Management of sepsis in a cirrhotic patient admitted to the intensive care unit: A systematic literature review

Nkola Ndomba, Jonathan Soldera

Abstract

Key Words: Sepsis; Septic shock; Cirrhosis; Sequential organ failure assessment score; Mean arterial pressure; Intensive care unit

INTRODUCTION

Physiologically, sepsis is viewed as a proinflammatory and procoagulant response to invading pathogens with three recognized stages in the inflammatory response, with a progressively increased risk of end-organ failure and death[1].Evidence shows that sepsis in cirrhotic patients causes a marked imbalance of cytokine response, known as a "cytokine storm," which converts responses that are normally beneficial for fighting infections into excessive, damaging inflammation.Therefore, the three recognized stages are sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock, and cirrhotic patients are prone to developing sepsis-induced organ failure and death[1].Severe sepsis in cirrhotic patients is associated with high production of proinflammatory cytokines that play a role in the worsening of liver function and development of organ or system failure such as shock, acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, coagulopathy, renal failure, or hepatic encephalopathy[1].Furthermore, cirrhotic patients with severe sepsis can develop sepsis-induced hyperglycemia, defective arginine-vasopressin secretion,adrenal insufficiency, or compartmental syndrome[2].

Sepsis is a severe condition characterized by a deregulation of the body's response to infection and can lead to life-threatening organ dysfunction.As one of the leading causes of admission to intensive care units (ICUs), sepsis has been found to have poorer outcomes in patients with comorbidities such as cirrhosis, as stated in the "Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock"[1-3].Organ dysfunction in sepsis is measured by an increase of two points or more in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, which is associated with a mortality rate greater than 10%[4-5].The SOFA score comprises six sub-scores, including liver failure, which has been found to be associated with higher mortality.The other sub-scores include respiratory, coagulation, cardiovascular, central nervous system, and renal.Each sub-score is rated on a scale of 0 to 4 and summed up to a final score from 0 to 24.Systematic Inflammatory Response Syndrome occurs when two or more criteria, such as body temperature > 38 ℃ or < 36 ℃, tachycardia > 90/min, hyperventilation, and abnormal white blood cell count, are met[2].

Septic shock is a subset of sepsis that leads to profound circulatory and cellular metabolism abnormalities, resulting in substantially increased mortality[4].To identify septic shock, one should look for hypotension that requires vasopressor therapy and a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of less than 65 mmHg despite adequate fluid resuscitation and systolic blood pressure.Additionally, signs of tissue hypoperfusion such as low urinary output, acidosis, and worsening mental status, along with evidence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome, including a body temperature above 38 or below 36 oC,tachycardia, tachypnea, leukocytosis, and documented infection, are also considered[5].

Elevated lactate levels reflect cellular dysfunction in sepsis, and multiple factors contribute to their elevation, including insufficient tissue oxygen delivery, impaired aerobic respiration, acceleration of aerobic glycolysis, and reduced hepatic clearance[1].However, defining sepsis and septic shock poses inherent challenges[3].

The acute change in total SOFA score of more than 2 points due to an infection is identified as organ dysfunction.In patients with a SOFA score of 2 or more, the overall mortality risk is approximately 10%,which is higher than the overall mortality rate of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.This score also identifies a 2-25 fold increased risk of dying compared to patients with a SOFA score less than 2.However, this score is not used as a tool for managing septic patients in the ICU but rather to characterize them clinically.SOFA has greater predictive validity in patients suspected of sepsis in an ICU[3,4].

There are several risk factors associated with sepsis, including patient factors such as immunosuppression, comorbidity, or therapy, microbe factors such as the presence of multi-resistant or virulent bacteria, and procedural risks such as surgery, indwelling catheters, or implantable devices[6].Cirrhosis, which is the end-stage of most chronic liver diseases, has two clinical phases: Compensated and decompensated.The compensated phase is defined as the period between the onset of cirrhosis with minor or no symptoms and the first major complication, while the decompensated phase is when the patient first presents with ascites, variceal hemorrhage, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome.This period is associated with a short survival time.Cirrhosis may be diagnosed by liver biopsy or by signs of chronic liver disease with documented portal hypertension.Cirrhotic patients have a reduced capacity of the reticuloendothelial system to clear bacteria from the gut, resulting in a higher rate of infections and a worse prognosis[7].

