Challenges and optimization strategies in medical imaging service delivery during COVID-19

Yi Xiang Tay, Suchart Kothan, Sundaran Kada, Sihui Cai, Christopher Wai Keung Lai

Yi Xiang Tay, Sihui Cai, Radiography Department, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore 169608, Singapore

Suchart Kothan, Center of Radiation Research and Medical Imaging, Department of Radiologic Technology, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50000, Thailand

Sundaran Kada, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Bergen Postbox 7030, 5020 Bergen, Norway

Christopher Wai Keung Lai, Department of Health and Social Sciences, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore 138683, Singapore

Abstract In coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), medical imaging plays an essential role in the diagnosis, management and disease progression surveillance. Chest radiography and computed tomography are commonly used imaging techniques globally during this pandemic. As the pandemic continues to unfold, many healthcare systems worldwide struggle to balance the heavy strain due to overwhelming demand for healthcare resources. Changes are required across the entire healthcare system and medical imaging departments are no exception. The COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating impact on medical imaging practices. It is now time to pay further attention to the profound challenges of COVID-19 on medical imaging services and develop effective strategies to get ahead of the crisis. Additionally, preparation for operations and survival in the post-pandemic future are necessary considerations. This review aims to comprehensively examine the challenges and optimization of delivering medical imaging services in relation to the current COVID-19 global pandemic, including the role of medical imaging during these challenging times and potential future directions post-COVID-19.

Key Words: COVID-19; Medical imaging service; Pandemic; Optimization strategies;Radiology department; Radiography

INTRODUCTION

A cluster of unknown pneumonia cases was reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province,China on December 31, 2019. There were both similarities and differences in various aspects of this pathogen with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) that originated in China’s Guangdong Province on November 27, 2002[1]. Despite the difference in epidemiology, like SARS, it presented as a respiratory disease which was officially named and announced by the World Health Organization (WHO) as“COVID-19” (coronavirus disease 2019), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[2]. Most patients infected with COVID-19 had pneumonia and hence medical imaging became vital in the early diagnosis and assessment of disease course[3]. Moreover, the medical imaging role in an infectious disease outbreak had been well described and was epitomized by the SARS epidemic[4]. While the use of medical imaging techniques—chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) differed across countries, there was no doubt about the significance and importance of medical imaging in this COVID-19 pandemic[3,4]. The aim of this review is to highlight the challenges and optimization strategies in medical imaging service delivery in Singapore and around the world during this COVID-19 pandemic.

ESSENTIAL ROLES IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF COVID-19: CHEST RADIOGRAPHY AND CT

Chest radiography played an important role in the diagnosis of SARS during the 2003 outbreak in Hong Kong[5,6]. Despite poor sensitivity, patients with clinical and epidemiologic suspicion of SARS were evaluated by serial chest radiography[7]. A similar practice of serial chest radiography was also adopted in Singapore (together with Hong Kong, one of the 10 countries with the most cumulated numbers of cases)[8,9]. This practice included chest radiography for patients with contact history who had developed respiratory symptoms, even if afebrile, when person-to-person transmission was evident globally[5]. In fact, this was in line with the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendation at that time[5].

With the global resurgence of person-to-person transmission in the form of COVID-19, the sense of Déjà vu was vivid. During this pandemic, despite the trajectory use of CT scan in China as a screening tool[10], most radiology societies still do not endorse routine screening CT for COVID-19 pneumonia[11,12]. Although the WHO rapid advice guide for the use of chest imaging in COVID-19[13] highlighted considerations for choice of imaging modalities, it stopped short of recommending specific imaging modalities for different categories of patients. This could be attributed to the different community norms and public health directives[14].

Chest radiography was of greater value in patients with advanced symptoms as compared to those in the early course of their disease[14,15]. For patients who were encouraged to present once symptomatic, as was the case in Wuhan, China, chest radiography had little value as it was insensitive in mild or early COVID-19 infection[14-16]. In a similar vein, Singapore also had the public health directive for citizens to consult a doctor even when they had mild respiratory symptoms[17].However, in Singapore, chest radiography remains the primary imaging modality of choice in COVID-19 screening, with a CT scan used only as a problem-solving tool[4,18]. On the other hand, some countries such as South Korea uses reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for initial screening instead of relying on diagnostic imaging studies[19]. Nevertheless, chest radiography is a fundamental tool in the diagnosis, management and monitoring of disease[20-22].Moreover, chest radiography is widely available (less resource intensive), coupled with features of rapid execution, low cost and function of bedside radiography. This enables chest radiography to be an important complement to clinical and epidemiological features in the battle against COVID-19[13,22].

On the other hand, although a CT scan has relatively low specificity, it has a relatively higher sensitivity as compared to chest radiography and RT-PCR[10,13].This is useful in patients with some pre-existing pulmonary diseases and when results of RT-PCR tests are negative[10,13,14]. While there were differing views on the first assessment medical imaging technique for COVID-19 infection, there was no doubt of the importance of medical imaging services in the battle against COVID-19. Considerations on the choice of medical imaging technique were usually dependent on local practice patterns and resource availability[14].

Nevertheless, as mentioned in the multinational consensus statement from the Fleischner Society[14] — the choice of medical imaging techniques should be based on the clinical judgement of the clinical teams while considering the attributes of the techniques, local resources and expertise. In addition, the involvement of all stakeholders — referring clinician, radiologist and patient, in the decision-making on the choice of medical imaging of COVID-19 was encouraged[13]. Similarly, whenever possible, the patient should be provided with information on the chosen medical imaging techniques and the potential of the multiple imaging requirement highlighted[13].

