Changes in grain-filling characteristics of single-cross maize hybrids released in China from 1964 to 2014

GAO Xing ,Ll Yong-xiang ,YANG Ming-tao,Ll Chun-hui,SONG Yan-chun,WANG Tian-yu,Ll Yu ,SHl Yun-su

Institute of Crop Sciences,Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences,Beijing 100081,P.R.China

Abstract Grain filling is the physiological process for determining the obtainment of yield in cereal crops. The grain-filling characteristics of 50 maize brand hybrids released from 1964 to 2014 in China were assayed across multiple environments.We found that the grain-filling duration (54.46%) and rate (43.40%) at the effective grain-filling phase greatly contributed to the final performance parameter of 100-kernel weight (HKW). Meanwhile,along with the significant increase in HKW,the accumulated growing degree days (GDDs) for the actual grain-filling period duration (AFPD) among the selected brand hybrids released from the 1960s to the 2010s in China had a decadal increase of 23.41°C d. However,there was a decadal increase of only 19.76°C d for GDDs of the days from sowing to physiological maturity (DPM),which was also demonstrated by a continuous decrease in the ratio between the days from sowing to silking (DS) and DPM (i.e.,from 53.24% in the 1960s to 49.78% in the 2010s). In contrast,there were no significant changes in grain-filling rate along with the release years of the selected hybrids. Moreover,the stability of grain-filling characteristics across environments also significantly increased along with the hybrid release years. We also found that the exotic hybrids showed a longer grain-filling duration at the effective grain-filling phase and more stability of the grain-filling characteristics than those of the Chinese local hybrids. According to the results of this study,it is expected that the relatively longer grain-filling duration,shorter DS,higher grain-filling rate,and steady grain-filling characteristics would contribute to the yield improvement of maize hybrids in the future.

Keywords: maize (Zea mays L.),grain-filling rate,grain-filling duration,stability

1.lntroduction

As one of the main cereal crops worldwide,maize (Zea maysL.) plays an important role in meeting human needs. It is expected that by 2050,the world’s major food production will need to double to meet the basic needs of mankind,and maize would contribute 45% to the global food demand (Hubertet al.2010). As such,high yield is still one of the primary goals for maize breeding.

Maize yield had increased greatly with the extension of single-cross hybrids throughout the world (Cardwell 1982;Tollenaar 1989;Russell 1991;Duvick 1992;Eyherabide and Damilano 2001;Duvicket al.2004;Luqueet al.2006;Mitrovi?et al.2016;Qinet al.2016). It was believed that more than half of the yield increase was contributed by the improvements in genetic gain (Duvick 2005),which were reflected by regular changes in yield-related and morphological traits (Duvicket al.1997;Liet al.2011;Wanget al.2011). In any case,the continuous yield increase means an increase in grain dry matter,which is directly determined by the physiological process of grain filling. Therefore,a retrospective analysis of grainfilling characteristics would provide valuable clues for the development of new breeding strategies and agronomic practices to increase productivity.

In the United States (U.S.),a significant increase was observed in the grain-filling duration with the release eras of maize hybrids,but not in the grain-filling rate (Cavalieri and Smith 1984). However,different results were obtained when using different Chinese representative hybrids.For example,by using a set of 20 hybrids released from the 1960s to the 2010s,Ding (2012) found that modern Chinese hybrids had both faster grain-filling rate and longer grain-filling duration than the older hybrids. However,Liuet al.(2015) indicated that only faster grain-filling rates were detected for modern hybrids compared to the older hybrids in another set of 14 Chinese single-cross hybrids.

At least three stages have occurred since the utilization of single-cross hybrids began in the 1960s in China (Dai 2000). Since the end of the 1990s,with the opening of the seed market,international seed companies have set up local experiment stations in China,and thus,a series of competitive hybrids were released,greatly contributing to local maize production. With the introduction of new breeding strategies and resources,a new cycle of variety improvements is inevitable.

Therefore,a set of representative single-cross maize hybrids released by both Chinese local breeders and Pioneer,an international seed company,were selected for this study. The grain-filling characteristics of these brand hybrids were assayed across multiple environments. The objectives were: (i) to examine the contributions of grainfilling characteristics to the genetic gain of grain weight,(ii) to clarify changes in grain-filling characteristics for the selected brand single-cross hybrids released in China from the 1960s to the 2010s,and (iii) to compare the grain-filling characteristics between local and exotic hybrids released since 2000 in China.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Plant materials and experiment design

According to the data query (http://202.127.42.145/bigdataNew/) and the feedback from breeders,a set of 50 hybrids was carefully selected to represent the singlecross maize hybrids that were widely grown in China from 1964 to 2014. They included 32 hybrids released by Chinese local breeders and 18 brand hybrids released by Pioneer Company in China since 2002 (Appendix A).Among the 32 Chinese local single-cross hybrids,23 were used to study the changes in agronomic traits,including yield related traits (Liet al.2011,2014;Wanget al.2011).