Cirrhosis is an irreversible condition caused by several factors or conditions, such as viral hepatitis,alcoholic liver disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.According to the World Health Organization, cirrhosis was the 9th leading cause of death in the west in 2015[8].Studies have shown that mortality among cirrhotic patients with sepsis in the ICU ranges from 18%-66%, with mechanical ventilation being an independent predictor of mortality.The MELD and MELD-Na scores are used for the prediction of 90-day mortality and for organ allocation in liver transplantation.A cohort study by Baudryet al[9] found that mortality of cirrhotic patients with sepsis ranges from 18%-66%.WHO estimates cirrhosis as the 12thcause of mortality in the world, with deaths exceeding 1 million per year.ICUs provide specialized treatment and monitoring for critically ill patients.

The aim of the present paper is to determine the optimal current management of sepsis in cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses(PRISMA-P) protocol[10] and examines published papers on the management of sepsis in cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were cirrhoti c patients over 18 years old, admitted to the ICU with sepsis.The study analyzed the management and prognosis of cirrhotic patients with sepsis, as well as compared the management of sepsis in cirrhotic patients to those without cirrhosis.Only English-language randomized controlled trials (RCTs), retrospective cohort studies, and prospective cohort studies were included.

Outcomes

The analyzed outcomes include survival, length of ICU stay, and the overall prognosis of cirrhotic patients with sepsis admitted to the ICU.

Search strategies

Searches were conducted on PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, and Cochrane databases.Retrieved papers were initially filtered based on their titles and abstracts, and the full text of selected papers were then retrieved and analyzed.Only papers that met the inclusion criteria were included and analyzed.The search strategy is described in Appendix 1 and the critical appraisal of the papers is presented in Appendix 2.

RESULTS

Study selection

Figure 1 illustrates the selection process following the PRISMA-P protocol.Initially, 351 search results were retrieved, out of which 284 were excluded after screening the titles, 46 were excluded after the abstract, and 3 were excluded after full articles.A total of 19 papers met the inclusion criteria and were included for full-text review.The primary outcome of all reviewed papers was the survival of cirrhosis patients with sepsis in the ICU.The review also analyzed the prognostic value of scores such as Child-Turcotte-Pugh, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Sodium(MELD-Na), and SOFA scores for cirrhotic patients with sepsis.The summarized data is available on Table 1 for randomized controlled trials, Table 2 for prospective cohort studies, Table 3 for retrospective cohort studies and Table 4 for selected studies.

Figure 1 PRISMA-P protocol for the systematic review.