CHALLENGES IN THE PROVISION OF MEDICAL IMAGING SERVICE DURING COVID-19

Limited manpower

Maintaining a healthy and adequate workforce is crucial in any infectious disease epidemic. Moreover, with screening, monitoring and evaluation roles undertaken by radiology in this COVID-19 pandemic, managing manpower was even more important. Given that more COVID-19 patients were being admitted and enough manpower would be required to meet the demands of increased workload, ensuring functional staff for continued service should not be undermined[23].

Within a month (January 30, 2020) after the first reported confirmed case of SARSCoV-2, there were 82 confirmed cases outside of China with the majority of cases reported in Asia[24]. The WHO subsequently released its strategic objectives for the pandemic which included early identification, isolation and care of patients, including providing optimized care for infected patients[25]. Clearly, a substantial number of staff was required in response to this new infectious disease, especially when there was unprecedented numbers of people diagnosed with COVID-19 and seeking treatment.

At the early onset of the battle against COVID-19, Singapore faced the possibility of the healthcare system being overwhelmed. The Singapore Ministry of Health responded to the threat by initiating an island-wide call for former healthcare professionals (HCPs) to support the country’s fight against the coronavirus, including doctors and allied health professionals[26]. A similar picture was seen globally, where retired doctors, nurses and medical students were mobilized to join the fight[26-30].

As the pandemic unfolded, many radiology departments experienced an increase in manpower demand due to many factors which included the increase in workload, and procedure time and the impact of team segregation[4,31,32]. A similar experience was also reported in low resource settings such as Ghana and Iran, although some regions reported a decline in general workload, in line with reports from North America and Europe, which could be attributed to low COVID-19 case intensities in these regions[33,34]. Nonetheless, it was well established that the healthcare workforce was facing high adversity and workload as more countries were impacted by the spread of COVID-19[35].

To respond to the sudden surge and new waves of COVID-19, the radiology workforce had to be redeployed or re-assigned to other imaging modalities[33,36-38].In tandem with the call for former HCPs, there was a need to reskill and/or upskill the returning workforce to support the current workforce. Clearly, a substantial amount of time had to be invested in creating training opportunities for staff to be prepared to face the pandemic. However, that would result in hours away from the clinical environment. Indeed, it was suggested that tens of thousands of radiographer hours would be invested to develop information to help radiographers worldwide to manage the imaging of COVID-19 patients using mobile chest radiography with appropriate infection control measures[39]. Notwithstanding, there was also the potential of the massive amount of replication of information globally while attempting to address this information deficiency[39]. Moreover, departments had to grapple with understaffing at the peak of the outbreak due to HCPs infections, selfisolation due to contact with positive cases and statutory paid sick leave in many countries globally[40].

Enhancement of infection control measures

In a radiology department, radiographers may be exposed to SARS-CoV-2 during mobile radiography and chest CT procedures. As these procedures were more often performed as part of routine diagnosis, assessment and monitoring of the disease,there was an increased risk of radiographers contracting COVID-19[41]. In addition,procedures with prolonged patient contact such as ultrasound and interventional radiology expose radiology staff to an even higher risk of infection[41-44]. At the same time, radiology services are a crossroad of heterogeneous subjects within hospitals;measures had to be taken to mitigate the risk of the radiology workforce being infected to protect other HCPs, patients and the general public[41,45].

It is well established that the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of training in infection control measures, and poor PPE usage increase the risk of patient-HCP transmission of infection[46,47]. Indeed, the provision of adequate PPE is of paramount importance and is a critical component of infection control and prevention during this pandemic. However, globally, many departments were facing a shortage of PPE[48]. In fact, multiple reports of shortages of PPE, medical supplies and COVID-19 test kits had surfaced in various countries ranging from developing countries in Southeast Asia to developed countries like the United States[49,50]. This was worrying as previous lessons from other infectious disease outbreaks had identified PPE as a crucial element in reducing infections and deaths of HCPs[47].During this pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 infection among HCPs was not unheard-of. China and Italy both reported infections and deaths of HCPs[50,51], while United States[52],Spain[46] and Qatar[53] all reported COVID-19 infection among its HCPs. This could lead to a decline in the healthcare workforce, resulting in unstable healthcare infrastructure, thus reducing the quality and quantity of care available while increasing the workload on remaining staff[47,54].

Although ensuring that HCPs are well protected is crucial in reducing viral transmission and sustaining health system capacity[47], equipment used in the radiology department is also a potential vector for transmission of the virus. Identified equipment include ultrasound units, non-portable modalities, such as CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and mobile radiography units[31,41,43,55,56]. The immerse challenge for infection control in the CT suite was epitomized in China where CT was often the first-line investigation for COVID-19[15]. The equipment had to be disinfected after exposure according to recommended guidelines by the vendors or institutions. Similarly, accessories such as keyboards, mice, viewing stations and blood pressure cuffs had to be disinfected accurately with appropriate and safe disinfectant[57,58]. Clearly, all potentially contaminated surfaces had to be disinfected to reduce the risk of virus transmission.

