DNA methylation-mediated expression of zinc finger protein 615 affects embryonic development in Bombyx mori

Guan-Feng Xu ,Cheng-Cheng Gong ,Yu-Lin Tian ,Tong-Yu Fu ,Yi-Guang Lin ,Hao Lyu ,Yu-Ling Peng,Chun-Mei Tong,Qi-Li Feng,Qi-Sheng Song,Si-Chun Zheng,*

1 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Insect Developmental Biology and Applied Technology, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Insect Development Regulation and Applied Research, Institute of Insect Science and Technology, School of Life Sciences, South China Normal University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510631, China

2 Division of Plant Science and Technology, College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, University of Missouri, Columbia MO 65211, USA

ABSTRACT Cell division and differentiation after egg fertilization are critical steps in the development of embryos from single cells to multicellular individuals and are regulated by DNA methylation via its effects on gene expression.However,the mechanisms by which DNA methylation regulates these processes in insects remain unclear.Here,we studied the impacts of DNA methylation on early embryonic development in Bombyx mori.Genome methylation and transcriptome analysis of early embryos showed that DNA methylation events mainly occurred in the 5'region of protein metabolism-related genes.The transcription factor gene zinc finger protein 615(ZnF615) was methylated by DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1) to be up-regulated and bind to protein metabolism-related genes.Dnmt1 RNA interference(RNAi) revealed that DNA methylation mainly regulated the expression of nonmethylated nutrient metabolism-related genes through ZnF615.The same sites in the ZnF615 gene were methylated in ovaries and embryos.Knockout of ZnF615 using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing decreased the hatching rate and egg number to levels similar to that of Dnmt1 knockout.Analysis of the ZnF615 methylation rate revealed that the DNA methylation pattern in the parent ovary was maintained and doubled in the offspring embryo.Thus,Dnmt1-mediated intragenic DNA methylation of the transcription factor ZnF615 enhances its expression to ensure ovarian and embryonic development.

Keywords:DNA methylation; Embryonic development;Transcriptional regulation;Epigenetic

INTRODUCTION

The zygote is the starting point of embryonic development.Embryogenesis is a complex process regulated by genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in which a zygote develops into a multicellular individual.DNA methylation via 5-methylcytosine(5mC),i.e.,the covalent addition of a methyl (CH3) group to the fifth carbon of the pyrimidine ring of cytosine residues of DNA molecules (Razin &Riggs,1980;Yan et al.,2015),is an important epigenetic regulatory mechanism found in all species (Zilberman,2008).In mammals,many genes in regions where DNA methylation occurs are involved in embryogenesis and early embryonic development (Slieker et al.,2015).In mouse embryos,DNA methylation defects can affect chromosome structure and histone modification levels,resulting in early embryonic death (Takebayashi et al.,2007).In cow embryos,the methylation dynamics of X-inactive specific transcript (XIST) are essential for the initiation of X chromosome inactivation,which affects embryonic development (Dos Santos Mendon?a et al.,2019).In insects,DNA methylation is enriched in early embryos (Xu et al.,2022a).For example,5mC deficiency inBombyxmoricauses ovarian dysplasia and embryonic lethality (Xiang et al.,2013;Xu et al.,2021),and silencing of DNA methyltransferase 1(Dnmt1) inNasoniavitripennisandBlattellagermanicaresults in defective embryos (Ventós-Alfonso et al.,2020;Zwier et al.,2012).Therefore,DNA methylation is critical in animal embryogenesis.

In general,the establishment and maintenance of DNA methylation patterns are executed by an evolutionarily conserved family of DNA methyltransferases,including Dnmt3(denovoDNA methyltransferase) and Dnmt1 (maintenance DNA methyltransferase) (Bird,2002;Lister et al.,2009).Dnmt1 maintains pre-existing 5mC during DNA replication,while Dnmt3 is responsible for the generation of new 5mC sites (Glastad et al.,2011).In mammals,methylcytosine dioxygenase (TET3) is active,leading to low DNA methylation at the blastocyst stage,followed by Dnmt3a-and Dnmt3bmediateddenovoDNA methylation after blastocyst implantation (Greenberg &Bourc'his,2019;Smith et al.,2014).In some insects,Dnmt3 is absent,and Dnmt1 is responsible for bothdenovoand maintenance DNA methylation (Falckenhayn et al.,2013;Lyko &Maleszka,2011;Werren et al.,2010).However,the molecular and epigenetic mechanisms of Dnmt1 in the regulation of genomic DNA methylation in insect embryogenesis remain to be elucidated.

Many reports suggest that the mechanisms and patterns underlying genomic DNA methylation in insects differ from those in mammals (Glastad et al.,2011;Xiang et al.,2010;Xu et al.,2021;Zemach et al.,2010).In mammals,DNA methylation usually occurs in the promoter regions of target genes to create binding sites for specific transcription factors to activate the expression of tissue-specific genes or suppress the binding of transcription factors to promoters,resulting in altered transcriptional activity of the associated genes (Bird,2002;Rishi et al.,2010;Zilberman,2008).In mammalian cell nuclei,demethylation due to reprogramming (Byrne et al.,2003;Simonsson &Gurdon,2004) up-regulates octamerbinding transcription factor 4 (Oct4) to ensure normal development of the embryo (Boiani et al.,2002;Bortvin et al.,2003).In insects,however,although DNA methylation in gene promoters regulates wing development through chitin metabolism (Xu et al.,2018,2020),DNA methylation is enriched in gene bodies (Glastad et al.,2011;Xiang et al.,2010;Zemach et al.,2010).We previously found that intragenic DNA methylation recruits the acetylase Tip60 to enhance protein synthesis-related gene expression in theB.moriovary (Xu et al.,2021).

In this study,we analyzed the methylome and role ofDnmt1in early embryos ofB.mori,an economically valuable insect and model lepidopteran.We found that DNA methylation actively participated in embryogenesis by up-regulating the reproduction-specific transcription factor genezincfinger protein615(ZnF615) to enhance the expression of nutrient metabolism-related genes.Furthermore,the regulatory pathway was consistent between parent ovaries and offspring embryos.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insects and cell lines

TheB.moristrain P50 was obtained from the Research and Development Center of the Sericulture Research Institute of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences,Guangdong,China.The moths were reared on fresh mulberry leaves at 27 °C under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle.

TheB.moriBm12 (DZNU-Bm-12) cell line,originally derived from ovarian tissues (Khurad et al.,2009),was cultured at 28 °C in Grace’s medium (Invitrogen,USA)supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone,USA).

Dot blot assay

Genomic DNA was extracted from 50–60 silkworm embryos at each stage of embryonic development (i.e.,fertilized egg,blastoderm,germ-band,organogenesis,reversal period,and head pigmentation) and digested with RNase A (Promega,USA) to eliminate RNA contamination.Genomic DNA (500 ng)was denatured at 95 °C for 10 min and immediately cooled on ice.The resulting genomic DNA was spotted on a nitrocellulose blot polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane(GE Healthcare,China) and dried,followed by UV crosslinking for 1 min.The membrane was blocked with 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl,150 mmol/L sodium chloride,0.05% Tween-20,pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature,then incubated with mouse anti-5mC antibody (1:1 000;ab10805,Abcam,UK) overnight at 4 °C.After three washes in TBST (10 min each),the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked goat antimouse IgG secondary antibody (1:2 000;Dingguo Biotechnology,China) for 1.5 h at 37 °C.The input genomic DNA samples were spotted on the PVDF membrane,as indicated above,then directly stained with GoldViewTM(Dingguo Biotechnology,China).

