Application and Regulation of Legal Science and Technology on the Pilot Program of the Reform of Separation between Complicated Cases and Simple Ones in Civil Procedure in the Basic People’s Courts

Yang Hui

Xihua University

Xu Yifei*

Sichuan University

Abstract: Blockchain, artificial intelligence, and other technologies have been increasingly integrated with the law, and the construction of smart justice and Internet courts in various places has a prominent effect on court informatization. The Supreme People’s Court is currently carrying out the pilot reform of separation between complicated and simple cases in civil procedure, and legal technology will inevitably become a major means to enable the reform. In the field of electronic litigation,legal technology itself has become a goal of the reform. Regarding the trials of pilot basic courts,legal technology has been more deeply applied in many links such as trial activities and trial management, playing an essential role in improving judicial efficiency, and becoming an important way to solve judicial dilemmas such as “l(fā)itigation explosion.” However, the history of modern society reminds us that we should be reasonably optimistic about the development of technology,especially in the field of justice.

Keywords: legal science and technology, the basic court, civil litigation, separation between complicated and simple cases in civil procedure

As classic statements of contemporary judicial dilemmas, concepts such as “l(fā)itigation explosion” and “more cases but fewer staff” have become important academic resources and a theoretical background for China’s current judicial reform.①“Litigation Explosion” was proposed based on scholars’ observations of British and American societies. Tang Weijian believes that the Americans’ concept of rights and over-reliance on the law resulted in a “l(fā)itigation explosion.” He also analyzed its positive and negative effects. See Tang Weijian: “The Legal Culture in American Civil Litigation,” in Science of Law (2000), Issue 3. Jiang Yinhua believes that the “l(fā)itigation explosion” reflected the vast contradiction between citizens’ demand for human rights protection and the supply of judicial resources, as well as the unreasonable allocation of judicial powers and resources. To alleviate the litigation pressure of judicial organs, the judicial reform should strictly safeguard human rights and reconstruct the judicial system at the functional level of violence and self-restraint of power, rights competition, reform, and realization of litigation rights so as to relieve the contradiction between human rights protection and judicial supply. In addition, Chu Qingdong, Ma Yaqing, Dong Chunhua, and other scholars also discussed this issue.Zhu Suli used the concept of “more cases but fewer staff” in the domestic academic circles earlier, arousing continuous attention and discussions. He holds that one important reason for “more cases but fewer staff” in China’s courts is that the cost of litigation remains too low. The court system should work with relevant decision-making departments to increase litigation costs by various measures. The cost should be borne by the fault disputer and reduced for other dispute resolution methods to lower the judicial needs of the entire society. See Zhu Suli: “Trial Management and Social Management: How Courts Respond to ‘More Cases but Fewer Staff’ Effectively,” published in China Legal Science (2010), Issue 6. In addition, You Chenjun, Jiang Feng, and Zhang Feng discussed the solution to “more cases but fewer staff” from historical experience and the perspectives of internal optimization, judge work measurement, arbitration and litigation separation, respectively.Since December 2019, authorized by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC)has successively introduced a series of important documents for the pilot program of the reform of separation between complicated and simple cases in civil procedure to clarify the content and steps of the pilot reform. According to these documents, the pilot program mainly focuses on optimizing the judicial confirmation procedure, improving the rules of small claims and summary procedures,expanding the application of the sole judge system, and improving the electronic litigation rules. The pilot work involved nearly 80 percent of cases in 20 cities in 15 prov0inces. Chengdu Intermediate People’s Court of Sichuan Province and all the basic courts under its jurisdiction were included in the pilot program. From the perspective of reform intentions, the SPC will, after the expiration of the trial period, synthesize local experiences and report to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on the results of the pilot reform. Relevant laws will be revised and improved; otherwise,previous legal provisions shall prevail. This pilot program involves major legal reforms in China’s civil litigation.

As the integration of law and technology has become an irreversible trend in the judicial field,the development status, reform measures, and the limitations of the legal technology in civil actions,especially in the two-year pilot reform of separation between complicated cases and simple ones in basic courts, are being discussed more often.②The integration of technology into the judicial field and its possible risks mentioned in this article were inspired by Zheng Hong. We hereby would like to give special thanks to Professor Zheng Hong.