Grain-filling characteristics were identified with one replication in four environments. Three environments were located at the “spring corn” area of China,i.e.,Changping in Beijing (40°10′N,116°13′E) in 2014(14CP) and 2015 (15CP) and Shunyi in Beijing (40°13′N,116°35′E) in 2015 (15SY),where the hybrids were sown on 10 May,5 May and 8 May,respectively. The fourth environment was located at the “summer corn” area of China,i.e.,Xinxiang of Henan Province (35°05′N,113°42′E) in 2016 (16XX). Beijing is located in the transition zone between the spring corn area and the summer corn area in China,where most maize hybrids can grow well. Xinxiang is located in the northern area of the Huang-Huai-Hai region of China,and it also has a mild environment for the growth of most of maize hybrids.Each hybrid was sown in an individual 3-m long plot with 6 rows established 0.6 m apart. Plots were thinned at the third leaf (V3) stage to a plant density of 6 plants m-2. The experiments were conducted under no water stress,and weeds and pests were regularly controlled.

Daily maximum and minimum temperatures were collected from the weather stations at the research farms and were used to calculate growing degree days(GDDs) from sowing to silking and GDDs from sowing to physiological maturity (Appendix B). A high base of 30°C and a low base of 10°C was applied to the temperature data from a nearby weather station to obtain an effective high (TH) and low (TL) for each day. Daily maximum and minimum temperatures between the base temperatures were used unchanged as TH and TL. Maxima above the high base were adjusted as TH=30-(Maximum-30)and minima below the low base were entered as TL=10.Finally,the daily GDD=(TH+TL)/2-10 (Cross 1975).

2.2.Plant sampling and measurements

In each experiment,the date of silking for each hybrid was recorded when silks emerged from 50% of the plants in a plot,and the GDD for the days to silking(DS) for each hybrid was calculated as the accumulated GDDs during the period from sowing to the date of silking. Similarly,the date of physiological maturity for each hybrid was recorded when the milk line for half of the sampled kernels from the middle of an ear disappeared and the black layer appeared,and the GDD for the days to physiological maturity (DPM) for each hybrid was calculated as the accumulated GDDs during the period from sowing to the date of black layer emergence. Meanwhile,the actual grain-filling period duration (AFPD) was calculated as the accumulated GDDs during the period from silking to physiological maturity. To estimate the relative proportion of grainfilling duration within the whole growth period,the ratio of DS to DPM (DS/DPM) and the ratio of AFPD to DPM(AFPD/DPM) were calculated according to the mean values of each of the traits across the four environments.

To eliminate the effect of the non-uniform silking date within each plot,plants silking on the same day were marked and used for the measurements as follows:three ears for each hybrid were hand-collected at 10,14,21,and 28 days after silking and then every 3 days until physiological maturity. For each sampled ear,approximately 100-150 kernels in the middle part were threshed and dried to constant weight in a forced airoven at 75°C for 72 h. The kernel number and dry weight of each sample were recorded and used to calculate the 100-kernel weight (HKW) as the average of three ears at each sampling time for each hybrid.

2.3.Calculation of grain-filling parameters using the Richards model

Generally,the process of grain-filling was divided into three stages,i.e.,the lag phase,the effective grainfilling phase and the maturation drying phase (Bewley and Black 1985). Therefore,the fitting of the grainfilling process for each hybrid was performed using the Richards Model (W=A/(1+Be-Kt)1/N,where W is the grain weight,A is the final grain weight,t is GDD at a given sampling day,e is the Euler number,and B,K,and N are coefficients in the regression equation in Curve Expert 1.4 (Richards 1959;Zhuet al.1988;Yanget al.2001).Then,according to the fitted model,the mean grain-filling rate on each sampling day for each hybrid was calculated by the following equation: G=AKBe-Kt/(N(1+Be-Kt)(N+1)/N).Meanwhile,two inflection points of the grain-filling rate equation,t1=-ln((N2+3N+N(N2+6N+5)1/2)/2B)/K and t2=-ln((N2+3N-N(N2+6N+5)1/2)/2B)/K,and the point at physiological maturity (t3) were used to divide the whole grain-filling process into three phases (Appendix C). The HKW at the two inflection points can be calculated by w1=A/(1+Be-Kt1)1/Nand w2=A/(1+Be-Kt2)1/N. Finally,the accumulated dry matter (W1=w1,W2=w2-w1,W3=Aw2),grain-filling duration (T1=t1,T2=t2-t1,T3=AFPD-t2)and grain-filling rate (G1=W1/T1,G2=W2/T2,G3=W3/T3) at each of the three different grain-filling phases were also calculated according to the fitted model (Zhu 1988).

