Less hairy leaf 1,an RNaseH-like protein,regulates trichome formation in rice through auxin

CHEN Hong-yan,ZHU Zhu,WANG Xiao-wen,Ll Yang-yang,HU Dan-ling,ZHANG Xue-fei,JlA Lu-qi,CUl Zhi-bo,SANG Xian-chun

Key Laboratory of Application and Safety Control of Genetically Modified Crops,Rice Research Institute,Academy of Agricultural Sciences,Southwest University,Chongqing 400715,P.R.China

Abstract The trichomes of rice leaves are formed by the differentiation and development of epidermal cells.Plant trichomes play an important role in stress resistance and protection against direct ultraviolet irradiation.However,the development of rice trichomes remains poorly understood.In this study,we conducted ethylmethane sulfonate (EMS)-mediated mutagenesis on the wild-type (WT) indica rice ‘Xida 1B’.Phenotypic analysis led to the screening of a mutant that is defective in trichome development,designated lhl1 (less hairy leaf 1).We performed map-based cloning and localized the mutated gene to the 70-kb interval between the molecular markers V-9 and V-10 on chromosome 2.The locus LOC_Os02g25230 was identified as the candidate gene by sequencing.We constructed RNA interference (LHL1-RNAi) and overexpression lines(LHL1-OE) to verity the candidate gene.The leaves of the LHL1-RNAi lines showed the same trichome developmental defects as the lhl1 mutant,whereas the trichome morphology on the leaf surface of the LHL1-OE lines was similar to that of the WT,although the number of trichomes was significantly higher.Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis revealed that the expression levels of auxin-related genes and positive regulators of trichome development in the lhl1 mutant were down-regulated compared with the WT.Hormone response analysis revealed that LHL1 expression was affected by auxin.The results indicate that the influence of LHL1 on trichome development in rice leaves may be associated with an auxin pathway.

Keywords: rice,trichome,gene cloning,auxin

1.lntroduction

On the external surfaces of plant organs,a variety of trichome types may develop,which vary in shape,size and function (Serna and Martin 2006).As a component of the epidermis,trichomes can act as a mechanical barrier against adverse environmental factors,thereby protecting the organs from external hazards (Yang and Ye 2013;Niuet al.2019),such as intense ultraviolet irradiation and extreme temperatures.Densely distributed non-glandular hairs may prevent excessive water loss from plant tissues under drought stress (Pattanaiket al.2014;Liuet al.2017).

Three types of trichomes can be found on rice leaves:macro-hairs,micro-hairs,and glandular-hairs (Zhanget al.2012).Previous research on rice trichomes has tended to focus on the hairs present on leaves and glumes,and has only identified or isolated genes or quantitative trait loci involved in the positive regulation of epidermal hair development (Liu Let al.2015;Liu L Cet al.2015).Currently,the genes associated with trichome development that have been identified in rice compriseOsWOX3B(GLR1,NUDA/GL-1/dep,GL5) (Liet al.2012;Zhanget al.2012;Sunet al.2017),GL6(HL6) (Sunet al.2017;Xieet al.2020),GLR2(Wanget al.2013),GLR3(OsSPL10) (Lanet al.2019;Li J Qet al.2021),gl1(Liet al.2010),GLL(Dongchenet al.2015),andSDG714(Dinget al.2007).Mutations of these genes often lead to a reduced density or absence of trichomes on the leaves or glumes.Among these genes,OsWOX3BandGL1play a role in the early stages of trichome development (Liet al.2010,2012),HL6regulates the elongation of macro-hairs (Zenget al.2013),GLR3regulates the development of the trichome (Lanet al.2019),GLR2regulates the formation of macro-and micro-hairs (Wanget al.2013),andGLLparticipates in the regulation of epidermal cell differentiation (Dongchenet al.2015).

Phytohormones are important regulators of hair development.The plant hormones salicylic acid (Zhanget al.2018),gibberellins (GAs) (Ganet al.2006),jasmonic acid (JA) (Huaet al.2021),auxin,and cytokinin (CK) (Kanget al.2010) are all involved in the initiation of trichome development.While GAs and JA increase the number and density of trichomes,salicylic acid has the opposite effect (Chien and Sussex 1996;Traw and Bergelson 2003).InArabidopsis,trichome initiation is controlled by GAs in rosette leaves.A genetic cascade in the epidermis is activated by GAs to initiate the formation of trichomes(Matías-Hernándezet al.2016).Jasmonic acid affects the trichome length in tomato by releasing JASMONATE ZIM-domain (JAZ) protein-mediated transcriptional inhibition (Huaet al.2021).Gibberellins and JA induce the degradation of DELLA and JAZ proteins to coordinate the activation of the MYB-bHLH-WD40 trimeric complex,which indicates that GA and JA signals are coordinated to regulate trichome development (Qiet al.2014).The simultaneous application of exogenous cytokinin and GA in cucumber had no effect on the size of the glandular hairs,although the number of epidermal hairs was shown to increase with increased hormone concentrations (Kanget al.2010).TINY BRANCHED HAIR(TBH) is expressed preferentially in multicellular trichomes,and regulates the development of multicellular trichomes and sex expression through an ethylene pathway (Zhang Yet al.2021).The auxin-responsive geneSlARF3is involved in the formation of epidermal cells and trichomes in tomato (Zhanget al.2015).