Falling into Their Own Tracks: How to Separate Complicated Cases from Simple Ones in Civil Procedure

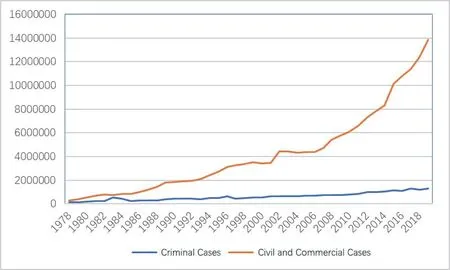

Richard A. Epstein observed that “in the United States, and more and more other places in the world, the confusion lies precisely in the excessive desire for the law,” and used “Too Many Lawyers,Too Much Law” as the title of the introduction of his book Simple Rules for a Complex World (Epstein,2004). In order to alleviate the surge in lawsuits and meet the society’s needs for litigation as a “public product,” the United States carried out institutional reforms to the civil/criminal litigation system after World War II, including consolidation of actions and plea bargaining, attempting to incorporate social conflicts into the legal framework. For more than 40 years since the reform and opening-up policy was introduced (in late 1978), compared to criminal cases, the number of first-instance civil and commercial cases handled by the people’s courts in China has shown a sharp increase. See Chart 1 for details:

Chart 1. First-instance Criminal Cases and Civil and Commercial Ones Accepted by the People’s Courts (1978-2019)Notes: The data were retrieved from China Statistical Yearbook 2020.

In 1978, the people’s courts handled more than 440,000 first-instance cases, and the number exceeded one million in 1982, five million in 1996, and ten million in 2015. By 2019, the number had increased to nearly 15.44 million. With the surge in cases, the judicial system has been under considerable pressure. Although we have been committed to exploring the diversity of dispute resolution methods, such as the Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), the political agenda of building the rule of law in China inevitably requires courts at all levels to serve as the last firewall to deal with social disputes. It can be seen from the trends described in Chart 1 that if there are no significant structural changes in the judicial system, the number of civil and commercial litigation cases will continue to rise.

To alleviate the judicial needs, the judicial reforms promoted by China have experienced ups and downs and have continued to date. From the 15th to the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, several phased goals were introduced, such as “promoting judicial reforms,”“promoting judicial system reforms,” “deepening the judicial system reforms,” “further deepening the judicial system reforms,” and “deepening the comprehensive supplementary reforms for the judicial system.” It can be seen from these phased goals that the focus of judicial reforms has gone through many changes and has trended toward increasing reforms. It might be necessary to deepen the reforms of the litigation system and promote separation between complicated cases and simple ones, between minor and major ones, and between slow and fast tracks. This expression was later documented in the current pilot reform program of the SPC.

To understand the original purpose of the reform of separation between complicated and simple civil procedures, one should first review the overall conception of the successive judicial system reforms jointly introduced by the Communist Party of China (CPC), the state, and the SPC, because the idealistic changes and the specific power relations will provide a particular structure or norms for the pilot reform. Zheng Ge believes that in an active country that attempts to transform society in accordance with political ideals, “the judiciary must be responsible for policy implementation, and this will inevitably bring about corresponding structural arrangements, including those concerning the political and legal systems (such systems will exclude the institutional arrangement that separate law from politics), the strict bureaucracy of judicial organizations, and the relationships among public security organs, procuratorate organs, and people’s courts to share the work and responsibility rather than to check and balance one another” (Damaska, 2005). This time, the pilot reform has carried the vision of modernizing China’s governance system and capacity in the judicial field. As Fu Yulin said, “Judging from the development and reform of civil justice in various countries, the separation between complicated cases and simple ones is aimed at putting the cases into their right tracks with rational norms to make it practically possible to uphold justice in ordinary procedures amid the fierce conflict between judicial resources and needs” (Fu, 2003). In a society that allows pluralistic values, how the judicial system shapes and regulates the means such as summary procedures and small claims to meet the surging judicial needs, thereby maintaining the judiciary’s authority and legitimacy, will become an issue worth further study.

