Russia-Ukraine Conflict Weakens A SEAN Economic Prospects

By Hu Yukun

Motorists queue at a gas station in Quezon City,Metro Manila,Philippines,on March 7,2022,a day before a huge price increase on petroleum products is implemented.(EZRA ACAYAN)

I fnot for the escalation of conflict between Russia and Ukraine,ASEAN countries would likely have enjoyed an even bigger boost in economic growth after COVID-19 restrictions eased.Now,they must grapple with extra uncertainty caused by a crisis over 8,000 kilometers away.

Energy Price Whirlpools

When Russia started its“special military operation”in Ukraine on February 24,the international community as a whole was more concerned than shocked.Even if regional security threats could be limited to a certain geographical scope,the economic impact would not.

Although it accounts for only around 3 percent of global GDP,Russia can always influence the world economy with its energy leverage.Immediately after Russian troops crossed the border and international sanctions were imposed,people in most countries began to complain about soaring oil and gas prices.

Trade data from the Atlas of Economic Complexity indicate that ASEAN countries might not need to worry:Only 5.7 percent of Singapore’s 2019 imported refined petroleum was from Russia,and only 3.3 percent of Thailand’s imported crude that year came from Russia.

But neither could completely evade the upward global price pressure,and the impact has gone beyond rising local energy prices.

In Indonesia,the government had to provide a substantial subsidy for both“Premium”gasoline (88 RON)and“Pertalite”gasoline (90 RON).Now,the latter sells at Rp 7,650(around US$0.53) per liter,almost half the local market price (Rp 14,250).As noted by Stella Kusumawardhani,the economic research lead at Tenggara Strategics,the subsidy for Pertalite will increase the state’s compensation costs by Rp 13.2 trillion (around US$920 million) per month.

“The state budget will be (heavily)burdened”beyond the pandemic and the capital relocation plan.

More seriously,the fuel price hike is changing the situation beyond bills people pay.From pressure on the power supply to inflation and the rising cost of trade,the domino effect could really disturb ASEAN countries longing for economic rebound.

Consumption and Export

Forty days after the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict,The Nikkei noted that the rally in oil prices was forcing companies to raise commodity prices in Southeast Asian countries.In the Philippines,the inflation rate was already at 3 percent in the first two months of 2022.Bloomberg recently reported the inflation rate across the ASEAN region to be at 10-year high.

“The multiplier (effect) of oil price inflation is about 0.4 (percentage points),which means that for every 10 percent increase in oil price,you will have about a 0.4 percent increase in inflation,”said James P.Villafuert,senior economist at the Asian Development Bank.

He estimated that the Philippines,where oil prices had increased by as much as 30 percent,could be hit with inflation of about 1.2 percent.

According to a survey jointly conducted by The Nikkei and Japan Center for Economic Research (JCER),34 economists are changing their opinions on the potential threats to ASEAN economies for the coming 12 months:Rather than the COVID shock,inflation is the top concern in Indonesia,while rising commodity prices are the top concern in Malaysia.

Dendi Ramdani,head of industry and regional research at Bank Mandiri,knows all too well that as prices increase,household purchasing power declines.And this certainly leads to further weakened consumer demand.

Disruption to supply chains was an immediate global concern when the conflict broke out between Russia and Ukraine,and ASEAN was no exception.

But the problems do not end there.Western economies have been hit harder by the prolonged international sanctions,which is certainly the bad news for Southeast Asia,a developing region with high dependence on exports.With both air and shipping freight rates skyrocketing,exports from the ASEAN region have been shrinking.

When the two drivers of economic development are crippled,so are macroeconomic prospects.JCER just made a 0.2 percent downward revision of its projection for the GDP growth of ASEAN-5 (Indonesia,Malaysia,the Philippines,Singapore and Thailand) in 2022 from 5.1 to 4.9 percent.

This slight adjustment clearly demonstrates how a regional conflict thousands of miles away could directly offset economic growth of a promising region.

Food Security

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine is undoubtedly threatening Europe’s comprehensive security,but Europe is not alone.For the ASEAN region,the insecurity may be more indirect,but just as serious.Instead of munitions,it’s all about food.

Russia and Ukraine account for 29 percent of global wheat exports,19 percent of the world corn supply,and 80 percent of world sunflower oil exports.Unlike energy,exports in these areas really matter to ASEAN countries if uncertainty continues to mount in the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