Limited resources

Provision of medical imaging services to many patients suspected of having or confirmed to have COVID-19 during the pandemic was a herculean task. The procedure duration was lengthened and complicated by strict infection control measures to mitigate infection risk in the radiology department[14,41,59]. This was highlighted by the American College of Radiology (ACR)[60] where it noted that CT decontamination after scanning COVID-19 patients might disrupt radiologic service availability. Studies sharing recommendations for infection control in the CT suite were widely available. However, it also demonstrated the substantial time and resources needed during, pre- and post-CT scans, which was highlighted by the ACR[57,61,62]. While hospitals with more than one scanner could dedicate one scanner for scanning COVID-19 patients, it could not be instituted in all hospitals[63,64]. Therefore, in this pandemic, in some countries, CT cannot be superseded by chest radiography due to limited scanners[15].

To mitigate the limitation, coupled with long turnaround times for RT-PCR,countries such as Italy and United Kingdom had adopted chest radiography as a firstline triage tool[15]. This could also be attributed to the favourable feature of a mobile unit — portability, where chest radiography could be performed at the bedside instead of transporting the patient to the scanner[14]. This effectively reduced patient transfer and minimized the risk of cross-infection to others[13,55]. Given the obvious benefit of mobile chest radiography, the uptake and demand of chest radiography as a first-line assessment tool would increase over time. This posed a challenge to even a large hospital — where Singapore’s largest acute tertiary referral medical centre had to acquire additional mobile units to meet the increasing clinical demands[55]. A similar challenge was also noted in South-East Queensland, Australia where purchase, rapid acquisition and deployment of additional mobile units were initiated[65].

However, with the urgent delivery and growing orders for mobile units, some vendors could not meet the urgent delivery timeframe[66]. Against this backdrop,many hospitals in England were struggling with equipment shortage and backlog[67].Many were in urgent need of more staff and imaging equipment — CT, MRI,ultrasound and mobile units, to deal with backlog cases. It was particularly vivid in the United Kingdom where it was reported to have the lowest number of scanners when compared with other Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries[67]. This resulted in a significant block capacity gap within the United Kingdom, prompting The Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) to describe the situation as a perfect storm in terms of delivering capacity[67].

Faced with the challenge of limited delivering capacity and mounting wait lists,patient access to medical imaging services was profoundly affected. This was evident in Canada where waiting time for medical imaging is now twice as long when compared with pre-COVID times — significantly beyond the acceptable standards[68]. A similar picture was painted in the UK where statistics had highlighted the knock-on impact of pausing non-emergency imaging during the peak of COVID-19 infection — a substantial increase in waiting time for CT or MRI scans[69]. In particular, the RCR[69] warned of a continuum of such figures if without more sustained investment.

Well-being

In the battle against COVID-19, the most important and valuable assets were HCPs[70]. However, a recent systematic review[71] highlighted that many HCPs faced aggravated psychological pressure and even mental illness. The intensive work drained the HCPs physically and emotionally[72]. This was especially vivid for the HCPs who had neither infectious disease expertise nor experienced the SARS outbreak[72,73]. They had to adjust to a new working environment in this extraordinarily stressful situation. Low resource countries such as Nepal, had considerable mental health symptoms among HCPs[74]. In fact, Iraqi communities who are already afflicted by the ongoing conflict, political instability and social upheavals now face an even more challenging task to secure the mental well-being of their HCPs[75].

It was reported that frontline HCPs like radiographers, who often had to take on the role of caring directly for patients with COVID-19 were at a higher-level risk of having severe mental health symptoms than those in secondary roles[76]. They had to work with the constant changing protocols with some reported to have inadvertent exposure to COVID-19 positive patients without suitable PPE — a result of poor communication[77]. Moreover, some radiographers experienced burnout as they were subjected to 12-hour shifts in order to meet the service needs and for team segregation[78]. This was in line with the systematic review which identified long working hours as a factor for increased risk of various psychological and mental illness as well as physical and emotional distress[71].

Similarly, radiologists were vulnerable to experiencing burnout with the increased emphasis on reporting speed and studies per day, long working hours, and limited personal interaction[79]. Coupled with the pre-COVID reasons for increased rates of burnout in radiology, all these stressors were being magnified exponentially during this COVID-19 pandemic[80]. As mentioned by Wolfman[80], the medical imaging profession is now facing an untenable situation where “COVID had turned a smouldering ember into a blazing fire”.