2.4.Statistical analysis

Correlations among the grain-filling characteristics and the growth period-related traits,as well as the HKW at physiological maturity,were calculated using the mean values across all four environments for all of the selected hybrids. According to previous studies,the performance of HKW showed a continuous increase with the release year of maize hybrids (Duvicket al.1997;Liet al.2011;Wanget al.2011),which could be considered as a very good indicator for the yield improvement of maize hybrids. Therefore,the contributions of grainfilling duration and grain-filling rate at different phases to the final HKW were estimated using the mean values across all four environments with a stepwise regression model. The changes in grain-filling characteristics were estimated by simple fixed-effect regressions of the grainfilling-related traits against hybrid release year using the mean values across the four environments. Meanwhile,to evaluate the stability of grain-filling characteristics for the selected hybrids,the coefficient of variation(CV) of each grain filling-related trait was calculated as CV (%)=SD/Mean,where SD and mean refer to the standard deviation and mean of the values of the grainfilling-related trait across all environments for each hybrid. Phenotypic correlations (Proc CORR),stepwise regression (Proc REG/STEPWISE),multiple comparison analysis (Proc GLM/DUNCAN,α=0.05),andt-tests (Proc TTEST) were conducted using the SAS Software (SAS Institute 2009).

3.Results

3.1.Contributions of grain-filling characteristics to grain weight

The phenotypic distributions and correlations of the grainfilling characteristics and HKW in all 50 assayed singlecross hybrids are shown in Appendix D. Except for G1,T1and T3,significantly positive correlations were observed between the final HKW at physiological maturity and the grain-filling traits at the effective grain-filling phase and the maturation drying phase (G2,r=0.49;G3,r=0.59;T2,r=0.66). Moreover,DS was positively correlated with G2(r=0.44) and T1(r=0.39),but negatively correlated with T3(r=-0.29). DMP was significantly correlated with the HKW (r=0.54) and positively correlated with the grainfilling durations of T2(r=0.42) and T3(r=0.39). Similarly,AFPD was significantly correlated with the HKW (r=0.54),T2(r=0.70) and T3(r=0.73). Therefore,the prolonging of AFPD and DPM strongly benefits the improved grainfilling duration and the increased HKW.

The contributions of grain-filling characteristics to the final HKW at maturity were analysed using the module of Proc REG/STEPWISE in SAS (SAS Institute 2009),and the final regression equation was obtained:HKW=0.009T1+0.102T2+505.918G2-33.262. In this equation,the contributions of G2,T2and T1to HKW were significant at the 0.05 probability level,and they explained 43.40,54.46,and 0.24% of the phenotypic variation in HKW,respectively. It should be noted that the majority of the phenotypic variation was explained by the grainfilling duration (T2) and rate (G2) at the effective grainfilling phase. In addition,an average of 47.52% of the accumulated dry matter for kernels was obtained at this phase,suggesting its importance for the formation of grain yield.