In this study,we identified thelhl1mutant that shows defective leaf trichome development.Map-based cloning,phenotypic analysis,RT-qPCR analysis,and auxin response analysis all indicate that trichome development in rice may be associated with the auxin pathway.These results lay the foundation for further research on the molecular mechanisms associated with the development of leaf trichomes in rice.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Plant materials and investigation of agronomic traits

A hairy leaf mutant,designatedlhl1,was selected from a population ofindicarice ‘Xida 1B’ subjected to ethylmethane sulfonate (EMS)-mediated mutagenesis.After multiple generations of selfing,the mutant phenotype was genetically stable.The male parent used for gene mapping was ‘Jinhui 10’,a wildindicarice cultivar.The test materials were grown at the Xiema Rice Experimental Station in Chongqing,China.During the rice maturity period,10 plants in the centre of each wild-type (WT) ‘Xida 1B’ andlhl1mutant plot were selected in order to investigate their agronomic traits,such as plant height,panicle length,tiller number,grain length,thousand-grain weight,etc.(Appendices A and B),which were recorded for three consecutive years and the data were subjected to statistical analysis.

2.2.Scanning electron microscopy

From the tillering stage,the leaves of thelhl1mutant were smoother than those of the WT.WT and mutant leaves at the mature stage were sampled for observation by scanning electron microscopy (SU3500;Hitachi).The adaxial and abaxial surfaces of the leaves were observed,and the number and morphology of leaf trichomes were recorded.

2.3.Map-based cloning of LHL1

A population derived from the cross betweenindicarice‘Jinhui 10’ (the female parent) and thelhl1mutant (the male parent) was generated for genetic analysis and gene mapping.Using the F2population,10 WT and 10 mutant individuals were sampled to form a WT pool and a mutant gene pool,respectively.Based on the complete genome sequence of rice,and using molecular markers developed in our laboratory,12 pairs of molecular markers that were polymorphic between ‘Jinhui 10’ and thelhl1mutant were screened for linkage analysis,and markers linked to the mutated locus were then selected for further screening (Appendix C).In order to verify the linkage markers,a larger F2mapping population was generated using F2individuals that exhibited the mutant phenotype,and new molecular markers were designed to narrow the positioning interval.The existing annotations for genes located within the fine-mapping interval were recorded,and sequence verification of the mutated gene was undertaken(Appendix D).

2.4.Vector construction

Construction of the complementary vector pCAMBlA1301-LHL1With reference to the gene sequence available from the database of the China Rice Data Center(https://www.ricedata.cn/),Vector NTI 10 Software was used to design a pair of gene-specific primers to amplify the entire coding sequence (CDS) ofLHL1together with the 2 700 bp promoter region upstream of the start codon(ATG) and the 1 000 bp region downstream of the stop codon(TAA).Using WT ‘Xida 1B’ DNA as the template,the primer pairLHL1-COM-F/R was used for fragment amplification(Appendix E).A complementary vector was constructed with the pCAMBIA1301 plasmid as the backbone.

Construction of the overexpression vector S65T-2-LHL1The Vector NTI 10 Software was used to design specific upstream and downstream primers,with WT cDNA as the template.The primer pairLHL1-OE-F/R was used to amplify the CDS ofLHL1(Appendix E).A complementary vector was constructed with the S65T-2 plasmid as the backbone.

Construction of the interference vector pTCK303-LHL1A 300-bp specific fragment was selected from the CDS exon ofLHL1.Two pairs of specific primers were designed using Vector NTI 10 (Appendix E).The WT cDNA was used as the template to amplify the sense and antisense strands of the sequence.Following double digestion of the pTCK303 plasmid and sense strand,the products were ligated.We then cut the ligated pTCK303 plasmid+sense strand and antisense strand,and connected the products after digestion.

2.5.Expression pattern analysis

RT-qPCR analysisAt the tillering stage,the WT andlhl1mutant plants with uniform growth were selected,and leaves at the same position were selected for RNA extraction and reverse transcription into cDNA.After designing the quantitative primers,RT-qPCR analysis was performed using the cDNA as the template.

Semi-quantitative PCR analysisTotal RNA was extracted from various tissues of the WT andlhl1mutant plants at the same developmental stage,and used as the template for reverse transcription of cDNA.A pair of specific quantitative primers were designed using the Vector NTI 10 Software.The cDNA was used as the template for PCR amplification.The expression ofLHL1was detected by agarose gel electrophoresis.TheUbqgene was used as an internal reference.

Subcellular locationFrom 10-day-old WT seedlings,protoplasts were extracted from the young stems,theBZR1-mCherry fusion protein was used as the nuclear localization signal to co-transform the rice protoplasts with pAN580-LHL1,and the signal was observed after overnight expression.

2.6.Auxin response analysis

WT ‘Xida 1B’ seedlings were grown in a hydroponic medium for 10 days before treatment with 5 μmol L–12,4-D.The control seedlings were treated with water.At 0,3,6,9,12,and 24 h after treatment,the whole seedlings were used for the extraction of total RNA,which was reverse transcribed into cDNA for RT-qPCR analysis.

