Issues concerning the science communication ethics of science and technology museums

Xiang Li and Xuan Liu

National Academy of Innovation Strategy,China

Huiping Chu

University College London,UK

Abstract This paper reviews the acceleration of what is known as the ‘museumization’ process globally in the context of the New Museum Movement,and the particular mission of science and technology museums in representing scientific culture.It analyses the significance of science and technology museums in presenting critical concepts of contemporary science and technology,such as the controversies and uncertainties of science,as well as the diverse subjects that need to be involved in the process of representation,thereby underscoring the complexity of the ethical issues of science communication faced by science and technology museums.

Keywords Ethics,museumization,science-centerization,science communication

On 24 September 2020,at a conference held in Changzhou,Jiangsu Province,five organizations(the Chinese Association of Natural Science Museums,the China Science Writers Association,the Chinese Society for Science and Technology Journalism,the National Academy of Innovation Strategy and Beijing Guokr Interactive Technology Media Co.Ltd) jointly issued the ‘Initiative on Science Communication Ethics’.The initiative underscored that good practices of science communication need to be guided by correct ethical norms,and that science communication workers should take the initiative to enhance ethical awareness and consciously assume social responsibility.As important platforms for science communication and essential venues for presenting scientific culture,science and technology museums1are faced with ethical issues confronting the entire science communication industry.In addition,given the historical heritage,theoretical system,construction pathways and development trends of the museum industry,science and technology museums also have to deal with a particular set of issues concerning science communication ethics,which should be considered and addressed based on the industry’s own characteristics.

1.The process of world museumization is gaining speed

In contemporary studies of museum history,the concept of ‘museum’ in the modern sense is usually traced back to the Age of Discovery and the material and cultural exchanges it inspired.Museums are social institutions that promote the reconstruction of materials and cultures,so their construction and development generally go through the process of gathering cultural vehicles,disseminating information and reconstructing culture.In other words,the process transforms material and information derived from different fields and spaces into a museum’s contents.Science and technology museums,which are part of this category of social institutions,also follow that pattern.Moreover,with the acceleration of global material and information exchange,the pace of worldwide ‘museumization’2is also quickening.

1.1.From collection to display:The traditional process of museumization

The English word ‘museum’ comes ultimately from the Greek wordmuse,referring to any of the nine goddesses of art and science in Greek mythology.Additionally,the English word ‘muse’ is derived from the French verbmuser,which means ‘to think deeply’.As the origin of the word indicates,the fundamental mission of a museum -a public space in nature -is to promote an understanding of the world as a whole (Schiele and Koster,2007).Although museums vary in form,content and cultural context,they generally undergo a common process of gathering,reorganizing and exporting materials and information,which is typically reflected in the collection,preservation,research and display of materials in traditional museums (Burcaw,2011).Early science and technology museums,such as the relatively mature Science Museum in London and the Deutsches Museum in Munich,also take the collection and research of scientific instruments and historical materials of science and technology as their main function.