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS)

Genomic DNA was fragmented into 100–300 bp fragments by sonication,and a single “A” nucleotide was added to the 3'end of the blunt fragments.The fragments with the adapter were then bisulfite-converted using a Methylation-Gold Kit(Zymo,USA).Finally,the converted DNA fragments were amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeqTM2500 platform by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co.(China).

The obtained clean reads were mapped to theB.morireference genome (Wang et al.,2005;Xia et al.,2004) using BSMAP (v2.90) (Xi &Li,2009).The methylation level was calculated based on the methylated cytosine percentages in the whole genome,in each chromosome,or in different regions of the genome for each sequence context (CG,CHG,and CHH).To assess differences in methylation patterns in different genomic regions,the methylation profiles in the flanking 2 kb regions and gene bodies (or transposable elements) were plotted based on the average methylation levels for each window.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis

Total RNA fromB.moriembryos was extracted using a TRIzol Reagent Kit (Invitrogen,USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.RNA quality was assessed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies,USA) and checked using electrophoresis on RNase-free agarose gel.RNA-seq was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencing platform by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co.(China).The raw reads were filtered to obtain clean reads,which were mapped to theB.morireference genome (Wang et al.,2005;Xia et al.,2004)using HISAT2 v2.4 (Kim et al.,2015) with “RNA-strandness RF” and other parameters set to default.The assembled transcripts were generated after mapping,and their expression levels were normalized using FPKM values(fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped) by Cufflinks (Trapnell et al.,2012).Analysis of differentially expressed transcripts (DETs) between two groups was performed using DESeq2 software (Love et al.,2014).Transcripts withP<0.05 and absolute fold-change≥2 were considered DETs.

Western blotting

For western blot analysis,40–100 μg of total protein extracted from embryos was separated using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE),followed by transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare,China).The membrane was blocked with 3% (w/v)BSA in TBST for 2 h at room temperature,followed by hybridization overnight at 4 °C in TBST containing 1% BSA and primary antibody (anti-Dnmt1 and anti ZnF 615).After washed in TBST three times,the membrane was then incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:2 000,Dingguo Biotechnology,China)for 2 h at 37 °C.Tubulin (Cat:TB002-R,Dingguo Biotechnology,China) was used as a reference to verify equal loading of the proteins on the gel.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSA was conducted using a LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific,USA).Methyl-or biotinconjugated oligonucleotide probes were heated at 95 °C for 10 min and then slowly cooled to room temperature.Binding assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.In brief,proteins were incubated for 20 min at room temperature with 20 μL of binding buffer (50 ng of poly(dI-dC),2.5% glycerol,0.05% NP-40,50 mmol/L potassium chloride,5 mmol/L magnesium chloride,4 mmol/L EDTA,and 20 fmol of biotinylated end-labeled double-stranded probe).Different concentrations of unlabeled cold probes or unmethylated mutant probes were added to the binding mixture as competitors.After electrophoresis,the proteins were blotted onto positively charged nylon membranes (Hybond Nt;Amersham Biosciences,UK),and the bands were visualized using the above EMSA kit according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of Dnmt1 and ZnF615

Small guide RNA (sgRNA) sites on the exons of target genes were designed using CRISPRdirect (http://crispr.dbcls.jp/)(Naito et al.,2015) based on the GN19NGG motif.A pair of primers was synthesized to amplify the fragment containing the T7 promoter,target site,and gRNA sequences.The PCR product was purified and used as the template for transcriptioninvitro.The sgRNA was synthesizedinvitrowith the MEGAscript T7 Kit (Ambion,USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and then purified with sodium acetate/ethanol.The quality of the purified product was analyzed by gel electrophoresis.

The fertilized eggs were collected within 2 h after oviposition and immediately placed on a clean glass slide for injection.The sgRNA and Cas9 proteins were mixed to a final concentration of 800 ng/μL and 600 ng/μL,respectively.The mixture was injected into the eggs using a micromanipulator(Eppendorf FemtoJet 4i and 4r,Germany).To prevent contamination,the eggs were disinfected by steaming in 10%formaldehyde for 5 min and then placed in an incubator at 27 °C under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle.All experimental operations were completed within 2 h of oviposition.

Identification of mutations at target sites

To confirm target gene mutation,the epidermis was collected for genomic DNA extraction when the silkworm larvae molted into pupae.Primers including regions upstream and downstream of the target sites were used for PCR to detect knockout of the target sequence.The PCR products were purified and ligated into the pMD-18T vector for sequencing.

Expression,purification,and antibody preparation of ZnF615 protein

TheZnF615open reading frame (ORF) (BGIBMGA007439)was cloned using cDNA fromB.moriembryos with the primers shown in Supplementary Table S9.The clonedZnF615cDNA was inserted into the pGEX-6P-1 vector with a GST tag at the N-terminus to generate an expression vector,which was then used to transformEscherichiacoli(BL21) cells for protein expression.The recombinant protein was purified using a GST Protein Purification Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Beyotime,China) (Supplementary Figure S1).The purified recombinant GST-ZnF615 protein was mixed with Freund’s adjuvant (Dingguo Biotechnology,China) and injected into BALB/c mice obtained from the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (China).Antisera were collected after three booster injections,each with 100 μg of the recombinant protein.

Analysis of DNA affinity purification sequencing (DAPseq)

DAP-seq was carried out using recombinant ZnF615 proteins.Genomic DNA extracted from silkworm embryos was sonicated to obtain fragments (~200 bp).The fragments were purified,end repaired,and ligated with Y-shaped adaptors,as described previously (Bartlett et al.,2017),to generate a sequencing library for DAP-seq experiments.The ZnF615 ORF was inserted into the pFN19K-HALO plasmid to introduce a HaloTag at the N-terminus of the protein.The plasmid was transcribed and translatedinvitrousing TnT?SP6 High-Yield Wheat Germ Master Mix (Promega,USA).The subsequent steps were performed by Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co.(China) following standard DAP-seq protocols (Bartlett et al.,2017).

