A systematic review of dedicated models of care for emergency urological patients

Ned Kinner ,Mtheesh Herth ,Dyln Brnett ,Derek Hennessey ,Christopher Doins ,Trik Smmour ,Jmes Moore

a Discipline of Surgery,Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences,University of Adelaide,Adelaide,Australia

b Department of Surgery,Royal Adelaide Hospital,Adelaide,Australia

c Department of Urology,Mercy University Hospital,Cork,Ireland

KEYWORDS Acute surgical unit;Acute care surgery;Urology;Emergency;Acute;Dedicated

Abstract Objective: To systematically evaluate the spectrum of models providing dedicated resources for emergency urological patients (EUPs).Methods: A search of Cochrane,Embase,Medline and grey literature from January 1,2000 to March 26,2019 was performed using methods pre-published on PROSPERO.Reporting followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and meta-analysis guidelines.Eligible studies were articles or abstracts published in English describing dedicated models of care for EUPs,which reported at least one secondary outcome.Studies were excluded if they examined pathways dedicated only to single presentations,such as torsion,or outpatient solutions,such as rapid access clinics.The primary outcome was the spectrum of models.Secondary outcomes were time-to-theatre,length of stay,complications and cost.Results: Seven studies were identified,totalling 487 patients.Six studies were conference abstracts,while one study was of full-text length but published in grey literature.Four distinct models were described.These included consultant urologists allocated solely to the care of EUPs (“Acute Urological Unit”) or dedicated registrars or operating theatres (“Hybrid structures”).In some services,EUPs bypassed emergency department assessment and were referred directly to urology (“Urological Assessment Unit”) or were managed by other dedicated means.Allocating services to EUPs was associated with reduced time-to-theatre,length of stay and hospital cost,and improved supervision of junior medical staff.Conclusion: Multiple dedicated models of care exist for EUPs.Low-level evidence suggests these may improve outcomes for patients,staff and hospitals.Higher quality studies are required to explore patient outcomes and minimum requirements to establish these models.

1.Introduction

Emergency urological patients (EUPs) represent a significant patient cohort in clinical practice.They comprise >2%of emergency department presentations [1—3] and up to 30% of all urology inpatient admissions [4].Traditionally,these patients have been assessed and managed ad-hoc.Urological surgeons and trainees were rostered during business hours to elective duties,with EUPs seen inbetween or afterwards.This created predictable inefficiencies,including delays for both acute and elective patients and frequent after-hours operating,which are detrimental to patients and surgeons [5—7].

In general surgery,discontent with similar conventional structures led to the introduction of the acute surgical unit(ASU) [8,9].A central component of the ASU model is a dedicated surgeon allocated for emergency general surgery patient care.Additionally,trainees may be rostered to staff the ASU service and quarantined emergency operating theatres made available.The model is associated with reduced time to theatre,reduced operating after-hours,fewer complications and shorter length of stay [10,11].In urology,increasing numbers of emergency patients have led to calls for similar reform [1,12,13].However,innovation for EUPs remains in its infancy,and there is a relative dearth of data on this topic.There are no systematic reviews on these dedicated models of care for EUPs.

In this review,we aim to describe the spectrum of dedicated models of care for EUPs published in the literature.We hypothesize that these systems will improve the timeliness of care and be equivalent or superior in other measures.

2.Methods

2.1.Search strategy

A systematic search of Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL),Embase and Medline was conducted in April 2019.Searches limited studies to the period January 1,2000 and March 26,2019,and utilized Boolean operators as follows:(OR:Acute care urol,acute care surg*,acute urol*,acute surg*,emergency urol*,emergency surg*,surgical assessment,dedicated,protected) and (OR:Department,pathway,program,service,system,team,unit) and (OR:Urology,urological).

