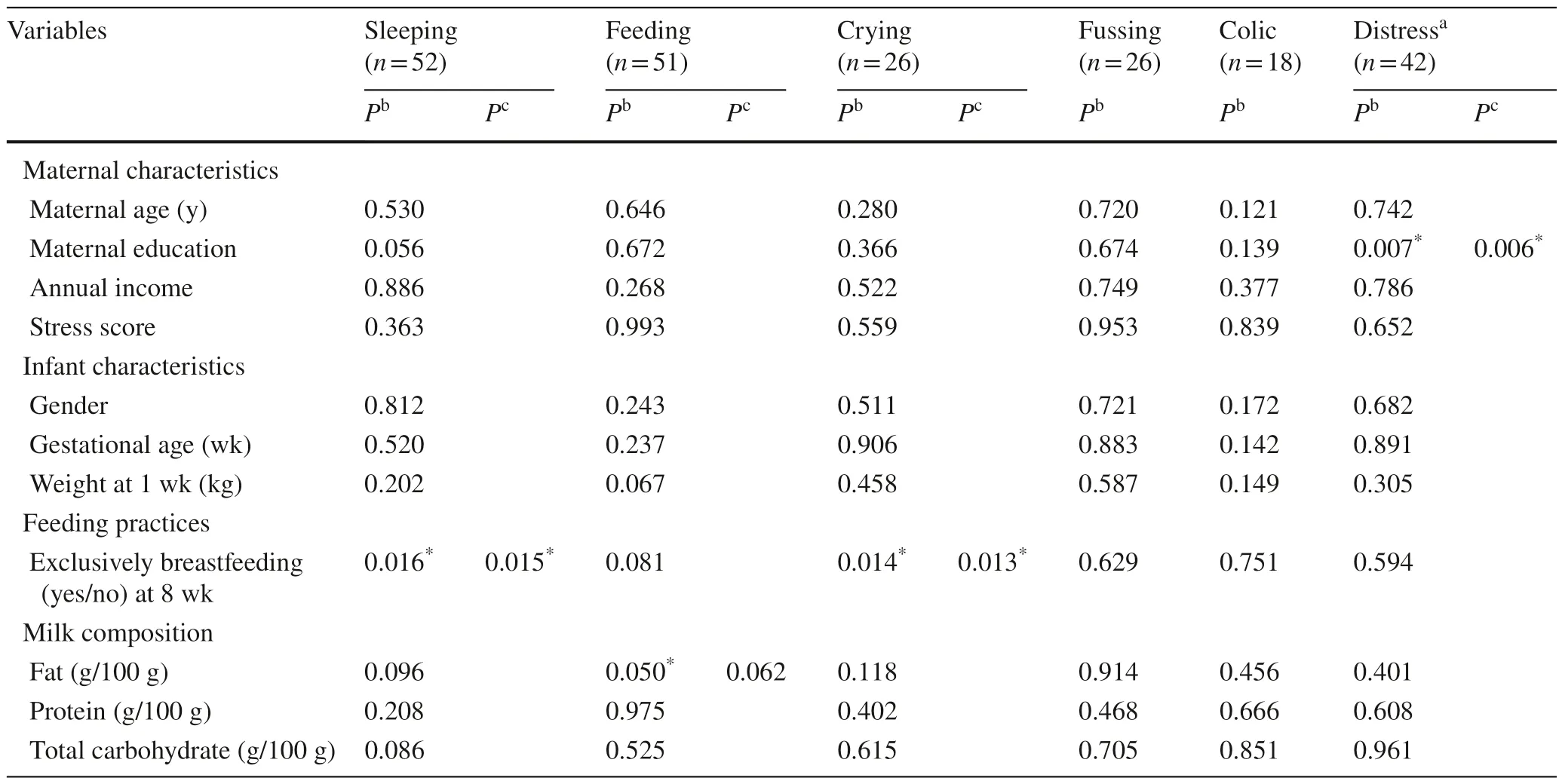

The characteristics of the mothers and infants are displayed in Table 1.As shown in Table 2,only 50% of infants were exclusively breastfed at 8 weeks compared to 61.5% at 1 week.The duration and frequency of five categories of infant behavior are provided in Table 3.Associations of maternal and infant characteristics,feeding practices,and milk composition with infant behavior,including those who reported distress behaviors,are presented in Table 4.