“Smart” Justice: The Use of Technology in the Basic Courts

With the implementation of judicial reform measures such as the judicial accountability system,the classified management of court staff, the job security of judges, and the unified management of personnel and properties of local courts below the provincial level, due to the obvious advantages of scientific and technological means in improving the efficiency of traditional judicial routines, more and more scientific and technological achievements have been introduced into the judicial field. They are beginning to affect the current judicial practices. Chen Zengbao said, “As the world’s first Internet court, the Hangzhou Internet Court was officially opened on August 18, 2017. It has provided valuable experience and a vivid sample for establishing a new judicial form that adapts to the era of the rule of law and the Internet” (Chen, 2018). As a “milestone event in the judicial field,” the Hangzhou Internet Court handles the Internet-related cases through the Internet, which reflects the deep integration of traditional justice and modern technology.

Wang Fuhua explained the reason why modern information and communication technology is embedded in civil justice as “mainly due to its utilitarian value that can meet the needs of judicial pragmatism, and the fact that electronic litigation can also correct the formalization and nonpopularization resulted from traditional judicial professionalization.” Wang (2016) even suggested that “small claims and supervision procedures can be trialed in full electronic litigation.”①The impact and value of the formalization and non-popularization of the traditional judicial profession in the information age will be discussed by the authors in a separate article.Since the implementation of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China in 2013 and the issuance of the Five-Year Development Plan for the Informatization Construction of People’s Courts (2016-2020),the construction of electronic litigation and smart courts has become an important goal for China’s court system. Advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain have also begun to enter the field of civil trials. Some scholars even believe that “AI can partially replace judges on legal issues, while the blockchain-enabled system can completely replace judges on factual issues”(Shi, 2019). They asserted, “Blockchain can liberate judges from the hardship of fact-finding and is a productivity revolution in civil justice” (Shi, 2019).

To understand the situation of basic courts under the dual impact of huge judicial demand and internal reform, the People’s Court of Pidu District, Chengdu City (hereinafter referred to as the Pidu court), a unit for the practice and innovation of this pilot program, can be a good sample for investigation. Pidu District is located in the hinterland of the Chengdu Plain. It has a land area of 437.5 square kilometers and governs seven residential districts, three towns, and 155 villages (communities),with a permanent resident population of 1.08 million. There are eight main canals in the district,including the Puyang River, the Tuo River, and the Zouma River. Since ancient times, farming has been relatively developed, and the land is suitable for rice cultivation. In 2019, Pidu District ranked the 43rd on the list of “National Top 100 Districts by Comprehensive Strength” and the 52nd on the list of “National Top 100 Districts by New Urbanization Quality.” There are currently 38 posts of judges in the Pidu court. In 2019, a total of 14,663 cases were handled, of which 13,373 were settled, with a claim settlement rate of 91.2 percent. The average number of claims settled by a judge was 352, while the figure for a front-line judge was 461. The Pidu court has been integrating blockchain, big data, AI,and other scientific and technological means into the judicial process. In June 2019, the SPC issued a document regarding the application of blockchain technology to judicial evidence storage. The Pidu court was selected as the only typical application case for reference in western China. In August 2019,the SPC established a unified national judicial blockchain platform. The Pidu court was one of the first two basic courts in China to join the platform. In December 2019, the SPC issued the first white paper on Internet judiciary. The Pidu court’s “promoting the blockchain evidence storage for cultural and creative works and enhancing the protection of intellectual properties and innovations” was included in the evaluation.

In addition to blockchain application, the Pidu court also established an Internet court to promote electronic litigation and smart court trials. The Internet court was officially launched in Jingrong Town on June 22, 2018. It has become the first Internet court in western China to handle concentrated trials in ten types of Internet-related first-instance civil and commercial cases within the jurisdiction of Pidu District, including but not limited to contract disputes arising from online shopping, Internet service, financial loan, and Internet insurance (Chen, 2019). According to its conception, litigants have access to litigation services such as prosecution, case filing, evidence adducing, cross-examination,opening a court session, and applying for execution. They can also complete identity verification,online case filing, attendance at a trial, and case progress inquiry via their mobile phones, thus realizing the whole online process from adducing evidence to cross-examination, from court opening to mediation, and from verdict to execution.

The Pidu court has also attempted to perform smart court trials. At present, it can transfer offline prosecutions to online court sessions, and allow litigants to attend court trials remotely without registration. The court uses voice recognition technology to electronize the trial record. The use of blockchain evidence storage is also encouraged in the court’s litigation activities. It can be seen from the above that the Pidu court has accumulated experience and system innovation in constructing Internet courts, smart court trials, and judicial blockchain. The pioneering trials of the court in judicial concepts, systems, and practices have become the main reason for the research group to choose the Pidu court as the practice innovation unit for the pilot reform of separation between complicated and simple civil procedures.