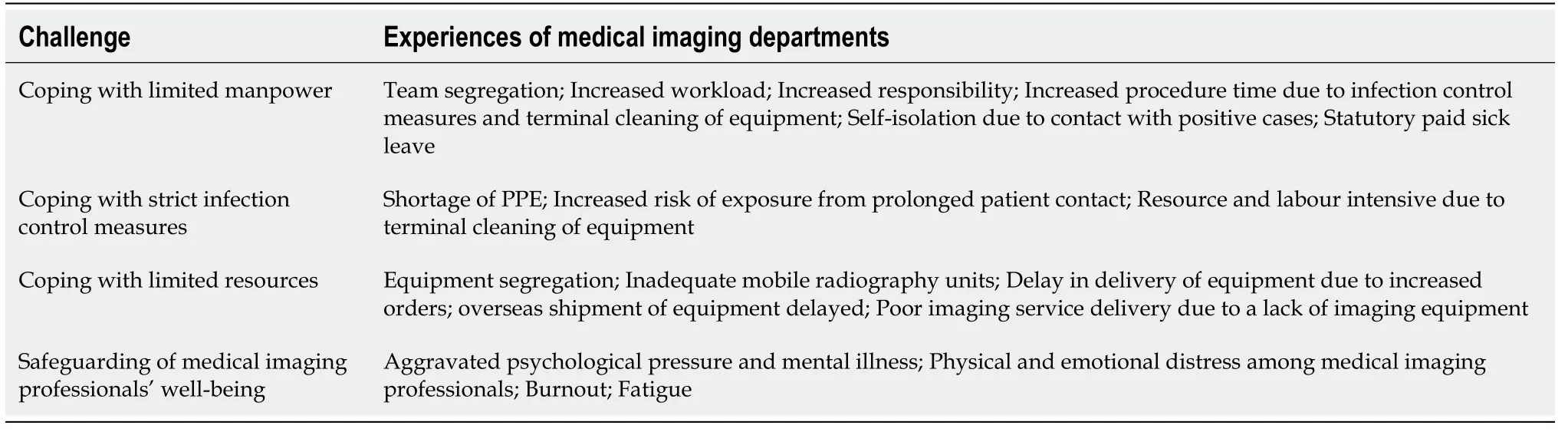

Undeniably, both radiographers and radiologists were at risk of burnout. In addition, they were also at risk of fatigue[81]. This had concerning implications as it resulted in a negative outcome in terms of patient safety in medical imaging. This could not be emphasized further with burnout and fatigue being highlighted in the joint paper[82] released by the European Society of Radiology and the European Federation of Radiographer Societies on patient safety in medical imaging. Indeed,ensuring the physical and psychological well-being of the professionals is crucial for safe delivery of medical imaging. A summary of the challenges in the provision of medical imaging service during COVID-19 is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of the challenges in the provision of medical imaging service during coronavirus disease 2019

STRATEGIES TO OPTIMIZE MEDICAL IMAGING SERVICE DELIVERY DURING COVID-19

During this pandemic, timely decisions need to be made and strategies promptly executed to mitigate the risk of widespread transmission. As the pandemic unfolds,the continuity of an effective medical imaging service for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients is essential. Notably, radiology departments must now adhere to the strictest infection control practices, different countries’ varying healthcare and lock down policies and continue to value add to patient care amidst this unprecedented challenge.

Leadership

During this period of COVID-19, strong clinical and compassionate leadership is paramount in improving the provision of quality care[83]. Similarly, Shingler-Nace[84]identified: Staying calm, communication, collaboration, coordination and providing support, as the five elements to successful leadership during this pandemic.Undeniably, this pandemic has caused a global turmoil in many aspects in our way of life and continues to challenge established leadership models[85].

Fortunately, there was a substantial amount of materials to guide radiology leaders as the profession navigates through unchartered waters[86,87]. Moreover, leadership lessons from prior pandemics were invaluable and augmented the available resources in this COVID-19 pandemic[88]. Radiology leaders demonstrated good leadership qualities in the face of adversity[89-91]. Comparably, radiographers had also shown their ability to contribute as highly effective COVID-19 leaders in safely and sustainably reorganizing radiography services[55].

There was no doubt that adaptability, flexibility, teamwork, clear communication,patient and staff safety as well as staff well-being were key principles for managing leadership teams in this pandemic[89-93]. While many would agree upon the key principles emphasized, Dr Gerada[94] highlighted in her presentation delivered at the prestigious Sir Godfrey Hounsfield Lecture, that a successful leader in the COVID-19 is one who offers hope yet bounded by realism. Clearly, one should not forget about instilling hope in times of crisis.

Use of technology

With chest radiography preferred in many countries to screen and monitor the progression of COVID-19, mobile units were in high demand. By using mobile digital radiography (DR) units instead of conventional radiography (CR) units, mobile DR solutions were a key element in turning the tide in COVID-19 management. Mobile DR units had the advantages of delivering high quality DR images in real time and had the feature of wireless data transmission which enabled early reporting and access by clinicians[55,95]. Moreover, some DR mobile units had added features to help reduce contamination, mitigating the risk of cross-infection[96]. The use of the DR mobile unit was supported and endorsed by the ACR task force on COVID-19 where it was highlighted that the surfaces of the unit could be cleaned with ease and therefore well suited for use in ambulatory care facilities[97]. In fact, recognizing the mobile DR units’ advantages, hospitals in Brazil and Namibia have since adopted a retrofit solution to their mobile CR units to meet the increasing demands[98,99].

Reducing contamination was not only a key feature in mobile DR units. CT systems were also embracing such a norm. In China where CT scans were in high demand,artificial intelligence (AI) was empowering automated patient positioning and scanning from the control console room[100]. Such an approach reduces cross infection between the radiographers and patients. Other uses of technology can be appreciated in the form of leveraging medical imaging data — remote diagnosis, data-drivenmanagement of COVID-19 operations, mounting imaging backlog and a foundation for ongoing monitoring and research on COVID-19[100,101]. Lastly, the use of AI to provide COVID-19 specific education, screening, triage and home monitoring can also help to reduce unnecessary demand on medical imaging services by supporting and providing guidance to all patients[102].