The DAP-seq reads were mapped to theB.morireference genome (Wang et al.,2005;Xia et al.,2004) using Bowtie2(v2.2.5) (Langmead &Salzberg,2012).All reads from the interval,2 kb region upstream of the transcriptional start site(TSS),and 2 kb region downstream of the transcriptional termination site (TTS) were counted using deepTools (v3.2.0)(Ramírez et al.,2016).MACS2 (v2.1.2) (Zhang et al.,2008)was used to identify read-enriched regions from the DAP-seq data.Dynamic Poisson distribution was used to calculate theP-value of the specific region based on the unique mapped reads.The region was defined as a peak when theq-value was <0.05.Peak-related genes were annotated using the ChIPseeker package in R (Yu et al.,2015).Based on genomic location and gene annotation information of the peaks in theB.morireference genome,peak-related genes and their distributions in different regions (e.g.,intergenic,intron,downstream,upstream,and exon regions) were identified.MEME (v5.4.1) (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) and DREME (v5.4.1) (http://memesuite.org/tools/dreme) were used to detect specific motifs.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (TaKaRa,Dalian,China),and cDNA was synthesized using a First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa,Dalian,China).QRT-PCR was performed using a 2×SYBR PremixEXTaqTMKit (TaKaRa,China).Relative gene expression level was calculated using the 2???Ctmethod (Livak &Schmittgen,2001).Data were normalized to the housekeeping gene ribosomal protein 49(Rp49).All data represent three biological replicates and three technical repeats.

Construction of luciferase vector

Genomic DNA was extracted from theB.moriembryos.The promoter of theactingene,including the 365 bp core promoter and 63 bp 5' untranslated region (UTR),was cloned into the pMD-18T vector (TaKaRa,Dalian,China).The promoter and gene body of theZnF615gene were amplified by PCR and then cloned into the luciferase reporter vector pGL3-basic(Promega,USA).

RNA interference (RNAi)

For RNAi in theB.moriembryos,a 200–600 bp unique fragment of the target gene ORF was chosen as the template for the synthesis of gene-specific double-stranded RNA(dsRNA) using the T7 RiboMAXTMExpress RNAi System(Promega,USA).The synthesized dsRNA (20–50 ng) was injected into embryos within 2 h of oviposition using a micromanipulator,as described previously (Xu et al.,2022b).Three replicates consisting of 300–400 embryos per replicate were carried out.To evaluate knockdown efficiency,qRT-PCR was performed using the specific primers.

Analysis of egg number and hatch rate

To record egg number,ovaries were dissected from wild-type(WT),Dnmt1-/-,andZnF615-/-B.morimoths daily from the first to eighth day of the pupal stage,and the eggs in the dissected ovaries were collected and counted.

The larvae hatched from the eggs were recorded on days 6–10.5 after oviposition.The hatch rate was calculated as:hatch rate=number of larvae/number of eggs.

Statistical analysis

For all measurements,data are presented as the mean±standard error (SE).P-values for group comparisons were calculated using a paired Student’st-test (*:P<0.05;**:P<0.01;***:P<0.001).

RESULTS

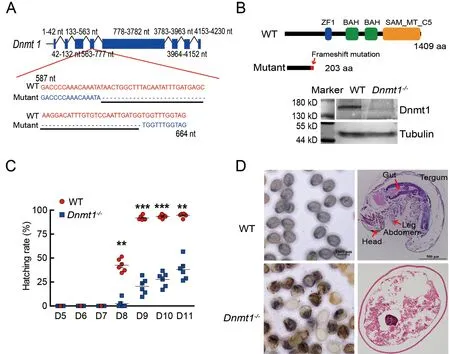

Dnmt1 knockout suppresses embryogenesis

Previous research has shown thatDnmt1knockdown by RNAi impacts embryonic development inB.mori(Xiang et al.,2013;Xu et al.,2021).To confirm this result,CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing was applied to knockout theDnmt1gene.First,sgRNAs targetingDnmt1exon 4 were injected intoB.moriembryos within 2 h of oviposition.The knockout mutants were detected by aligning the edited target sequences to the WT genomic sequences.One mutant showed a deletion of 52 bases inDnmt1exon 4 (Figure 1A),resulting in a defective protein of only 203 amino acids without functional domains,significantly different from the complete Dnmt1 protein of 1 409 amino acids (Figure 1B).The hatching rate in theDnmt1-/-group was only 38.09%,a decrease of 57.66% from the WT group,which had a 95.75% hatching rate at days 10–11 (Figure 1C).Western blot analysis showed that bothDnmt1-/-hatched andDnmt1-/-unhatched embryos lacked a complete Dnmt1 protein (Supplementary Figure S2).At day 8 post-oviposition,defects in the unhatchedDnmt1-/-embryos were found,whereas the WT embryos had developed and started to hatch.The head,thorax,abdomen,gut,and leg segments of the mutant were underdeveloped,suggesting that early development was affected byDnmtknockout(Figure 1D).Ovarian development was also altered in theDnmt1+/-heterozygotes compared to the WT.The egg number generated byDnmt1+/-decreased by approximately 20%compared to the WT (Supplementary Figure S3).These results indicate that DNA methylation catalyzed by Dnmt1 has a considerable influence on ovarian development and early embryogenesis.

Figure 1 Effect of Dnmt1 knockout on embryonic development and egg hatching in B.mori

