A Study of Idiom Translation in Bonsall’s The Red Chamber Dream

Hu Yun

Southwest Jiaotong University

Abstract: This paper combines quantitative and qualitative methods to analyze the translation characteristics of idioms in B. S. Bonsall’s full English translation of The Red Chamber Dream, starting from George Steiner’s fourfold hermeneutic motion: trust, aggression, incorporation, and restitution. Through data statistics and conclusion analysis, I concluded that the translation strategies of idioms in Bonsall’s English translation are mainly literal translations, supplemented by free translations, and literal translations combined with free translations, which also provides some enlightenment for the English translation of Chinese classics.

Keywords: idiom translation, Bonsall’s English full translation of The Red Chamber Dream, translation strategy and translation process, George Steiner’s fourfold hermeneutic motion theory

Idioms are the crystallization of people’s thoughts through long-term practice, and they are the brilliance and essence of a language. They are short and pithy, unique in content and form, and are a precious new force that constitutes the language appeal ofThe Red Chamber Dream. It is not an exaggeration to say that “one of the reasons for the great success ofThe Red Chamber Dreamin language art is the use of colorful idioms” (Han, 1986, p. 289). Since the spread ofThe Red Chamber Dreamoverseas, many translators have tried this translation task, translating it into 109 versions in 28 languages. Among them, the English editions include versions of selected passages, abridged and full versions. According to an investigation, Bonsall’s English translationThe Red Chamber Dream-Hung Lou Meng(Mêng) is the earliest full translation known to date and was published in the late 1950s (Wang et al., 2010, p. 195). Since it was published on the website of the main library of the University of Hong Kong in 2005 in the form of a scanned manuscript, more and more scholars have started related research. To create this first full English translation ofThe Red Chamber Dream, Bonsall had worked painstakingly for ten years. Truly a product of personal devotion to Chinese literature, the translation value needs to be further explored so that Bonsall’s love for China, Chinese language and literature, and hard work and unswerving dedication to the translation ofThe Red Chamber Dreamwill not be in vain, and this pioneering work will regain the academic value and significance that it deserves. In view of the particularity of idioms, we can have a glimpse of the translation strategies and processes in Bonsall’s complete English version through his idiom translations.

Since Bonsall’s full English translation ofThe Red Chamber Dreamwas published by the University of Hong Kong in 2005, various scholars have conducted relevant studies on its idiom translations. Duan Li selected 300 idioms fromThe Red Chamber Dreamand analyzed the idiom translations in Bonsall’s work; Hawkes’ and Yang Xianyi and Dai Naidie’s translations are based on the principle of “reality-cognition-language” of cognitive linguistics, and they summarized the characteristics of each translation. Based on the English corpus ofThe Red Chamber Dream, Liu Jing retrieved the corresponding translations of the first 56 idioms in Hawkes’ translation, Yang Xianyi’s translation, Joly’s translation and Bonsall’s translation, aiming at analyzing the similarities, differences, gains, and losses in dealing with the cultural information of idioms in the four versions, and summarizing the regular strategies and reasons of cultural reproduction in the four versions. Tan Mengna chose Bonsall’s translation and Joly’s translation to prove that the translations produced in different historical backgrounds must have their own specific historicity based on the basic theory of hermeneutics and through the study of idioms inThe Red Chamber Dreamtranslated by two translators in different historical periods.

The above research on idiom translation mainly focuses on the comparative study of parallel translation versions and summarizes the characteristics of different versions through comparison. However, the research on idiom translation in Bonsall’s version is still lacking. In view of this, this paper decided to analyze the translation process and translation strategies of idioms in Bonsall’s English full translation ofThe Red Chamber Dreamfrom the perspective of George Steiner’s fourfold hermeneutic motion, combining qualitative and quantitative methods.

Looking at the Idiom Translation in The Red Chamber Dream from the Perspective of George Steiner’s Fourfold Hermeneutic Motion Theory

There are countless links between translation and explanation. Steiner incorporated hermeneutics into translation theory, which was detailed in his bookAfter Babel: Aspects ofLanguage and Translationpublished in 1975.