Technology Integration: Reconstructing the Civil Procedures

Based on the five basic tasks of the reform, the Pidu court has explored, innovated, and tried to institutionalize certain practices that have proven to be effective. For example, in advancing the reform of small claims procedures, the court has established a guiding mechanism for automatic identification and interpretation by a dedicated person, expanded the scope of application of small claims, and improved the approval mechanism for converting small claims procedures. It has also attempted to establish a whole-process management and control mechanism to strictly control the time limits of case acceptance, delivery, the opening of court sessions, closing, and archiving. The system automatically reminds and urges parties concerned when the deadline of each process is approaching.In terms of optimizing judicial confirmation procedures, the Pidu court, in collaboration with local authorities such as Pidu District Justice Bureau and Pidu District Intellectual Property Administration,established an in-court mediation committee and a service center for in-court intellectual property mediation, promulgated detailed implementation measures on how to carry out judicial confirmation of non-litigation mediation agreements in the reform of separation between complicated and simple civil procedures, introduced specially-invited mediators from the field of law and administration, and set up an offline litigation-mediation connection platform to promote the work related to speciallyinvited mediation. Meanwhile, the Pidu court also connected the “Hehe Zhijie” (和合智解)— an e-mediation platform, to the mediation platform to the comprehensive management platform of Pidu District to build a one-stop online platform for dispute resolution.

Comparatively speaking, the pilot reform to improve the rules of electronic litigation has the highest degree of relevance to science and technology. The experience of the Pidu court is mainly reflected in three aspects. The first is to realize real-time data interaction preliminarily. By breaking the data barriers between internal and external networks, litigation materials recorded on the external network can be synchronized to the internal network system. Case materials stored in the internal network can be invocated synchronously during the online court session. The audio and video data of the online court session can also be stored synchronously on the internal network. By cooperating with two major Chinese communication operators, China Mobile and China Unicom,massive user data are used to establish a smart delivery system and repair the information of missing persons so as to create favorable conditions for delivery; by connecting with the data of the notary office and establishing an online submission and verification mechanism for notarized evidence,multiple notarized certificates have been submitted and verified online. The second is to improve the blockchain platform for electronic evidence storage. By creating the Life Path Enforcement System (生道執(zhí)行系統(tǒng)), the Pidu court resolved trust problems using technology. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, it helped some struggling enterprises to tide over the crisis. The reform experience was reprinted by the Intelligent Court in Progress (智慧法院進行時), an official Wechat account linked to SPC Information Center, reporting on informatization of courts. The third is to promote electronic litigation further actively. Platforms such as the Forum on the Rule of Law Regulating the Development of Sichuan Service Industry respond to issues that companies are concerned about, such as the respective advantages of online litigation and traditional litigation,electronic data proof, and legal protection of signing electronic contracts online.

To standardize the trial process, the Pidu court focused on the three core dimensions of the electronic litigation process, court trial, and evidence. It (1) formulated five regulatory documents to establish systematic rules for guiding electronic litigation; (2) standardized the electronic litigation process and made it more orderly; (3) set up pre-trial technical testing to ensure that the equipment and network meet the requirements for online court sessions; (4) established an online pre-trial evidence exchange system to allow litigants and lawyers to use the electronic litigation platform for evidence presentation and cross-examination synchronously or asynchronously; (5) hired technicians especially for court trials to assist judges and litigants in resolving technical problems; and (6) standardized the behaviors of online court trials to make it more rigorous. The judges shall preside over the trial in court. If the trial cannot be held in the courtroom under particular circumstances, the place for a court hearing shall feature the judge’s bench, the national emblem, the court gavel, and the names of the seated personnel. Litigants and other participants shall choose a quiet and relatively enclosed place with light and network signal suitable for their participation in the trial. In view of the characteristics of online trials, it is specifically stipulated that the litigants cannot deliberately leave the trial screen and cannot allow irrelevant personnel to provide suggestions at the scene. To tackle violations of court discipline, in addition to traditional penalties, it is also stipulated that audio and video functions shall be manually turned off.