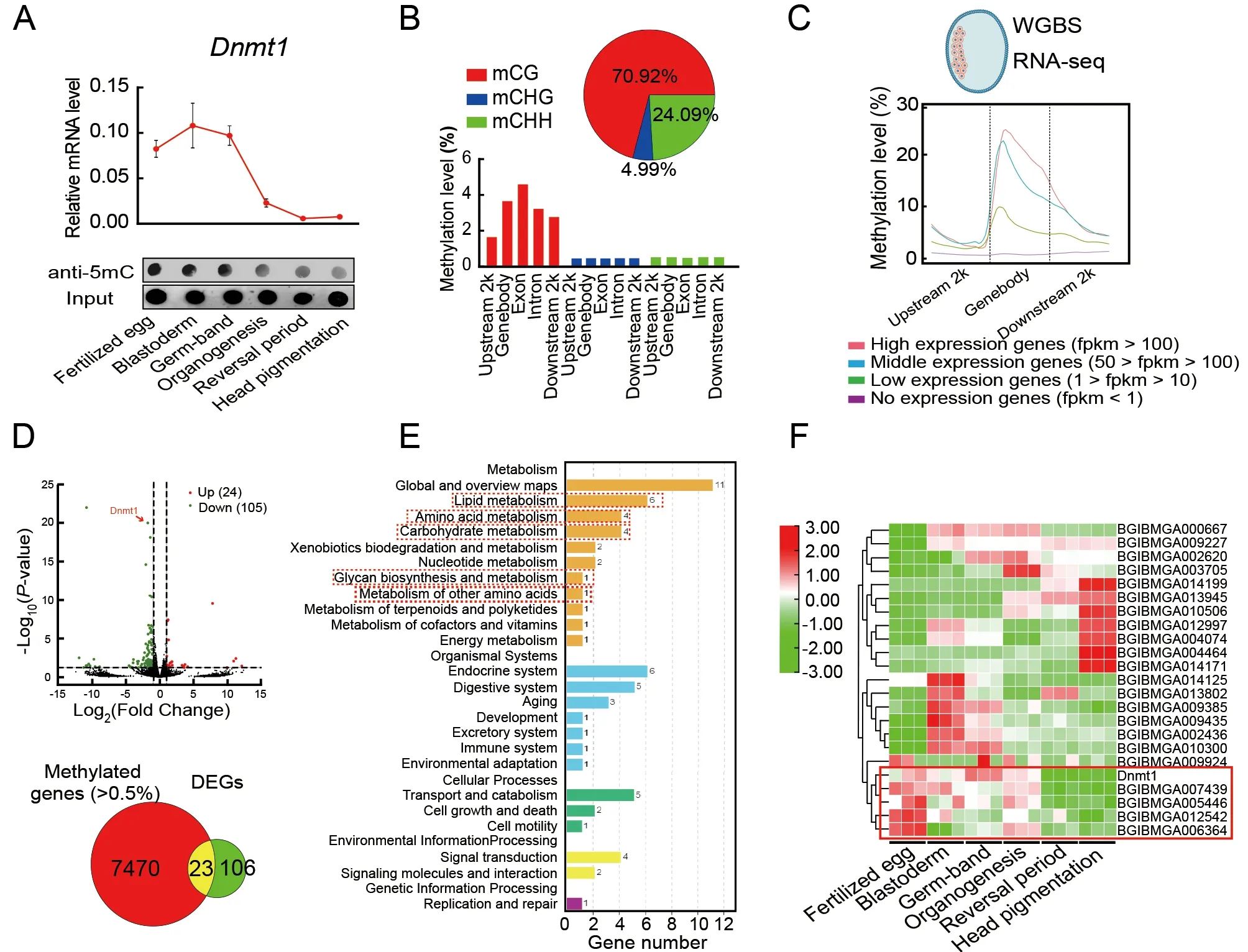

Identification of DNA-methylated genes required for embryogenesis

To study how DNA methylation affects embryonic development,5mC levels in embryos at different developmental stages were examined by qRT-PCR and dot blot analysis.Results showed that 5mC was detectable throughout embryonic development but was higher during the early embryonic stages (i.e.,fertilized egg,blastoderm,and germ-band) than during the late embryonic stages (i.e.,organogenesis,reversal period,and head pigmentation)(Figure 2A).Illumina WGBS of genomic DNA from blastoderm-stage embryos,when the highestDnmt1mRNA level was detected (Figure 2A),showed a total of 439 751 5mCs in the whole genome,representing 0.67% of all cytosine sites in theB.morigenome (Figure 2B;Supplementary Table S1).CG methylation (70.92%) was higher than CHG (4.99%)and CHH (24.09%) methylation (H represents A,C,or T).CG,CHG,and CHH methylation occurred at 1.34%,0.44%,and 0.50% of the genome-wide CG,CHG,and CHH sites,respectively.In the CG context,DNA methylation occurred predominantly in gene bodies,particularly in the exons(Figure 2B).Gene annotation showed that the methylated genes were mainly enriched in pathways related to protein metabolism,including ribosome,ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes,proteasome,aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis,protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum (ER),ubiquitinmediated proteolysis,and protein export (Supplementary Figure S4).In addition,four groups of genes were identified according to mean expression levels.The relationship between the expression levels of these genes and DNA methylation rates was analyzed (Figure 2C).Most methylation changes in the genes occurred around the TSSs.The gene expression levels were positively correlated with the methylation rates (Figure 2C),suggesting that the methylated protein metabolism-related genes were expressed at high levels,whereas unmethylated genes were expressed at low levels.

To further investigate the transcription products of the target genes of DNA methylation,RNA-seq was implemented afterDnmt1RNAi.The fertilized zygotes were injected withdsgfp(control) ordsDnmt1and collected after 48 h to evaluate RNAi efficiency and conduct RNA-seq.TheDnmt1mRNA level was significantly decreased by RNAi (Supplementary Figure S5).Transcriptome data showed that 24 up-regulated genes and 105 down-regulated genes were identified between theDnmt1RNAi treatment and control (Figure 2D;Supplementary Table S2).Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were mainly enriched in nutrient metabolic pathways,including lipid,amino acid,and carbohydrate metabolism (Figure 2E).Among the 129 DEGs,23 had a methylation rate of more than 0.5%(Figure 2D),which may be positively correlated with the mRNA level.Among these 23 DEGs,the mCpG sites of 20 genes were enriched around their TSSs (Supplementary Figure S6 and Table S3).To investigate whetherDnmt1RNAi affects embryogenesis through these 23 genes,their expression patterns were compared with that ofDnmt1from the fertilized egg to head pigmentation stages of embryonic development via the transcriptome (Xu et al.,2022a).Four genes (BGIBMGA007439,BGIBMGA005446,BGIBMGA012542,andBGIBMGA006364) were found to have identical expression patterns toDnmt1(Figure 2F;Supplementary Table S4),implying that they may be positively regulated by DNA methylation.Therefore,these four genes were selected as target genes ofDnmt1for further study.

Figure 2 Identification of DNA methylation-modified genes affecting embryonic development in B.mori

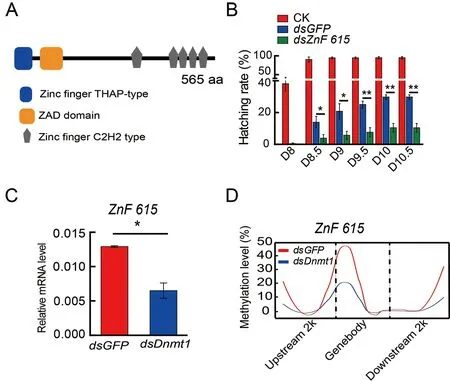

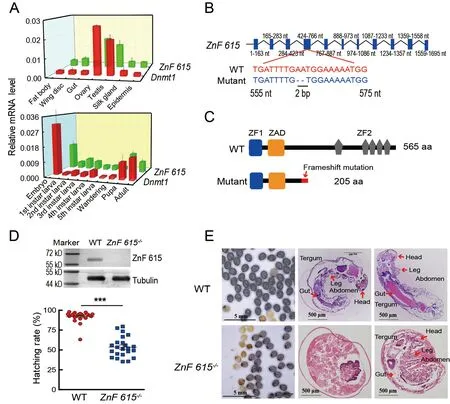

To determine the roles of these candidate genes in embryogenesis,dsRNA targetingBGIBMGA007439,BGIBMGA005446,BGIBMGA012542,andBGIBMGA006364was injected into eggs on the first day of oviposition(Supplementary Figure S7).Knockdown of theBGIBMGA007439gene,corresponding to the zinc finger protein ZnF615 containing six zinc finger motifs and a zinc finger associated domain (Figure 3A),significantly reduced the hatching rate (Figure 3B),whereas RNAi of the other three candidate genes did not have an obvious effect on hatching(Supplementary Figure S8).Furthermore,the mRNA(Figure 3C) and methylation levels (Figure 3D) of the promoter and gene body ofZnF615were significantly decreased afterDnmt1RNAi,indicating thatZnF615is downstream ofDnmt1and involved in embryogenesis.