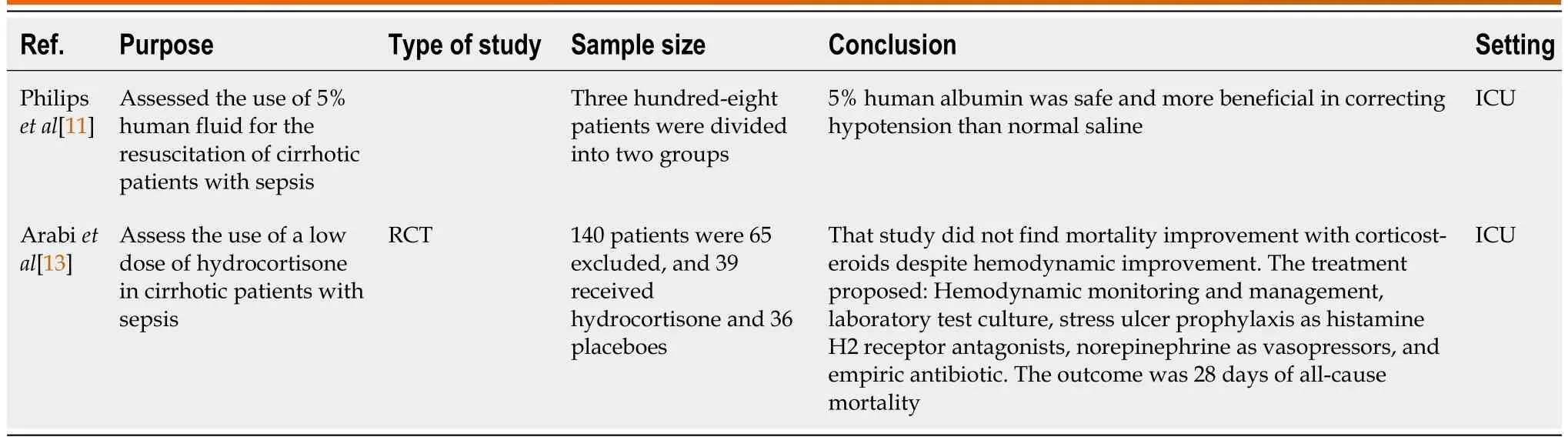

Table 1 Summary of randomized controlled trials

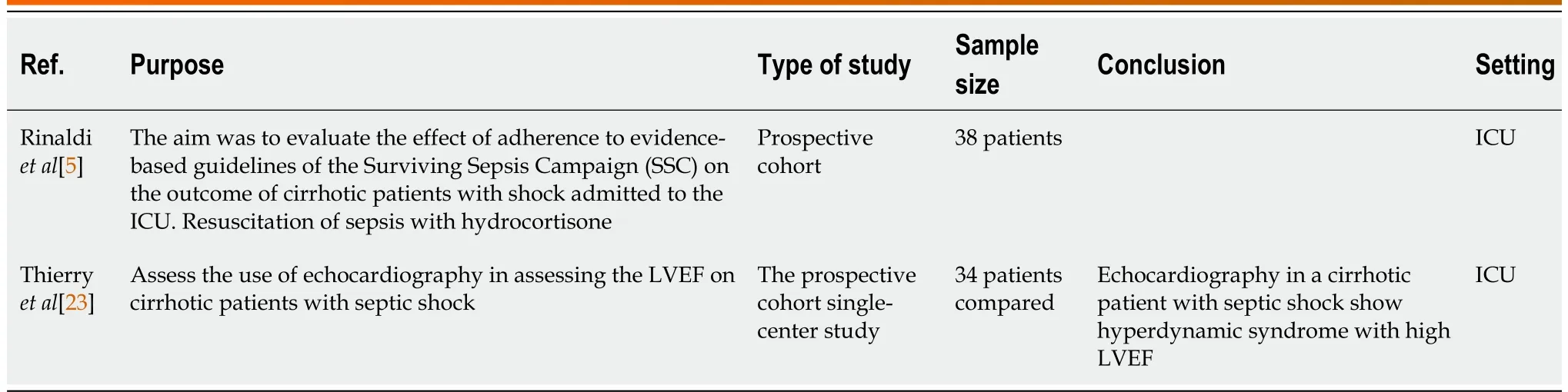

Table 2 Prospective cohort studies

Table 3 Retrospective cohort studies

Table 4 Summary of selected studies

Findings of the review

Albumin:Philipset al[11] found that 5% human albumin corrected hypotension in sepsis with cirrhosis(Table 1).Maimoneet al[12] found that albumin 20% increased MAP above 65 mmHg 3 h after infusion compared to plasmolyte, but with a risk of inducing pulmonary edema (Table 3).

Corticosteroids:Arabiet al[13] concluded that corticosteroids improved the hemodynamic status of the patient but did not change mortality (Table 1).Rinaldiet al[5] and Piccolo Serafimet al[14] found similar results to Arabiet al[13] (Tables 2 and 3).