Communication

As the pandemic continues to spread globally, clear communication with radiographers is necessary to ensure infection control[103]. If radiographers are communicated promptly regarding the health of the patient to be scanned, appropriate PPE can be worn in advance — avoiding repetition of miscommunication incidents that led to radiographers in Ireland[77] being exposed to COVID-19 positive patients without donning appropriate PPE. Moreover, such clear communication is crucial in ensuring that radiographers comply and perform self-monitoring for symptoms when exposed to positive cases[101]. This can be in the form of daily routine instructions,newsletters, open forums and one-on-one communications[103,104]. Similarly, other forms of communique such as websites, virtual telecommuting and team-based communication can be utilized to ensure timely updates of current guidance and policies[105].

Clear and frequent communication amongst all members of the healthcare team has been of utmost importance throughout the pandemic[105]. This was especially crucial in the communication of imaging examination findings. In addition, rapid and prompt communication of results is also essential for staff safety and management of the patient[103]. This was highlighted by the radiology experts from Norway and Germany[106] who accentuated the role of structured reporting in communicating clear results to the rest of the team. In fact, the importance of structured reporting could not be emphasized enough with structured reporting templates that were endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the ACR and The Radiological Society of North America being made available[107]. Such reporting language and a template for chest radiography have also since surfaced[108,109].

Review of processes, protocol and policies

To prepare for any sudden patient surge and to minimize potential staff or patient exposure, many elective/non-urgent imaging procedures were postponed[110]. This was implemented with the consideration of prioritizing urgent and emergency visits while preserving PPE as the COVID-19 pandemic escalated[111]. Both the ACR[111]and RCR[112] released an advisory in the support of postponing non-urgent outpatients’ visits such as elective radiology-related procedures, cancer screenings and mammography. The postponement of breast imaging related screening was also supported by various societies[113,114]. Likewise, many non-high priority nuclear medicine procedures were also rescheduled[115]. In tandem, radiologists were tasked to review and prioritize all scheduled outpatients on the necessity of imaging at that juncture[111]. It was clear that such a decision was made deliberately with the safety of patients and staff as the utmost priority.

Patients who were scheduled for imaging procedures during this period had to be triaged before they could enter the radiology department. In Sichuan, China, a threelevel triage was introduced to categorize patients according to the different risk levels[116]. Other triaging approaches were also reported such as an external triage unit in Switzerland[117] and a pre-access telephone triage in Italy[118]. These were supported by evidence from China[119,120] which suggested that the procedure of triaging patients effectively screened patients and identified any high-risk populations. The importance of establishing a triage area was well established with the WHO regional office for Africa releasing a document[121] to provide guidance on how to rapidly establish a triage area at a healthcare facility.

As part of safe/physical distancing, radiology departments in Singapore adopted temporal and physical segregation policies to reduce the risk of cross-infection to staff and other patients and to maintain staff capabilities to meet the demand of medical imaging services[31]. For similar purposes, radiographers were segregated to different teams based on clinical location with the roster pattern fixed and synchronized with the nurses’ and radiologists’ rosters to facilitate contact tracing[55]. A similar approach was also adopted in China with success as institutions in Singapore and China reported no COVID-19 positive cases in their radiographers[55,122].

Like many hospitals globally, at the initial phase of the outbreak, many medical and radiography students were immediately withdrawn from the clinical setting or had their clinical rotations suspended for their protection[122-124]. Other work processes such as isolation mobile radiography workflow[55] and dedicated workflow management processes for modalities that required high staff numbers[125] were modified to adapt and optimize imaging services to meet the current clinical needs.Similarly, technical operations such as the undertaking of mobile radiography through side room windows[126], and the radiologist’s responsibility were also included in the review with the primary aim of optimizing the radiology protocol during the pandemic[116].

Places and equipment

The safety of HCP is paramount during a pandemic. Strict cleaning and disinfection procedures were in place to mitigate the risk of infection. Practical alternatives are needed to augment current practices especially when new waves of outbreak surface globally. This includes introduction of an imaging booth (SG SAFE.R) for chest radiography where the patient can have a chest X-ray done without contact with the radiographer—reducing the need for additional manpower while improving safety[127]. A similar booth set up (Radiology Annex) was also reported by Penn State Health which commented that such an X-ray booth offered quick scans to COVID-19 patients while eliminating the time needed to wipe down the equipment and exchange the air[128].

Radiological equipment used for scanning of COVID-19 patients should be reorganized as part of the segregation of patients to reduce the risk of cross-infection and continuum of routine radiology services[122]. Many hospitals in Singapore and China assigned dedicated equipment exclusively for suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19[4,122]. This practice was advocated by many authors and societies[58,129-131]. In addition, a dedicated transport team, low traffic access routes, lift lobbies, dedicated waiting area and scanners with negative-pressure capability were established and used[4,122,129,132]. Hospitals constrained by the availability of equipment can navigate this challenge by assigning dedicated time for COVID-19 cases[122]. Moreover, such scanning can be scheduled only towards the end of the work-day[4]. This not only reduces the risk of cross-contamination but also increases work efficiency and room utilization considering the substantial time required for cleaning the scan room[4,116]. Most importantly, terminal cleaning needs to be performed by a specialized team[4,132].

