Prospective single-blinded single-center randomized controlled trial of Prep Kit-C and Moviprep: Does underlying inflammatory bowel disease impact tolerability and efficacy?

Waled Mohsen, Astrid-Jane Williams, Gabrielle Wark, Alexandra Sechi, Jenn-Hian Koo, Wei Xuan, Milan Bassan, Watson Ng, Susan Connor

Abstract

Key Words: Bowel preparation; Inflammatory bowel disease; Tolerability; Efficacy; Moviprep; Prep Kit-C

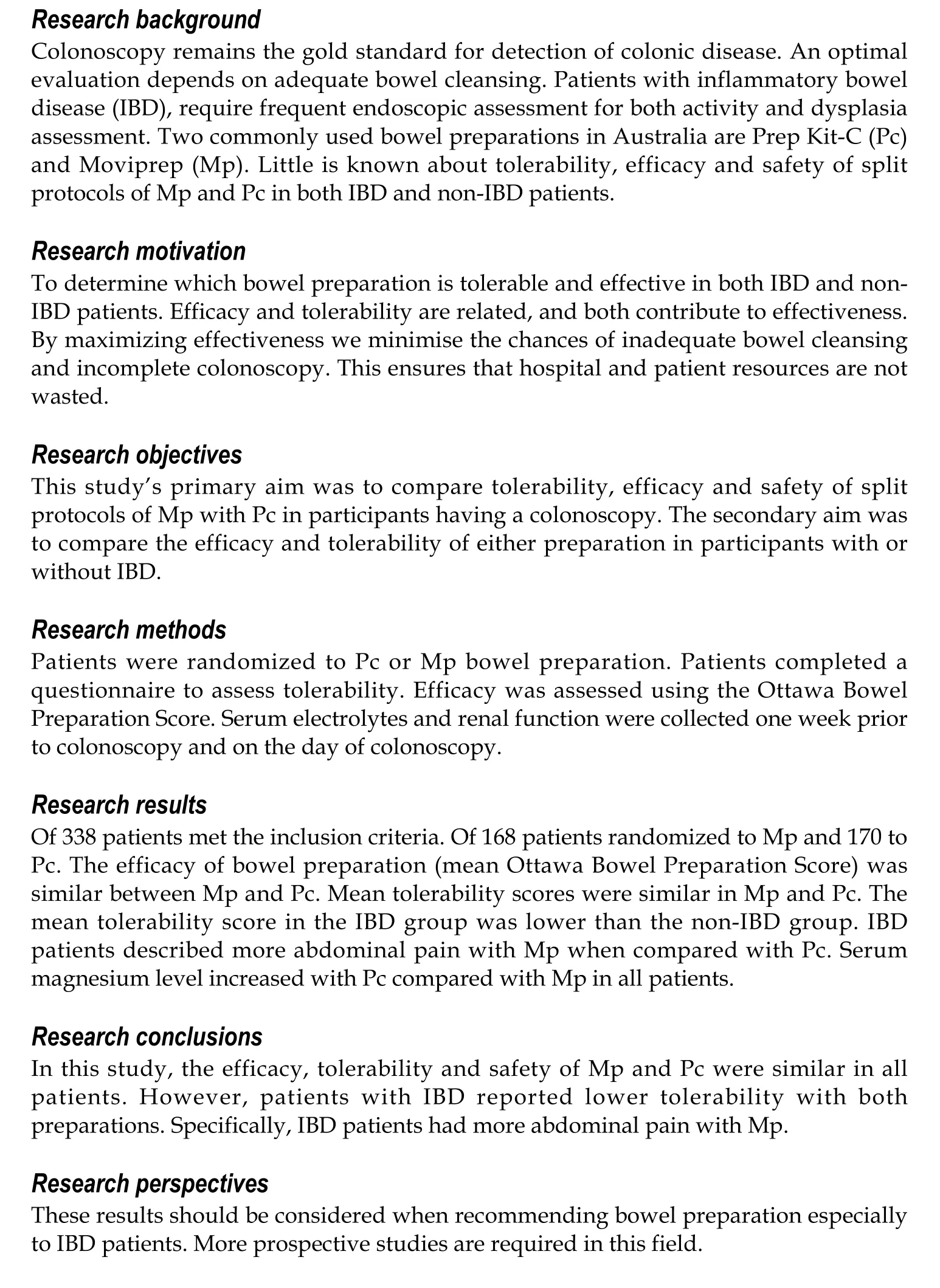

INTRODUCTION

Colonoscopy remains the gold standard for detection of colonic disease. An optimal evaluation depends on adequate bowel cleansing. Suboptimal preparation occurs in up to 25% of colonoscopies and results in aborted or incomplete examinations in up to 7% of procedures[1,2]. Suboptimal preparation is associated with longer procedural time, increased need for repeat procedures, lower overall polyp detection rates, including detection of flat (non-polypoid) lesions, small polyps (< 10 mm) and large polyps (> 10 mm)[1,3]. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends the rate of inadequate bowel preparation should not exceed 15%[4].

Efficacious bowel preparation is not solely dependent on the type of preparation used. Preparation is enhanced when instructions regarding bowel preparation are explained thoroughly, interpreters are used (when required), a split regime is used and when the type of preparation is individualized to the patient’s age and comorbidities[5,6].

Adequate bowel preparation is particularly important in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). These patients have an increased risk of developing colonic dysplasia and neoplasia. The increasingly adopted technique of chromoendoscopy is also highly dependent on excellent bowel cleansing[7]. With the increasing annual incidence (24 per 100000) and prevalence (345 per 100000) of IBD in Australia[8], efficacious colonoscopy is crucial. Low tolerability of bowel preparation is reported in IBD patients, although this has not been prospectively validated[9]. The exact mechanism driving such low tolerability is unclear. It may relate to abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting[1,9]. Additional factors that have been reported include previous surgery, intestinal stenosis, altered motility, anxiety, or heightened visceral sensitivity and pre-procedure dietary recommendations[1,9].