Figure 3 DNA methylation of ZnF615 by Dnmt1 affects B.mori embryonic development

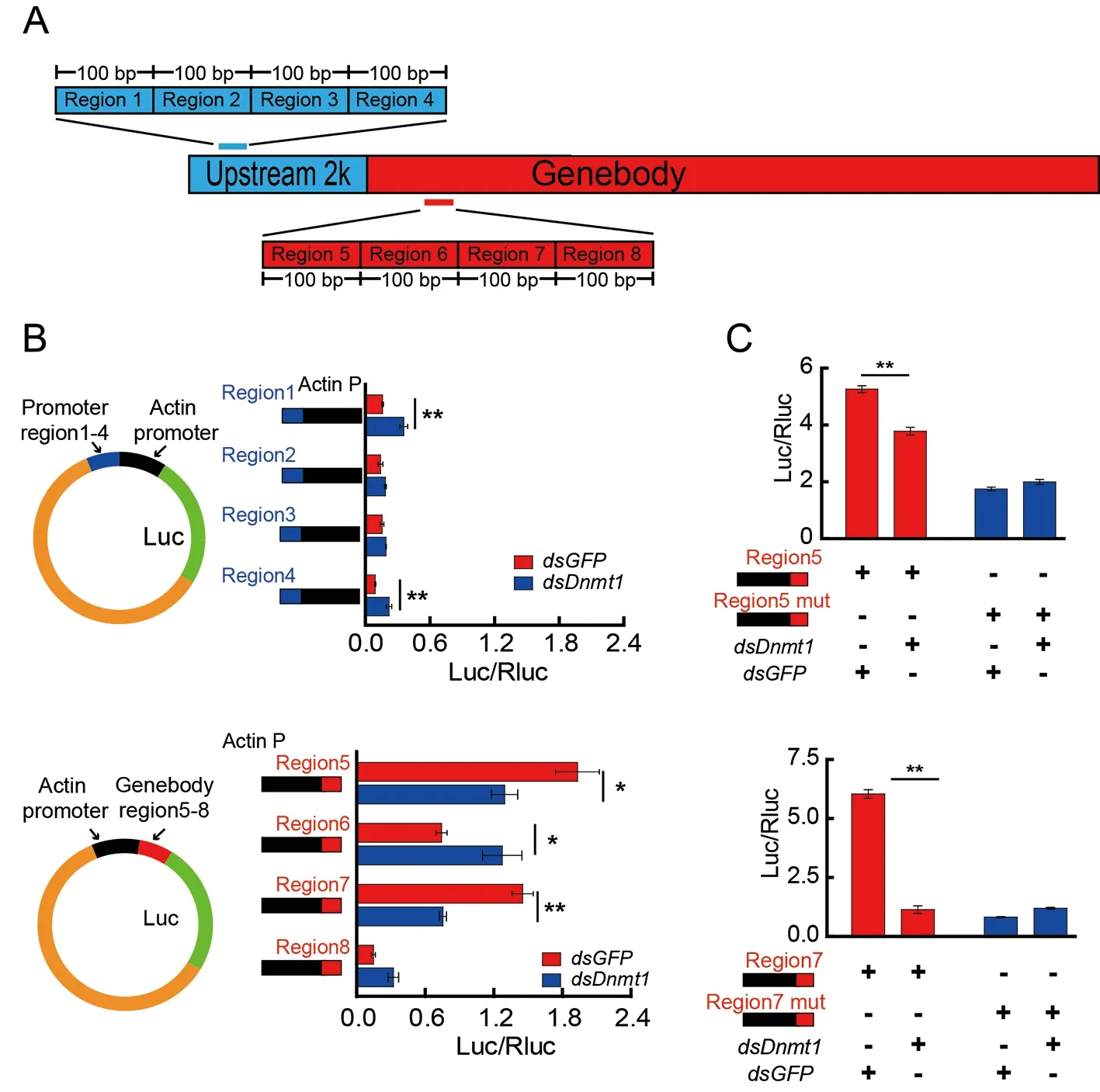

DNA methylation in ZnF615 gene body enhances its expression

To investigate how 5mCG is involved inZnF615expression,eight 100 bp regions that showed the largest differences in mCG levels in the promoter (regions 1–4) or gene body(regions 5–8) ofZnF615afterDnmt1RNAi were selected and analyzed to determine their regulatory activities using a luciferase assay (Figure 4A;Supplementary Figure S9).The transcriptional activity of the luciferase reporter under the control of the individual regions fused with the core promoter of theactingene was tested inBm12 cells withDnmt1RNAi(Supplementary Table S5).The transcriptional activities of regions 5 and 7 in the gene body were significantly inhibited byDnmt1RNAi,whereas that of region 6 was enhanced.The transcriptional activities of regions 1 and 4 in the promoter were also regulated byDnmt1RNAi,but activity was extremely low (Figure 4B).Mutations in regions 5 and 7,in which CG at the mCpG sites was replaced by AT(Supplementary Figure S9),did not cause any change in transcriptional activity afterDnmt1RNAi (Figure 4C).Thus,we assume that 5mC in the gene body rather than in the promoter of theZnF615gene is primarily responsible for regulation of gene expression.These results indicate that methylation in regions 5 and 7 in the gene body enhancesZnF615gene expression,which offsets the inhibitory effect of region 6 during embryogenesis in silkworms.