Table 1 Characteristics of the study population

Table 2 Breastfeeding practices among mothers at 1 wk and 8 wk postpartum

Table 4 Associations of predictor variable(s) with infant behavior including those who reported distress behaviors (n is specified)

Predictors of infant sleeping

In univariate analyses,a significant association was observed between EBF and infant sleeping (P=0.02,R2=0.111).EBF infants had a longer sleep duration(859.2±125.8 minutes/day) than non-EBF infants(764.3±146.3 minutes/day).

Predictors of infant feeding duration

In univariate analyses,increased fat content in breastmilk was significantly associated with longer feeding duration at 8 weeks postpartum (P=0.05,R2=0.079).

Predictors of infant distress behaviors

Two sets of univariate analyses were performed for infant distress behaviors: (1) including those who reported the behavior (nis specified) and (2) including all infants (n=52).EBF was significantly associated with infant crying duration (n=26,P=0.01),with anR2 of 0.227.Infants who were not EBF had a longer crying duration (64.5±62.1 minutes/day) than EBF infants(21.4±16.7 minutes/day).Infant colic (n=18) was not significantly associated with any predictor variable (allP>0.05),although infants of mothers with a vocational education (54.0±15.2 minutes/day) reported more infant colic than those of mothers with a bachelor’s degree(19.8±20.6 minutes/day,P=0.007).Infant fussing(n=26) was not significantly associated with any predictor variable (allP>0.05).

Differences in reported infant distress duration (n=42)between the maternal education groups were statistically significant (P=0.007).The distress duration reported by mothers with a vocational education (160.8±32.0 minutes/day) was significantly greater than those with a high school diploma or below (33.3±33.3 minutes/day,P=0.005) and those with a bachelor’s degree (66.4±70.7 minutes/day,P=0.002).