Infection diagnosis:Villarrealet al[15] concluded that procalcitonin as a biomarker helped with infection diagnosis in cirrhotic patients.Fischeret al[16] found that both presepsin and resistin may be reliable markers of bacterial infection in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and have similar diagnostic performance compared to procalcitonin (Table 3).

Prognosis:Baudryet al[9], Fischeret al[16], Changet al[17], and Sauneufet al[18], found that the prognosis is poor in ICU for cirrhosis patients with sepsis (Table 3).Sassoet al[19] found that mechanically ventilated cirrhotic patients with sepsis have an extremely poor prognosis, and vasopressor use was strongly a predictor of mortality (Table 3).

Vasopressors:Durstet al[20] found that norepinephrine is the best vasopressor to use in cirrhotic patients with sepsis to maintain MAP above 60 mmHg.Umgelteret al[21] concluded that terlipressin is effective as a vasopressor in septic cirrhotic patients in combination with norepinephrine to correct hypotension.Cheblet al[22] recommend starting vasopressors early to avoid aggressive fluid resuscitation and maintain MAP > 65 mmHg (Table 3).

Hyperdynamic syndrome:Thierryet al[23] found that echocardiography helps diagnose hyperdynamic syndrome with high LVEF in septic patients (Table 3).

Mortality: Balet al[24] found 50-day mortality to be about 43.11%.Baudryet al[9] found that the mortality of cirrhotic patients with sepsis ranges from 18%-66%, which is close to the WHO finding that estimates cirrhosis as the 12thcause of mortality in the world, with death exceeding 1 million a year(Table 3).

Scoring system:Chenet al[25] concluded that the qSOFA (Quick SOFA) criteria, consisting of 3 variables, are a better predictor of adverse outcomes associated with sepsis.The presence of two or more abnormalities in patients with suspected infection identifies a higher risk of developing adverse outcomes.

Hemodynamic monitoring:Administer antibiotics within the first hour and monitor physiological parameters like urine output and lactate clearance to prevent end-organ dysfunction[7].In advanced cirrhosis, elevated cardiac index, low systemic vascular resistance, low MAP, and higher central venous oxygen saturation may be present.Lactate levels should be carefully evaluated as they may take a while to lower down to normal levels.Serum lactate measurement is still recommended in these patients[7].Skin mottling score and tissue oxygenation saturation assessed with laser Doppler can also be used as hypoxia of the tissue markers in cirrhosis[7].

Fluid resuscitation:Aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation is recommended in any patient with hypotension or elevated serum lactate.However, the choice of fluid between crystalloid or colloid remains controversial[6,11,12].The SAFE study concluded that albumin improves hemodynamic status and may reduce mortality, while the VISEP study found that pentastarch colloids can cause acute kidney injury in sepsis and increase 90-day mortality[6,11].Human albumin is the fluid of choice in cirrhotic patients with sepsis, as it corrects hypotension more effectively than crystalloid[12].Early goaldirected therapy can help reduce mortality, but the methodology of the Rivers study has been questioned.The recommended fluid should be one that sustains an increase in intravascular volume and contains a chemical composition similar to that of extracellular fluid[6].Hydroxyethyl starch is not recommended in cirrhosis patients as it increases nephrotoxicity, while albumin is associated with dosedependent acute kidney injury[6].An albumin dose of 50-100 g/day is used over crystalloid for initial fluid resuscitation in cirrhosis patients, but no strong evidence exists[6].

Sepsis bundle protocol:According to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) guidelines, the sepsis bundle protocol did not improve survival in cirrhotic patients with sepsis[7].