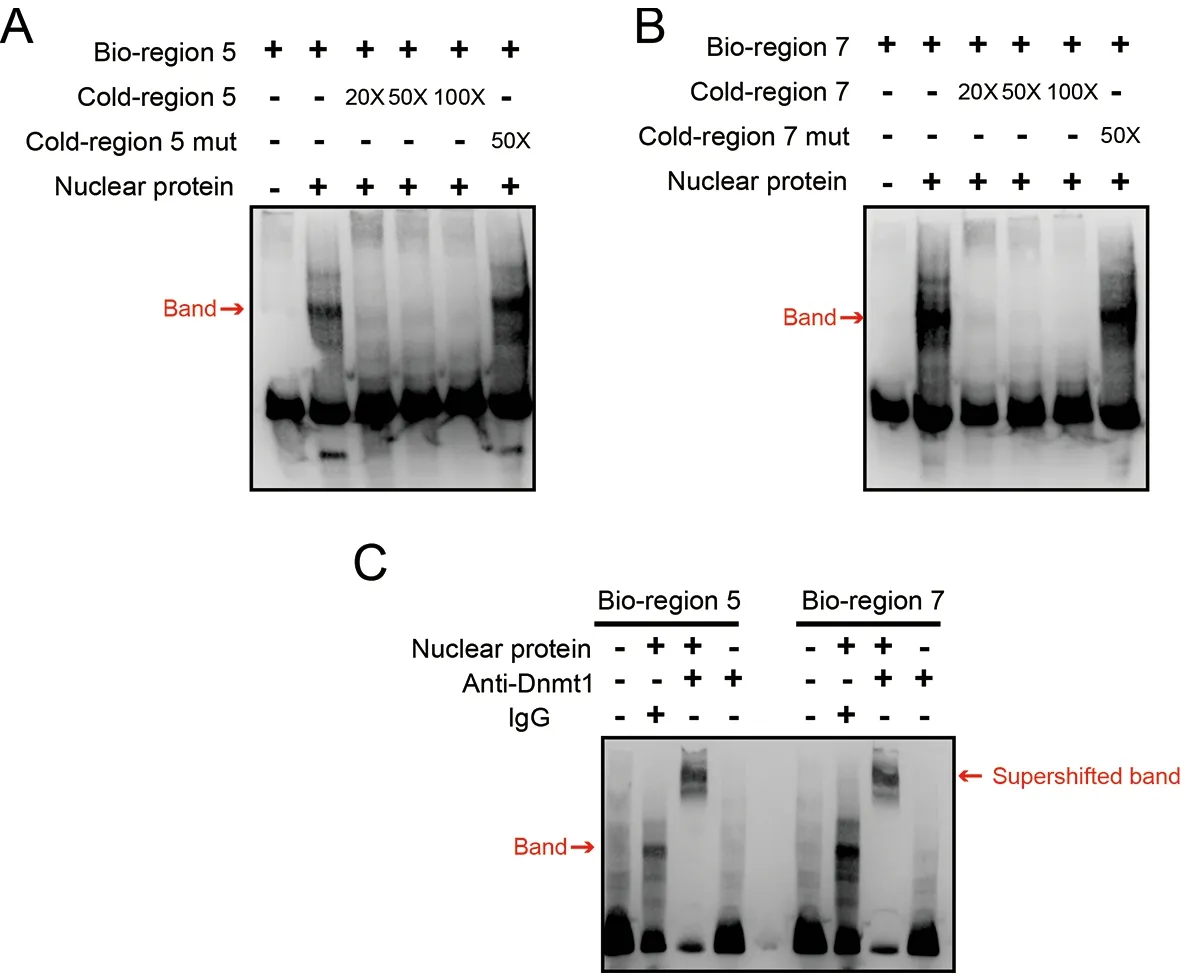

To confirm whetherDnmt1directly binds to regions 5 and 7 in the gene body,thereby catalyzing the formation of mCG,EMSA was conducted with the biotin-labeled region 5 or 7 probes and nuclear proteins isolated from silkworm embryos(Figure 5).Nuclear proteins bound to labeled region 5 or 7 probes could be competed off with 50× or 100× nonlabeled probes (cold probe) but not with mutated nonlabeled probes(Figure 5A,B).To confirm whether the binding protein is Dnmt1,a supershift assay was performed using an anti-Dnmt1 antibody (Xu et al.,2021).A supershifted band was detected when the anti-Dnmt1 antibody was present (Figure 5C),suggesting that the protein bound to the of region 5 or 7 probes was Dnmt1.Thus,the transcriptional activity assay and EMSA results demonstrated that DNA methylation catalyzed by Dnmt1 in gene body regions promotedZnF615expression.

Knockout of ZnF615 suppresses embryogenesis

To confirm the function ofZnF615in embryogenesis,CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing was applied to knockout theZnF615gene.The qRT-PCR results showed thatDnmt1andZnF615had similar expression patterns,with higher mRNA levels in embryos and gonads at the pupal stages in the WT silkworms (Figure 6A).AZnF615mutant,in which two bases in exon 4 were deleted (Figure 6B),formed a defective protein of 205 amino acids,lacking five of the zinc finger motifs in the complete protein of 565 amino acids (Figure 6C),and the fulllength ZnF615 protein could barely be detected inZnF615-/-(Figure 6D top).The hatching rate in the homozygousZnF615-/-mutant was similar to that in theDnmt1-/-mutant (Figure 6D bottom),and the embryos were unable to develop normally,with only 53.54% of the eggs hatching (Figure 6D bottom).Similar toDnmt1-/-B.mori,bothZnF615-/-hatched andZnF615-/-unhatched embryos lacked the complete ZnF615 protein (Supplementary Figure S10).

Paraffin sections ofZnF615-/-mutant embryos at day 8 postoviposition revealed that the unhatchedZnF615-/-embryos did not undergo complete embryogenesis and the organs were undifferentiated and unformed at the early stage (Figure 6E).Some of the hatchedZnF615-/-silkworms also died during the larval period,although about 30% survived to adulthood(Figure 6E).However,theZnF615+/-embryos hatched and developed normally (Supplementary Figure S11).This phenotype was similar to that of theDnmt1-/-mutant.In addition to the low hatching rate,egg number in theZnF615-/-mutant decreased by approximately 20% compared to the WT(Supplementary Figure S12).

Figure 4 Effect of DNA methylation in promoter and gene body on transcription of ZnF615 gene

Identification of genes required for embryogenesis regulated by DNA methylation-mediated ZnF615