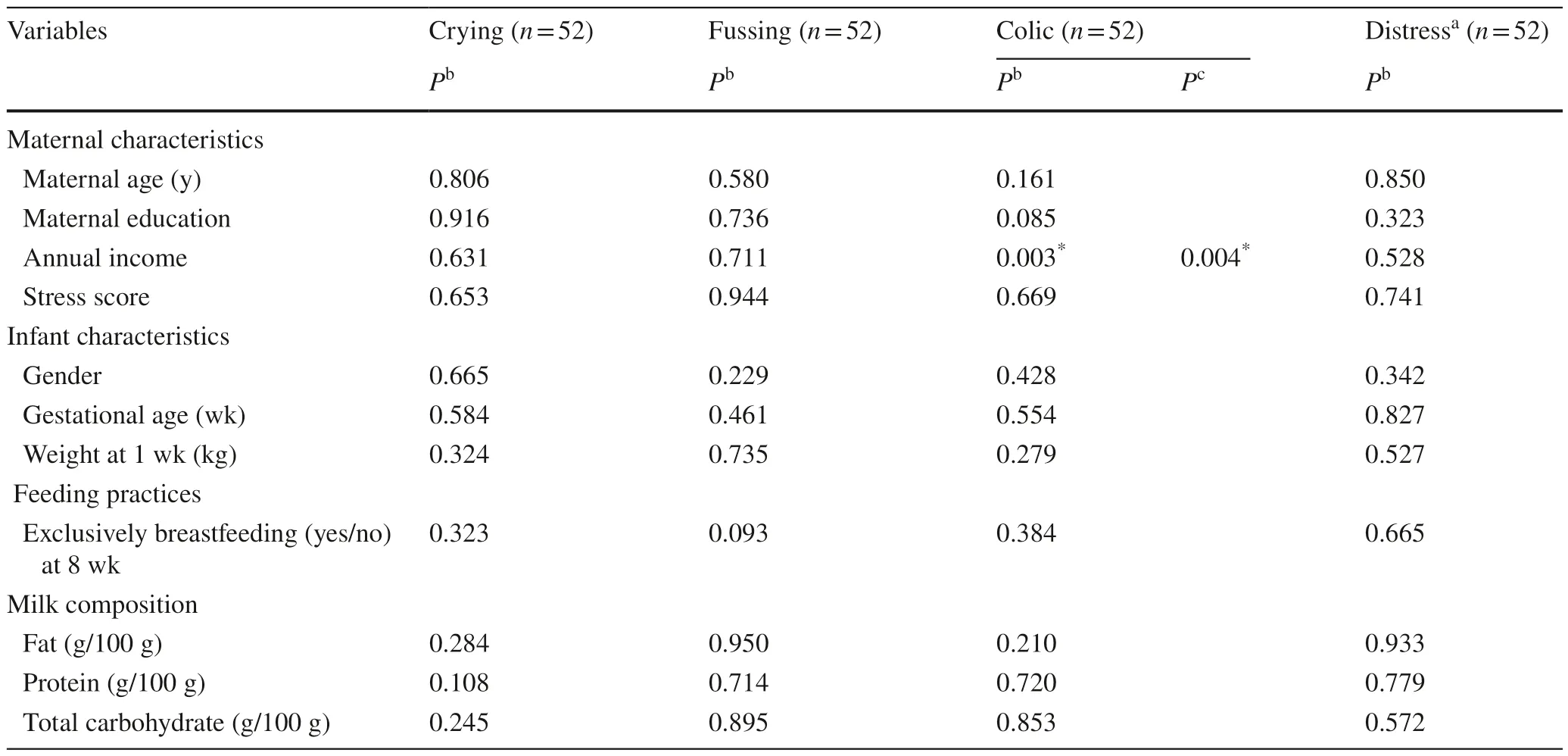

Associations including all infants (n=52) are presented in Table 5.EBF was not associated with crying (P=0.32),and maternal education was not associated with distress(P=0.32).However,in univariate analyses,maternal income was significantly associated with infant colic (P=0.003).Infants of mothers who received more than ¥450,000 per year (36.46±7.55 minutes/day) had significantly greater colic duration than those of mothers who received less than¥200,000 per year (8.24±4.67 minutes/day,P=0.003)and ¥200,000–¥300,000 per year (1.67±5.04 minutes/day,P<0.001).

Table 5 Associations of predictor variable(s) with infant distress behaviors including all infants (n =52)

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the primary analysis showed that infants tended to sleep longer as the breast milk fat content increased(P=0.05).However,after adjusting for the number of recording days,this association was not statistically significant(P=0.06).Nevertheless,consistent with the primary analyses,(1) EBF infants had a longer sleep duration than those not EBF(P=0.02);(2) infants who were not EBF had a longer crying duration than EBF infants (P=0.01);(3) the group of mothers with vocational education reported a significantly greater distress duration (P=0.006);and (4) greater annual household income predicted more reported colic of infants (P=0.004).