Vasopressors:Vasopressors are frequently indicated to maintain a MAP of at least 65 mmHg in persistently hypotensive patients.Norepinephrine is widely used in distributive shock for its predominantly alpha-adrenoceptor agonism and vasoconstrictive effect[21].Cirrhotic patients with sepsis and cirrhosis needing vasopressors should have a goal of maintaining the MAP above 60 mmHg.Blood culture and antibiotics should be started as early as possible according to the SCC guidelines[20].SSC international guideline does not recommend vasopressors as monotherapy or the first line for septic shock treatment, and a randomized trial shows the benefit of angiotensin II for refractory vasodilatory shock treatment[7].

Corticosteroids:Corticosteroids are commonly used for unsatisfactory responses to vasopressors.It helps hasten shock resolution, decreases the required dose of vasopressors, and improves the 90-day survival in septic shock patients, and it might increase shock recurrence.Nevertheless, its use in liver cirrhosis remains controversial[7].Hydrocortisone improves the hemodynamic status of the patient without a relevant change in mortality[13,14,18].Hydrocortisone is associated with better shock resolution, although without an impact on survival[5].Low-dose corticosteroid is recommended to be administered early in patients with severe septic shock to patients who are not responding tovasopressors, but this is still controversial[6].

Antibiotics:Broad-spectrum empirical antimicrobial therapy should be commenced early after obtaining blood for culture and microscopy.Many studies have shown mortality improvement when the antibiotic is administered within 1 h of the recognition of sepsis and hypotension[6].The selection of the antimicrobial agents considers antifungal, antiviral, or antiparasitic agents that are directed by the clinical finding, knowledge of the common local pathogens and their antibiotic resistance profiles, and consideration of the patient's potential predisposition to a specific infection, for example, immunosuppression as for Cirrhosis[6].Avoid prolonged therapy with broad-spectrum antimicrobials because it promotes the evolution of resistant organisms, which can lead to the failure of the treatment[6].Sepsis in cirrhotic patients requires a high grade of suspicion so that empiric antibiotics might be started as earlyas possible.Each hour delay in the starting the antimicrobial increases mortality by 1.86 times.Broadspectrum antibiotics should be considered in patients at risk for resistant bacteria[6,7].Early antibiotic start and intravenous administration of albumin 5% or 20% decrease the risk of renal failure development and improve survival in a cirrhotic patient with sepsis[2].

Procalcitonin:Procalcitonin is used as a biomarker for the risk of severe bacterial infection and for stopping antimicrobial therapy, but its role in cirrhotic patients has not been established yet[7].In contrast, Villarrealet al[15] found that procalcitonin might be helpful in identifying bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients.Fischeret al[16] by Fischeret al[16] concludes that both presepsin and resistin are reliable markers of bacterial infection in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis and have similar diagnostic performance to procalcitonin.

Liver transplantation:Liver transplantation is the definitive treatment for cirrhotic patients[7].Cirrhotic patients are prone to bacterial infections and have higher mortality.Early therapeutic management of sepsis in the cirrhotic patient is crucial, and treatment should focus on correcting hypotension and avoiding aggressive fluid resuscitation[22].Echocardiography can help diagnose hyperdynamic syndrome with high LVEF in cirrhotic patients with sepsis.Blood tests and VCS parameters can predict the presence of infection early in cirrhotic patients[23,26].Mottling score and knee score and tissue oxygen saturation measurement six hours after vasopressors have an excellent 14-day mortality prediction[27].Sepsis in cirrhotic patients has a poor outcome compared to sepsis without cirrhosis.Vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, and corticosteroids are suggested treatments, but mortality in 50 days in cirrhosis patients with sepsis was 43%.Mechanically ventilated cirrhotic patients with sepsis have an extremely poor prognosis, and vasopressor use was a predictor of mortality[17,18,19,24].Cirrhotic patients have atypical presentations, and the qSOFA score or CLIF-SOFA score has better predictive ability[25].