In the general population, poor bowel preparation is more commonly seen in males, smokers, the elderly, patients with a history of stroke, dementia, diabetes, previous colonic resection and in patients who take opioids, psychotropic drugs and calcium channel blockers[4,10-12]. Tolerability is one of the most significant factors contributing to efficacy of preparation. Efficacy and tolerability are related, and synergistically both contribute to “effectiveness” of a preparation[13]. If the preparation is not well tolerated, even if otherwise efficacious, it will not be consumed, leading to reduced effectiveness.

In Australia, several bowel cleansing agents are available. Bowel preparations are usually based on solutions of polyethylene glycol (PEG)[14,15]. Prep Kit-C (Pc) is a combination of Picoprep (Sodium picosulphate?magnesium citrate) and glycoprep (PEG). Picoprep is a small volume, hyperosmotic solution, primarily exerting its action through osmotically drawing fluid into the intestinal lumen. Moviprep (Mp) is a combination of low volume PEG solution with ascorbic acid. The ascorbic acid has osmotic laxative effects and a pleasant taste[14,16]. Both Pc and Mp are approved for use under the Australian therapeutic goods administration.

At present, there are no prospective studies which examine tolerability, efficacy and safety of Pc when compared with Mp in both the general and IBD populations. This study’s primary aim was to compare tolerability, efficacy and safety of split protocols of Mp with Pc in participants having a colonoscopy. The secondary aim was to compare the efficacy and tolerability of either preparation in participants with or without IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Methods

A prospective, randomized, single blinded trial was conducted at a single tertiary referral center. Recruitment of patients occurred from March 2013 to December 2016. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Human Ethics and Research Office (reference HREC/12/LPOOL/108).

Inclusion criteria

All patients aged between 18-75 years requiring an outpatient colonoscopy were invited to participate in this study. Patients identified as having IBD required histological evidence of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis from a previous colonoscopy.