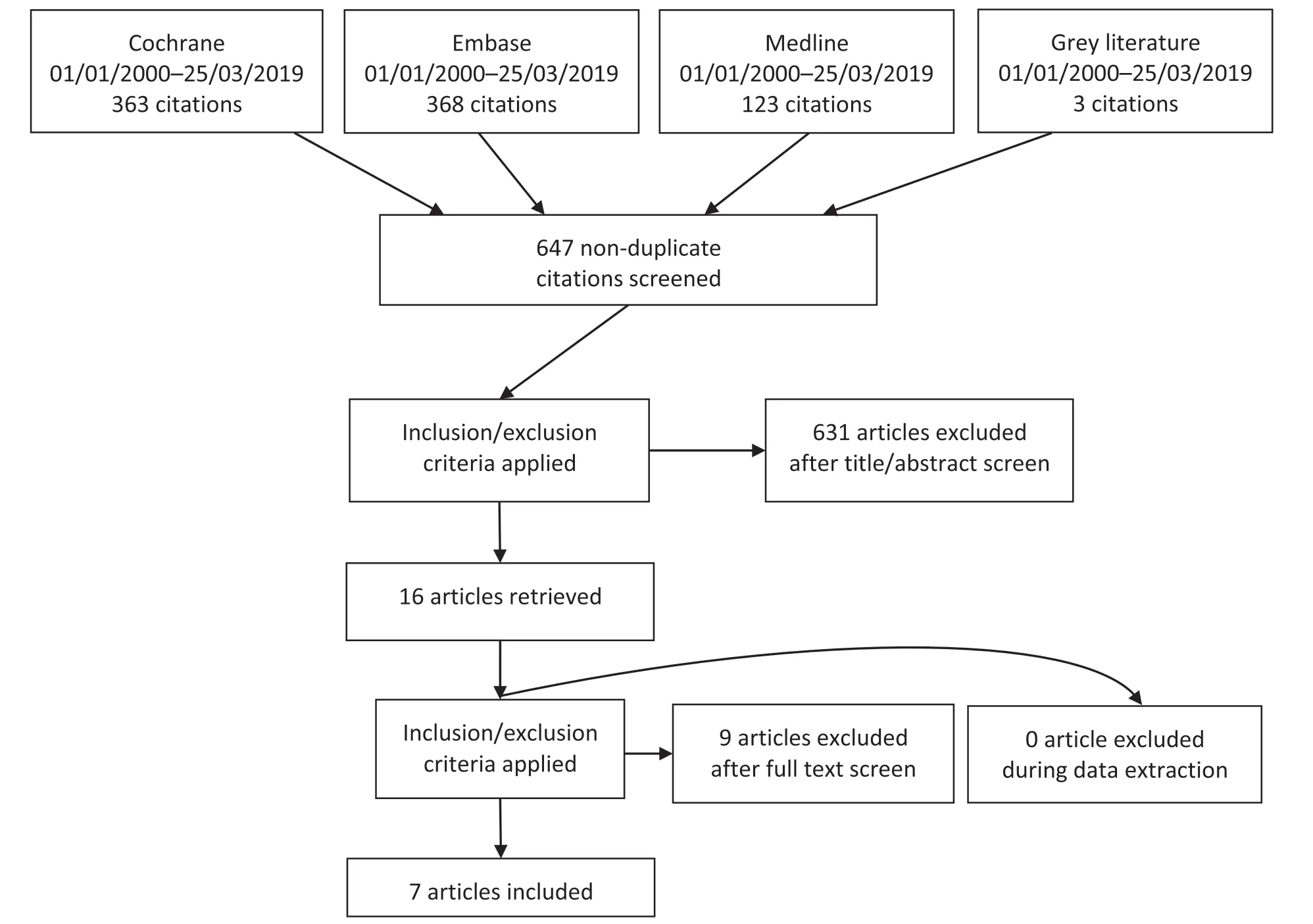

Grey literature was also assessed.This included allowing the inclusion of relevant unpublished studies (including conference abstract proceedings)that were identified in the above database searches,and reviewing the bibliographies of eligible studies.The list of retrieved studies is available in Appendix 1.The process for identifying and evaluating data complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-analyses criteria [14] (Fig.1).This included pre-publication of our intended search method analysis on PROSPERO (CRD42019130225).Identified studies were screened sequentially by title,abstract and full-text review,with ineligible results removed at each step.Eligible studies then underwent data extraction and review of references.Two authors(Kinnear N and Herath M)independently screened results and performed data extraction,using a pre-defined form (Appendix 2).For accuracy,data were extracted twice.Disagreements were resolved by discussion.There was a consensus amongst all authors concerning the inclusion criteria and the final list of included articles.