Association between infant behavior and growth

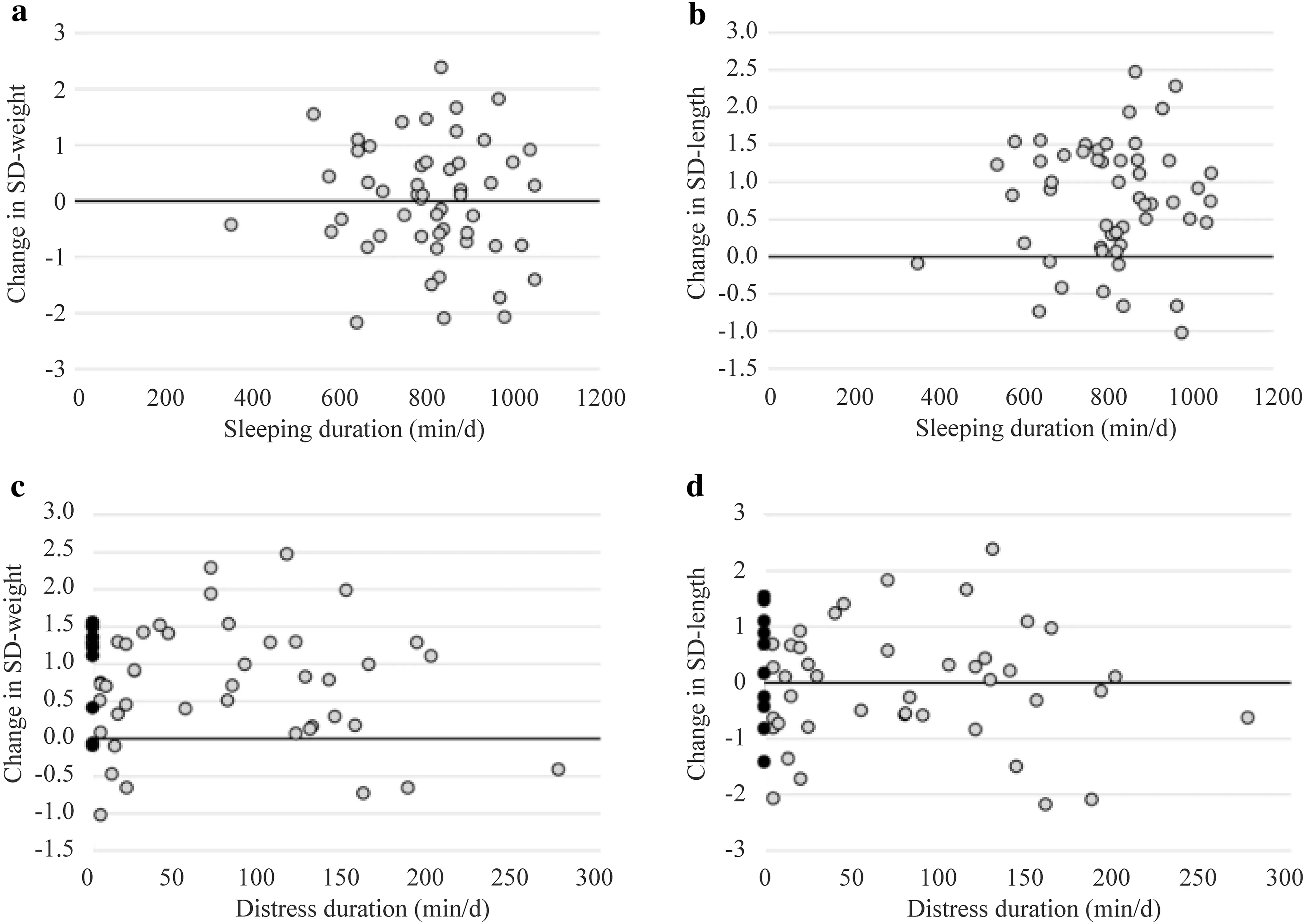

Infant weight gain from 1–8 weeks was not associated with infant sleeping (P=0.96) or infant distress behaviors at 8 weeks,either for those with reported distress behaviors(n=42,P=0.64) or for the whole cohort (n=52,P=0.63).Likewise,infant length gain was not associated with infant sleeping (P=0.54) or infant distress behaviors (P=0.90,P=0.58).Scatter plots showed no apparent trend in the associations (Fig.1).

Fig.1 The association between infant behavior and growth.Scatterplot of sleeping and weight gain (a),sleeping and length gain (b),distress and weight gain (c),distress and length gain (d) at 8 weeks postpartum.The closed circle (filled circle) indicates those who did not report any distress behavior.SD standard deviation

Discussion

This secondary data analysis examined the factors associated with reported infant behavior at 8 weeks postpartum and the association between infant behavior and growth between 1 and 8 weeks in LP and ET infants.The main findings were as follows: (1) EBF was a significant predictor of longer sleep duration and shorter crying duration;(2) mothers with vocational education reported greater distress duration;(3)higher annual income predicted more infant colic;and (4)there was no correlation between infant behavior (sleeping and distress) and growth (weight and length gain).