Renal-replacement therapy and liver-support system:The use of hemofiltration in patients with sepsis has the potential benefit of alleviating the systemic inflammation of sepsis by removing circulating inflammatory mediators.However, two RCTs did not demonstrate significant reduction in inflammatory mediators nor patients' outcomes.Therefore, hemofiltration should not be recommended for routine management of patients with severe sepsis[1,6].For liver support in the management of cirrhosis, it is recommended to treat the grade of ascites that are grade1 (mild) or grade 2 (moderate)where it is managed out of the ICU with restricted dietary sodium intake, start antidiuretic and monitor urea and electrolyte.For grade 3 that have a large volume of ascites with respiratory implication,paracentesis is recommended followed by dietary sodium restriction and diuretic therapy.Antibiotic prophylaxis should be used to prevent severe sepsis in a cirrhotic patient with ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, or with more than one episode of spontaneous bacterial infection[4].

Glucose control:Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance are common in sepsis, and hyperglycemia may act as a procoagulant, impair neutrophil function, and increase the risk of death.Therefore, it is recommended to monitor and control glucose levels in patients with sepsis[1].

Infection source control:Source control in sepsis involves physical measures for removing the focus of infection.It is essential to identify and manage the source of infection promptly in the ICU[6].

DISCUSSION

The management of sepsis in cirrhosis patients is crucial to decrease the high mortality rate associated with this condition.In recent years, research has aimed to find the most effective therapeutic management for sepsis in cirrhosis patients.Interestingly, current therapeutic strategies for sepsis in cirrhosis patients are similar to the SSC international guidelines accepted for the general population.

Despite current management strategies, mortality remains high in cirrhosis patients with sepsis.Mortality rates are currently around 38%, with 30% of deaths due to infection[28].Liver-specific scores,such as the CLIF-SOFA, CLIF-C Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure (ACLF), and CLIF-C acute decompensation, have been developed to predict mortality in severely decompensated cirrhosis patients[29].

As the cirrhotic liver patient is prone to bacterial infection and impaired immunity status, which triggers complications related to cirrhosis such as hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, variceal bleeding, or hepatorenal syndrome[30-33] that further impaired prognosis[34].The SSC guideline recommends early detection of the source of infection, early initiation of antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, vasopressors, and corticosteroids[11,12].

Several studies have investigated the effectiveness of different therapeutic strategies for sepsis in cirrhosis patients.The use of human albumin 5% and 20% has been found to be beneficial for correcting hypotension and maintaining MAP above 65 instead of crystalloid[11,12].Furthermore, norepinephrine has been found to be the best vasopressor for correcting hypotension in cirrhosis patients with sepsis,and combination therapy with terlipressin and norepinephrine has also been found to be effective[20,22].

One interesting finding is that early vasopressor administration may be more beneficial than aggressive fluid administration in cirrhotic patients with sepsis.Cheblet al[22] found that early use of vasopressors was associated with better outcomes in cirrhosis patients.However, the use of corticosteroids did not show a decrease in mortality in cirrhotic patients with sepsis[9,18,19].

The management of sepsis in cirrhosis patients requires early detection and intervention with antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, vasopressors, and corticosteroids.While current management strategies are similar to those recommended in the SSC international guideline[36], studies have shown that the use of human albumin and norepinephrine or combination therapy with terlipressin and norepinephrine may be more effective.Choudhuryet al[35] found that terlipressin is as effective as noradrenaline in increasing the MAP of more than 65 mmHg at 6 h and 48 h, and has a potential role in treating and preventing variceal bleeding as well as acute kidney injury[36].Despite these efforts, mortality remains high, emphasizing the need for further research in this area to improve outcomes in cirrhosis patients with sepsis[37].