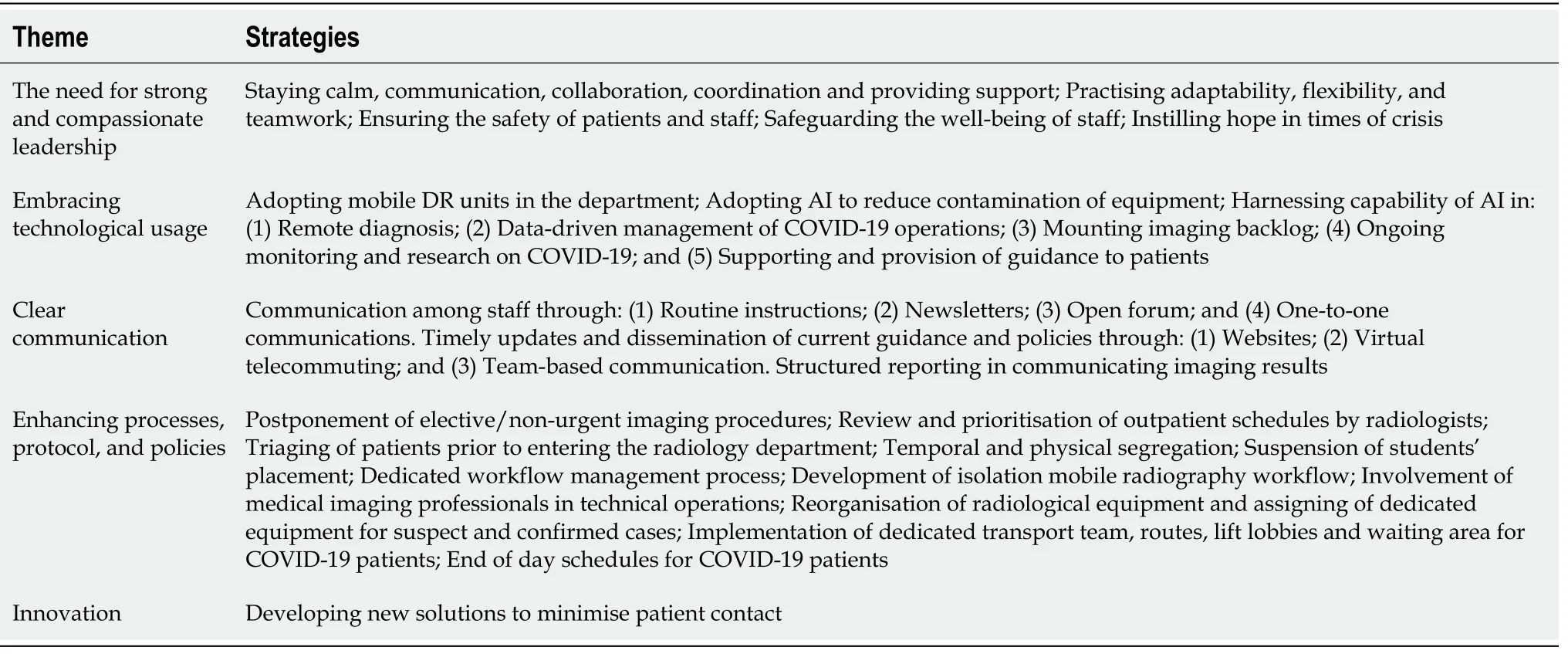

With mobile radiography and CT scans in high demand during the COVID-19 pandemic, the radiology department risks being a site of potential spread[132].Therefore, it is paramount to ensure utmost safety of radiology staff and to reduce staff and patient transmission. Mobile units require to be disinfected according to a fixed cleaning regime which might include the subsequent process of exposing the unit to ultraviolet light for more than 30 min before being used on the next patient[132,133].Other examples of protocol included having the mobile units and X-ray cassettes covered with layers of polythene sheet sealed with adhesive tapes or leucoplast[134]and wrapping of mobile DR flat detectors with disposable sheets[135]. Such protocols have since been established beyond mobile radiography and CT to include ultrasound,MRI and interventional radiology[132,136-139]. A summary of the strategies to optimize medical imaging service delivery during COVID-19 is shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Summary of the strategies to optimize medical imaging service delivery during coronavirus disease 2019

FUTURE DIRECTION

In this pandemic, there is no doubt regarding the critical role played by HCPs in the national and local responses. It is crucial to ensure that HCPs are “pandemic ready” as most of the actions required to prepare for the COVID-19 pandemic can be applied or adapted to the management of other emergencies or crises[140]. Such pandemic guidance which included recommendations were released by WHO and various public health agencies globally for more than 15 years[141]. They were likely prompted by 2 major healthcare events—H5N1 avian influenza outbreak in 2002-2005 and SARS in 2003[141]. According to WHO[140], preparedness tasks for HCPs include the development and implementation of training programmes that are based on the staff roles in an emergency, and to develop protocols to provide staff with training in an emergency and provide staff with social and psychological support. Clearly,mechanisms and systems must be in place before the pandemic to ensure that radiology staff are pandemic prepared.

To prepare HCPs for and respond to such events, it is advocated by the WHO to ensure appropriate and quality training and education are in place for all staff. Various authors have responded with remarkable vigour in sharing the approaches to prepare radiology staff for a pandemic. They included curated on-boarding programmes[142],film discussion sessions[143], use of a skill-set inventory[144], and introducing hospital arranged tutorials and video awareness campaigns[145]. It is essential to ensure that radiology staff who were battling the pandemic had the knowledge and skills needed to provide the best care for the patients while maintaining safety. In tandem, resources should be readily available to safeguard the mental health and wellbeing of radiology staff during the pandemic[144,146].