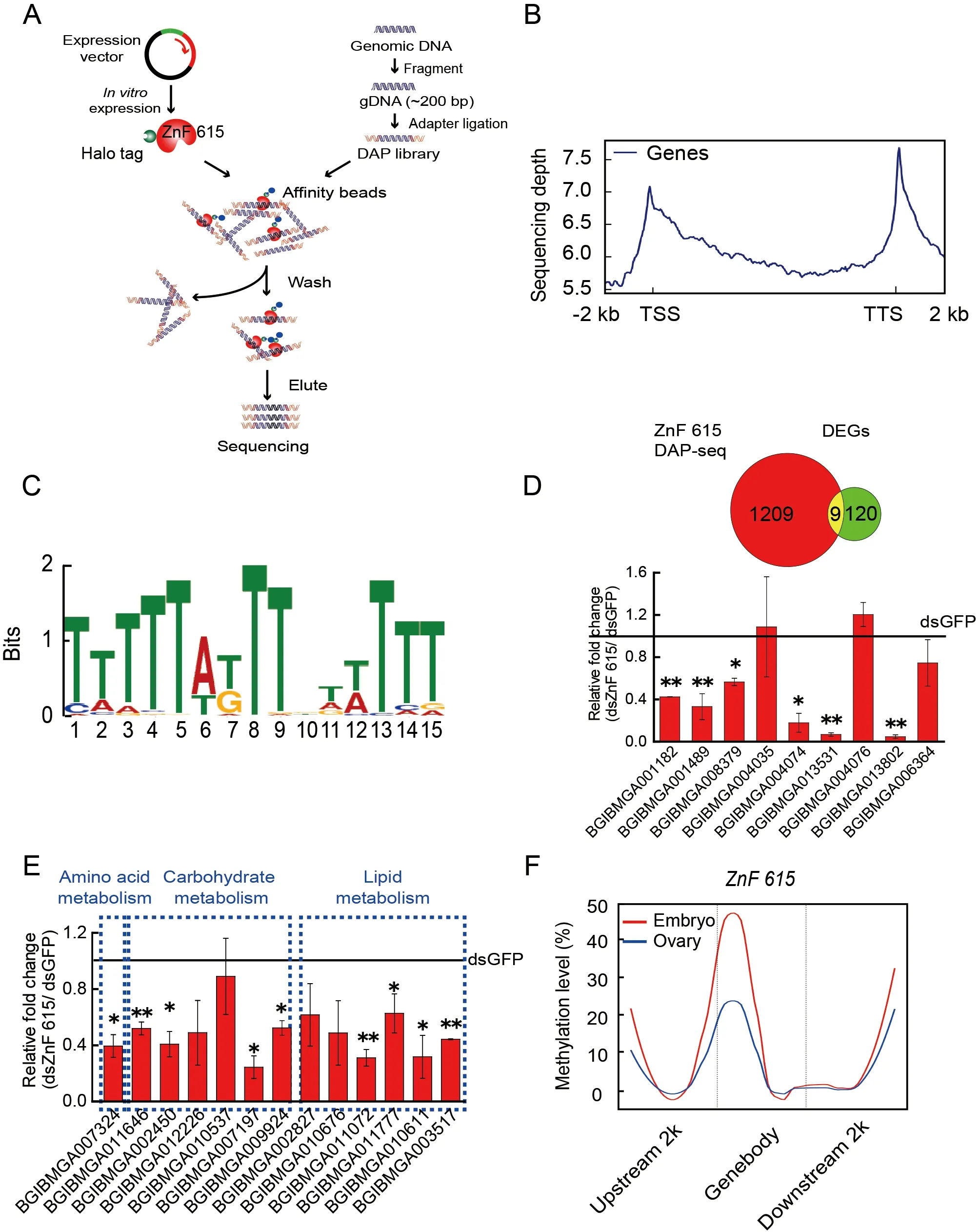

To determine which downstream target genes are regulated by ZnF615,DAP-seq analysis was carried out.Immunofluorescence assays showed that the ZnF615 protein was localized to the nucleus ofBm12 cells (Supplementary Figure S13),implying that it is a nuclear factor acting on its target genes.Therefore,we used DAP-seq to identify the target genes acted upon byZnF615in the silkworm genome(Figure 7A).By mapping the DAP-seq reads to theB.morigenome,ZnF615 binding sites and motifs were identified(Figure 7A).ZnF615 had binding sites on each scaffold,especially high peak number regions on Ps01–06(Supplementary Figure S14).The ZnF615 binding sites were enriched in the regions near the TSS and TTS (Figure 7B).The most frequently appearing sequence motif was TTTTTATTTGTTTTT (Figure 7C),suggesting that this may be the specific motif for ZnF615 binding.A total of 1 209 ZnF615 candidate binding genes were annotated (Supplementary Table S6).To further investigate the genes regulated by DNA methylation-mediated ZnF615,we combined the ZnF615 peak-related genes from DAP-seq and DEGs identified by RNA-seq afterDnmt1RNAi (Figure 7D).Nine DEGs afterDnmt1RNAi were enriched in ZnF615 DAP-seq(Supplementary Table S7).The mRNA levels of these nine genes were determined by qRT-PCR afterZnF615RNAi,with six showing significant reductions (Figure 7D),i.e.,adhesive plaque matrix protein,synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2B,uncharacterized protein LOC101738308,cuticular protein glycine-rich 19,obscurin,and AGAP005312-PA-like protein(Supplementary Figure S15).These findings suggest that the genes directly bound by ZnF615 and down-regulated byDnmt1RNAi are not nutrient metabolism-related genes.Therefore,in theZnF615-knockdown embryos,we detected changes in the expression of nutrient metabolism-related DEGs enriched afterDnmt1RNAi,including amino acid,carbohydrate,and lipid metabolism pathways (Figure 7E;Supplementary Table S8).The qRT-PCR results showed that nine of the 13 nutrient metabolism-related genes enriched byDnmt1RNAi were significantly decreased afterZnF615RNAi(Figure 7E),including lipase,glucose dehydrogenase,and glucosidase metabolism-related genes.These results indicate that DNA methylation may enhance the expression of these genes via its effects on ZnF615.

Figure 5 EMSA analysis of Dnmt1 binding with regions 5 and 7 in ZnF615 gene body

As Dnmt1-mediated ZnF615 methylation affects the development of embryos and ovaries,we further investigated whether ZnF615 is methylated at the same sites and at the same level in the ovary and embryo.Analysis showed that the methylation regions in theZnF615gene were similar between the ovary and embryo,but the methylation level of theZnF615gene in the embryos was twice that in the ovaries (Figure 7F)(Xu et al.,2021).These observations suggest that DNA methylation of theZnF615gene is involved in the regulation of early embryogenesis inB.moriand that modification ofZnF615methylation in the embryos likely originates in the ovaries and is strengthened byDnmt1activity during embryogenesis.

DISCUSSION

Properly regulated gene expression is essential for embryonic development.InB.mori,the fertilized zygote progresses through the blastoderm,germ-band,organogenesis,reversal period,and head pigmentation stages to develop into a mature embryo.Many genes related to DNA replication,transcription,protein synthesis,and epigenetic modifications are up-regulated before embryonic organogenesis,while genes related to hormone synthesis and signaling,neuropeptides,and cuticle proteins are up-regulated at or after the organogenesis stage (Xu et al.,2022a).Thus,DNA methylation modifications may regulate early embryonic development by influencing the expression of genes necessary for cell division and differentiation.DNA methylation is associated with embryonic development in hemimetabolous and holometabolous insects (Bewick et al.,2019;Li et al.,2020;Ventós-Alfonso et al.,2020;Xiang et al.,2013).However,how DNA methylation affects insect embryonic development remains unclear.In this study,we confirmed the critical role of DNA methylation inB.moriembryogenesis byDnmt1knockout (Figure 1).We found that DNA methylation level was higher in early embryogenesis than in later embryogenesis (Figures 1,2A).Based on genome-wide methylation analysis in early embryos,we also found that 5mC methylation mainly occurred in the gene bodies of highly expressed protein metabolism-related genes (Figure 2C;Supplementary Figure S4) required for early embryonic development.We determined that the nuclear protein ZnF615 gene was downstream ofDnmt1(Figure 3).Finally,we revealed that the expression of nutrient metabolism-related genes was inhibited byDnmt1andZnF615RNAi (Figures 2E,7D,E).Based on these findings,we hypothesize that downstream genes regulated by Dnmt1-inducedZnF615methylation are vital for earlyB.moriembryonic development.

Research has reported that 5mC affects early embryonic development in insects.InTriboliumcastaneum,DNA methylation occurs in the early stage of embryogenesis,followed by global demethylation as the embryo develops(Feliciello et al.,2013).Dnmt1RNAi inB.germanica,which has bothDnmt1andDnmt3,results in defective embryos(Ventós-Alfonso et al.,2020).In this study,we demonstrated that knockout ofDnmt1,the only DNA methyltransferase inB.mori,stopped early embryonic development and even induced death (Figure 1),similar to that ofDnmt1RNAi (Lyu et al.,2021;Xiang et al.,2013;Xu et al.,2021).However,nearly 40% of the homozygous knockout mutants hatched and grew normally.We speculate that the defective Dnmt1 protein in the knockout mutant was still partially active after mutation,or the organism was able to activate other mechanisms to compensate for the damage caused by the lack of DNA methylation.These results highlight the necessity ofDnmt1expression and DNA methylation in early embryogenesis to ensure proper embryonic development in insects (Figure 1).