The positive association between EBF and sleep duration is consistent with some findings from term infants,while the negative association between EBF and crying duration is not consistent with prior studies.Previous research has generally indicated that breastfed infants sleep less and have more night awakenings than formula-fed infants.However,two other studies showed that breastfed infants had shorter sleep episodes (woke more often) but longer total sleep duration at 2–17 weeks of age,and EBF promoted longer nocturnal sleep at 2–4 months postpartum,possibly due to the sleeppromoting compounds (e.g.,melatonin) in breastmilk [11,29].Conflicting results in sleep time between breast-and formula-fed infants may arise from multiple factors,such as the timing of recording,feeding methods,infant sleep environment,maternal perceptions about infant sleeping,and maternal sleep patterns.Interestingly,all mothers included in our study initially intended to exclusively breastfeed for two months,but some in fact did not exclusively breastfeed or continue to exclusively breastfeed as long as planned.This may suggest that “poor” or unexpected infant behavior led women to stop EBF within the first two months.Indeed,longer sleep time among infants may also influence mothers’ feeding decision-making [29].Although our study could not show a causal effect,the results suggest that further research should consider the interaction between EBF and infant behavior,for example,by measuring infant behavior in LP/ET infants who start out with different feeding patterns.On the other hand,in one old study,term infants who were breastfed had longer crying duration than bottle-and mix-fed infants at 3–6 weeks postpartum [29].Premature infants (26–33 weeks) who were breastfed cried almost one hour more than formula-fed infants per day at 4–6 weeks postpartum [30].However,in our study,mothers of EBF infants (n=16) clearly recorded less crying for their infants than mothers of formula-and mix-fed infants.One plausible explanation is that infants with increased crying were more likely to be given infant formula because their mothers had concerns about the adequacy of their breastmilk [31,32],whereas those with less crying were more likely to remain EBF because their mothers believed that breastmilk alone was enough to satisfy their infant.Within this context,it should be noted that mothers’ perception of the frequency and duration of infant crying might be affected by their psychological state,especially when self-reported approaches are used [33,34].Furthermore,infant crying typically reaches a peak around 6 weeks of age and decreases with age [34].It is apparent from previous research that the timings when infant behavior was measured are different and that the association between EBF and crying duration may differ by postnatal age.

In this highly educated sample (over 70% held a bachelor’s degree),the analyses suggested that mothers with a vocational education tended to report greater infant distress duration,which is in partial agreement with previous findings.In many developed countries,lower maternal education and self-esteem were associated with an increased risk of problematic infant crying [17,35].Similarly,lower maternal education was found to be more prevalent among colicky infants at 1.5–2 months of age [36].Vocational education has lower social prestige and status than academic education[37].In addition to low academic performance,individuals with vocational education are more likely to come from families with limited resources,as they tend to relieve the financial burden of the family by entering the labor market early.As a result,mothers with a vocational education in China may suffer more from social problems and pressure than those with an academic degree and therefore be more sensitive to infant distress behaviors.On the other hand,the difference in infant distress duration when comparing vocational education with high school education should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size of high school education (n=3).

Higher maternal income was associated with more reported colic among LP and ET infants,which is in line with some previous studies.Although there is limited supporting evidence,previous studies have suggested that low-income mothers with less social support tend to have difficulty feeding their premature infant,possibly resulting in increased infant colic [17,38].However,in two other studies,a protective effect of EBF on infant colic was reported within the first two months of life [11,39].In other words,EBF can be associated with reduced infant colic.It is hypothesized that higher maternal income was associated with more infant colic,with EBF as a mediator between maternal income and infant colic in the first eight weeks postpartum.Quantitative studies in China indicated that high-income mothers are less likely to maintain EBF because they can afford infant formula or find a paid carer to look after their infant [40].High-income mothers also often work full time in responsible and highly competitive positions,so they have a greater desire to return to work and stop EBF earlier.However,our results are limited by the small sample size for infant colic (n=18) and the timings when infant behavior was measured.Furthermore,the influence of socioeconomic group on infant crying/colic is complex due to the interplay of socio-economic,psychosocial and psychological factors [36].