3.Results

3.1.Reduced number of trichomes on leaves of the lhl1 mutant

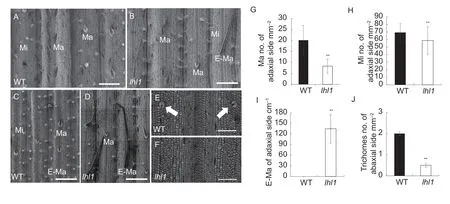

At the tillering stage,thelhl1mutant leaves were smoother than those of the WT,and RT-qPCR of the wax-related genes and scanning electron microscopy revealed that the waxiness of the leaves was only slightly defective in the mutant (Appendix F).Leaves from the WT andlhl1mutant plants were sampled for scanning electron microscopy.Examination of the adaxial surfaces revealed that the number of trichomes on the large and small vascular bundles of thelhl1mutant was significantly reduced compared to the WT (Fig.1-A and B).Statistical analysis revealed that the numbers of macro-hairs (Ma)and micro-hairs (Mi) on the adaxial surface oflhl1mutant leaves were significantly lower than in the WT (Fig.1-G and H).The trichomes on the small vascular bundles in thelhl1mutant were elongated,and elongated macrohairs (E-Ma) developed;but the same phenomena were not observed in the WT (Fig.1-A–D).Compared with the WT,the number of E-Ma in thelhl1mutant was significantly greater (Fig.1-I).The trichomes on the abaxial surface of the WT leaves are more rare and smaller,whereas almost no trichomes at all developed on the abaxial surface in thelhl1mutant (Fig.1-E,F and J).These observations show that the smoother leaves of thelhl1mutant were caused by a reduced number of trichomes.

Fig.1 Trichome development on leaves of wild type (WT) and lhl1 of rice. A–D,scanning electron micrographs of trichomes on the adaxial surface of leaves;bar=200 μm.Mi,micro-hair;Ma,macro-hair;E-Ma,elongated macro-hair.E and F,scanning electron micrographs of trichomes on the abaxial surface of leaves.The white arrows indicate trichomes.Bar=100 μm.G–I,number of trichomes on the adaxial surface of leaves.J,number of trichomes on the abaxial surface of leaves.Bars mean SD(n=3).**,P<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

3.2.LHL1 is located on chromosome 2 and encodes an RNaseH-like domain-containing protein