3.2.Changes in grain-filling characteristics

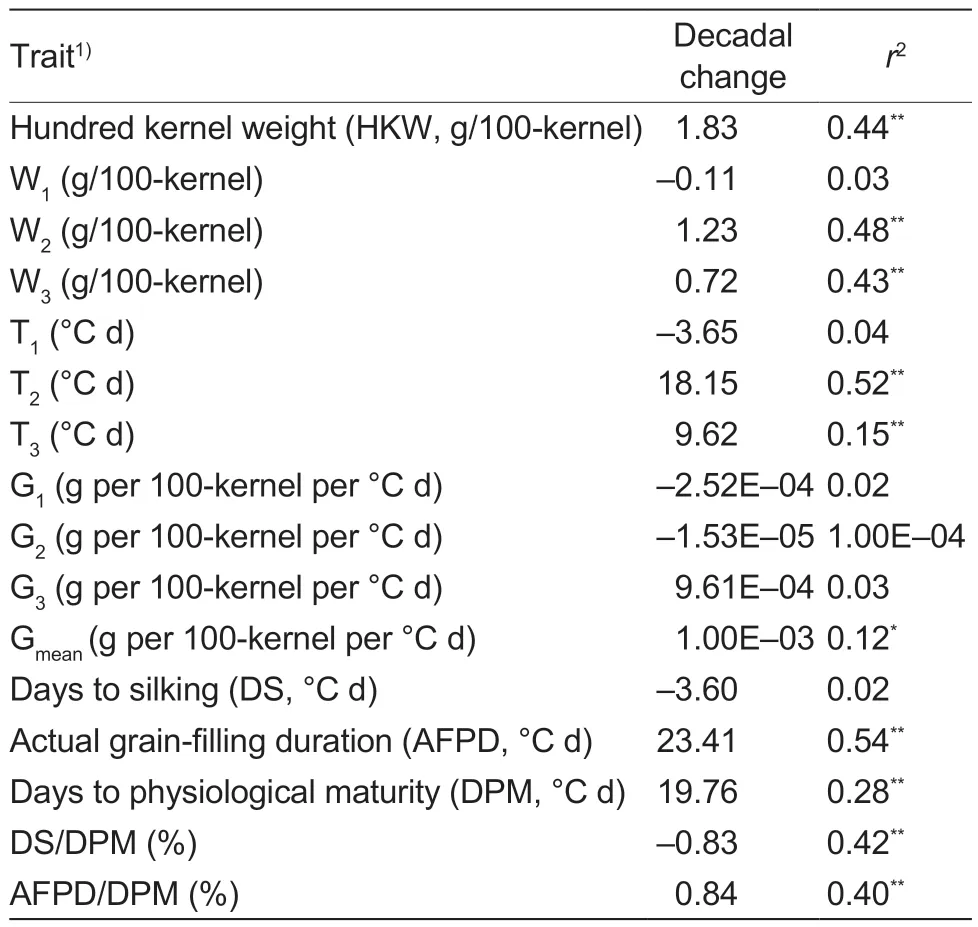

Changes in grain-filling characteristics at the three phases were estimated for each environment and across the four environments (i.e.,mean values) by the regressions with the hybrid release year. Meanwhile,the genetic gains of HKW,DS,DPM,AFPD,DS/DPM (%),and AFPD/DPM (%)were also estimated using the mean values across the four environments by simple regressions with the hybrid release year (Table 1).

Table 1 Regression analysis of traits related to grain-filling characteristics on year of release for 50 single-cross hybrids