2.2.Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Criteria for study eligibility followed the patient population,intervention,comparator,outcome and study method(PICOS) [14].Eligible studies assessed EUPs (P),had a cohort receiving care from dedicated resources (I),may or may not have utilized a comparator group(C)and reported outcomes from a sample of solely EUPs on at least one of timeliness of care,length of stay,complications or cost(O).Eligible studies were original and published in English (S).The first studies allocating resources to emergency general surgical patients were published in 2001 [8],with subsequent consideration of urological versions.While there have been successful examples of pathways introduced to expedite care for patients with specific presentations,such as renal colic [15,16] or acute scrotum [17],these do not offer benefit to the majority of EUPs.Hence,studies were excluded if they were published before the year 2000 or in a language other than English,failed to describe at least one outcome from a sample of purely EUPs,or documented pathology-specific or outpatient solutions,such as torsion or rapid access clinics,respectively.

2.3.Intended analyses

The primary outcome was the spectrum of models.Secondary outcomes were time to theatre,length of stay,complications and cost.All relevant studies were summarized qualitatively.We anticipated finding insufficient studies for quantitative assessment,so this was not planned.However,studies with similar models of care were presented together.The Acute Urological Unit was defined as one in which a consultant urologist was dedicated each day to EUPs,without elective or private commitments.A hybrid structure did not meet this requirement but benefited from either a urology registrar allocated solely to emergency patients or protected operating theatre access.Distinct from these options,services which managed EUPs without the involvement of emergency department physicians were classified as Urological Assessment Units.Services separate from the above three categories were described individually.If instances of unreported results were encountered,such as absent patient sample size,at least two attempts were made to contact study authors by email to clarify.

2.4.Bias

Tools to assess study quality were tailored to study design[18].The authors did not expect to identify any randomized controlled trials.Subsequently,risk of bias for (comparative) cohort studies was assessed utilizing the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale,as prescribed by the Cochrane Handbook[19,20].For non-comparative case series,study quality was measured with the modified Delphi checklist,as recommended by a recent systematic review of quality assessment tools [21,22].Given the expected nature of included studies,three of nine items on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale were inapplicable and not scored,as were three of eighteen modified Delphi criteria.Study quality was independently assessed by two reviewers (Kinnear N and Herath M)against pre-defined criteria (Appendix 3).Disagreements were resolved by discussion.Risk of bias was not used to exclude studies.We anticipated identifying too few studies to assess publication bias.

3.Results

Figure 1 Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram.