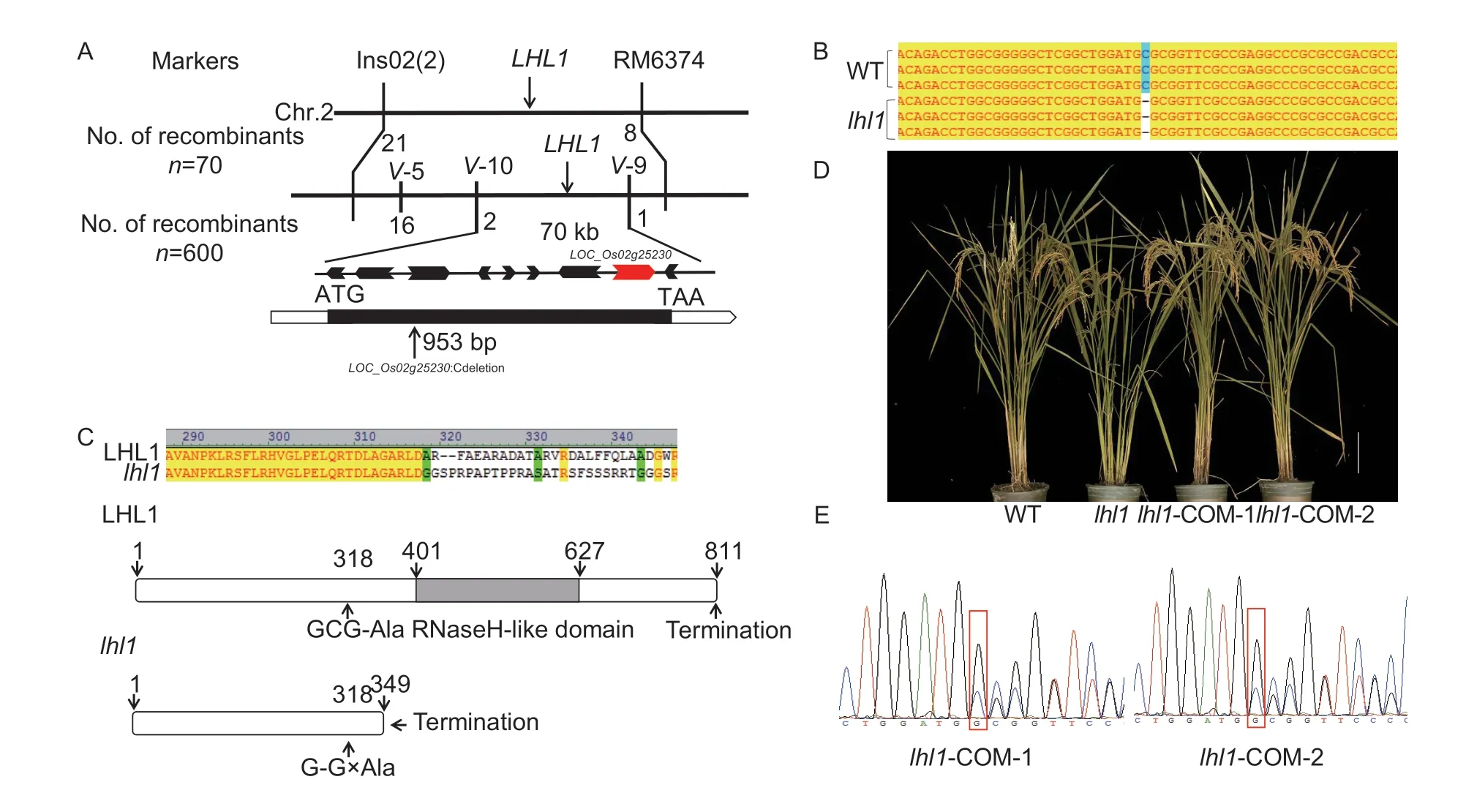

A hybrid combination oflhl1and the WT restorer line Jinhui 10 was prepared,and the phenotype of the F1population was similar to that of the WT,but the F2population obtained by selfing the F1individuals showed trait segregation.A chisquare test revealed that the segregation followed a ratio of 3:1,which indicates that thelhl1phenotype was controlled by the mutation of a single gene.Through map-based cloning,the mutated gene was located in an interval of 70 kb between the V-10 and V-9 markers on chromosome 2(Fig.2-A).Nine genes were annotated in this interval,and DNA sequencing revealed thatLOC_Os02g25230was mutated.The 953rd base C in the exon was deleted,and this locus therefore appeared to be the candidate gene (Fig.2-B).For verification,a complementary vector containing the gene was constructed and transformed intolhl1mutant plants.Observations of positive complementary plants revealed that the phenotype was restored to that of the WT.DNA from the positive complementary plants was then extracted and sequenced,which confirmed that the candidate gene wasLOC_Os02g25230(Fig.2-D and E).

Fig.2 Map-based cloning of LHL1 and amino acid sequence analysis.A,map-based cloning of LHL1.B,base sequences of wild type (WT) and lhl1.C,amino acid sequences and structures of LHL1 and lhl1.D,phenotype observation of the complementary line,bar=10 cm.E,sequence trace of the mutation site in lhl1-COM.

TheLHL1locus was annotated as an expressed protein with a single exon in the China Rice Data Center database (https://www.ricedata.cn/gene/).Analysis of theLHL1sequence using InterProScan 5 (Quevillonet al.2005) revealed that it contained an RibonucleaseH-like(RNaseH-like) domain at amino acids 401–627 (Fig.2-C).Thus,LHL1encodes an RNaseH-like superfamily domaincontaining protein.However,the frameshift mutation caused by the deletion of the C base stops the protein translation prematurely at the 349th amino acid,so the mutant protein cannot form an RNaseH-like domain (Fig.2-C).

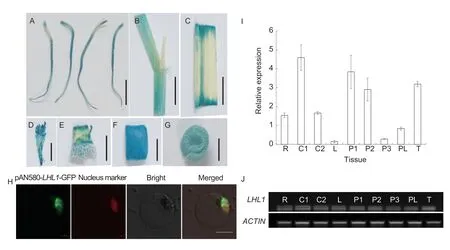

3.3.Expression patterns of LHL1

To explore the tissue-specific expression pattern ofLHL1,we performed β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining of different organs fromLHL1promoter+GUS positive transgenic plants.The results of the staining showed thatLHL1was expressed in the roots,leaves,young panicles,tiller buds,stems,and sheaths (Fig.3-A–G).Subsequently,total RNA from each of these tissues was extracted for RT-qPCR and semi-quantitative analyses.Expression ofLHL1was the highest in sheaths,young panicles,and tiller buds,and the semi-quantitative results were consistent with the RT-qPCR results (Fig.3-I and J).Next,we examined the cell-level expression pattern ofLHL1by transforming the construct pAN580-LHL1into rice protoplasts and performing confocal laser microscopic observation after incubation overnight.The fluorescence signal of theLHL1-GFP fusion protein was concentrated in the nucleus,which overlapped with the nuclear localization signal ofBZR1-mCherry (Fig.3-H).This result indicates that LHL1 is localized in the nucleus.

Fig.3 Expression pattern analysis. A–G,β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining of the different tissues.Bar=0.5 cm.H,subcellular localization of LHL1.Bar=5 μm.I,analysis of LHL1 expression in different tissues.Bars mean SD (n=3).J,semi-quantitative analysis of LHL1 expression in different tissues.R,root;C1,young stem;C2,mature stem;L,leaf;P1,panicles of length <0.5 cm;P2,panicles of length 0.5–1 cm;P3,panicles of length 1–2 cm;PL,panicle stem shaft;T,tiller buds.