The use of EASL-CLIF criteria on ACLF and CLIF-SOFA for prognostication of sepsis in cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU has gained significant attention[8,38].These scoring systems have been developed to assess the severity of liver disease and predict mortality in severely decompensated cirrhosis patients[39-42].By incorporating organ failure parameters, such as cardiovascular, renal,respiratory, neurological, hematological, and hepatic dysfunction, these criteria provide a comprehensive evaluation of the patient's condition.In the context of sepsis, the EASL-CLIF criteria can help identify cirrhotic patients at higher risk of poor outcomes and guide clinicians in making informed decisions regarding treatment strategies and resource allocation[8,38].The CLIF-SOFA score, in particular, has shown promise in predicting short-term mortality and facilitating risk stratification in this vulnerable population[29,43-45].By utilizing these criteria, healthcare professionals can enhance their ability to prognosticate sepsis in cirrhotic patients, thereby improving patient care and potentially reducing mortality rates.Further research and validation studies are warranted to optimize the use of EASL-CLIF criteria for prognostication and guide personalized interventions in this challenging clinical scenario[8,38].

The studies included in this systematic review provide valuable insights into the management of sepsis in patients with cirrhosis.However, these studies also have several limitations that need to be acknowledged.One of the major limitations of these studies is the absence of complete guidelines on the management of sepsis in patients with cirrhosis[37].Although different therapeutic steps were proposed, these studies do not provide a comprehensive guide for managing these patients.

小舞臺 大亮點(diǎn)(李風(fēng)) ..................................................................................................................................7-42

Moreover, most of the studies included in this systematic review were RCTs and cohort prospective and retrospective studies.While these studies provide strong and moderate evidence, they also have limitations in terms of generalizability.This is because most of these studies were conducted on single centers with small sample sizes.For instance, studies by Rinaldiet al[5], Philipset al[11], Maimoneet al[12], Arabiet al[13], Sauneufet al[18], Durstet al[20], Thierryet al[23] Balet al[24], Chenet al[25], Galboiset al[27] were conducted on small sample sizes, which limits the generalizability of their findings.

Furthermore, the prospective nature of some studies can also affect the results due to missing information.For example, studies by Rinaldiet al[5], Baudryet al[9], Philipset al[11], Maimoneet al[12],Arabiet al[13], Serafimet al[14], Changet al[17], Sauneufet al[18] Sassoet al[19] Durstet al[20], Cheblet al[22], Thierryet al[23], Balet al[24], and Chenet al[25], and Galboiset al[27] were conducted prospectively and some information was missing, which can affect the accuracy of the results.

Moreover, retrospective studies have their limitations as well, as not all information was present.For instance, Rinaldiet al[5], Baudryet al[9], Philipset al[11], Maimoneet al[12], Arabiet al[13], Serafimet al[14], Villarrealet al[15], Fischeret al[16] Changet al[17], Sauneufet al[18], Durstet al[20], Umgelteret al[21] Cheblet al[22], Thierryet al[23], Balet al[24], Chenet al[25], Guoet al[26] and Galboiset al[27], all suffered from selection bias and missing information bias.

In addition, it is important to acknowledge that this review has certain limitations.Although we made efforts to gather relevant sources, we were unable to conduct an exhaustive search, leading to some sources remaining unexplored.This constraint resulted from the time limitations imposed during the review process.Consequently, the review may not encompass the full breadth and depth of available literature on the management of cirrhosis patients with sepsis admitted to the ICU.Furthermore, it is worth noting that a substantial proportion of the included research papers were retrospective studies with occasional missing information.To enhance the understanding and enhance outcomes in cirrhotic patients with sepsis, further research endeavors are warranted.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, sepsis in cirrhotic patients is a complex and challenging clinical scenario.Our systematic review of the literature revealed that there is no standardized approach to the management of sepsis in cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU.Although there is evidence to support early identification of infection, prompt administration of antibiotics, and aggressive resuscitation with fluids and vasopressors, the optimal management of these patients remains unclear.Furthermore, the studies included in this review were limited by small sample sizes, single-center designs, and missing data,highlighting the need for larger, multicenter trials to establish best practices for managing sepsis in cirrhotic patients.