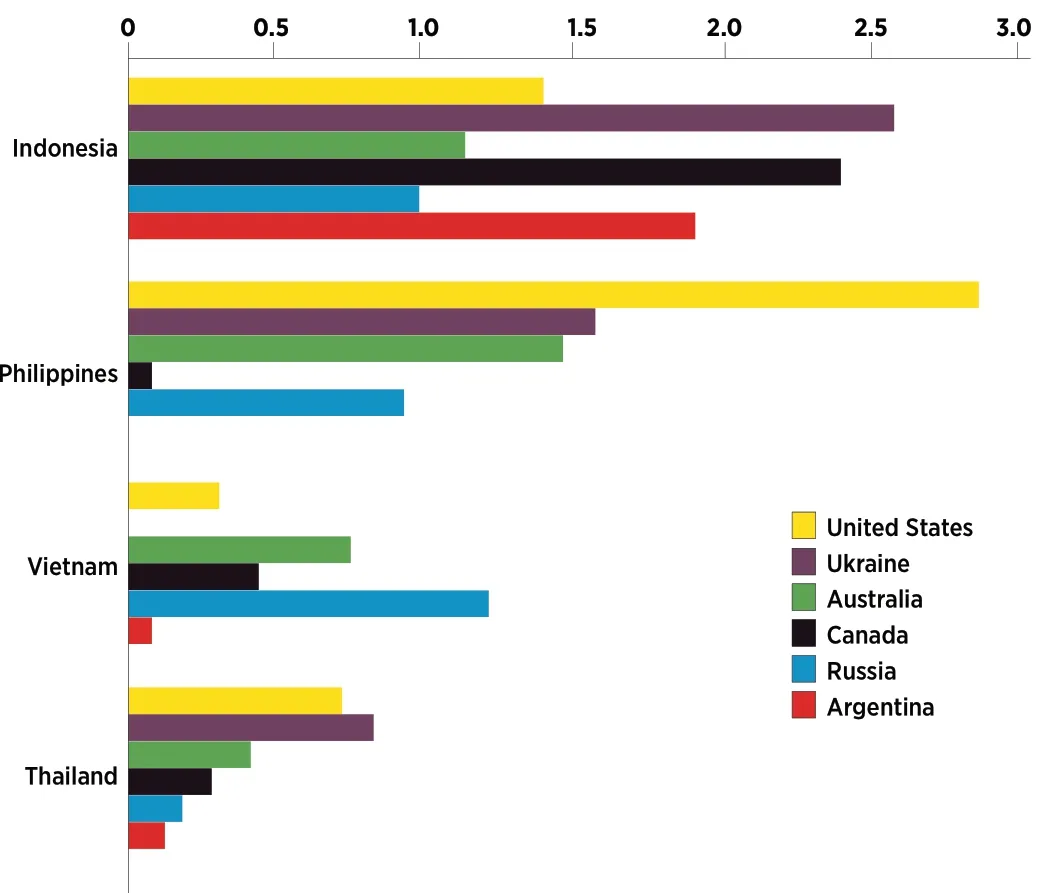

In 2019,the Philippines imported US$1.45 billion worth of wheat,nearly 16 percent of which came from Russia and Ukraine,and last year a third of Indonesia’s wheat imports were sourced from Ukraine.Many other countries in Southeast Asia are in similar positions at smaller scales from a statistical perspective.

“Wheat is the main ingredient in instant noodles,a staple in Indonesia,”Stella explained.“So far,we have not seen the price of instant noodles increase because we still have 1.2 tons of wheat,enough for the next two months.But if the conflict drags on,the price of instant noodles will rise within months.”

Even domestic food production is being affected.NPR (National Public Radio) reported that in some African countries such as Kenya and Nigeria,skyrocketing natural gas prices led to higher fertilizer costs,which is discouraging more and more farmers from growing food.

Top Southeast Asia Importers and Sources

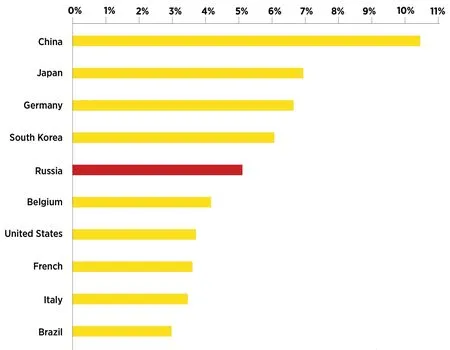

Top 10 Exporting Nations of Iron and Steel by Value

The same is happening with Indonesia,according to Stella.Soaring prices of wheat and raw materials for fertilizers are making both imports and domestic production in Indonesia more difficult.The archipelagic state needs to feed a population of over 270 million,and nearly half of its potassic fertilizer comes from Russia and Belarus.

The same story has also been seen in other ASEAN countries.Recently,the Atlantic Council expressed concern about the rising risk of hunger and civil unrest with wheat prices up over 60 percent.Food scarcity is likely to be a major security concern for the region if the status quo continues.

Manufacturing and Supply Chains

Disruption to supply chains was an immediate global concern when the conflict broke out between Russia and Ukraine,and ASEAN was no exception.The Diplomat soon predicted that manufacturing in ASEAN countries would likely take a hit.

Russia and Ukraine are major providers of semi-finished iron and steel,an important material for manufacturing cars,machinery,and electronics,which account for 7.5 percent of global exports.The Washington Post predicted steel would be“the other big commodity shock”from the conflict a month after it broke out.

And the ASEAN region’s reliance on imports from both countries is even heavier.

In 2019,21.4 percent of Thailand’s semi-finished steel was sourced from Russia and Ukraine.Indonesia got a quarter of its steel from one of the two,and the Philippines almost half.Despite maintaining output amid the February surge of the Omicron variant,raw material supply has been a key hindrance to manufacturing output even before the crisis in Ukraine.

Persistently growing demand for steel and iron has long been considered capacity pressure for the ASEAN region,and it could have a spiraling effect.Upward price pressure is being intensified by metal supply constraints,and soaring metal prices are discouraging and disturbing spending,which might further impede the manufacturing capacity.

But many believe that Southeast Asian supply chains will remain resilient and overcome the relatively short-term pain.Many other options for supply can be found in countries such as China,the United States,Japan,Germany,and other EU countries.

Higher prices are still expected for the near future,but they could be only moderate if ASEAN countries can endure some short-term pain.

Of course ties between ASEAN and the two far-off countries in many other areas could further complicate the impact on the region.Russia supplies arms to many countries in the region,facilitates financial transactions,and promotes joint ventures between Russian energy giants and major stateowned companies in countries like Indonesia,Malaysia,and Vietnam.

Such factors are why“it has been hard for Southeast Asian nations to take a hard stance against Russia,”in Stella’s words.

They may be uncertain,but the macro economic prospects of ASEAN are by no means gloomy.Ultimately,the economic ties between ASEAN and Russia/Ukraine are not very tight,and those could use more resilience through ability to blunt negative impact and more diverse approaches to promoting a vibrant economic recovery.