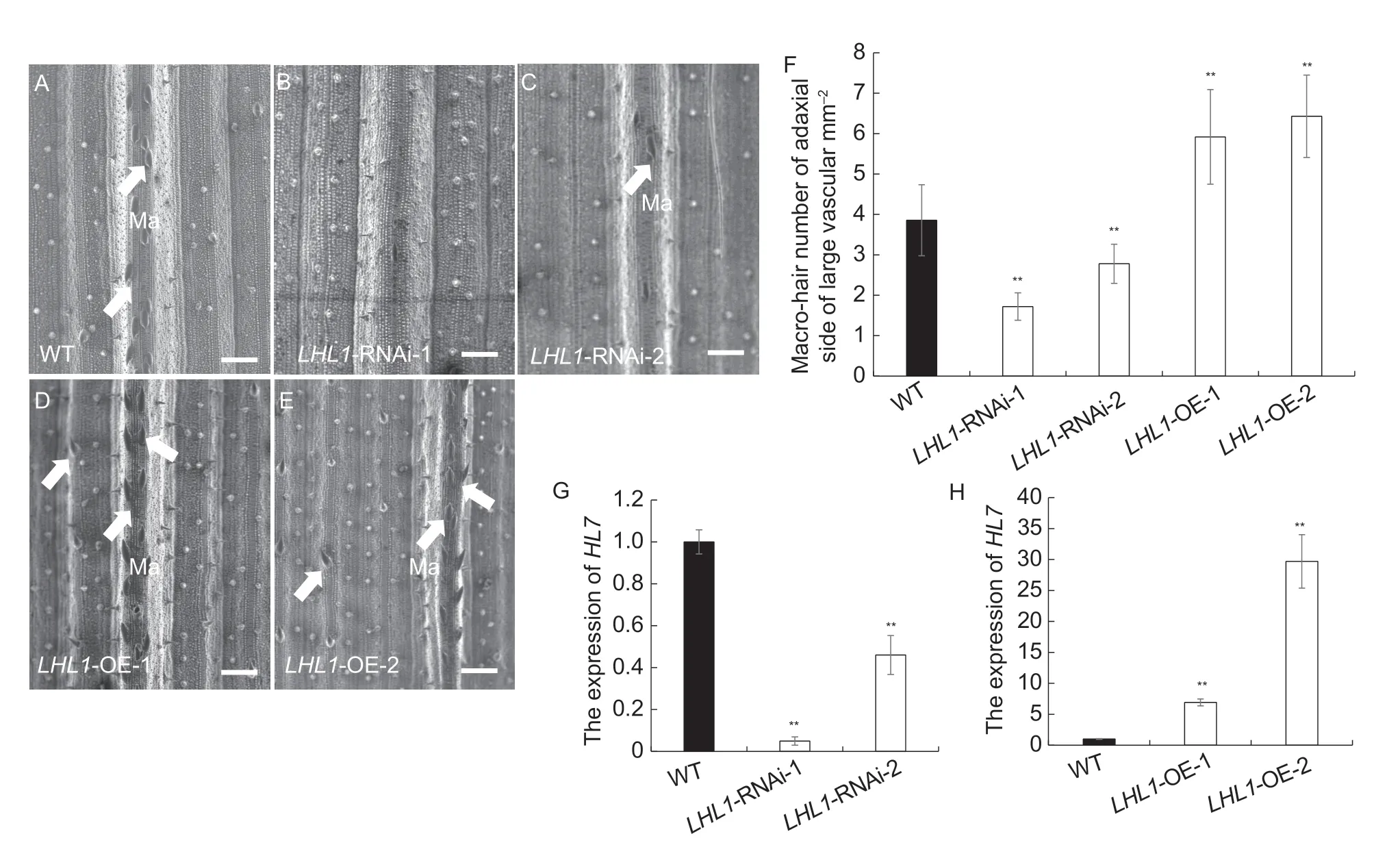

3.4.Trichome development in overexpression and RNA interference transgenic lines

For further analysis of the effect ofLHL1on the development of leaf trichomes in rice,we constructed overexpression(LHL1-OE) and RNA interference (LHL1-RNAi) transgenic lines.The expression levels ofLHL1in the WT,LHL1-RNAi,andLHL1-OE lines were quantified by RT-qPCR.Compared with that of WT,the expression levels ofLHL1were the highest in theLHL1-OE lines,and the lowest in thelhl1mutant andLHL1-RNAi lines (Fig.4-G and H).The leaf surfaces of the overexpression and interference transgenic lines were observed using scanning electron microscopy (Fig.4-A–E).The number of Ma in the interference lineLHL1-RNAi was considerably lower than in WT,but in the overexpression lineLHL1-OE,the number of Ma was significantly greater than in the WT (Fig.4-F).These observations also indicate that the number of Ma on the adaxial surface of the leaves was positively correlated withLHL1expression,indicating that LHL1 promotes the formation of Ma on the adaxial surface of rice leaves.