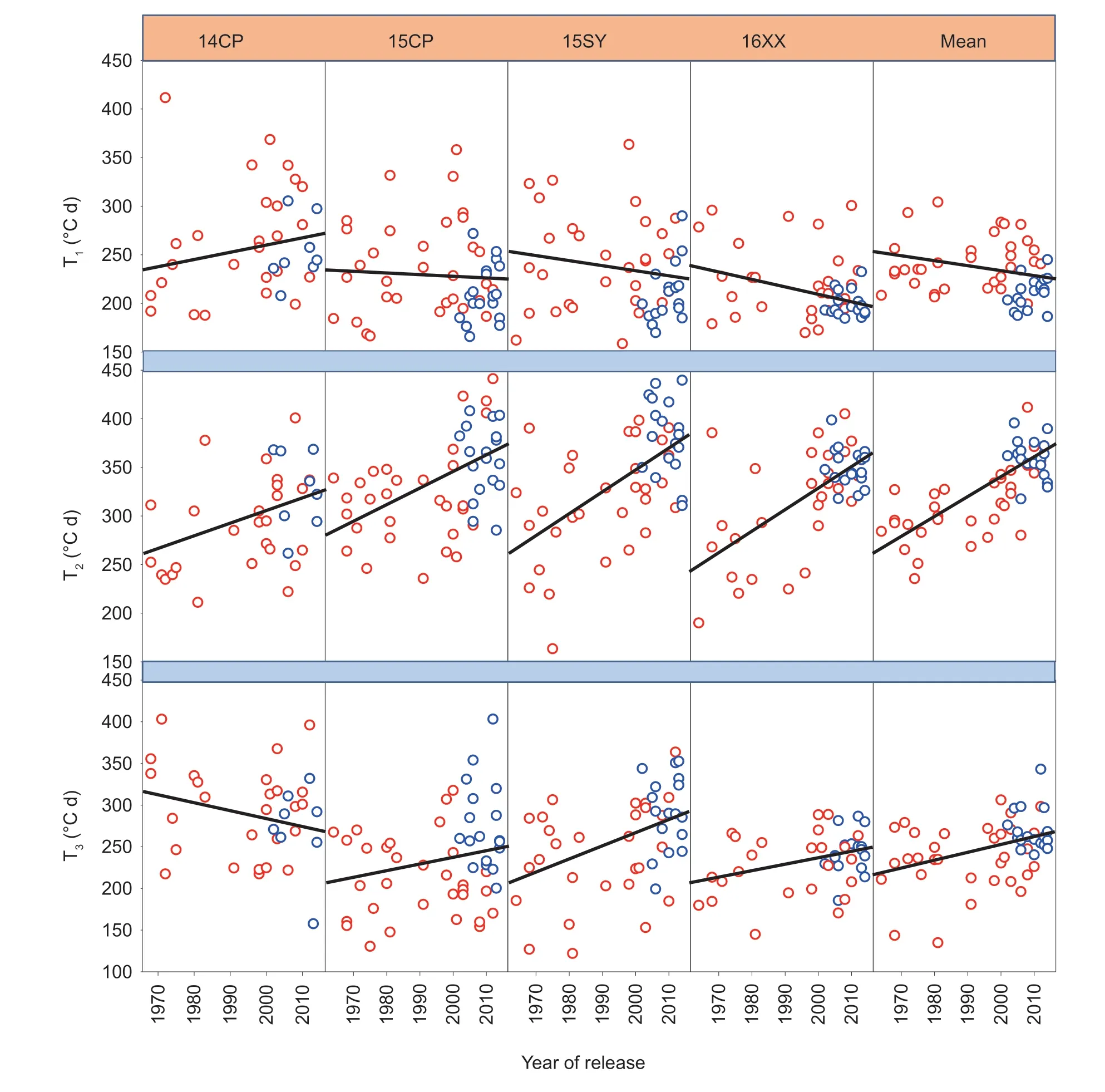

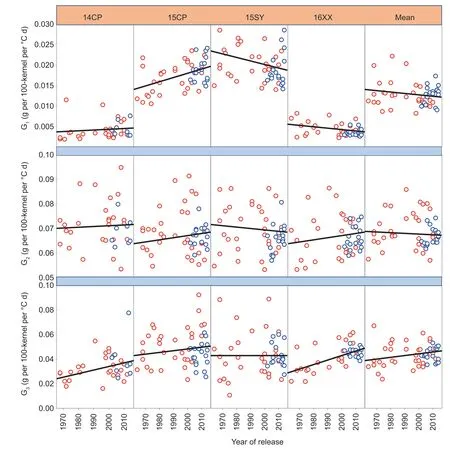

With the improvement of HKW,significant genetic gains were observed for the accumulated dry matter at the effective grain-filling phase (W2,r2=0.48) and the maturation drying phase (W3,r2=0.43) but not at the lag phase (Appendices E and F). Significant genetic gains were also detected for grain-filling duration at the effective grain-filling phase (T2,r2=0.52) and the maturation drying phase (T3,r2=0.15) (Fig.1). However,there were no significant changes in the grain-filling rates across all four environments at any of the phases (Fig.2). As such,to a large extent,the improvement of HKW is attributed to the increase in grain-filling duration for these selected maize single-cross hybrids released during the 1960s to the 2010s in China.

Fig.1 Simple linear regressions of grain-filling duration (T1,T2 and T3) at different grain-filling phases in the year for maize hybrids released across the four environments. CP,Changping in Beijing;SY,Shunyi in Beijing;XX,Xinxiang in Henan Province. T1,grain-filling duration in the lag phase;T2,grain-filling duration in the effective grain filling phase;T3,grain-filling duration in the maturation drying phase.

Fig.2 Simple linear regressions of grain-filling rates (G1,G2 and G3) at different grain-filling phases in the year for maize hybrids released across the four environments. CP,Changping in Beijing;SY,Shunyi in Beijing;XX,Xinxiang in Henan Province. G1,mean grain-filling rate in the lag phase;G2,mean grain-filling rate in the effective grain-filling phase;G3,mean grain-filling rate in the maturation drying phase.