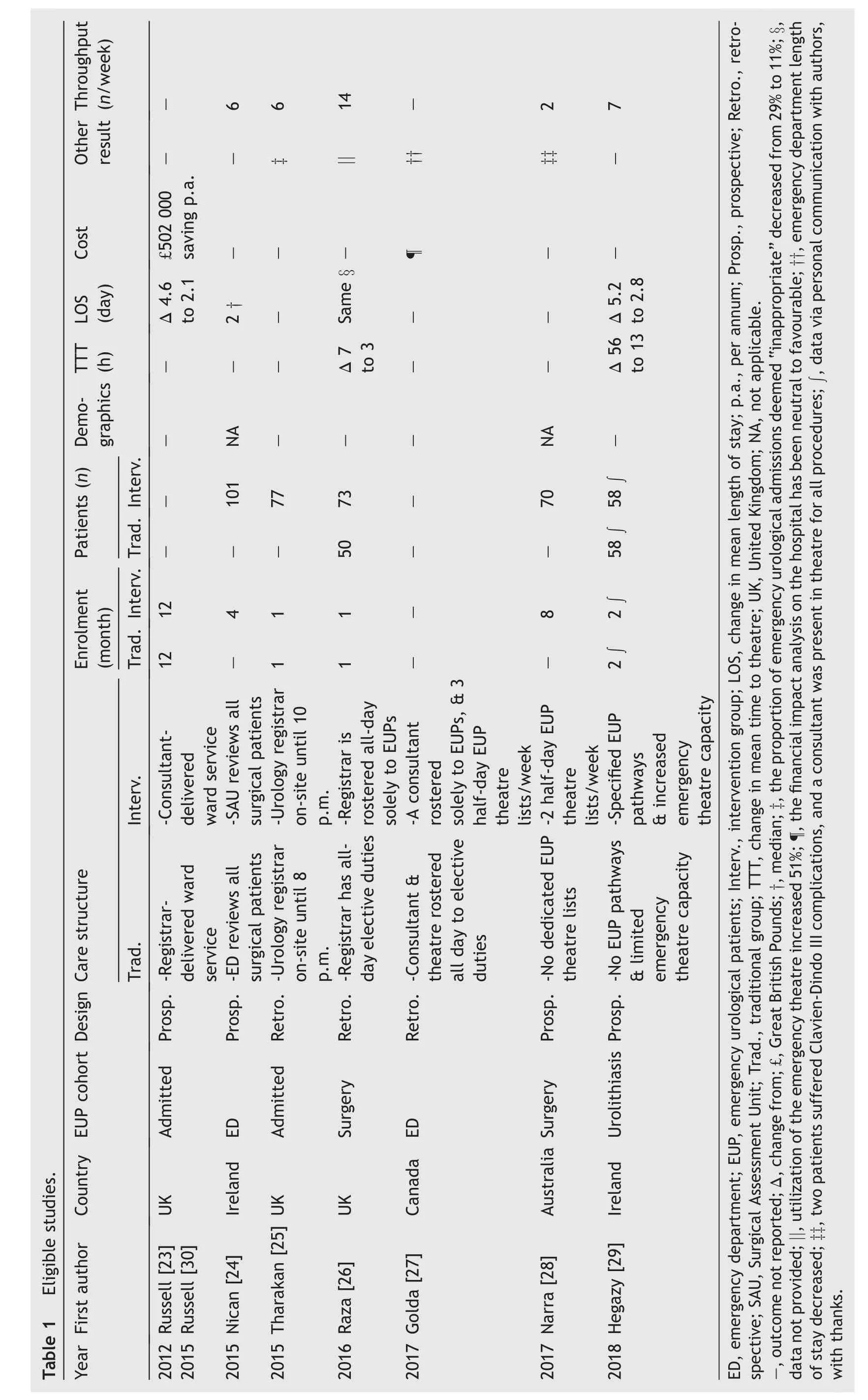

A total of 854 studies were found on database searches,with an additional three identified from bibliographies and other grey literature (Fig.1).After removal of 210 duplicate results and 631 irrelevant studies,16 articles were retrieved for full-text review (Appendix 1).From these,seven eligible publications were selected,totaling 487 patients [23—30] (Table 1).However,this sum represents an under-estimate,with three studies reporting samples of undefined size.All publications were nonrandomized single-centre studies.Only one full-length article met the eligibility criteria [30].This was published in grey literature (electronic bulletin) and not indexed on the pre-specified databases.All other studies were available as abstract only,representing a low level of evidence.Database searches were performed for all authors of all included studies but did not reveal any instances of these abstracts proceeding to full-text articles.

3.1.Study design

Two included studies were non-comparative case series of patients following introduction of dedicated emergency urological services [24,28],while the remaining five were comparative cohort studies,describing patient groups before and after such changes [25—27,29,30].Four studies were prospective [24,28—30],and three retrospective[25—27].There was a substantial disparity in the studies’chosen enrolment moment within the patient journey.Two studies each assessed EUPs who had either presented to the emergency department [24,27],been admitted [25,30] or proceeded to the theatre[26,28],while one study assessed those with symptomatic renal calculi requiring surgery[29].Similarly,patient enrolment period varied from 2 to 24 months [24—26,28,30],with two studies not reporting duration[27,29].No studies described the use of statistical tests orp

-values.

3.2.Primary outcomes

Four distinct dedicated models of care for EUPs were observed(Table 1).Two studies described introducing Acute Urological Units,with a consultant urologist allocated solely to EUPs [27,30].Russell et al.[30] reported the commencement of a daily ward round of all inpatients and referrals,while Golda et al.[27] assessed the creation of a full time position dedicated to EUPs,both staffed from a rotating pool of urologists.The latter also included three half-day operating lists per week allocated to EUPs.Three publications reported establishing Hybrid models of care for EUPs.Raza et al.[26]described amending rosters to provide an full day urology registrar for emergency patients,while two other studies introduced protected emergency urology operating theatre access of either two half-day lists per week or unspecified quantity[28,29].The commencement of a Surgical Assessment Unit was documented by Nican et al.[24],within which emergency patients with suspected surgical diagnoses (including general surgical,urological and other) were triaged directly to dedicated “senior” surgical staff,bypassing the emergency department.Lastly,Tharakan et al.[25] described a separate solution.In a service traditionally placing responsibility for assessing and admitting EUPs on senior house officers not yet in formal urological training (e.g