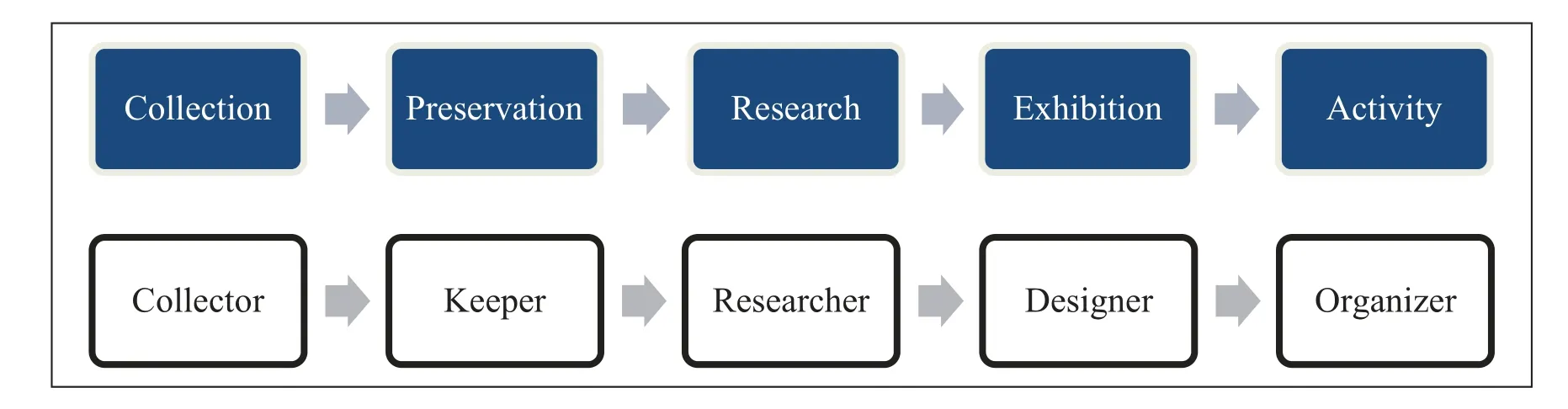

The ‘a(chǎn)ntique gallery’ of the Renaissance period can be seen as the predecessor of museums -or,more specifically,the pre-historic period,in the case of science and technology museums,as a sound and mature concept of ‘science’ had not yet been developed during that period.From the emergence of natural history museums at the end of the 16th century to the maturity of science and industry museums by the 20th century,as well as the mushrooming of science centres that focus increasingly on public education (Wang,1990;Zhu,2014),science and technology museums have not only completed the chain of museumization as part of the development of the whole museum industry but have also moved to the forefront of interactive displays represented by science centres.Figure 1 summarizes the general sequence of the museumization of materials and information.Although science and technology museums,depending on their specific content and category,may have varied focus in the five steps outlined,or may even skip some of the steps and move directly into a successive stage,the pattern remains applicable for the whole industry.In the case of science centres,for example,while there is a strong focus on the educational activities at the end of the chain,the creation of science centres was itself based on the evolution of natural history museums and science and industry museums,both of which have a particular focus on collection and research.

Figure 1.The general chain of museumization.

Figure 2.Actors in the museumization process.

1.2.The New Museum Movement:Acceleration of the museumization process

The New Museum Movement,which began in the 1960s and 1970s,is representative of the acceleration of museumization worldwide.As Hugues de Varine,former secretary general of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) (1964-1974),observed,traditional historical sites,monuments and museums were increasingly protected and collections of artefacts expanded during that period (De Varine,2005).The rapid growth of museums and the number of artefacts in their collections and exhibits brought about higher demand on the supply side.In short,both the high public demand for museums and the urgent need for cultural content to manifest its unique cultural value through self-representation have necessitated the acceleration of the museumization process.Consequently,the increased speed of museumization prompted by the New Museum Movement has been perceived as a welcome outcome by cultural producers,communicators and consumers alike.