The first is “trust.” According to Steiner (200l, p. 312), “We instinctively think that something is worth understanding and translating. All understanding and explanations made after understanding are translations, and all understanding begins with the step of trust.” Fu Lei believed that “Choosing the original works is like making friends. Some people are always out of place with me, so there is no need to force them; some people are like old friends at our first meeting, and we even regret that we could not meet earlier” (Chen, 2000, p. 386). Steiner pointed out that “usually, trust is instantaneous and does not need to be tested, but it has a complex foundation” (Steiner, 200l, p. 312).

The translator’s cultural level and language ability are the most powerful guarantee for the “trust” of the source text. As Lin Yutang (1998, p. 16) stated, “Translation is an art, and the achievements in this art depend on the individual’s talents, skills and whether there is sufficient training in this field. There is no shortcut to direct achievement.” Bonsall chose to translateThe Red Chamber Dreambecause of his strong Chinese proficiency as well as sincere love for and interest in Chinese literature. Bonsall spent 15 years in China from 1911 to 1926. After returning to England, he studied the Chinese language and culture tirelessly for years. In 1932, he completed his doctoral dissertationSpeeches of the States (The Kuo Yu): A Translation with Introduction and Notes. In 1934, he finished the 127-page monographConfucianism and Taoism(Wang et al., 2010, p. 198) and then finished the translation ofIntrigues of the Warring States, which laid a solid foundation for his translation ofThe Red Chamber Dream. When the translators chooseThe Red Chamber Dream, the cultural level and language ability are the internal motivation to endow the source text with trust.

From the external motivation, the important position ofThe Red Chamber Dreamin Chinese literature is also one of the reasons why Bonsall endowed “trust.” In the “translator’s preface,” Bonsall wrote that “But hitherto there has been no complete English version of this famous novel” (Bonsall, 2004, p. 6). His appraisal ofThe Red Chamber Dreamis a “famous novel.” According to the dictionary definition of “famous” as “renowned, noted, excellent (good in a high degree)” (Chambers, 1972, p. 472, 454), we can see that Bonsall gaveThe Red Chamber Dreama high appraisal. Secondly, Bonsall considered translatingThe Red Chamber Dreamat the suggestion of his son, Jeffrey. Jeffrey served as deputy director of the library of the University of Hong Kong from 1955 to 1969 and president of the Hong Kong University Press from 1970 to 1980. Having worked for so many years for the University of Hong Kong, he knew the important position ofThe Red Chamber Dreamin Chinese literature, so he strongly encouraged his father to translate it.

The second is “aggression.” Steiner (2001, p. 428) talked about “(at this step, the translator) is always partial” (Steiner, 2001, p. 428). It is “an inevitable aggression” (Steiner, 2001, p. 313) whether to the understanding of the source language version or to the author himself. André Lefevere (1992, p. 6) commented that “the translator is also constrained by his time, compromising on literary tradition and language features.” In the process of translation, the translator’s understanding depends on his own cultural awareness and different understanding of the source text. Each nation has its own unique customs, history, traditions, and ways of thinking, and these unique cultures are deeply engraved in everyone’s heart in different ways.

Idiom translations involving trust and aggression are discussed below.

老來富貴也真徼倖. 看破的. 遁入空門. 癡迷的. 枉送了性命. (Cao, 1934, I p. 36)

If old age comes with wealth and rank, that is of a truly good fortune. Those who see through this retire into the Gate of Vacancy. Those who are foolishly deceived, in vain, have given their lives away (Bonsall, 2004, I p. 52).

The dictionary definition of the idiomDun Ru Kong Men(遁入空門) is “avoiding the secular world and entering the gate of Buddhism, mostly referring to becoming monks and nuns” (Guo, et al. 2009, p. 202). Bonsall translatedKong(空) into “vacancy,” which does not convey the cultural connotation of “Kong” in Chinese. “Vacancy” is interpreted as “emptiness, leisure, idleness, inanity, empty space, a gap, a situation unknown” in the dictionary (Chambers, 1972, p. 1496). The translation only translated the literal meaning of the word “Kong” in Chinese but did not mention “enter the gate of Buddhism” or “becoming monks and nuns.” Here, the translator was influenced by the existing cultural awareness and has not given any explanation in the “Notes” section. Otherwise, according to the translator’s rigorous style, he would definitely give an explanation. There are many items in the notes section to explain the meanings of different religious terms in Chinese. For example, in Chapter 18, the translator interpretedLo-han(羅漢) as “The eighteen Lo-han were personal disciples of Buddha, sixteen Hindus and two Chinese. The five hundred Lo-han were distinguished followers or patrons of Buddha” (Bonsall, 2004 ⅵ), andZhen-ren(真人) as “‘Pure Man’-an honorable designation of a Taoist priest” (Bonsall, 2004 ⅵ). There are many examples in this respect.