.“un-accredited” registrars),this study introduced extended on-site evening shifts for accredited urology registrars to supervise the process.3.3.Secondary outcomes

3.3.1.Time to theatre

Two studies reported decreased time to theatre for EUPs following commencement of hybrid services.Compared with conventional models,mean time to theatre decreased from 7 h to 3 h in one study including all EUPs[26],and from 56 h to 13 h in another assessing only those with symptomatic urolithiasis [29].

3.3.2.Length of stay

Four studies reported data on length of stay.Mean length of stay decreased in one study from 4.6 days to 2.1 days for all EUPs following the introduction of an Acute Urological Unit model [30],and from 5.2 days to 2.8 days amongst renal colic patients after the establishment of a Hybrid structure[29].In a separate study,the commencement of a hybrid structure did not alter the length of stay (data not provided) [26].A non-comparative case series of EUPs of any diagnosis treated within a Surgical Assessment Unit reported a median length of stay of 2 days [24].

3.3.3.Cost

Two studies of acute urological units reported financial results.In 2012,a study from the United Kingdom extrapolated reductions in length of stay to estimate annual savings of £502 000 for an “average district general hospital” [30].Separately,a Canadian study of unspecified enrolment duration stated that “the financial impact analysis on the hospital has been neutral to favourable”,without providing further data [27].

3.3.4.Other findings

Eligible publications sporadically reported various hospital,patient and staff outcomes.Regarding benefits to hospitals,Golda et al.[27]observed that establishment of their Acute Urological Unit was associated with reduced emergency department length of stay (data not stated) [27].One cohort study describing the introduction of a hybrid model with a dedicated registrar for EUPs found emergency theatre utilisation improved by 51% [26].Separately,in a service where the after-hours assessment of EUPs was the responsibility of more junior house officers,extending accredited urology registrar shift duration was associated with the proportion of emergency urological admissions deemed preventable decreasing from 29% to 11% [25].Regarding patient outcomes,a non-comparative case series of EUPs undergoing surgery found that following commencement of a Hybrid model,a urologist was present in theatre for all cases and only 3% of patients suffered Clavien-Dindo Grade III-IV complications [28].