Exclusion criteria

The following were exclusion criteria: non–English speaking, renal insufficiency (defined as an estimated Glomerular Filtration Ratio of less than 50 mL/min), cardiac failure (New York Heart Association Class greater than two), advanced liver disease (Child-Pugh B or C), poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (uninterrupted Hba1c > 8.0% for greater than one year and/or end organ complications from diabetes mellitus), bowel obstruction, total or limited colonic resection, megacolon, dysphagia and pregnancy or planning to become pregnant during the trial period. Patients with IBD who had a preceding colectomy or ileocolonic resection (that involved or extended beyond the hepatic flexure) were also excluded from this study.

Randomization

All participants were randomly allocated to a bowel preparation regime (Mp or Pc) at time of study recruitment in a 1:1 ratio. The allocation sequence was provided by the coordinating investigator. The investigator drew the patient allocated preparation out of an envelope which had equal numbers of both preparations. Patients were provided with their assigned bowel cleansing preparation at the time of randomization. The cohort was then stratified according to presence of IBD. Patients were unable to be blinded to their allocated preparation due to associated packaging and the differences in administration. Written information about the bowel preparation including appropriate diet and timing of consumption was provided and explained in detail at a clinic review prior to colonoscopy. These instructions are provided in Supplementary material 1 . All assessing endoscopists were blinded to the assigned bowel preparation.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the tolerability and efficacy of each bowel preparation in the entire cohort. The secondary endpoints were comparison of the tolerability and efficacy of the allocated bowel preparation in patients with and without IBD, as well as overall safety of bowel preparation.

Tolerability and side effects

Tolerability was assessed using a Tolerability Questionnaire modified from Lawrance et al[17](Supplementary material 2). Patients received the questionnaire at their preassessment visit and completed it after finishing their bowel preparation on the day of their colonoscopy. The questionnaire included a five-point Likert scale to assess tolerability (ranging from 0 to 5) and palatability (ranging from 0 to 5) of the preparation. A lower score indicated poorer tolerance. Common side effects (abdominal discomfort, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, dizziness and shortness of breath) were also measured on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 5). A higher score indicated worse reported side effects.

Colonoscopy

Patients were provided with written instructions and the bowel preparation explained in detail by the recruiting investigator at the time of study recruitment (full preparation instructions are available in Supplementary material 2). Apart from the preparation agent, preparation was standardized between the two groups including split dosing and 24 h of clear fluids. Colonoscopies were performed by experienced consultant colonoscopists (n = 4) or advanced gastroenterology trainees under the direct supervision of one of the colonoscopists. All procedures were performed using intravenous sedation administered by an anesthetist.

Efficacy

Efficacy of colon cleansing was assessed using the validated Ottawa Bowel Preparation Score (OBPS)[18]. All colonoscopists attended calibrating sessions prior to study commencement. Two colonoscopists were blinded to the allocated bowel preparation, independently assessed the efficacy of bowel cleansing regime during insertion of the colonoscope, prior to washing. The OBPS grades the quality of bowel preparation (0 to 4, with 0 being no fluid and 4 pertaining to fluid/fecal material unable to be cleared) in three colonic segments (right, left, recto-sigmoid) in addition to an overall fluid score. The total score out of 14 was provided for each patient and an average score calculated from both scores. A score of zero represents excellent preparation and 14 represents solid stool in each segment and excessive fluid. Inadequate bowel preparation is defined as an OBPS score equal to or greater than 8[19,20].

Safety: Electrolyte analysis

Safety of each bowel preparation included determination of electrolyte alteration. Blood was collected from each patient within one week before bowel preparation and on the day of colonoscopy prior to the procedure for serum electrolytes. Changes in serum sodium, chloride, potassium, bicarbonate, urea, creatinine, magnesium, calcium and phosphate were measured.