Fig.4 Expression of LHL1 and trichome development in overexpression and RNA interference transgenic lines.A,macro-hairs on the adaxial surface of leaves of wild type (WT).B and C,macro-hairs on the adaxial surface of leaves of LHL1-RNAi.D and E,macro-hairs on the adaxial surface of leaves of LHL1-OE.A–E,bar=100 μm.The white arrows indicate macro-hairs.F,statistical data of the number of macro-hairs on the adaxial surface of leaves.G and H,relative expression levels of LHL1.F–H,bars mean SD (n=3).**,P<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

3.5.LHL1 may affect trichome development through the auxin pathway

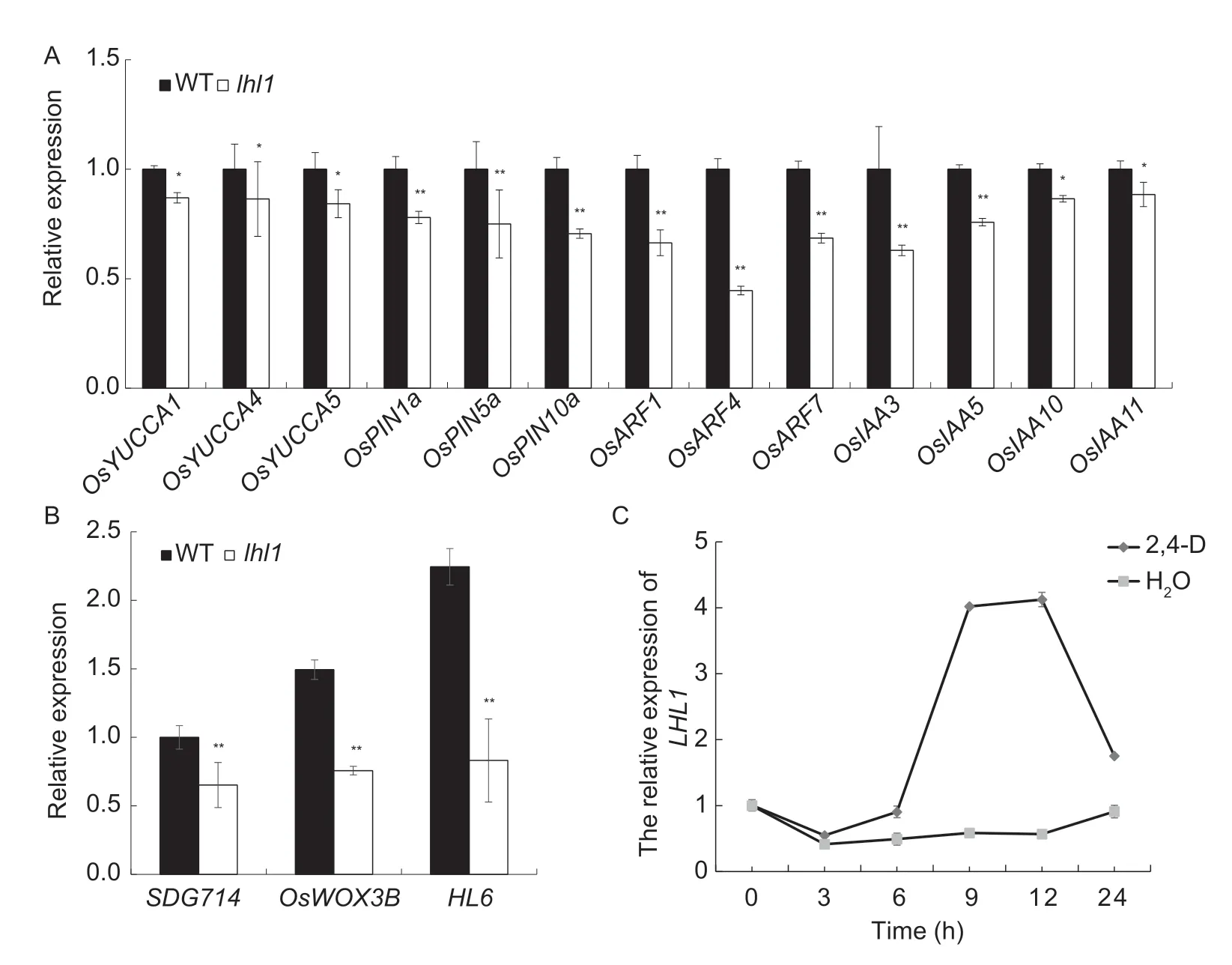

A recent study reported that TAC4 regulates the development of the tillering angle through the auxin pathway (Li Het al.2021).Knowing thatLHL1is an allele ofTAC4,we assessed the tillering angle of thelhl1mutant and found that compared with WT,the tillering angle oflhl1was indeed greater (Appendix F).To explore whether the effect oflhl1on trichome development in rice leaves is related to the auxin pathway,we selected several genes associated with the auxin pathway for RT-qPCR analysis,including genes associated with auxin synthesis(OsYUCCA1,OsYUCCA4,andOsYUCCA5),transportrelated genes (OsPIN1a,OsPIN5a,andOsPIN10a),and signalling-related genes (OsARF1,OsARF4,OsARF7,OsIAA3,OsIAA5,OsIAA10,andOsIAA11).Compared with WT,the expression levels of the genes associated with the auxin signalling pathway in thelhl1mutant were significantly lower (Fig.5-A).This finding indicates that the influence ofLHL1on trichome development may be through the auxin signalling pathway.