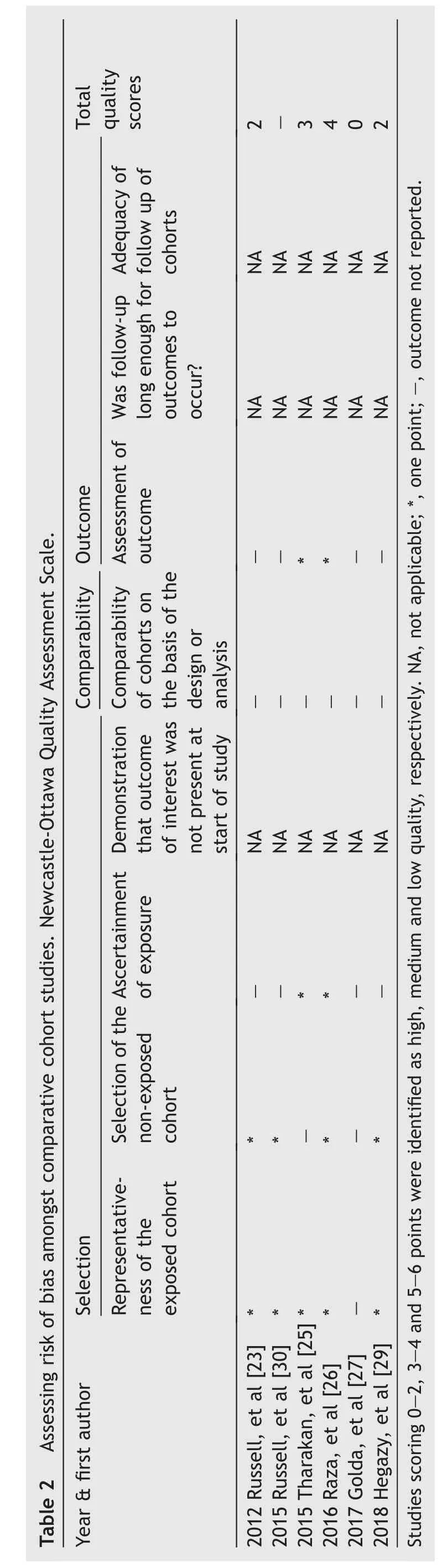

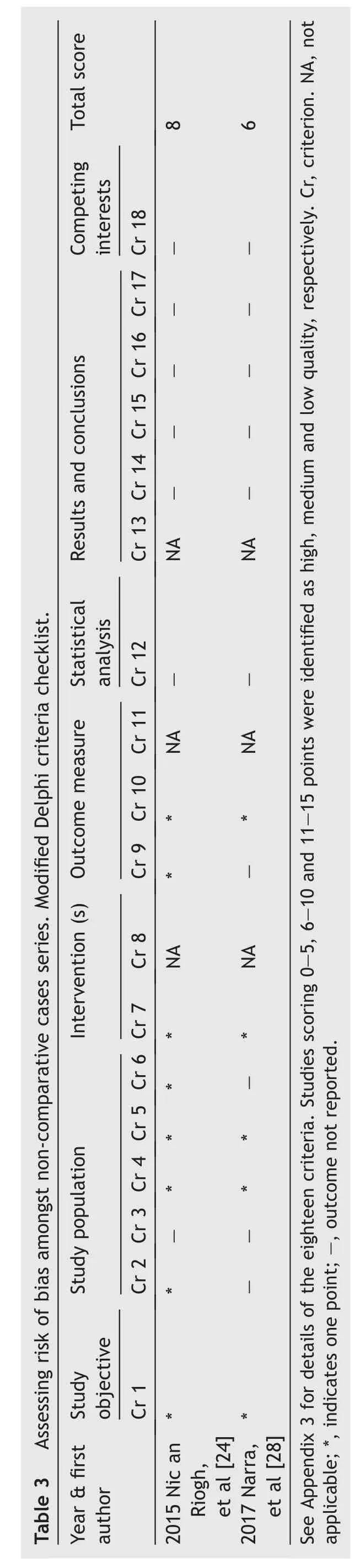

3.4.Assessment of bias

The existence of eligible research in predominately abstract form substantially hindered assessment of bias,as descriptions of method were very limited.Utilizing the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale,the risk of bias was medium to high for the five comparative cohort studies (Table 2).Similarly,the modified Delphi criteria suggested the two non-comparative case series were of only medium quality(Table 3).None of the seven studies described the presence or absence of patient exclusions,ethics approval,conflicts of interest or funding.Reporting bias may be present,with only one study providing data on complications [28].Publication bias was not assessable due to the low number of similar studies.

4.Discussion

Modern efforts to pro-actively allocate resources to emergency surgical patients began in general surgery >20 years ago [8—10].The driving forces behind this modernization were significant need and sufficient staff pool to allow restructuring.General surgery’s elective activities within traditional models of care were particularly prone to interruption,due to caring for more than twice as many emergency patients as any other surgical specialty [31].Local forces such as governmental targets to limit patient time in the emergency department have also incentivized surgical staff allocation to emergency patients [32,33].Additionally,there are more general surgeons than any other type [34],providing capacity to dedicate separate personnel in the ASU model.It is anticipated that these models will spread to other surgical specialties when similar patient and staff number are reached.Furthermore,this type of restructuring may benefit emergency patients in urology more than other sub-specialties,as evidence suggested EUPs suffer the greatest delays while awaiting theatre [35].

This first systematic review of dedicated models of care for EUPs suggested that they may offer many benefits.Patients may experience reduced time to theatre and length of stay.The mean time to theatre decreased from 7 h to 3 h in one study including all EUPs and from 56 h to 13 h in another assessing only those with symptomatic urolithiasis [26,29].Mean length of stay decreased in from 4.6 days to 2.1 days for all EUPs and from 5.2 days to 2.8 days amongst renal colic patients following the introduction of an Acute Urological Unit and hybrid model,respectively[29,30].In one study,this resulted in an estimated annual savings of £502 000 (USD $632 000) [30].Finally,junior doctors may enjoy greater supervision both in the emergency department and operating theatre [25,28].