The application of blockchain technology in evidence is bound to pose a challenge to the structure of traditional evidence law. The SPC issued a document regulating issues concerning the trial of cases by Internet courts in September 2018, which recognized the legitimacy of blockchain evidence through judicial interpretation. Zhang Yujie believes that “the ‘rule of law’ significance of blockchain evidence is by no means limited to the simple positioning of emerging electronic evidence, but also lies in a comprehensive innovation of evidence qualification, original theory, and proof paradigm,which cannot be directly addressed by the current evidence law system” (Zhang, 2019). More importantly, as blockchain evidence has gained legitimacy, we must establish rules for the review and determination of online/electronic evidence so that it can exert a significant impact on civil proceedings.

In the judicial practice of the Pidu court, blockchain technology has been continuously tried and used in individual cases. The court used the characteristics of blockchain such as distributed storage,tamper resistance, and traceability to establish a blockchain/electronic evidence platform, striving to achieve the full-process recording, full-link credibility, and full-node witness of electronic evidence.For the structured information generated and stored on the electronic evidence collection and storage platform and e-commerce platform, the court can directly obtain and import information into the electronic litigation platform. Regarding the authenticity of electronic evidence, relevant object identification involves the authenticity identification of electronic evidence generation, collection,storage, and transmission. In terms of content review, a comprehensive review of the electronic data generation platform, storage medium, storage methods, extraction subject, transmission process, and verification method should be carried out. In terms of identification methods, litigants are encouraged and guided to fix, retain, collect, and extract evidence through the blockchain/electronic evidence platform, to make up for the deficiencies of identifying electronic evidence only through notarization procedures and improve the effectiveness of electronic evidence.

Meanwhile, the Pidu court has established a blockchain-enabled smart contract system to implement the Internet governance of the litigation source. Using the characteristics of blockchainenabled smart contract technology that is based on predetermined conditions or time trigger, tamper resistance, and automatic enforcement, the Pidu court deployed formatted contracts such as the Internet financial loan contract to the system to record the entire process of signing and fulfilling financial loan behaviors, and to realize the automatic performance of the contract, automatic case filling for performance failure, smart mediation, smart trial, and automatic execution. To improve the summary procedure rules, the Pidu court has established an elemental smart judicial system in response to five types of frequent disputes: road traffic, labor use, house sales, private lending, and marriage and family. The system uses technology, such as voice recognition, OCR text recognition,and smart court trial, to extract trial elements accurately, position the focus of disputes intelligently,transfer similar cases and related laws and regulations accurately, remind judges of important processes throughout the trial, and improve the judicial efficiency. In terms of expanding the application scope of the sole judge system, a special session for sole judges has been established to regularly discuss difficult issues encountered in trials; the writing of adjudicative documents has been standardized; the judgment criteria have been unified.

In addition to the five tasks, the Pidu court is also advancing the reform of separation between the complicated and simple enforcement work. First, the Pidu court reorganized the enforcement team to handle transactional work intensively. It sorted out and summarized the enforcement judges’transactional work, which would be segmented and intensively enforced by the newly formed teams responsible for enforcement and implementation, asset disposal, and comprehensive logistics. Second,the Pidu court reconstructed the case-handling process to realize the dynamic separation of cases.After a case is filed, the comprehensive logistics team will implement separation based on the result of property inquiries. For simple behavioral cases such as cash available for enforcement and assistance in the transfer of accounts, the execution team will quickly conclude the case, and the others will be diverted to the case enforcement team. A second property investigation will be initiated for cases that are not enforced after traditional investigations and enforcement measures. Third, the Pidu court also reshaped the regulatory system to visualize supervision and management. Relying on the enforcement command center, a center for quality and efficiency management has been established to form a regulatory system where the assistance team manages the general affairs, the enforcement judges manage the case, and the command center manages the whole process. The judges manage the case file, and the assigned affairs are circulated among the teams. Processes are connected smoothly, and the responsibilities are clearly defined.

Efficiency Leap: The Positive Effects of Technology on Traditional Justice

According to some scholars, “What lawyers, scholars, and the courts are discovering is that some kinds of evidence, most notably some of the forensic sciences, which had been all but unquestioned under older admissibility tests, appeared to have startling weaknesses when viewed through the lens of the new test” (Parker & Sachs, 2015). DNA typing technology has become an important method for those who have suffered injustices due to wrong judgments in the United States. Just like the rise and success of DNA evidence, the latest technologies such as blockchain and big data continue to be applied in the field of justice in China today. Although we do not know where the court trial will eventually be taken to, these advanced technologies have shown their enormous vitality in judicial practice.