Figure 6 Loss-of-function analysis of ZnF615 in B.mori embryos

Importantly,in this study,we identified and characterized the nuclear protein geneZnF615,which is modified by 5mC and acts downstream ofDnmt1.Here,ZnF615knockout resulted in embryo and ovary phenotypes similar to those ofDnmt1(Figure 6);moreover,70% of the nutrient metabolismrelated genes down-regulated byDnmt1RNAi were regulated byZnF615(Figure 7E;Supplementary Table S8),including lipid,amino acid,carbohydrate,and glycan metabolismrelated pathways.Early embryonic development requires glycosidases to hydrolyze carbohydrates to produce glucose and provide energy;amino acids and fatty acids are also important for insect embryonic development (Levin et al.,2017).Knockdown of pancreatic lipase-related protein 2 inNilaparvatalugensresults in a decrease in the hatching rate(Xu et al.,2017).Thus,Dnmt1RNAi may impact insect development by affecting these few genes.Dnmt1RNAi inhibitedZnF615expression,leading to the down-regulation of genes required for embryogenesis.BombyxmoriZnF615 is a typical C2H2 zinc finger protein;C2H2 zinc fingers comprise the most common and diverse family of transcription factors(Vaquerizas et al.,2009;Weirauch &Hughes,2011;Wu et al.,2019).However,as the defective ZnF615 protein in knockout mutants contained a zinc finger motif and zinc finger associated domain and may be partially active,more than 50% of mutant embryos hatched normally.

Figure 7 DAP-seq analysis of ZnF615 in B.mori embryos

In insects,5mC occurs in genes with conserved housekeeping functions (Bonasio et al.,2012;Lyko et al.,2010;Sarda et al.,2012;Simola et al.,2013).Our WGBS and RNA-seq data revealed a positive correlation between high methylation rates and high expression levels of numerous housekeeping genes (Figure 2C;Supplementary Figure S4).However,Dnmt1RNAi did not down-regulate these housekeeping genes,as reported in other insects.For example,suppression of DNA methylation byDnmt1RNAi inOncopeltusfasciatus(Bewick et al.,2019) or by 5mC inhibitor treatment inB.mori(Xu et al.,2021) only down-regulates a small number of genes but has a significant impact on insect development.We previously speculated that highly expressed housekeeping genes may be regulated by multiple pathways or mechanisms,including DNA methylation (Xu et al.,2021).Therefore,the transcriptional inhibition caused by the loss of gene body methylation may be easily compensated by other regulatory pathways.Second,the transient loss of methylation caused byDnmt1RNAi did not change the chromosomal structure of these genes,resulting in no change in gene expression.

In insects,5mC usually occurs in the gene bodies of highly transcribed genes (Glastad et al.,2014;Wang et al.,2013;Xiang et al.,2010;Zemach et al.,2010) and does not inhibit transcription but leads to gene activation (Hellman &Chess,2007;Meng et al.,2015;Wolf et al.,1984).This may occur because DNA methylation shapes chromatin and gene expression status by affecting the structure of nucleosomes and/or regulating other factors (Chodavarapu et al.,2010).In addition,methyl-CpG-binding proteins (MeCPs and MBDs)specifically recognize DNA methylation and change the local chromatin structure by recruiting histone-modifying enzymes or chromatin-remodeling complexes (Meng et al.,2015).Gene body methylation can also facilitate transcription elongation by inhibiting the activation of alternative promoters and controlling alternative splicing (Meng et al.,2015).In theB.moriovaries,5mC in the 5' regions of the gene bodies recruits acetyltransferase through MBD2/3 to enhance gene expression (Xu et al.,2021).Thus,consistent mechanisms of methylation targeting gene bodies (i.e.,intragenic methylation)of protein metabolism-related genes may facilitate and promote embryogenesis.We demonstrated that Dnmt1 directly binds to the 5' region of theZnF615gene body,thereby promoting its transcription efficiency by catalyzing 5mC formation (Figures 4,5) and subsequent transcription of theZnF615gene.

We found similar intragenic methylation enrichment in genes associated with protein metabolism-related pathways in theB.moriovary (Xu et al.,2021) and embryo(Supplementary Figure S4).Furthermore,5mC-modifiedZnF615affected both ovarian and embryonic development by directly binding to protein metabolism-related genes and by indirectly regulating nutrient metabolism-related genes(Figures 2E,7E;Supplementary Figure S4).The effect of 5mC-mediatedZnF615in ovarian and embryonic development was achieved through DNA methylation at the sameZnF615gene sites (Figure 7G).We revealed that,in insects,intragenic DNA methylation in the ovary can be inherited by the fertilized egg.In addition,the higher methylation levels ofZnF615in the embryos than in the ovaries (Figure 7G) may explain why Dnmt1 expression is upregulated at the beginning of embryogenesis (Lyu et al.,2021).The up-regulation of DNA methylation inZnF615enhanced its own expression and that of its downstream genes.Thus,the similar methylation patterns and levels in the ovary and embryo ensured the expression of embryogenesisrelated genes.

In summary,this study demonstrated that intragenic DNA methylation enhances the expression of protein metabolismrelated and nutrient metabolism-related genes through the DNA methyltransferaseDnmt1and transcription factorZnF615to ensure ovarian and embryonic development,which may facilitate high fecundity in insects.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The raw Illumina sequencing data from WGBS of theB.moriearly embryos were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession No.SRP343081,in GSA database under accession No.CRA006748 and in Science Data Bank under DOI:10.57760/sciencedb.02099.The raw Illumina sequencing data from RNA-seq afterDnmt1RNAi inB.moriembryos were deposited in the NCBI SRA under accession No.SRP342894,in GSA database under accession No.CRA006752 and in Science Data Bank under DOI:10.57760/sciencedb.02111.The raw Illumina sequencing data from DAP-seq were deposited in the NCBI SRA under accession No.SRP342920,in GSA database under accession No.CRA006730 and in Science Data Bank under DOI:10.57760/sciencedb.02110.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data to this article can be found online.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

G.F.X.conducted most of the experiments,participated in data analyses,and drafted the manuscript.C.C.G.,Y.L.T.,T.Y.F.,and Y.L.P.conductedDnmt1andZnF615knockout,egg number and hatch rate analysis,RNAi,gene cloning,and protein expression analysis.H.L.,Y.G.L.,and C.M.T.assisted with the experiments and insect rearing.Q.L.F.and Q.S.S.provided technical and material support,participated in discussions,and helped draft and revise the manuscript.S.C.Z.conceived the study design,supervised the study,and drafted and finalized the manuscript.All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Professor Xiao-Qiang Yu and Associate Professor Liu Lin at South China Normal University,Guangzhou,China,for helpful discussions and comments on the article.

- Zoological Research的其它文章

- Zoological Research call for papers of Cavefish Special Issue

- Fuel source shift or cost reduction:Context-dependent adaptation strategies in closely related Neodon fuscus and Lasiopodomys brandtii against hypoxia

- Ecological study of cave nectar bats reveals low risk of direct transmission of bat viruses to humans

- Population and conservation status of a transboundary group of black snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus strykeri) between China and Myanmar

- Nucleus accumbens-linked executive control networks mediating reversal learning in tree shrew brain

- Europe vs.China:Pholcus (Araneae,Pholcidae) from Yanshan-Taihang Mountains confirms uneven distribution of spiders in Eurasia