Because translators have different experiences, preferences and language skills, their understanding is often different. Before translation, pre-understanding and “prejudice” already exist in the translator’s thinking, and the translator’s different understanding determines “to what extent the ‘otherness’ in the source text can be understood by readers, whether it is hostile or attractive” (Steiner, 2001, p. 314). Because of the translator’s pre-understanding, it is very easy for the target language readers to read it, and it may also lead to the translator’s misunderstanding of the source text, resulting in mistranslation.

虧你是進(jìn)士出身. 原來不懂古人有言. 百足之蟲. 死而不僵. (Cao, 1934, II p. 10)

Are you indeed a graduate of the third degree and still do not understand? The ancients had a saying: “An insect with a hundred feet does not fall when it dies” (Bonsall, 2004, Ⅱ p. 15).

可知這樣大族人家. 若從外頭殺來. 一時(shí)是殺不死的. 這可是古人說的. 百足之蟲. 死而不僵. (Cao,1934, Ⅲ p. 109)

It should be known that the people of a big clan like this, if foes rush in from outside, cannot be killed all at once. This is, of course, what the ancients said: “A hundred-footed maggot dies but does not go stiff” (Bonsall, 2004, Ⅲ p. 151).

Because of different cultural backgrounds, translators have different understandings ofBai Zu Zhi Cong(百足之蟲) in the proverb “Bai Zu Zhi Cong, Si Er Bu Jiang(百足之蟲,死而不僵).” According to the dictionary definition, “Bai Zu Zhi Cong” refers to “a multi-footed reptile, namely millipede, which has many joints in its trunk and can still crawl after being cut off” (Wen, 2011, p. 23). However, “insect” and “maggot” in the translation are not the meanings conveyed by Chinese. The English dictionary definition of “insect” is “a word loosely used for a small invertebrate creature, esp. one with a body as if cut in two or divided into sections” (Chambers, 1972, p. 677), which refers to a small invertebrate, an organism that can be divided into several parts. The meaning of “insect” is similar to that of “Bai Zu Zhi Cong.” “Maggot” is defined as “a legless grub, esp. of a fly” in the dictionary (Chambers, 1972, p. 788), which refers toJu(蛆) in Chinese, and the meaning of the translated version is far from that of the original. If understood literally, “Bai Zu Zhi Cong” may refer more to “millipede” in English. Due to the huge cultural differences and the influence of pre-understanding, translators may form different understandings, thus producing different translations.

The third is “incorporation.” After dealing with the aggression of the source text, the translator is faced with the text problem: how to deal with the relationship between the source language and the target language. At the “aggression” stage, the translator “grabs” the meaning and puts it in his mind, while at the “incorporation” stage, the “grabbed” meaning needs to be transformed into the target language.

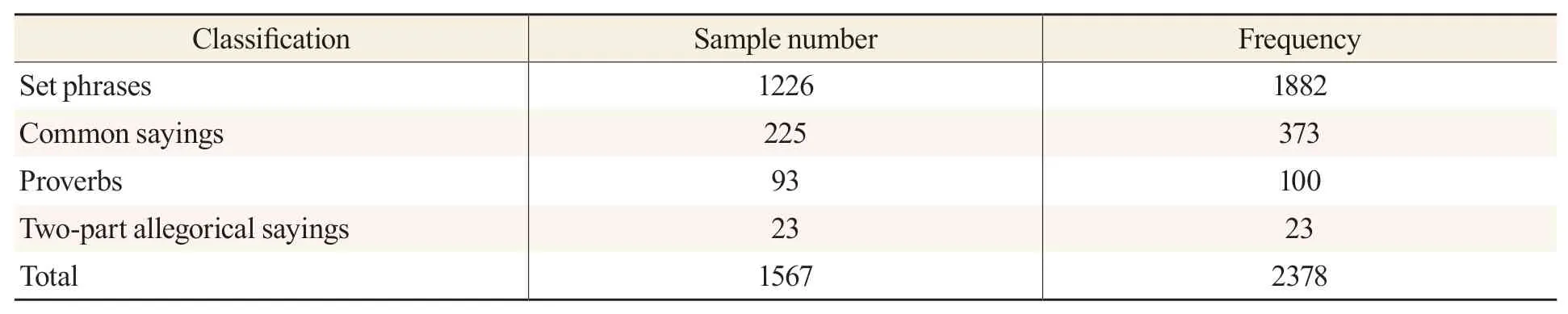

Idioms are everywhere inThe Red Chamber Dream. According to statistics, the conclusions are as follows:

Table 1 Statistics of Idiom Usage in the Guangyi Bookstore Version of The Red Chamber Dream (only statistics of 106 chapters) ① Idioms cover a wide range. Here, idioms are divided into set phrases, two-part allegorical sayings, common sayings, and proverbs, mainly referring to the following dictionaries: The Red Chamber Dream Chinese-English Idioms Dictionary by Gui Tingfang (2003); A Dictionary of Chinese Idioms by Guo Ling et al. (2007); The Red Chamber Dream Dictionary by Feng Qiyong et al. (1992); A Dictionary of Chinese Common Sayings by Wen Duanzheng (2011); Classified Dictionary of Common Two-part Allegorical Sayings by Shen Huiyun and Wen Duanzheng (2010) (3rd Edition).

Table 2 Statistics of Omitted Idioms in Bonsall’s English Version of The Red Chamber Dream

Table 3 Statistics of Idiom Translation in Bonsall’s English Version of The Red Chamber Dream

According to the above three tables, Bonsall mainly used literal translations, accounting for 66.0%, followed by a moderate combination with free translations, accounting for 29.0%, and a small proportion of combinations of literal translations and free translations as low as 4.9%. This shows that the translator aimed to keep the characteristics of the Chinese language as much as possible and tried to present the original appearance of the source text to the target readers through translation, as the translator said in the preface, “The translation is complete. Nothing has been omitted. And an attempt has been made to convey the meaning of each sentence in the source text” (Bonsall, 2004, p. 6). According to the above data, first, the translator has basically not abridged the idiom translations, and the proportion of omitted translations is only 0.13%. The translator aimed to convey all the meanings in the original work. Second, the translator was relatively faithful to the source text, with a literal translation rate of 66.0%.

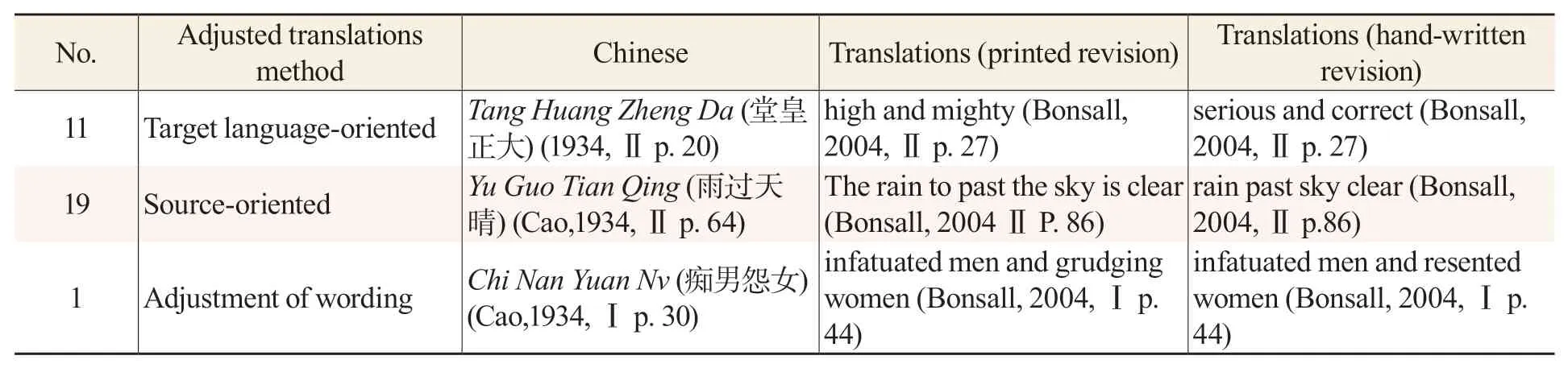

The typed version of Bonsall’s English translation ofThe Red Chamber Dreamwas obtained by heavy revisions and corrections made to the hand-written version. Through the typed version and hand-written version, we can see that some adjustments have been made to the idiom translations. According to statistics, Bonsall made 31 changes in idiom translation, as is shown below:

Table 4 Overview of Idiom Translation Adjustments in Bonsall’s English Translation

If literal translations were adjusted to free translations, we could guess that it was due to the “pressure” from the publishing house or readers’ preference, and interested researchers can write another article to discuss this. What is worth discussing is that Bonsall adjusted more in the direction of literal translations in the process of proofreading, which is intended to better present the style of the source text, and also confirms that the translator mentioned in the preface “and an attempt has been made to convey the meaning of each sentence in the original text” (Bonsall, 2004,p. 6). From the perspective of adjustments in the idiom translations, “external pressure” lost to Bonsall’s internal “initial intention” of translation, and he still focused on literal translation when checking and revising idiom translations, not forgetting the initial intention.

Steiner divided “incorporation” into “incorporation of meaning and incorporation of form” (Steiner, 2001, p. 315). Incorporation means in the process of transforming the source text into the target text, the translator uses different translation strategies to input information, sometimes at the expense of English syntactic rules to preserve meanings. Bonsall is no exception, and these translation strategies were brought into full play throughout the process of idiom translation.

何必作司馬牛之嘆. 你才說的也是. 多一事不如省一事. (Cao, 1934, II p. 104)

Why do you sigh like Ssǔ-ma Niu. That you said just now was right. To have one affair more is not as good as to have one affair less (Bonsall 2004, Ⅱ p. 137).

凡妹子所為都是他做主. 我想你素日曾勸我多一事不如少一事. 自己保養(yǎng)保養(yǎng)也就是好的. (Cao, 1934, III p. 103)

Whatever the younger sister does is under her direction. I recall that you constantly urged me that rather than having one more matter to attend to, it was better to have one fewer (Bonsall, 2004, Ⅲ p. 143).

For the first time, Bonsall translated the proverbDuo Yi Shi Bu Ru Shao Yi Shi(多一事不如少一事), into “To have one affair more is not as good as to have one affair less,” which is quite symmetrical with the source text. “To have one affair more” corresponds to “Duo Yi Shi,” “is not as good as” corresponds to “Bu Ru,” and “to have one affair less” corresponds to “Shao Yi Shi.” In addition, the translation itself is also very symmetrical. The subject “To have one affair more” has the same structure as the predicative “to have one affair less.” However, in the second translation, the former symmetrical form was reversed, and the meaning of the proverb was pursued instead. The balanced structure of two “to have …” was changed into a short sentence and a sentence with a “subject-copula- predicative” structure, breaking the balanced structure of the sentences, aiming at sacrificing the symmetrical form of sentences and expressing the meaning of the proverb. From this, we can also see that Bonsall’s efforts in expressing the meaning are evident.

In the process of translation, due to the differences between Chinese and English, it is sometimes difficult for translators to find a satisfactory expression, so it is difficult to achieve formal correspondence. At this time, the translator may try his best to take care of the meaning of the source language and the target language and apply some translation processing to better present the form of the source text in the target language.

我們何嘗敢大膽了. 都是趙姨娘鬧的. 平兒也悄悄的道. 罷了. 好奶奶們墻倒眾人推. (Cao, 1934, III p. 179)

When did we dare to be so bold? It has all been stirred up by Aunt Chao. P’ing-êrh said again in a low voice: “That will do, good ladies. When a wall is falling, everyone gives it a push” (Bonsall, 2004, Ⅱ p. 236).

他雖好性兒. 你們也該拿出個(gè)樣兒來. 別太過逾了. 墻倒眾人推. (Cao, III: 73)

Although she has a good disposition, you ought to treat her properly. Don’t go too far.

When a wall falls, everyone pushes (Bonsall, 2004, Ⅲ p. 100).

In the second translation of the proverbQiang Dao Zhong Ren Tui(墻倒眾人推), the translator made fine adjustments, changing the tense in the first translation from the present ongoing tense “is falling” to the simple present tense “falls,” and at the same time adjusting the phrase “gives it a push” to the verb “pushes,” so that the main clause has the same tense in the predicate, a more refined expression, and a catchy reading. Compared with the first translation, the meaning has not changed, but the second translation is more symmetrical in structure, achieving almost word-for-word correspondence with Chinese, with “a wall” corresponding to “Qiang,” “falls” corresponding to “Dao,” “everyone” corresponding to “Zhong Ren” and “push” corresponding to “Tui.” In the second translation, the translator pursued brevity, which coincides with the characteristics of proverbs, and achieves maximum balance and correspondence in terms of structure and form. Therefore, from this detail adjustment, we can see that the translator has worked hard on the translation form in the incorporation stage.