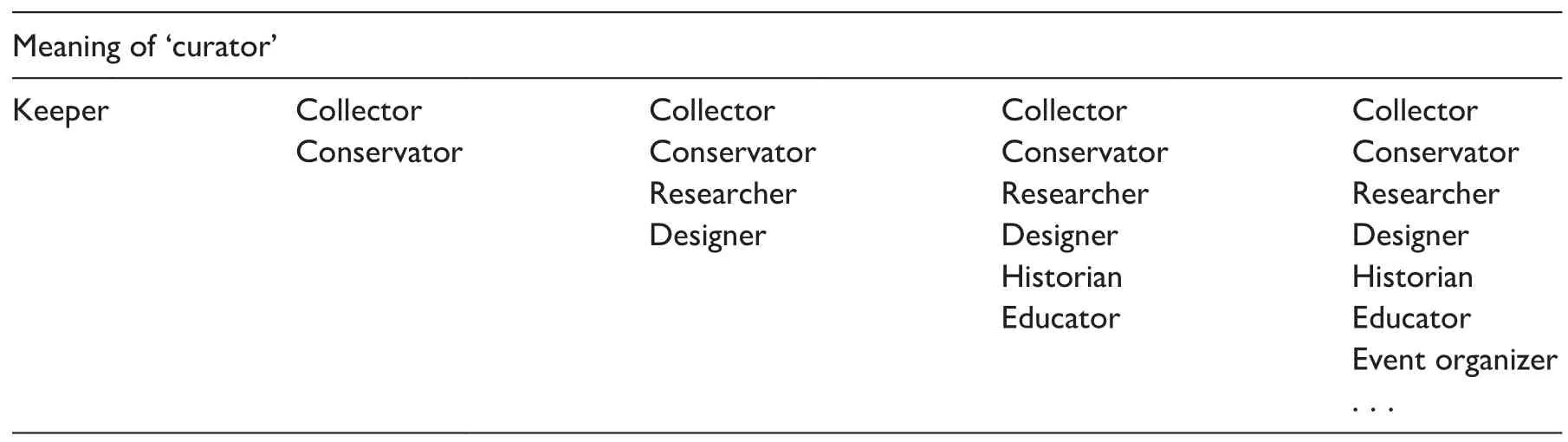

As the traditional museumization process that had focused on the supply side,such as collection and storage,shifted towards a new trend characterized by exhibitions and events,it was inevitable that essential players in the core steps of the museumization process,such as collectors,researchers and designers,would begin to share the workload of museum content production and judge the value of the contents based on the themes of the museums(Figure 2).The traditional process of museumization is based on time-honoured collections that have been strictly tested and widely appraised.It is a slow process of accumulating and being tested by elite knowledge.In comparison,the museumization driven by the New Museum Movement brings together experts from different fields.Such a sophisticated division of responsibilities has added a classical colour to the traditional encyclopaedic model of management,making it difficult to continue.The role of museums is increasingly shifting from the presentation of material objects to the interpretation of their meaning,and the generation of such meaning is inevitably accompanied by the involvement of more diverse actors (Xu,2015).Within this transformation process,museums cannot avoid the ethical dilemma that,even if the experts in charge of various aspects of the process follow the established rules,the social meanings that are pieced together might still not escape ethical failures.

1.3.Demonstrating scientific research:The development trend of science and technology museums

If the accelerated museumization process inspired by the New Museum Movement was directed at the museum industry as a whole,the impact of the Public Understanding of Science Movement,which began in the 1980s,has been even more pronounced (Li and Liu,2003).The public has increasingly demanded the right to know about science and is no longer satisfied with apprehending only the final results of scientific research.More importantly,in relation to topics that are closely related to people’s daily lives,such as genetically modified food and nuclear energy,the public demand for participation in scientific decision-making,which must be based on a proper understanding of the research process,has also grown stronger.In 1996,the Science Museum in London organized its first workshop,‘Here and Now’,promoting a lively discussion on ways for museums and science centres to better present contemporary science and technology.Three years later,the Nobel Museum and the Center for History of Science at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences organized another conference on the same topic (Chittenden et al.,2004;Farmelo and Carding,1997).

As ‘unfinished’ science,scientific research processes are naturally more difficult to communicate than established scientific knowledge recorded in books -although they are more effective in highlighting the cultural value of science.Against this backdrop,a new ethical dilemma has arisen for science and technology museums:instead of presenting mature knowledge from the past,they need to possess and present a greater grasp of the scientific research process.Through a case study of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California,Berkeley,3Susan Leigh Star has discussed the attributes of museums as boundary objects and their interactions with other public institutions (Star and Griesemer,1989).Once the exhibits of science and technology museums have been expanded from definite results to the uncertain process of scientific research,the institutions themselves shall no longer be seen as boundary objects with relative independence,but rather as junctional domains where different cultures interact.As a standard of ethical norms,the difference in the value compasses of various cultures is a challenge that all museums have to deal with.

Changes in the social environment will inevitably affect the public’s attitude towards ethics and the ethical concepts governing behaviour.Therefore,given the growing acceptance of cultural diversity,the community of the museum industry is bound to face the challenge of multiple ethical concepts in the process of collection and exhibition (Edson,1997).For example,in the case of science and technology museums,the acceptance of human body exhibitions varies from region to region,due to differing cultural backgrounds;hence the need for museum exhibitions to factor in the diversity of their audiences -especially for museums that have target audiences with highly internationalized ethnic and cultural backgrounds (Zhang,2005).Even in a unified cultural context,it is necessary to fully consider the abilities of people of different ages,genders and educational levels to accept an exhibition’s contents (Canadian Museums Association,2006;ICOM,2017).