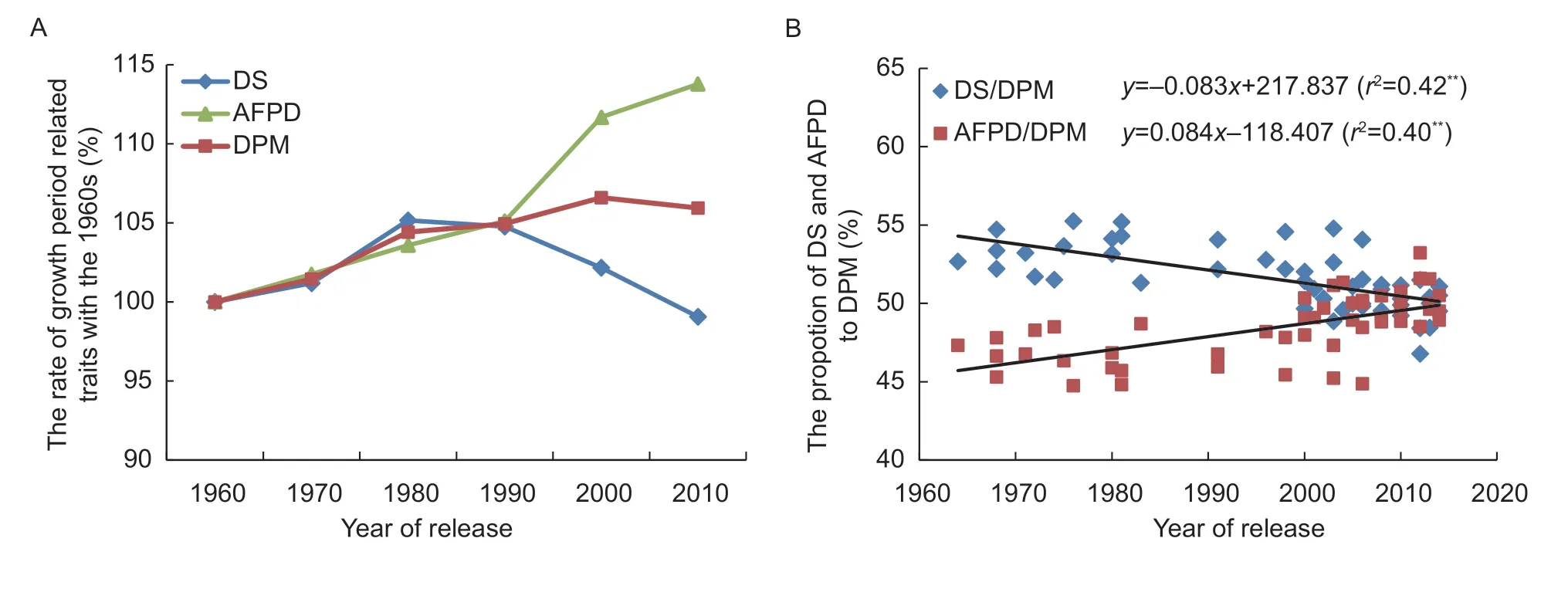

Significant correlations were observed between grainfilling characteristics and growth period-related traits(Appendix D),especially between the DPM and the grainfilling duration characteristics. Therefore,the changes in growth period-related traits were also analysed by the decadal changes of the released hybrids (Fig.3-A;Appendix G). This analysis indicated that,compared with the single-cross hybrids in the 1960s (with average accumulated GDD of 849.51°C d),DS gradually increaseduntil the 1980s (with average accumulated GDD of 893.28°C d),but it then decreased after the 1990s (with average accumulated GDD of 889.99°C d in the 1990s;867.90°C d in the 2000s;and 841.54°C d in the 2010s).Meanwhile,DPM gradually increased until the 2000s but decreased in the 2010s. Interestingly,the AFPD increased continuously from the 1960s (746.34°C d)to the 2010s (849.21°C d). It should also be noted that with the decrease in DS/DPM,the ratio of AFDP/DPM in each decade increased continuously from the 1960s to the 2010s (from the average value of 46.76% in the 1960s to 50.22% in the 2010s) (Fig.3-B;Appendix G).Thus,it seems reasonable to speculate that the earlier silk appearance directly increased the period of AFPD and then indirectly contributed to the prolonged grain-filling duration.

Fig.3 Changes in growth period traits for maize hybrids released in different eras. A,changes in growth period traits between different eras compared to the reference value,which was defined by the trait value in the 1960s. DS,days from sowing to silking;AFPD,days from silking to physiological maturity;DPM,days from sowing to physiological maturity. B,simple linear regressions of DS/DPM and AFPD/DPM. DS/DPM,ratio of DS vs.DPM;AFPD/DPM,ratio of AFPD vs.DPM. **,significant at the 0.01 probability level.

3.3.The stability of grain-filling characteristics

The stability of grain-filling characteristics will be affected by multiple-stresses,such as heat stress (Taoet al.2016),which is important for maintaining the stability of grain yield. The stability of grain-filling characteristics for each hybrid was evaluated by the calculation of CV across the different environments. Changes in CVs for the grain-filling characteristics were estimated by regression with the hybrid release year (Appendix H). The results showed that the CVs of grain-filling duration (T1and T2) and accumulated dry matter (W1,W2and W3) at all three phases,as well as the CV of grain-filling rate at the effective grain-filling phase (G2),decreased significantly.This result revealed that the stability of grain-filling characteristics has improved continuously for single-cross hybrids from the 1960s to the 2010s in China.