Statistical analyses

For the primary analysis in the entire cohort, an estimated sample size of 127 patients in each group was calculated to detect a 15% difference in the tolerability of bowel preparation between Mp and Pc, with 95% confidence and 90% power. Preliminary data using the same Tolerability Questionnaire which reported the mean tolerability of Moviprep of 13.3 (standard deviation 4.9) in patients undergoing colonoscopy was used to guide the sample size calculation[21]. The difference in tolerability of 15% between bowel preparation regimes was selected as this was also used in another study assessing tolerability of different bowel preparations[17]. Assuming a completion rate of 80%, a target of at least 159 participants for recruitment in each group was sought, giving a sample size of at least 318. The student t-test was used to compare the differences in mean scores of tolerability and efficacy. Associations between categorical variables and outcomes were assessed using Chi-square test. The IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows version 25.0 (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, United States) was used to analyze the data.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

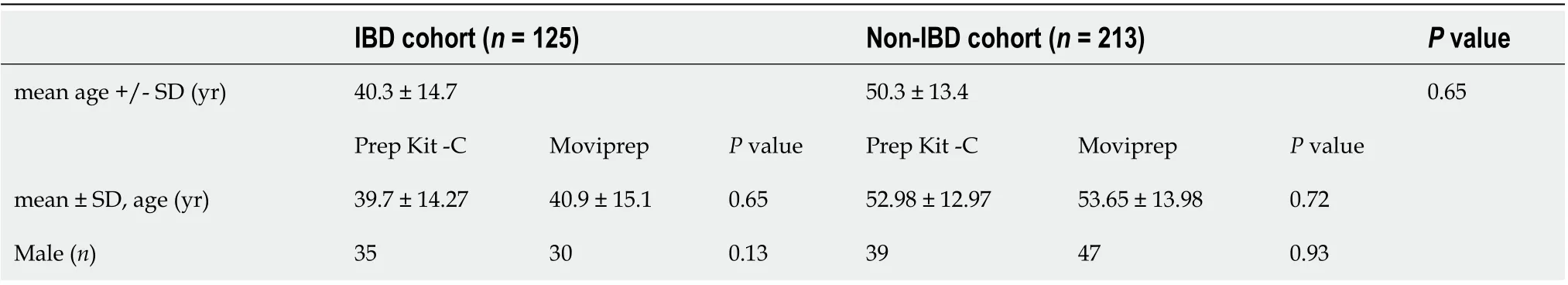

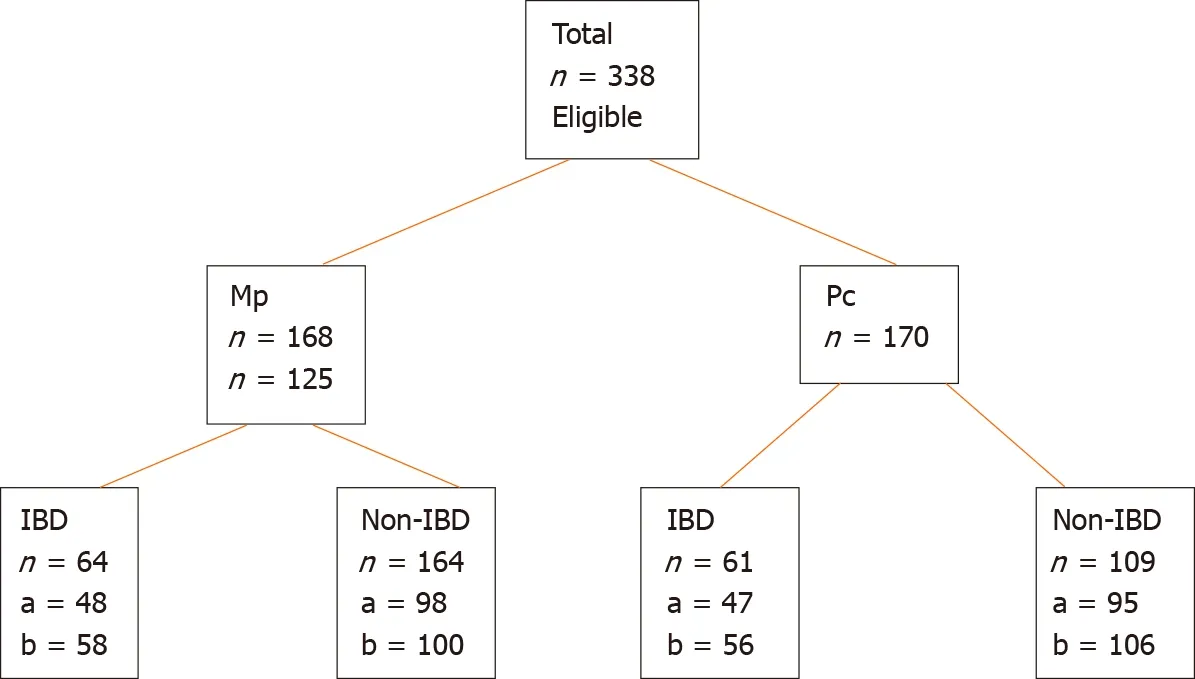

From March 2013 to December 2016, 338 patients were enrolled in the study. 168 patients were randomized to Mp and 170 to Pc (Figure 1). One hundred and twentyfive patients had a pre-existing diagnosis of IBD (58% patients with Crohn’s disease and 42% with ulcerative colitis). In the IBD group, 64 patients had Mp and 61 had Pc. In the non-IBD group, 104 patients had Mp and 109 had Pc (Figure 1). Within both the IBD and non-IBD groups, there was no difference in age or gender distribution across the allocated bowel preparation groups (Table 1). Forty percent (n = 86) of the non-IBD cohort were male, compared with 52% (n = 65) in the IBD cohort. The mean ages of the IBD and non-IBD groups were 40.3 ± 14.7 and 50.3 ± 13.4 years respectively (P = 0.65).