No significant correlation was detected between infant behavior (sleeping and distress behaviors) and growth(weight and length gain) in LP and ET infants.Although little is known about the association between infant behavior and growth in this group,several studies have recognized bidirectional effects.Some studies have argued that crying may reduce the energy available for infant growth by increasing metabolic rate and decreasing sleep time[10],while others have suggested that infant crying may lead to frequent feeding and consequently weight gain [6].There could thus be two different scenarios.First,crying as a hunger cue could be observed more frequently among LP/ET infants who then grew faster.In other words,rapid growth promotes higher energy intake because infants cry when there is inadequate feeding [8].On the other hand,mothers of premature infants might be more sensitive and report more crying when an infant is not growing well.It is plausible that mothers might have different interpretations of infant hunger cues depending on how their infant grew.As a result,the fact that no association was found in our study could possibly be explained by the fact that the amount of crying reported by mothers was impacted by the growth of infants in opposite directions.Further studies are necessary to verify the bidirectional effects.

This study contributes to the literature on the influence of maternal characteristics on behavior in LP and ET infants and highlights the complex interplay of maternal characteristics,breastfeeding and infant distress behaviors.However,there are several limitations worth noting.First,the sample size of 52 was small,and compliance with completion of diaries was not high.A possible explanation is that mothers were asked to complete several questionnaires and other tasks during the study period.Second,problems arise from the incorrect completion of diaries among these mothers.Although the definitions for the five categories of infant behavior were provided more specifically than those in some studies,it seemed challenging for mothers to distinguish the three infant distress behaviors.Furthermore,it might be argued that maternal perception of infant behavior was measured rather than infant behavior itself.

In conclusion,this study provided support for associations between maternal characteristics,feeding practices,and infant behaviors among LP and ET infants in China.Apart from non-modifiable factors such as maternal education and income,early termination of EBF as a modifiable factor is preventable and manageable.Since China has one of the highest prevalence rates of premature births worldwide every year,it is vital to highlight the challenges faced by mothers of LP/ET infants and the value of EBF.In this regard,high-risk groups such as premature infants from families with low socioeconomic status may benefit from additional lactation support.To address the methodological issues,a larger sample size is needed,and the accuracy of the 3-day infant behavior diary could be improved by educating mothers on infant crying,fussing,or colic and providing more descriptions of each behavior.Alternatively,objective assessments of infant behavior could be adopted together with maternal reports.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the investigators and participants who contributed to this study.

Author contributionsZX identified the research question,established the hypothesis,contributed to the drafting of the study protocol,performed the data analyses,and drafted the manuscript with input from the co-authors.YJ and FM identified the research question,established the hypothesis,contributed to the drafting of the study protocol,and established the study location for recruitment and data collection.WZ established the study location for recruitment and data collection.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThe research was conducted as part of a PhD and expenses were covered from the research group’s funds.All research at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health is made possible by the NIHR Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Center.The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS,the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Data availabilityThe datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approvalEthical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Beijing Children’s Hospital (ID: 2018-167) and University College London (ID: 12681/002).All participants provided written informed consent at recruitment.

Conflict of interestFM receives an unrestricted donation from Philips for research on infant nutrition.All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年10期

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年10期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Instructions for Authors

- Editors

- Information for Readers

- Efficacy of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pediatric hematology/oncology patients: a real-world study

- Human bocavirus 1 and 2 genotype-specific antibodies for rapid antigen testing in pediatric patients with acute respiratory infections

- Real-world performance analysis of a novel computational method in the precision oncology of pediatric tumors