Just as Hou Meng said when observing the effects of Internet technology on the Hangzhou Internet Court, “Internet technology has a comprehensive effect on justice. It not only reduces litigation and trial costs but also changes trial management and methods.” Internet technology will profoundly change the operation mode of courts and even challenge traditional trial principles. He even said optimistically, “Internet technology has enabled the court to measure litigants’ feelings of fairness and justice more accurately” (Hou, 2018). Indeed, the extensive application of scientific and technological means in the judicial field has brought many positive effects to this traditional “industry.”Huang Qiaojuan and other scholars have also reviewed (Huang & Luo, 2018) the status quo and trend of the integration of AI and law from aspects such as legislation (AI system assisted legislation and legislative supervision of AI systems, especially autonomous driving vehicles), acquisition of and abidance by relevant laws (legal information retrieval, legal document generation, and review), and justice (evidence collection, legal reasoning, and online dispute resolution). It can also be seen that the effect of technology on the legal field has touched all aspects.

For basic courts that are mainly under the pressure of a sharp increase in the number of cases,what changes these new technological means have brought to improve the quality and effectiveness of civil cases can be investigated from a series of data. Regarding the electronization of small claims, in response to the high cost of rights protection and lengthy litigation procedures in Internet intellectual property cases, the Pidu court used Internet technology to establish an online litigation platform fully accessible from PC and mobile terminals. As a result, litigants can participate in the whole litigation process from prosecution, case filing, payment, evidence adducing and cross-examination to court hearings without leaving their homes. The platform makes litigation as convenient as “online shopping” and ensures litigants of Internet intellectual property cases “zero travel time” and “zero travel expense” so as to better satisfy their judicial needs for “l(fā)ow cost” and “fast trial.” According to the data revealed by the Pidu court, the number of cases in 2020 increased by 37.83 percent, of which small class actions accounted for 35 percent of the increase. The court made full use of the two-year pilot experience of the Internet court to create a new electronization model for small claims, which vigorously improved the quality and effectiveness of such cases. In 2020, the Pidu court concluded 1,702 such cases, and the average number of trial days was reduced by five days to 20 days, saving 18 travel hours and RMB1,500 travel fee per litigant.

In terms of rapid adjudication of similar cases, the Pidu court effectively integrated the mechanism of intellectual property cases with information technology to establish a platform for such cases. In 2020, the Pidu court upgraded the platform for adjudication of similar cases and explored ways to digitalize class actions for small labor claims, sales of commodity houses, class actions for lease contracts, class actions for property management, and disputes over traffic accidents through elemental trials, which proposed the dispute resolution procedures for these types of cases. Since its operation started in 2020, a total of 1,507 cases of various types of similar class actions have been quickly concluded; the average case filing time for litigants has been reduced by 80 percent; the average delivery period has been reduced to nine days from 38 days; the number of court trials has reduced more than 900; the average time for court trials has declined to 20 minutes; the average trial period has reduced to 22 days.

In early 2020, the Internet court of the Pidu court successfully resolved more than 1,300 disputes,held 517 online court hearings (30.5 percent), filed 4,343 cases online (40.65 percent), and delivered 15,976 cases electronically. The court insisted on completing the whole process of online trial, used science and technology to facilitate the trial, and effectively minimized the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on litigants. In terms of the electronic evidence review, the blockchain/electronic evidence platform effectively resolved the difficulties in electronic evidence identification (caused by a large amount of electronic data), strong real-time performance, and identification of originals, thus helping judges to review and making judgments and increasing the acceptance rate of electronic evidence. Up to now, more than 20,000 pieces of evidence have been stored on the platform, and the litigants of 118 copyright infringement cases have obtained and stored their evidence through the platform.