Tolerability and side effects

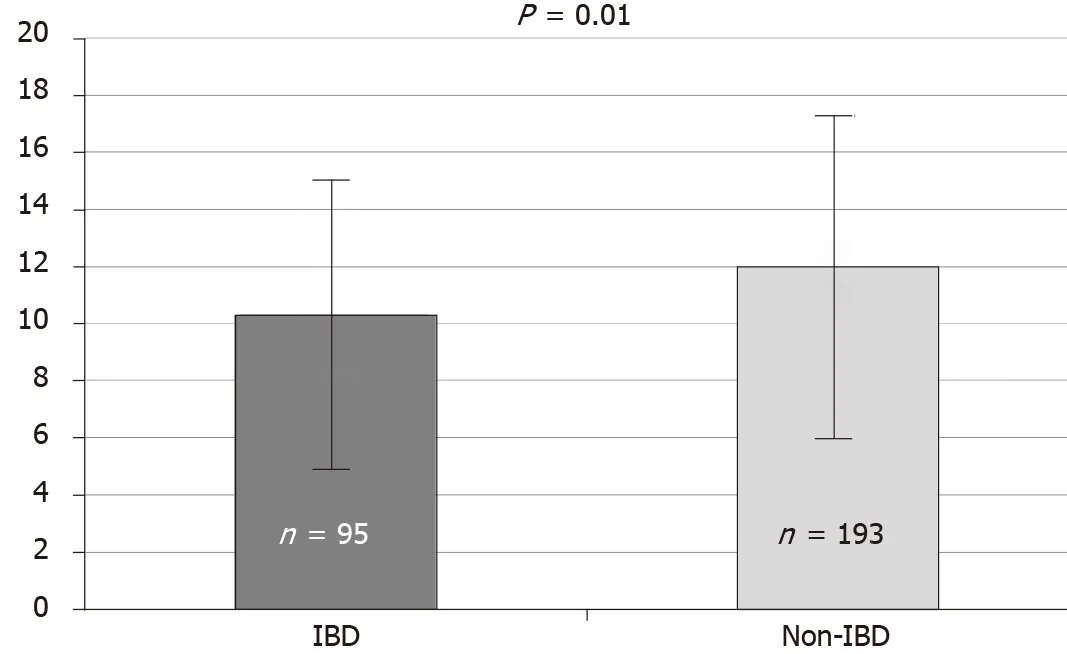

Of the 338 patients, 288 (85%) completed the questionnaire assessing tolerability (Figure 1), this proportion was similar in both the Mp and Pc groups. There were no significant differences in the mean scores for tolerability between Mp (11.84 ± 5.4) and Pc groups (10.99 ± 5.2; P = 0.17). Thirty and 20 patients from the IBD and non-IBD groups respectively did not complete the tolerability questionnaire. The tolerability score in the IBD (n = 95) group was significantly lower than the non-IBD group (n = 193) (10.3 ± 5.1 vs 12.0 ± 5.3, P = 0.01) (Figure 2), indicating poorer tolerability in this group of patients.