Despite these limitations, our review suggests that using prognostic scores such as SOFA, MELD, and MELD-Na can help identify high-risk patients and guide clinical decision-making.Furthermore,improving outcomes in septic cirrhotic patients will require a multidisciplinary approach, including collaboration between intensivists, hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, and other healthcare providers.With the growing burden of cirrhosis and sepsis worldwide, further research is urgently needed to clarify the optimal management of this complex patient population and improve outcomes for these critically ill patients.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research results

The study conducted a systematic review to investigate the management of sepsis in cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU.The researchers selected 19 papers that met the inclusion criteria, focusing on survival and prognostic factors for this patient population.The findings indicated that albumin administration corrected hypotension in sepsis with cirrhosis, while corticosteroids improved hemodynamic status without affecting mortality.Procalcitonin was found to be helpful in diagnosing bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients, and vasopressors such as norepinephrine and terlipressin were recommended to maintain mean arterial pressure above specific thresholds.The prognosis was generally poor for cirrhotic patients with sepsis, especially for mechanically ventilated patients or those requiring vasopressors.The use of fluid resuscitation, particularly with human albumin, was recommended, and early antibiotic administration within the first hour showed improved outcomes.The qSOFA criteria were identified as a better predictor of adverse outcomes in sepsis, and echocardiography aided in diagnosing hyperdynamic syndrome.Liver transplantation was highlighted as the definitive treatment for cirrhotic patients.The study also mentioned the potential benefits and limitations of renal replacement therapy and liver support systems in sepsis management.Source control and glucose control were emphasized as essential aspects of sepsis management.

Research conclusions

The study proposes that the current therapeutic strategies for sepsis in cirrhosis patients, which are similar to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for the general population, may not be sufficient in reducing mortality rates in this specific patient group.It highlights the need for further research and development of comprehensive management guidelines for sepsis in cirrhosis patients.The study suggests that the use of human albumin and norepinephrine, as well as combination therapy with terlipressin and norepinephrine, may be effective in correcting hypotension and improving outcomes in cirrhosis patients with sepsis.Additionally, it indicates that early administration of vasopressors could be more beneficial than aggressive fluid administration in this patient population.However, the use of corticosteroids did not show a decrease in mortality.

Research perspectives

Future research should focus on developing standardized management guidelines specifically tailored for sepsis in cirrhosis patients.These guidelines should encompass early detection of infection,appropriate antibiotic therapy, fluid resuscitation, vasopressor selection, and corticosteroid use.There is a need for larger, multicenter trials to validate the findings of existing studies and establish best practices for managing sepsis in cirrhosis patients.These studies should have larger sample sizes and address the limitations of previous research, such as single-center designs and missing data.Prognostic scores, such as SOFA, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), and MELD-Na, should be further evaluated and incorporated into the management of sepsis in cirrhosis patients to identify high-risk individuals and guide treatment decisions.A multidisciplinary approach involving intensivists, hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, and other healthcare providers is essential for improving outcomes in septic cirrhotic patients.Collaboration and coordination among these specialties should be emphasized in future research and clinical practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the Acute Medicine MSc program at the University of South Wales for their invaluable assistance in our work.We acknowledge and commend the University of South Wales for their commitment to providing advanced problem-solving skills and lifelong learning opportunities for healthcare professionals.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Both authors contributed to writing and reviewing the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement:The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial.See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:United Kingdom

ORCID number:Jonathan Soldera 0000-0001-6055-4783.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies:Federa??o Brasileira De Gastroenterologia; Sociedade

Brasileira de Hepatologia.

S-Editor:Ma YJ

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Cai YX

World Journal of Hepatology2023年6期

World Journal of Hepatology2023年6期

- World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Liver injury from direct oral anticoagulants

- Randomized intervention and outpatient follow-up lowers 30-d readmissions for patients with hepatic encephalopathy, decompensated cirrhosis

- Lower alanine aminotransferase levels are associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver patients

- Acute pancreatitis in liver transplant hospitalizations: Identifying national trends, clinical outcomes and healthcare burden in the United States

- Role of vascular endothelial growth factor B in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its potential value

- Tumor budding as a potential prognostic marker in determining the behavior of primary liver cancers