2.Controversial science:Essential component of exhibition content in science and technology museums

In addition to facing the challenge of presenting contemporary science and technology and research processes,science and technology museums also need to consider controversies arising in science (the biggest factor of uncertainty in scientific research) using a rational approach.For the research process itself,controversy is a necessary element in the advancement of science;however,for museums that wish to present this process,the complexity of dealing with controversies is far greater than when dealing with any complex history of science or scientific theories.

2.1.Controversies in science:An integral part of the scientific research process

Science centres have made useful explorations towards presenting the controversies accompanying the scientific research process.On the one hand,compared with natural history museums and science industry museums,which focus on historical artefacts and static displays,the biggest innovation of science centres is the hands-on experience of the scientific process that allows the visitors to see not just science ‘waiting to be discovered’.On the other hand,science centres are not constrained by existing collections.They can present the collisions of scientific views that have contributed to great scientific discoveries by way of storytelling,thus somewhat reproducing the controversies necessary for the creation of science and reinforcing the educational function of science history.

It is important to note that,whether through the simulation of scientific experimental processes or the narration of historical accounts of controversies in science,the essential function of science centres is to reorient science from its mature state to a more infant form,thereby leading visitors through a process similar to scientific research itself.Such similarity is,of course,both the result of the ingenious ideas of the designers and the continuation of the pedagogical traditions of science centres,which can be traced back to Jean Baptiste Perrin’s installation of the Palace of Discovery in 1937 (Ma,2017).However,the difference is that,although Perrin adapted scientific instruments to the needs of the visitors rather than the scientists,the adapted instruments appeared to be ‘close relatives’ of those used in scientific research at that time,whereas the exhibits in contemporary science centres are not even ‘distant relatives’ or ‘claimed relatives’ of the scientific instruments used in scientific research today but are more like the latter’s ancestors.Compared to books,the advantage of science centres lies in their ability to go beyond science ‘waiting to be discovered’.However,when the development of science centres cannot keep pace with the development of scientific research,it is much harder for them to portray the controversies in science.

2.2.Diverse controversies:Differences of science and technology themes

Macdonald conducted a case study of the scientific controversies presented in science museums based on an exhibition on food toxicity (Macdonald and Silverstone,1992).Through a comparative analysis of exhibits,scientists and visitors,she proposed emphasizing constructive properties in the presentation of scientific controversies -that is,controversies pertaining to real scientific research should not be directly reproduced in the exhibition hall,but the differences between the language of the exhibition and other media should be given due attention.John Durant has offered similar views about the presentation of contemporary biology in museums.While highlighting the uncertainty of contemporary science,he also advised that exhibition designers need to make more proactive choices in the interpretation process so as to achieve higher educational goals,such as arousing visitors’ curiosity,interest and attention,on the basis of faithful presentation of contemporary science and technology to the public (see Farmelo and Carding,1997).

A focus on the constructive properties of an exhibition and selecting suitable scientific content for exposition are not new academic ideas,but the presentation of scientific controversies has become more prominent.It is certainly important because it is a necessary stage of the scientific research process,and arguably even the most fascinating aspect of science,which makes it one of the central elements that must be addressed by museums.However,what are more important than the objectivity and neutrality of controversies are the unique properties of museum exhibitions in relation to other media,which require a focal controversy to be blended into a parent topic that is closely relevant to public life.Thus,while the priority dispute between Newton and Leibniz may be eye-catching due to its tabloid aspects,and the twisted plots of Einstein and Bohr’s debate over quantum physics are sufficiently many-sided to elicit a scientific epic,it is themes such as climate change and genetically modified food that have an enduring position in today’s scientific exhibitions,precisely because those exhibitions have reserved a proper place for the visitors in an ongoing scientific controversy.That said,the need to make choices has made it more difficult for museums to find a neutral place in exhibitions on scientific controversies,and scientific topics that are not ethically neutral in the first place are even more difficult to interpret.

2.3.Distinguishing between internal and external controversies:The stage of the scientific community and all society

Scientific controversies are first born within the scientific community,both as a necessary brainstorming process for scientists holding different views and ideas and as an essential path for great scientific discoveries.However,due to universal public engagement in the era of big science,some scientific topics that are closely related to people’s livelihoods often trigger heated public discussions -and even raise concerns about scientific research.For example,because the scientific mechanism of nuclear energy is not well understood,the public often tends to stay away from the sites of nuclear power plants -a response sometimes characterized as ‘not in my backyard’.Genetic modification is another example:with little knowledge about the applicable technology,the public hopes to know more about the possible adverse effects of the food they eat (even in the distant future).