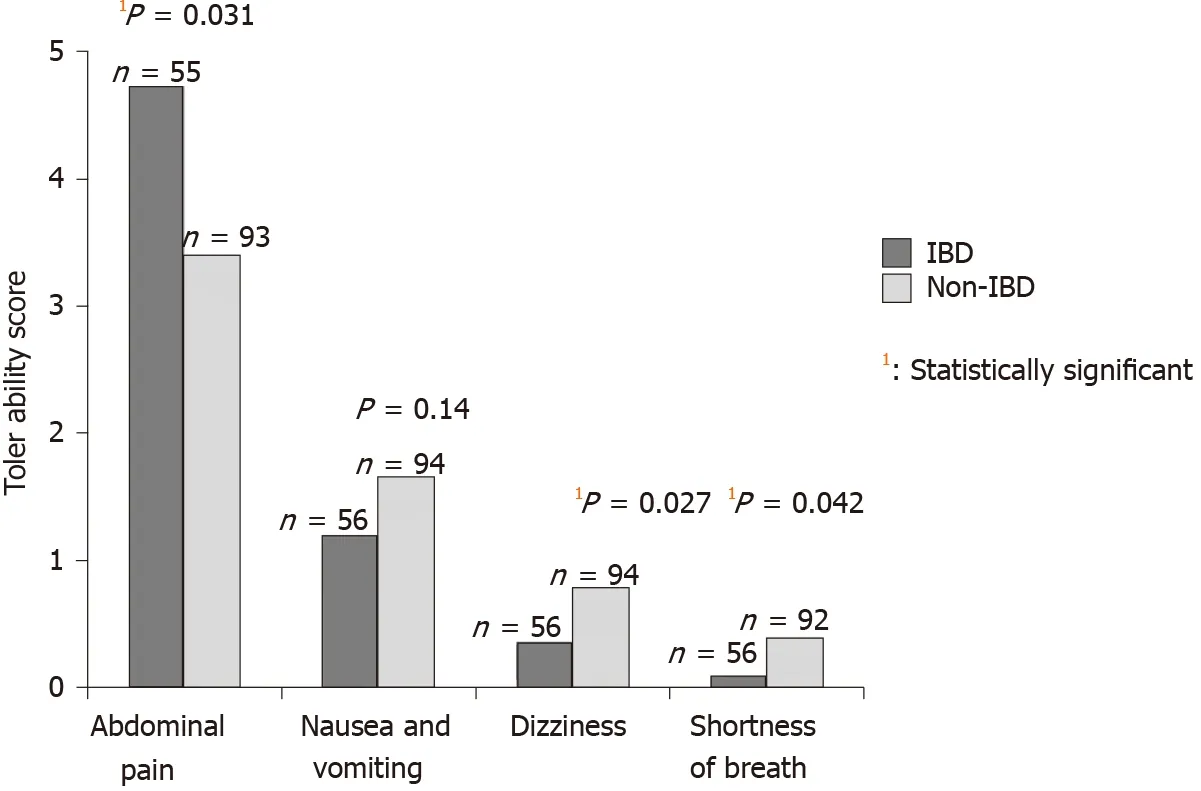

The IBD group reported higher score (indicating worse) for abdominal pain (mean 4.78 vs 3.39; P = 0.031) and lower mean score for dizziness (0.37 vs 0.78; P = 0.03), and shortness of breath (mean 0.09 vs 0.39; P = 0.042) compared with the non-IBD group. The mean scores for nausea/vomiting were similar in both groups (mean 1.15 vs 1.65; P = 0.14) (Figure 3). Within the IBD group, patients who had Mp reported more abdominal pain when compared with Pc (mean 5.7 vs 3.62; P = 0.046). There were no other significant differences in the mean scores for other symptoms within the non-IBD or IBD group.