To determine whetherLHL1is regulated by auxin signalling,we conducted an auxin signal response analysis.Compared with the control,the expression level ofLHL1began to increase at 6 h after 2,4-D treatment,peaked between 9 and 12 h after treatment,and declined thereafter(Fig.5-C).This finding indicates thatLHL1expression may be induced by auxin.Among the genes reported to be associated with trichome development in rice,SDG714,HL6,andOsWOX3Bare positive trichome regulatory genes,and the regulation of trichome development byHL6andOsWOX3Bis also known to be associated with auxin.We performed RT-qPCR analysis and observed that the expression levels ofSDG714,OsWOX3B,andHL6in thelhl1mutant were significantly reduced compared with WT(Fig.5-B).These results provide a further indication that the defective trichome development in thelhl1mutant was related to an auxin pathway.

Fig.5 RT-qPCR analysis of auxin pathway-related and trichome development-related genes,and auxin signal response analysis.A,auxin pathway-related genes.B,trichome development-related genes.C,auxin signal response analysis.WT,wild type.Bars mean SD (n=3).*,P<0.05 and **,P<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

4.Discussion

4.1.LHL1 affects the formation of rice leaf trichomes

Among the genes that affect trichome development,the loss-of-function mutant ofSDG714(SET Domain Group Protein 714) lacks large trichomes on the glumes,leaves,and stems,thusSDG714positively regulates the development of Ma on rice leaves (Dinget al.2007).Thegl1mutation causes the phenotypic traits of hairless leaves and glumes;while the non-mutated gene,which belongs to theWUS-type homeobox (WOX) gene family and was namedOsWOX3B(Zhanget al.2012),regulates trichome formation on the leaves and glumes (Liet al.2012;Zhanget al.2012).Glabrous Rice 1(GLR1) encodes a homeodomain protein containing aWOXmotif and also controls trichome development on the leaves and glumes (Liet al.2012).In contrast,LHL1only regulates the formation of leaf trichomes,having little effect on glume trichomes.Unlike in leaves,the RT-qPCR analysis of trichome-related genes in glumes indicated that the expression levels ofSDG714andOsWOX3Bshowed no significant difference compared with WT,while the expression ofHL6was upregulated (Appendix G).The differences in the expression of these genes may be the reason that the development of trichomes in glumes is different from that in leaves.The number of Ma in the OsWOX3Boverexpression lines was significantly higher,but the trichome length was unchanged (Sunet al.2017).In addition,HL6is an AP2/ERF transcription factor that regulates trichome elongation and affects trichome formation in rice.As well as regulating the number of trichomes,LHL1also has an effect on macrohair length (Fig.1-D).

In the present study,mutations inLHL1led to a decrease in the number of leaf trichomes,including the numbers of macro-and micro-hairs,on the adaxial and abaxial surfaces of leaves (Fig.1).In the RNA interference lineLHL1-RNAi,the number of trichomes was greatly reduced,whereas in the overexpression lineLHL1-OE,the number of trichomes was increased significantly compared to WT (Fig.4).We therefore inferred that the number of trichomes that develop is positively correlated with the expression ofLHL1,and LHL1 positively regulates the number of trichomes.The present RT-qPCR analysis of genes associated with the development of rice trichomes reveals that the expression levels ofSDG714,OsWOX3B,andHL6were significantly reduced in thelhl1mutant compared with WT (Fig.5-B).SDG714,OsWOX3B,andHL6are all related genes that positively regulate trichome development in rice,and the reduction in their expression levels in thelhl1mutant may thus be an internal cause of the observed defective trichome formation.

4.2.LHL1 encodes an RNaseH-like domain-containing protein

lhl1is a hairless mutant of rice.Gene mapping and sequencing has revealed thatLHL1is a new allele ofTAC4(Li Het al.2021),arising from deletion of the base C at position 953 in the exon.The subsequent shift in the base frame halts protein translation prematurely (Fig.2-C),and results in a phenotype with a reduced number of trichomes on the surface of the leaves.Sequence analysis of LHL1 has shown that it contains an RNaseH-like domain,so it is a member of the RNaseH-like superfamily,on which few functional studies have been undertaken to date.The RNaseH-like superfamily,also known as the retroviral integrase superfamily,is reportedly involved in many biological processes,including replication and homologous recombination,DNA repair,transposition,and RNA interference (Majoreket al.2014).In yeast,the Prp8 RNaseH-like domain inhibits Brr2-mediated U4/U6 snRNA unwinding by preventing Brr2 from loading on U4 snRNA(Mozaffari-Jovinet al.2012).In addition,the abnormal mechanism of self-initiated reverse transcription requires the RNaseH domain of reverse transcriptase to cleave the RNA duplex (Levinet al.1996).

The barley geneELIGULUM-Aregulates the development of side branches and leaves.Mutations inELI-Areduce the plant height and number of tillers,disrupt the leaf–sheath boundary,suppress leaf ligule development,and reduce the development of secondary cell walls in stems and leaves(Okagakiet al.2018).The present phylogenetic analysis has revealed that its homologous genes in rice includeLHL1(Appendix H).A homology analysis of the barleyELI-Asequence supports this contention,and confirms that barleyELI-Aand its rice homologs contain the RNaseH-like domain (Okagakiet al.2018).However,we observed that leaf ligule development was not defective in thelhl1mutant in rice (Appendix F).In rice andArabidopsis,the function of the RNaseH-like superfamily remains unclear.LHL1 is described only as an expressed protein in the database of the China Rice Data Center (https://www.ricedata.cn/gene/).TheArabidopsisgenome contains two homologous genes,AT1G12380andAT1G62870,but mutated phenotypes of these two genes and their related functions have not yet been reported.