Public controversies over scientific topics are often closely related to internal controversies within the scientific community.In the first instance,opposing views are expressed within the internal controversies.Then the potential social implications of those opposing views capture the public’s attention.However,considering the information barrier between the scientific community and the general public,many scientific issues that are still at the ‘controversial’ stage are not yet suitable for society-wide discussion,and premature public disclosure may even cause unnecessary misunderstanding about the science.For example,the ‘Zhu Haijun force’4may be a proper case for the scientific community to analyse the scientific process in the field of civilian science and scientific philosophy.However,if it is presented to the public through an exhibition,it will inevitably lead to misunderstandings among the visitors about acquired genetics.Thus,distinguishing between the controversies within and outside the scientific community is a fundamental ethical principle for science and technology museums (Li,2020).

For controversies within the scientific community,it is necessary to first make a judgement on whether the controversy involves ethical issues by gauging its impact on the well-being of human beings.For scientific controversies that are not ethical,it is necessary to present them to the public in a proper way as part of the process of scientific activities,thus presenting a more complete picture of science at the relevant museum.For scientific issues that clearly involve ethics,such as genetically modified food,nuclear energy use,climate change,genetic editing and big-data applications,it is necessary to choose appropriate content for such exhibitions and a means of presentation matched with the public’s understanding and acceptance.Moreover,in the part of an exhibition that presents the social impact of scientific issues and involves the public’s opinions,the public’s right to privacy must be given full attention (Canadian Museums Association,2006;ICOM,2017).

3.Coherence of tradition and innovation:Certainties and uncertainties of scientific knowledge

3.1.The science-centerization of science and technology museums:A trend towards the exhibition of non-consensual knowledge

Gregory and Miller (1998),in their bookScience in Public,contended that the science museums built at the end of the 19th century as well as some subsequent organizations have all followed the model of great science museums:they proudly display the nation’s technological progress and simultaneously describe the order of the nature;while presenting the material culture of science,they think more about generating benefits and creating inspiring and memorable exhibitions,and whether that helps to enhance public understanding is not as important.Notwithstanding this observation,shortly after the publication of their work,a large number of science centres sprang up in the UK,which paved the way for the science-centerization of the science and technology museum field and kept pace with the trend towards the presentation of contemporary science in the US (Li,2017).The science-centerization of science and technology museums is also taking place in the US:more and more science centres have been built across the country;while the number of traditional science and technology museums has been relatively stable,ever more of them have adopted interactive means of exhibition,as in science centres;some traditional science and technology museums have terminated their original functions,such as collecting and preserving historical objects,for a variety of reasons.

3.2.The ethical bottom line in the new era:A balance between old and new museum traditions

In science communication,it is always difficult to avoid definitions and choices.The contents ofcommunication with which the public engages in exhibition halls are not just scientific facts and processes,but also things that are regarded as science.The difference between museums and science centres lies not only in the form of presentation but also in the flexibility to select the contents.The fundamental difference between science exhibitions focusing on the past or the present is not so much the choice of historical artefacts or interactive installations but the choice of historical reflection or contemporary exploration as the way to see science.The curator does their work based on the collections or exhibits and always needs to balance between the traditional and new functions of the museum.5However,the science-centerization of science and technology museums has made the work of curators more complex,and so is the context they must be familiar with.Hence,the dynamic balance between tradition and innovation often needs to be achieved first within the curatorial community.

Table 1 reviews the evolution of the meaning of the word ‘curator’ in the context of museums,from a single keeper’s identity at the beginning to the addition of new identities.It is the increasingly complex identity of this key person in museums that has rendered the institutions’ ethical principles even more diverse.To answer the question ‘What principles do I need to follow?’,the first thing is to know who ‘I’ am.When digging into the cultural values of scientific history,it is important to know that all history is a reflection of the past in the contemporary context (Xu,2016);when presenting the uncertainties of contemporary science,it is necessary to consider the historical experience and heritage of scientific discoveries.Only by achieving such a balance will it be possible for museums to unearth which ethical concepts they should observe in a unified self-perception.