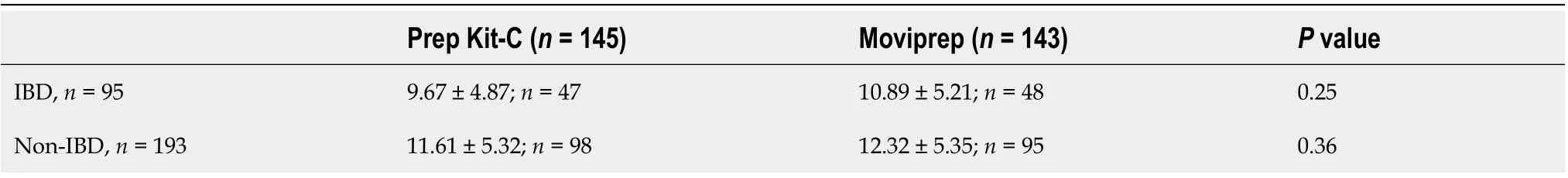

When comparing the overall tolerability of Pc (n = 145) with Mp (n = 143) in both the IBD and non-IBD groups, there was no statistically significant difference in mean tolerability scores between the two bowel preparations, although the study may not have been powered to detect a significant difference (Table 2).

Efficacy

Data on efficacy of the bowel preparation was available in 320 patients (95%). There was no difference in the efficacy within the entire group when comparing Mp to Pc [mean OBPS: Mp (n = 158; 5.4 ± 2.4) and Pc (n = 162; 5.1 ± 2.1; P = 0.73)], nor within both the IBD [mean OBPS: Mp (n = 58; 4.8 ± 2.9) and Pc (n = 56; 5.2 ± 3.3; P = 0.53)] and non-IBD [mean OBPS: Mp (n = 100; 5.5 ± 2.4) and Pc (n = 106; 5.4 ± 2.1; P = 0.84)] groups.

Efficacy of bowel preparation when comparing the IBD (n = 114) to the non-IBD (n = 206) group was not significantly different (P = 0.26). Inadequate bowel preparation (defined as an OBPS of greater than or equal to 8)[17,19]was present in 8.9% (n = 29) of all patients: 10.5% (n = 12) of the IBD group and 8% (n = 17) of the non-IBD group.