Technology Myth: Rules of Code and the Gradual Disappearance of “Human”

The coupling relationship and evolutionary process between law and technology are gradually increasing. Through the efforts of legal service enterprises such as pkulaw.cn, informatization has been basically realized. The automation stage of decision-making procedures, which mainly relies on computer applications for law retrieval and comparative analysis, can currently be used to develop software for tax, accounting and credit evaluation. With the development of technology, there may not seem to be a major technical obstacle to the regulation of legal rules and the application of code.Taking the integration of AI and justice as an example, some scholars are full of confidence that AI can form a value judgment and ultimately try cases instead of judges. Peng Zhongli (2021) believes that the fundamental reason why judicial judgment is not a “vending machine” is that “judges can judge value in judicial cases, while AI, based on a mechanism that simulates the brain’s operation,deep learning theory and computer reading of human psychological state to deal with value problems,cannot do so.” “From a technical level, the existing technology has provided the possibility for the judicial judgment to analyze the value issues.” However, AI can mimic human value preferences and make judicial judgments based on specific facts and coded laws once the value dataset is formed.

A review of the operation practice of the Internet court of the Pidu court shows that the concept of trial order, the behaviors that disturb the order, the ways to maintain the order, the ritualization of the court trial, and the theatrical effects have all undergone major changes. The new situations in the Internet trial mainly include (1) litigants’ frequent absence from the court for reasons such as network instability and power failure; (2) an “unclean” trial environment on the litigant side; (3) the litigants’ actions of using Internet viruses to infringe on the Internet trial system to interrupt the trial.There is a lack of a corresponding legal system to regulate the above-mentioned new behaviors of disrupting the trial order. Meanwhile, due to the absence of judicial police in Internet court trials and the limited implementation of police powers, the means to maintain the court trial system are also lacking. The original intention of judicial etiquette was to allow every citizen to participate in court trials to feel the sacredness and majesty of China’s judicial power. The national emblem, judges,robes, and the court gavel are all theatrical methods to symbolize “l(fā)egal justice” and “procedural justice.” The virtualization of the Internet trial has reduced their effects, and the judiciary deterrence is greatly diminished as a result. With the gradual embedding of modern science and technology into the traditional judicial field, the court trial process that was once sacred and mysterious has been continuously disenchanted.

With the transformation of judicial scenarios, maintaining court order has become a difficult problem in Internet court trials. The main reasons are as follows: First, the virtualization of court trials has significantly weakened judges’ control over the courts. In offline court trials, litigation participants are not allowed to perform audio recording, video recording, and photo-taking without permission.①Article 176 of the Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on the Application of the “Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China.”However, judges do not have the ability to monitor the entire trial activity in an online trial. Thus, even if the litigants are found to have violated the law, it is difficult to stop or punish them in time. Second, the virtualization of court trials has significantly weakened the function of judicial ceremonies. In online trials, the judges and the two parties are presented with the same images on the computer or other electronic terminals. There is no obvious difference in the status of the three parties. This puts the judge in the center of the judgment in an equal position with litigants,which weakens the judiciary’s authority and sacredness. Third, the formalization of court trials has reduced the litigants’ sense of identification with judicial decisions. Internet courts tend to pursue the convenience and efficiency of litigation services, and go through formalities in the stages of identity confirmation of litigants, the reading of court disciplines, court debates, and court investigations.Pursuing efficiency at the expense of sacrificing a quality trial has become a common problem in many Internet courts.

However, with the transition of court trials from reality to virtual, Internet courts have brought about problems such as reducing judges’ control over the courts and weakening judicial etiquette functions. With the development of AI and other technologies, their application scenarios will inevitably cover fields such as traditional agriculture, industrial manufacturing, medical care,finance, and even law. Chinese scholars have similar insights on this. Li Zhen believes that AI has the potential to intervene in the justice system in four aspects in an incremental approach. The first is to gradually replace human power to engage in relatively simple mechanical and highly repetitive tasks such as legal inquiries, case retrieval and classification, and court trial recording. The second is to assist in completing auxiliary tasks such as judicial consultation, contract review, evidence acquisition, and judicial document generation. The third is to conduct statistical analyses and make predictions based on a large number of judicial documents to provide reference information for judges. The fourth is to directly or partially participate in decision-making, such as recidivism risk assessment, the judgment of the suspect’s escape possibility, and the reasonable sentencing calculation (Li, 2020). According to Li’s prediction, the full intervention of AI in the judicial field is unstoppable.