Table 1.Evolution of the meaning of the word ‘curator’.

3.3.Keeping ethical norms:Selfrepresentation in the process of museum research

As the New Museum Movement sweeps across the globe,greater numbers of museums have developed a self-consciousness with respect to cultural representation.In contrast,science and technology museums,which represent the latest scientific and technological progress,have clearly lagged behind.In China,more and more cities have built ‘city planning museums’,‘innovation museums’,‘city living rooms’ and other exhibition facilities to showcase the city’s future plans and technological strengths.The ‘civic cultural centres’ developed in recent years have become a large cultural representation system with the integrated functions of urban planning museums,museums,art museums,cultural museums,libraries,archives and science and technology museums.Under such a system,the museum complex is able to present the full picture of the city’s development plan,cultural heritage and scientific and technological strength -but science and technology as an independent cultural system and content has not been given adequate representation.

The certainty of scientific knowledge shows the impact of science in a particular historical period.It is the most visible feature that distinguishes science from other knowledge systems and underscores its superiority.On the other hand,the uncertainty of scientific knowledge,as one of the intrinsic properties of science,reflects science’s unique means of cognition and generates the cultural vitality of science.The ethical constraints of science and technology museums in their process of science communication do not come just from the scientific content itself.Rather,it is important to seriously consider whether the content and practice of communication are mutually consistent in their values within the exhibition and education process.For example,the Science Museum in London requires a rigorous ethical review of the research conducted in its galleries,and the deliberations of its ethics committee can take up to 6 months;the gallery management staff of the Deutsches Museum will stop any photo-taking with children in the picture and ask the photographer to delete the photograph on the spot.6The formulation and implementation of those rules are not outside of what the museum represents,but rather are an important part of the museum’s self-representation of its ethical concepts.As cultural producers,museums are increasingly required to be original in their presentation of scientific contents,which in turn leads to growing ethical responsibilities in the process of science communication.

4.Conclusion

Both the New Museum Movement and the sciencecenterization of traditional science and technology museums bring with them ideas that increase the requirements of cultural definition and representation for museums.When traditional science and technology museums operate as non-formal educational institutions,they need to follow a uniform code of communication and educational ethics.However,alongside the growing emphasis on a museum’s properties as a site of cultural representation,the complexity of the ethical issues in the definition and representation of scientific culture also increases dramatically.Uncertainty,which is an intrinsic property of science,is both an inescapable component of scientific culture and an area in which the ethical issues of science communication concentrate.It has thus become a unique challenge for science and technology museums in comparison to other types of museums.Accordingly,the ethical issues faced by science and technology museums in the process of science communication come in two parts:the common ethical issues for the whole museum community,and the distinctive ethical issues generated by specific scientific topics.Having attained a higher level of cultural discourse,it is only natural for science and technology museums to now consider how they can create a unique scientific culture from the museum perspective and deal with the dual challenges of representing the ethical norms of science and practising the ethical norms of museums.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,authorship,and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research,authorship,and/or publication of this article.

Notes

1.The term ‘science and technology museums’ used in this paper refers to museums that focus on science,technology and industry,and includes both science and technology museums and science centres(Alexander and Alexander,2014;Li,2018).

2.The term ‘museumization’ in this paper refers to the reorganization process that turns materials and information outside museums into museum properties,including but not limited to collection,preservation,research and display activities.Museumization is a concept frequently used in museum studies today(see,e.g.Dong and Hou,2020;Yan and Mao,2020).

3.According to Li’s research,the museum is primarily used for research by students and faculty of the University of California,Berkeley,and differs significantly from contemporary museums that are often used as public spaces.

4.‘Zhu Haijun force’ is a hypothesis about human evolution proposed by Chinese civilian science enthusiast Zhu Haijun.He offered a fantastic explanation for human walking upright:the unique face-to-face sexual position made humans stand up upright.

5.Information from Li’s interview with Deborah Douglas,curator of the science and technology collections at the MIT Museum in Cambridge,Massachusetts.

6.Data collected from Li’s field survey of the two museums and an interview with Laurie Michel,a staff member at the Science Museum in London.