3.4.Comparison of grain-filling characteristics between Chinese local and U.S.hybrids

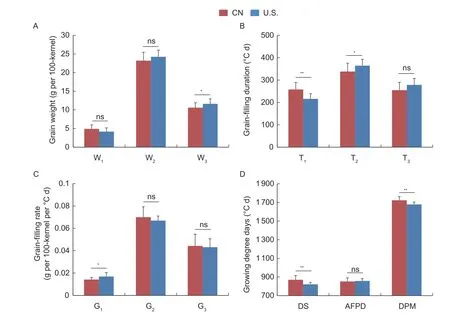

In this study,a total of 13 Chinese hybrids and 18 U.S.hybrids (Pioneer Company) released since 2000 were used to investigate the differences in grain-filling characteristics between Chinese local and exotic hybrids(Fig.4). Because most of the U.S.hybrids are not suited for the summer-sown environment,only the three spring environments of 14CP,15CP and 16CP were considered in the comparisons. The results showed that the grainfilling duration at the effective grain-filling phase (T2)for U.S.hybrids (with an average of 364.29°C d) was significantly higher than that of Chinese local hybrids (with an average of 338.01°C d). In contrast,the grain-filling duration at the lag phase (T1) of Chinese hybrids (with an average of 257.80°C d) was significantly higher than that of U.S.hybrids (with an average of 216.04°C d). Except for the lag phase,no significant differences in the grainfilling rates were observed in the following two phases,i.e.,the effective grain-filling phase and the maturation drying phase.

Fig.4 Differences in grain-filling characteristics and growth period traits between Chinese (CN) hybrids and the U.S.hybrids released since 2000 in three spring environments. A,changes in the accumulation of grain weight at different grain-filling phases. B,changes in grain-filling duration at different grain-filling phases. C,changes in grain filling rate at different grain-filling phases. D,changes in growth period traits. W1,accumulated dry matter in the lag phase;W2,accumulated dry matter in the effective grain-filling phase;W3,accumulated dry matter in the maturation drying phase;T1,grain-filling duration in the lag phase;T2,grain-filling duration in the effective grain-filling phase;T3,grain-filling duration in the maturation drying phase;G1,mean grain-filling rate in the lag phase;G2,mean grain-filling rate in the effective grain-filling phase;G3,mean grain-filling rate in the maturation drying phase;DS,days from sowing to silking;AFPD,actual grain-filling period duration;DPM,days from sowing to physiological maturity. Bars mean SE (Chinese hybrids,n=32;U.S.hybrids,n=18). ns,non-significant;* and **,significant at the probability of 0.05 and 0.01,respectively.

The accumulated dry matter in the lag phase (W1)of Chinese hybrids (4.88 g/100-kernel) was higher than that of U.S.hybrids (4.18 g/100-kernel). However,the accumulated dry matter in the maturation drying phase(W3) of U.S.hybrids (11.63 g/100-kernel) was significantly higher than that of Chinese hybrids (10.60 g/100-kernel). Moreover,under conditions of similar AFPD,the accumulated GDDs of DS and DPM of Chinese hybrids(DS,869.99°C d;DPM,1 723.29°C d) were significantly higher than those of U.S.hybrids (DS,820.73°C d;DPM,

1 678.44°C d). The differences in the CVs of grain-filling characteristics and growth period traits between Chinese and U.S.hybrids were also compared in this study(Appendix I). The U.S.hybrids displayed a lower CV value in HKW,while the CVs of T2,G1,G2and W2for U.S.hybrids were lower than those of the Chinese hybrids.

4.Discussion

In the U.S.,it was reported that the date of silk emergence showed little or no change over the decades that were studied (Duvick 2005). A study on another set of historically important maize hybrids in the U.S.found that the increase in grain-filling duration was the result of later physiological maturity rather than a change in flowering date (Cavalieri and Smith 1984). Therefore,the earlier silking emergence within the whole growth period (i.e.,the ratio of DSvs.DMP) may be one of the direct reasons for the improvement of maize hybrids.Further,a similar phenomenon was also observed in the breeding process of soybean,where the reproductive period is typically prolonged but the vegetative period is continuously becoming shorter (Sunet al.1990;Wanget al.2015). In our study,earlier silk emergence was also observed among the 50 hybrids released from the 1960s to the 2010s in China (Fig.3-A),which is also directly reflected by the continuous decrease in the ratio of DSvs.DPM and the increase in the ratio of AFPDvs.DPM (Fig.3-B). These results reflect the process of maize breeding in China. In the early decades of hybrid breeding,compared with the earlier maturing hybrids,the later hybrids that tended to have a longer grain-filling duration dominated the seed market. However,due to the limitations of the local environments,DPM could not be prolonged indefinitely,and thus,the new hybrids obtained a longer AFPD by earlier silk emergence in the more recent breeding selection.