The State Council, in 2017, issued a plan concerning the development of AI in the next generation,which stated, “AI is a revolutionary and widely influential technology that may bring about issues like changing employment structure, impacting law and social ethics, infringing personal privacy,and challenging international relations. It will deeply influence government management, economic security, social stability, and global governance.”①Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan, No. 35 [2017] of the State Council, released on July 8, 2017.If we allow the development and application of AI technology without limits, it is conceivable that AI judges that previously only appeared in sci-fi works will become a reality in the not-too-distant future. The development of modern society has repeatedly reminded us that when we ignore the idea that “technology is only an auxiliary means to make our lives better, rather than life itself,” the technological development is likely to backfire.

Conclusion

We are moving towards a world dominated by science. German sociologist Ulrich Beck also has an analogy in his masterpiece Risikogesellschaft: Auf dem Weg in Eine andere Moderne, which reminds us that our modern society is “on the volcano of civilization.” He argued that science is an important factor that makes everything work, but it does not care about the consequences (Beck,2018). The combination of law and technology has indeed greatly alleviated the dilemma of “more cases but fewer staff” in basic courts. It is even now generally regarded as the primary way to solve the “l(fā)itigation explosion.” However, if we rely too much on technical means and ultimately achieve automated or code-based legal governance, in addition to our desirable goals such as enhancing efficiency and transparency, will it also produce unforeseen problems and even endanger people’s freedom and autonomy? Such doubts are not unfounded.

The rapid development of the current judicial information technology research and application in China has brought the risk of excessive “technicalization,” “openness,” and “popularization,” which poses a serious threat to judicial rules, professionalism, and humanity. Sun Xiaoxia believes that we should set a limit for judicial information technology, especially at present, and that China should determine three principles from the judicial and humanistic perspective: (1) avoid threats to litigants’ fair trial right;(2) avoid encroaching on the sacredness of the court; and (3) avoid having blind faith in and rely too much on AI judgments, while ignoring complex propositions unique to humans (Sun, 2021). Judicial informatization and intelligentization have their own value, but the out-of-control technology expansion requires constant vigilance. When we enjoy the cheapness and convenience it brings, the crisis that could endanger the existing order and the dignity of humans is often deeply buried.

When discussing the alienation caused by the social division of labor by Marx and Durkheim,Anthony Giddens mentioned in particular, “It is only through moral acceptance in his particular role in the division of labor that the individual is able to’achieve a high degree of autonomy as a self-conscious being, and can escape both the tyranny of the rigid moral conformity demanded in undifferentiated societies on the one hand, and the tyranny of unrealizable desires on the other ”(Giddens, 1992). From the long judicial history of humankind, it is precisely people’s sense of morality and complexity, as well as the contradictions and conflicts between religious concepts or moral emotions, and legal rules that promote the legal professional community in a broad sense, such as judges and lawyers to pursue justice through individual cases. As for whether advanced technological methods such as AI can make correct fact determination and value judgments in complex propositions to realize the justice of individual cases and replace human judges in the ultimate sense,we, the authors, hold a negative opinion.

The growth in complexity and acceleration of modern society have resulted in “the explosive increase of laws and litigation, information overload, functional differentiation, and a sharp increase in risks. It is now necessary to form a new understanding of people about themselves and the world in which they live.” Lu Nan referred to the statement of German philosopher Karl Jaspers about the“magic” of technology, which suggests that “in the post-human condition where the law is conceived as code, people must have confidence in imagining and facing a highly uncertain future because hope is originated from uncertainty” (Lu, 2019). We believe that our hope lies in believing that human beings have always used tools to deal with uncertainties rather than developing technologies that replace us in making all important decisions.

Contemporary Social Sciences2021年5期

Contemporary Social Sciences2021年5期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- 《當代社會科學(英文)》稿件格式參考Manuscript Format

- Research and Analysis on the Origin of the Term “Xinche” in Traditional Chinese Medicine and Its Translation

- A Study of the Pit-Aided Construction of Egyptian Pyramids

- The Significance of Inter-Cultural Communication of “Panda Fever”— A Case Study of “Meng Meng” and “Jiao Qing” in Berlin

- Review of Environmental Governance Research since the 18th CPC National Congress— Based on Bibliometric Analysis

- A Study on Establishing a Crossborder E-commerce Logistics System for Agricultural Products in Sichuan Province in the Context of the Belt and Road Initiative