The COVID-19 pandemic had also highlighted the importance of academic institutions in raising the pandemic readiness of students. Rainford[147] identified that radiography students might not be fully confident in using PPE and suggested that practical training sessions be conducted before their placement—an approach that a Singapore academic institution adopted[123]. New norms of teaching HCPs have also been suggested by many authors ranging from virtual teaching[148,149], adoption of technology-based platforms[150,151], simulation and virtual reality[152,153].Similar to qualified HCPs, medical students who are recruited to assist in a pandemic need to undergo specific training programmes. Such student disaster training programmes improve the students’ readiness, knowledge and skills which can play a valuable role in pandemic management[154].

Compared to SARS, COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the way education is being delivered. Lessons from SARS have resulted in academic institutions establishing and increasing their online presence through effective learning management systems, video conference facilities and facilitators’ experience in elearning[155]. During this COVID-19 pandemic, many academic institutions successfully switched to online learning with just a few days of preparation[155,156].Clearly, post-SARS, there was an increased digital trajectory in the provision of education. However, this pandemic has demonstrated that online education is still not universally embraced in countries such as Argentina, Zimbabwe and Malaysia[155]. It is now incumbent upon all educators to explore online learning technology’s full potential as this pandemic can be an inflection point for further acceleration. Likewise,educators should also ensure that there is adequate training, bandwidth, and preparation for online education where it is believed to have become an integral component of school education[156].

In parallel, the preparation and practices of many radiology departments during this pandemic have been heavily influenced by the SARS experience. This has included formulation of rigorous protocols and reconfiguration of facilities to prevent in-hospital transmission, improvement of diagnostic capabilities, resourcing,communication and coordinated outbreak response[4,91,157,158]. It is undeniable that the SARS lessons have provided valuable experience for the healthcare community and was crucial in our battle against COVID-19.

Clear differences between SARS and COVID-19 have emerged. A paper published in The Lancet[159] shared the differences between both situations and the outbreak measures. Unlike SARS which was effectively eradicated by implementing top-down measures to stop all human-to human transmission, but due to the nature and extent of spread, mitigation measures must be implemented instead of containment in view of the current situation of COVID-19[159].

It was noted in a paper in Clinical Radiology[160] that the use of infection control advocated procedures might have contributed to the low staff sickness levels during COVID-19—which could be maintained after COVID-19. In addition, the need to embrace information technology was also required to develop a more robust digital platform for patients while minimizing waiting room utilization—a negative outcome of waiting room distancing and increased time for cleaning of rooms in this pandemic.Likewise, remote working and physical distancing have their pros and cons. A thorough reflection after the pandemic is required to facilitate the thought processes on practices to keep, and which to revert to pre-COVID[160]. In tandem, special attention should be paid towards building trust in the radiologist-to-clinician relationship amid the “distance” between these professionals[161]. Indeed, despite the valuable lessons from previous experiences, adaptations to practices and responses will be necessary to prepare the department for the next pandemic.

There is no doubt that effective, safe and high-quality medical imaging is paramount in healthcare. The number of global imaging procedures is increasing considerably. The role of medical imaging in medical decision-making and minimization of unnecessary interventions cannot be emphasized enough[82,162]. As highlighted by the European Society of Radiology and the European Federation of Radiographer Societies in a joint paper[82], radiographers and radiologists are essential in the provision of medical imaging services to patients, while continuously safeguarding patient care and safety. The joint paper distinctly reflects the concern of the medical imaging field where patient safety is key.

To date, a substantial amount of money and resources have been invested in AI for medical imaging[163]. There were profound concerns about medical imaging professionals being replaced or obsolete. Fortunately, they were not destined to become dodos. The American Medical Association (AMA) deliberately adopted the term augmented intelligence in place of the more common term AI and highlighted why AI could not replace medicine’s human component where it was believed that medicine could harness AI in ways that safely and effectively improved patient care[164].

As advocated by the AMA, AI is designed to enhance human intelligence and the patient-physician relationship but not to replace it[165]. Moreover, AI can help improve human effectiveness and efficiency in the form of a decision aid for clinical reasoning and decision making[166]. Similarly, for radiographers, AI can be used as a decision support tool to ensure that the examination performed is correct for a patient with dose optimization to answer the clinical question[167]. Importantly, AI will enable physicians to spend more precious time with their patients, improving the humanistic touch. Indeed, with the adoption of AI, radiologists can be freed up to perform more value-added tasks, while playing a more vital role in integrated clinical teams to improve patient care[168].

Undeniably, COVID-19 has become a catalyst for change in the development of telemedicine and AI in medical imaging services. With the global positive cases skyrocketing and many countries grappling with the sudden surge in waves of coronavirus, telemedicine must be considered and optimized. This is in line with the current guidance from the CDC for healthcare facilities[169]. Of which, the need for physical distancing has acted as a springboard for the rapid adoption of telemedicine solutions globally[170]. Through telemedicine, critical medical care can be provided to patients while reducing transmission of COVID-19 and preserving scarce resources amid the pandemic[171]. According to results of a nationally representative survey published by the AMA in 2018, radiology had the highest use of telemedicine for patient interactions although its scope has been limited[172,173]. While there is variability in the adoption of telemedicine across the world, the evidence is suggesting a positive role in this technology for developed countries in improving health systems’performance and outcomes[174]. Indeed, COVID-19 has served as a reminder about the need and future potential of telemedicine.