4.3.LHL1 effects on trichome development and plant architecture in rice may be associated with an auxin pathway

The impact of LHL1 on rice is not limited to the trichomes,but also includes plant height,tiller number,grain size,1 000-grain weight,etc.(Appendices A and B).We speculate that the diversity of these effects is related to auxin.The loss of LHL1/TAC4 function will affect the synthesis and transport of auxin (Li Het al.2021),and the effect of auxin on rice is pleiotropic,including features such as plant height,tiller,yield,etc.According to several reports,the functional auxin eラux transporterOsPIN9positively regulates the number of tillers in rice (Houet al.2021).In addition,OsmiR160can negatively regulate the expression ofOsARF18through the auxin pathway to affect the growth and development of rice (Huanget al.2016).BG1can positively regulate plant biomass,seed weight and yield,it is specifically induced by auxin treatment,and its loss of function will reduce auxin transport (Liu Let al.2015;Liu L Cet al.2015).Rice plants carrying theDNR1indicaallele have shown enhanced auxin biosynthesis,resulting in increased grain yield (Zhanget al.2021).Therefore,LHL1/TAC4 can exert its pleiotropy in rice by regulating the auxin pathway.In addition,previous studies have shown that trichome development is closely associated with auxin.Treatments with different concentrations of methyl jasmonate,GA,and indoleacetic acid (IAA) cause the density of the two types of glandular hairs to increase significantly (Liuet al.2016).The protein encoded bySlIAA15,a member of the tomato Aux/IAA family,acts as a strong repressor of auxin-dependent transcription.Down-regulation ofSlIAA15results in a reduced number of trichomes,which indicates that trichome initiation requires auxin-dependent transcriptional regulation(Denget al.2012).TaIAA15sgenes can also regulate plant architecture in wheat (Liet al.2020).This evidence indicates that auxin is essential for trichome development.

We selected auxin pathway genes for RT-qPCR analysis and observed that the expression of these genes in thelhl1mutant was significantly reduced compared with the WT (Fig.5-A).This finding also indicates that,in general,the effect ofLHL1on trichome development is associated with the auxin signalling pathway.In rice,genes known to affect trichome development and related to auxin signalling,such asHL6,promote trichome elongation by inducing the expression of the auxin-related genes,and HL6 can strengthen this promotion effect by physically combining with OsWOX3B (Sunet al.2017).In the present study,the expression levels of theOsYUCCAs,OsPINas,OsARFs,andOsIAAsgenes in thelhl1mutant were also significantly lower (Fig.5-A).OsWOX3B is reported to be a crucial regulatory factor for hairless leaves in rice (Zhanget al.2012;Sunet al.2017).The reduced expression ofOsWOX3BandHL6in thelhl1mutant also suggests that LHL1 affects trichome development and the correlations between auxin pathways (Fig.5-B).In addition,Liet al.(2021) observed that TAC4 regulates the auxin pathway to affect the development of the tillering angle in rice.As an allele ofTAC4,the tillering angle of thelhl1mutant was also significantly higher (Appendix F).By conducting hormone response experiments,we found that LHL1 expression is induced by auxin (Fig.5-C).In addition,the results of the auxin recovery experiment indicate that the number of lateral roots increased significantly after the application of 0.05 μmol L–12,4-D (Appendix I).This finding provides further confirmation that the effect of LHL1 on trichome development is associated with an auxin pathway.

5.Conclusion

LHL1encodes an RNaseH-like protein belonging to the RNaseH-like protein family,which is expressed in the most of organs examined,such as root,stem,leaves,tiller buds and panicle.The loss of function ofLHL1leads to a reduced number of leaf trichomes and generates the elongated macro-hairs on the adaxial surfaces.RT-qPCR of auxin related genes and auxin response indicates that the influence of LHL1 on trichome development on rice leaves may be associated with an auxin pathway.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing,China (cstc2020jcyj-msxm0539,cstc2015jcyjA80008),the National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program from the Ministry of Education,China (202110635082),and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171964,31171178).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on http://www.ChinaAgriSci.com/V2/En/appendix.htm

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年1期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2023年1期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Characterization of a blaCTX-M-3,blaKPC-2 and blaTEM-1B co-producing lncN plasmid in Escherichia coli of chicken origin

- Consumers’ experiences and preferences for plant-based meat food: Evidence from a choice experiment in four cities of China

- Farmers’ precision pesticide technology adoption and its influencing factors: Evidence from apple production areas in China

- Visual learning graph convolution for multi-grained orange quality grading

- lnfluence of two-stage harvesting on the properties of cold-pressed rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) oils

- Reduction of N2O emissions by DMPP depends on the interactions of nitrogen sources (digestate vs.urea) with soil properties