From the above it is clear that dedicated emergency urological models of care may be beneficial for both patients and hospitals.Further demonstration of the spread of these structures is provided by full-text articles which did not meet inclusion criteria.In the United Kingdom,Mohamed and Mufti [36] presented an eight-week audit of their Surgical Assessment Unit.While their sample included 119 EUPs,no outcomes were given for this sub-group.Separately,a French language case series described 1257 patients treated in their Acute Urological Unit in 2009[37].

A urological department considering introducing dedicated models of care for EUPs must assess their EUP load,staff pool and implications for training.Included studies observed benefit from dedicated models implemented in centres with annual EUP load of approximately 500 admissions [30] and about 300 procedures [24].They suggested the minimum required number of urologists was five to six[27,30],identical to the number of general surgeons reported necessary to staff an ASU [8,38,39].While none of the identified urological studies described barriers to change,insight may continue to be gained from general surgery.Amongst hospitals without dedicated models for emergency general surgical patients,reported concerns to their introduction include insufficient patient load or surgeon pool and beliefs that patients with complex emergencies such as perforated diverticulitis will receive superior care in sub-specialty rather than ASU on-call systems [39,40].Hospitals which have implemented an ASU have rarely reported disadvantages.However,those described include the requirement for on-call consultants to hold no elective duties creating difficulty in roster swaps,and anecdotal reports that the remuneration for ASU practice does not cover income lost in forfeiting other activities [41].Additionally,ASU start-up funding is typically required before subsequent potential cost-neutrality or savings may be realized [42,43].Finally,the identified studies provide limited evidence that dedicated models of care benefit urological trainees,insofar as increased supervision [25,28].

This review is limited by the low level of evidence of the eligible studies,and its findings should be interpreted with substantial caution.All included studies have been subjected to only the scrutiny required for conference presentation or electronic bulletin inclusion,with none undergoing formal journal peer-review.Small or unreported sample sizes and lack of any statistical analyses further undermine these studies.

4.1.Conclusion

This review demonstrates early attempts within urology to emulate the successes of general surgeons in pre-emptively allocating resources to emergency presentations.It provides low-level evidence that similar models in urology may improve outcomes for patients,staff and hospitals.Further studies are needed to assess comparative patient and financial outcomes and establish the minimum requirements of these models.

Author contributions

Study concept and design

:Ned Kinnear.Data acquisition

:Ned Kinnear and Matheesha Herath.Data analysis

:Ned Kinnear and Matheesha Herath.Drafting of manuscript

:Ned Kinnear,Matheesha Herah,Dylan Barnett,Derek Hennessey,Christopher Dobbins,Tarik Sammour,James Moore.Critical revision of the manuscript

:Ned Kinnear,Matheesha Herah,Dylan Barnett,Derek Hennessey,Christopher Dobbins,Tarik Sammour,James Moore.Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Adelaide Graduate Centre of the University of Adelaide.Ned Kinnear received a University of Adelaide divisional scholarship (UoA2018),a Hospital Research Foundation post-graduate scholarship(2018/6330) and a National Health and Medical Research Council post-graduate scholarship (1169487) in relation to this work.

Appendix A.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2020.06.006.

Asian Journal of Urology2021年3期

Asian Journal of Urology2021年3期

- Asian Journal of Urology的其它文章

- Testing for BRCA1/2 and ataxiatelangiectasia mutated in men with high prostate indices:An approach to reducing prostate cancer mortality in Asia and Africa

- Male genital damage in COVID-19 patients:Are available data relevant?

- A comparison of artificial urinary sphincter outcomes after primary implantation and first revision surgery

- Augmented anastomotic urethroplasty with buccal mucosa for post penile fracture urethral injury long segment bulbar urethral stricture review

- The neutrophil-tolymphocyte ratio at the prostate-specific antigen nadir predicts the time to castration-resistant prostate cancer

- Conquering new battlegrounds:Successful management of isolated giant retrovesical hydatid cyst with robotic assistance