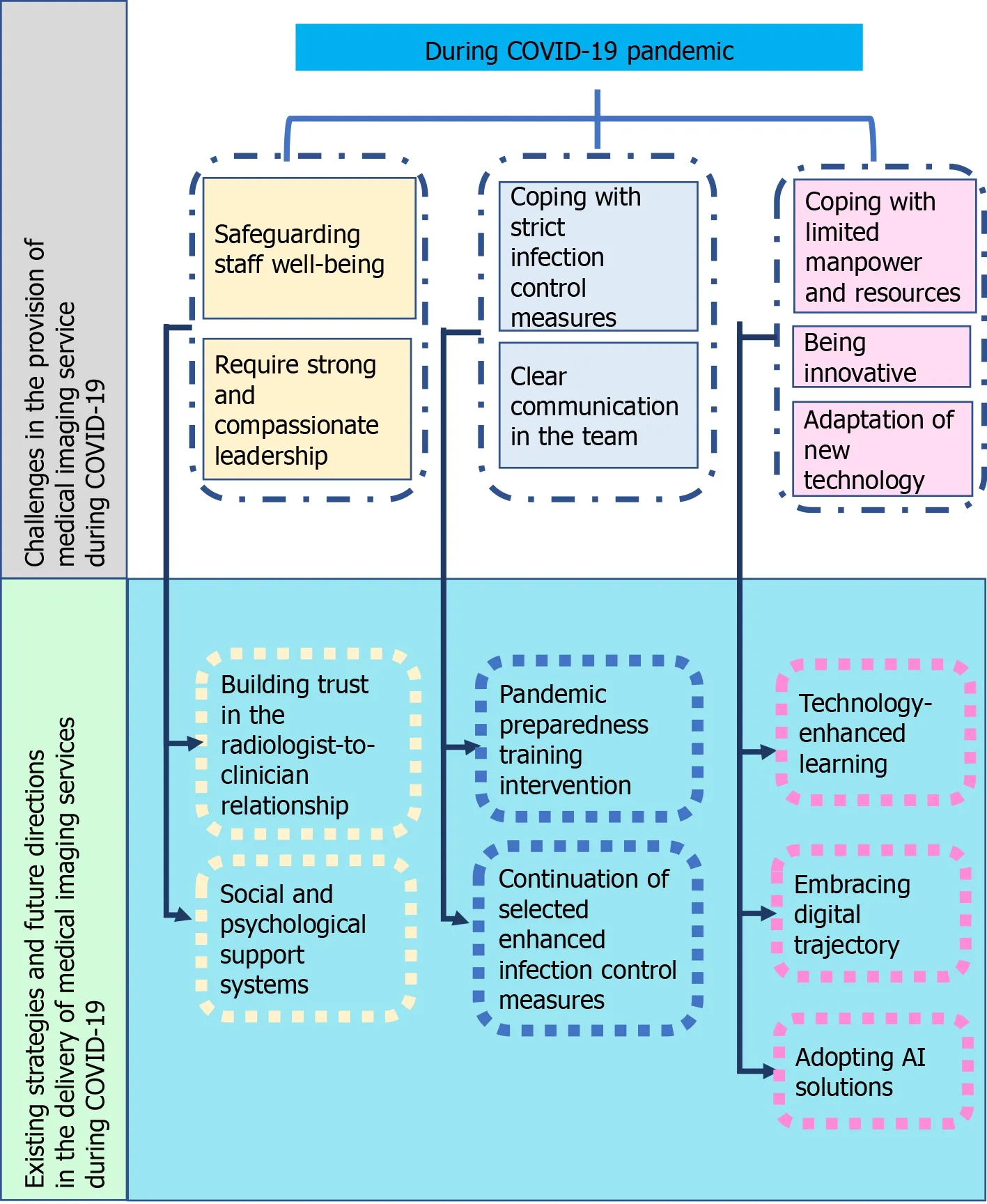

During this pandemic, AI has been harnessed in medical imaging to fight COVID-19. A collaborative network led by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering[175] has been formed to develop new tools for physicians in the early detection and optimization of treatment for COVID-19 patients. In addition, the integration of AI with medical imaging has the capability of advancing predictive medicine, preventive medicine and personalized medicine[176]. Other forms of digital transformation in medical imaging services include the use of AI in precision diagnosis, optimization of workflow and productivity[177-179]. Looking ahead, AI will be critical in empowering radiologists and radiographers across the world to address the challenges brought about by COVID-19. It is now time for medical imaging to embrace AI and the opportunities it may present in the post-COVID-19 world to enhance our patient care and patient outcome. The current challenges,strategies, and a path for future directions is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Delivery of medical imaging services: current challenges, strategies, and the path for future directions. COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; AI: Artificial intelligence.

CONCLUSION

In an unprecedented pandemic, there are significant challenges globally in delivering medical imaging services and this crisis has further highlighted how complicated these challenges can be. Amid the crisis, health care is still being delivered and with the integral role of medical imaging services in the ongoing battle against COVID-19, the quality and safety of care become more important. There are dramatic implications associated with sub-optimal radiology practices and service delivery. Implementing strategies to optimize medical imaging service delivery will ensure quality healthcare in the era of COVID-19 and beyond where patient care processes continue to change rapidly. Ultimately, through the collaborative efforts of all radiology staff, we can assure provision of high-quality and safe medical imaging services while safeguarding the health of the public, patients and HCPs.