The fourth is “restitution.” The last step is restitution, which is essential for a credible translation. As Steiner (2001, p. 316) pointed out, “Interpretation must be compensated. If the translation is credible, it is necessary to consider the exchange and restoration of balance. The principle of reciprocity to restore balance is the most important thing of professional translation ethics.”

In the process of translation, the notes at the end of the translation can compensate for the loss of cultural elements caused by inevitable factors. It can restore the balance between the source language and the target language, enhance the understanding of the rich cultural connotations in idioms by readers of the target language, and help the translator to make the translation as complete as possible. InThe Red Chamber Dream, Bonsall wrote 43 pages, sparing no effort in explaining the culturally-loaded words mentioned in the translation.

我就是那多愁多病的身. 你就是那傾國傾城的貌. (Cao, 1934, I p. 147)

I am a person with many sorrows and many faults. You have the appearance of one who overthrows kingdoms and cities (Bonsall, 2004, Ⅰ p. 208).

Notes 8 (chapter xxiii): Suggested by the expression “The captivating smile of a woman who overthrows States and Cities.” These two sentences are taken from “The Record of the Western Chamber,” a later name for the Hui Chên Chi. of. chap. lxiv. n. 6 (Bonsall, 2004, 1B).

Here, the translator further explained the idiomQing Cheng Qing Guo(傾城傾國) in the notes, pointing out that this idiom inThe Red Chamber Dreamcomes fromXi Xiang Ji (Romance of the Western Chamber), which used to be known asHui Zhen Ji (Record of Meetings with the Perfected). Through the annotations, readers can understand the Chinese literature, culture and history conveyed behind “Qing Cheng Qing Guo.” Although Bonsall’s translation is long and verbose, it can help the target language readers discover the culture of the source language.

Conclusion

In Bonsall’s translation, idiom translations mainly adopted literal translations, supplemented by literal translations plus free translations, and free translations, which take the source language as the criterion. These are faithful to the source text and reflect the style of the source text to the maximum extent. However, idioms are important rhetorical devices in language, and they are the concentrated expressions of various rhetorical devices. People from different cultural backgrounds speak differently, and things have different functions in different environments. Therefore it is particularly important to adopt diversified translation methods. The translator can use the language resources of the target language (English), starting from phonetics, semantics, pragmatics, or discourse, properly taking into account the beautification of the translation and the rhetoric of Chinese and English idioms (such as antithesis, rhyme, alliteration, style, repetition of words, rhythm, tone, etc.) to express it (Zhang, 1980, p. 1). Compared with the single translation method in Bonsall’s translation, this variety of translation methods makes the characters more vivid, and the translated version expresses better in artistic effect. Compared with the single translation method in Bonsall’s translation, this variety of translation methods makes the characters more vivid and the translated version expresses better in artistic effect. Compared with Bonsall’s translation, the translation is target-oriented. Among the English versions ofThe Red Chamber Dream, the typical target-oriented versions should be Hawkes and Minford’s version and Wang Jizhen’s version.

Bonsall’s translation gives us some enlightenment in the idiom translation ofThe Red Chamber Dream. Translation of Chinese classics should adopt flexible and diverse translation methods according to the specific styles, specific rhetorical methods, and the needs of content transmission, and there is no need to stick to a unified translation mode throughout. This also provides some reference and reflection for future idiom translation.

Contemporary Social Sciences2021年6期

Contemporary Social Sciences2021年6期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- Wang Chuan’s Abstract Painting: A Contemporary Expression of Chinese Zen Ink Painting

- A Study of Feminine Space in Romance of the Three Kingdoms

- Wang Xizhi and Sichuan

- A Study of the European Union’s Path for Constructing Digital Governance Rules and the Logical Implications of the Path

- The Influence of Sichuan–Tibet Railway on the Accessibility and Economic Development of City Propers along the Line: Taking Chengdu and Ya’an as Examples

- Does Environmental Regulation Increase Employment? Based on the SCM and RCM Methods