Kernel formation is directly determined by the grainfilling duration and grain-filling rate. In the U.S.,the accumulated GDDs of AFPD increased with decadal changes of 19.8 or 21.7°C d in two-year experiments for maize hybrids released from 1930 to 1982,while the grain-filling rate was not correlated with the year of hybrid release (Cavalieri and Smith 1984). In our study,a significant decadal increase was observed for AFPD(23.41°C d). Meanwhile,a significant increase in the grain-filling duration period was also observed at the effective grain-filling phase and the maturation drying phase. This was similar to what occurred in the U.S.: the grain-filling duration period had played important roles in the improvement of maize hybrids. However,diverse grain-filling rates could be observed in the tested hybrids.Meanwhile,considering the contribution of grain-filling rate to the yield,selection on the grain-filling rate should be another focus in future maize breeding.

The identification of comparative advantages between local and exotic hybrids is crucial for future breeding strategies in China. Significant increases in the days to silk emergence have been found in Chinese hybrids from 1964 to 2001 but not in U.S.hybrids (Liet al.2011).In the present study,compared with the exotic hybrids released since 2000,Chinese local hybrids displayed significantly higher accumulated GDDs for DS (Fig.4).Meanwhile,the accumulated GDDs of DPM for Chinese hybrids was 44.85°C d (approximately 2-3 days),which is higher than those of the U.S.hybrids. However,there was no significant difference in AFPD between the Chinese local and U.S.hybrids. Therefore,the advance of silk appearance during the growth period could be one of the comparative advantages of the U.S.hybrids,which contributes to the increase in the grain-filling period duration.

There was a shift in the philosophy of hybrid evaluation in the United States after the 1980s. According to this philosophy,maize breeders should pay more attention to evaluations with relatively low precision at a large number of locations instead of evaluations with high precision at a small number of locations (Bradleyet al.1988). This strongly contrasts with the actual breeding practices of China,especially in the last century. At that time,according to the capacity for affordable yield testing,hybrids were tested only in limited environments before their release. However,the hybrids released by Pioneer often are subjected to testing in over 200 environments before their release,even in China (Bai 2007). In the present study,the U.S.hybrids generally showed higher environmental stability in their grain-filling characteristics compared with Chinese local hybrids released in the same era. This result reveals the differences in breeding strategies between Chinese local breeders and international seed companies at that time. Thus,intensive yield testing should be another crucial focus for local breeding in China.

5.Conclusion

In this study,the results showed that a significant increase in AFPD occurred for single-cross Chinese hybrids since the 1960s. However,there were no significant changes in the grain-filling rates across the environments.Meanwhile,we observed earlier silk appearance for the exotic hybrids from the Pioneer Company compared with the hybrids released by Chinese local breeders,which reveals the differences in strategies and resources between Chinese local and exotic breeding practices.Moreover,a significant increase in the stability of grainfilling characteristics across environments was also identified. Therefore,the main conclusion is that the relatively longer grain-filling duration,shorter DS,higher grain-filling rate,and steady grain-filling characteristics might greatly contribute to the yield improvement of maize hybrids in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0100303 and 2016YFD0100103),the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Non-Profit of Institute of Crop Sciences,Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Y2020YJ09 and CAAS-ZDRW202109),and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program,China (ASTIP). The authors are especially grateful to the CAAS technicians and to those at each of the field locations for seed preparation and field experiment assistance.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on http://www.ChinaAgriSci.com/V2/En/appendix.htm

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年3期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年3期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Germinated brown rice relieves hyperlipidemia by alleviating gut microbiota dysbiosis

- Melatonin treatment alleviates chilling injury in mango fruit 'Keitt'by modulating proline metabolism under chilling stress

- Changes in the activities of key enzymes and the abundance of functional genes involved in nitrogen transformation in rice rhizosphere soil under different aerated conditions

- Growth and nitrogen productivity of drip-irrigated winter wheat under different nitrogen fertigation strategies in the North China Plain

- Effect of fertigation frequency on soil nitrogen distribution and tomato yield under alternate partial root-zone drip irrigation

- Phylogenetic and epidemiological characteristics of H9N2 avian influenza viruses in Shandong Province,China from 2019 to 2021