Safety: Electrolyte analysis

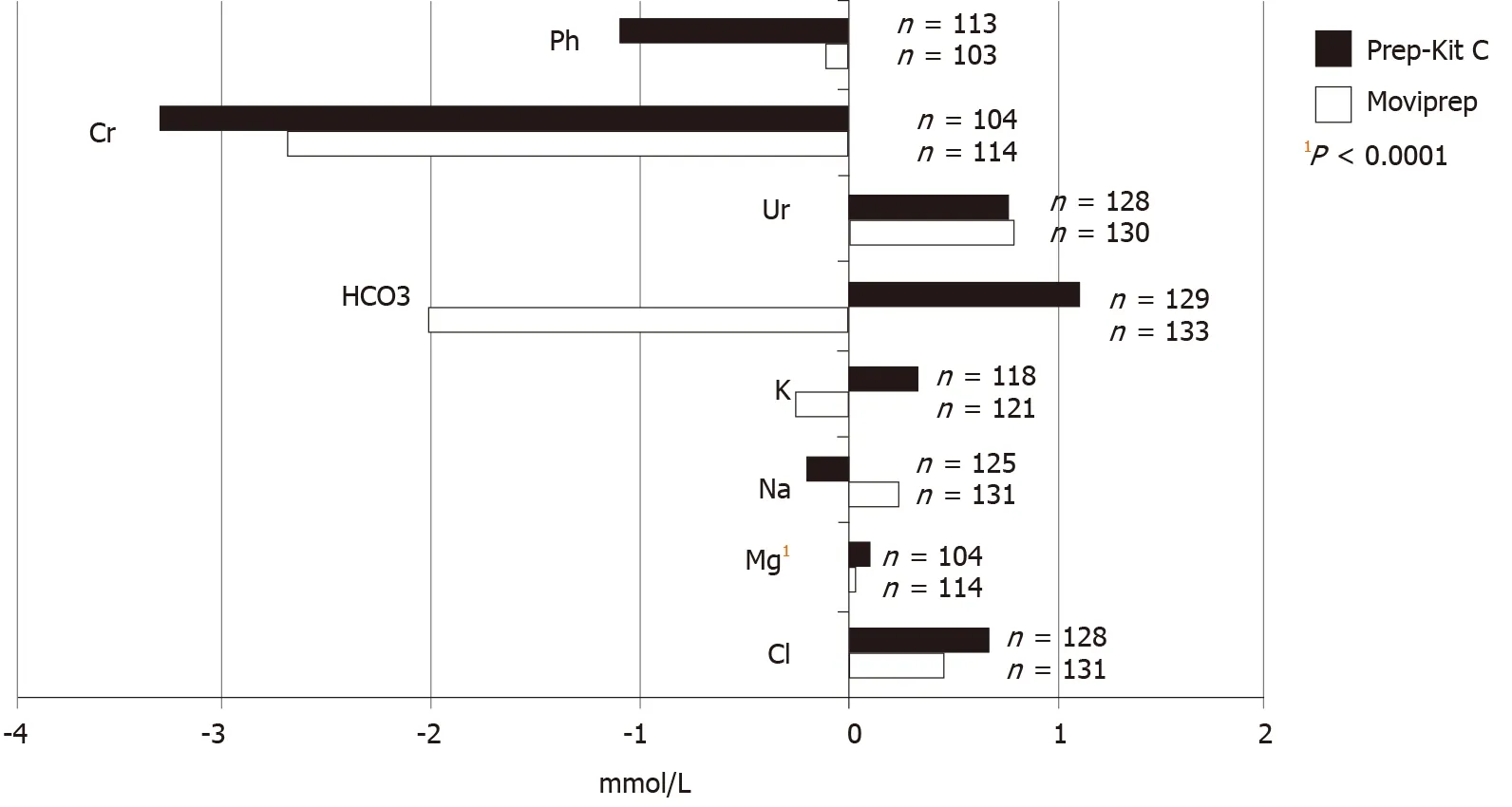

Electrolyte data was available for 256 patients (78%). There was a statistically significant increase in magnesium in patients who received Pc compared with Mp (mean increase in mmol/L: Mp 0.03 ± 0.117 and Pc 0.11 ± 0.106; P < 0.0001) (Figure 4). There were no additional differences detected in the remaining electrolytes. There were no reported clinical concerns attributed to electrolyte abnormalities during the peri-procedural period, such as arrhythmias, exacerbation of congestive cardiac failure or acute pulmonary edema.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics

Table 2 Tolerability Scores in the inflammatory bowel disease and non-inflammatory bowel disease cohorts

Figure 1 Randomization of bowel preparation. a: Number of patients who completed tolerability questionnaire; b: Number of patients with validated Ottawa Bowel Preparation Scores; Mp: Moviprep; Pc: Prep Kit-C; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease.

DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated no significant differences in the tolerability and efficacy of bowel preparation when comparing Mp with Pc. However, subgroup analysis revealed IBD patients were less tolerant of bowel preparation when compared with patients without IBD. IBD patients reported more abdomen pain with both preparations when compared with the non-IBD group. Within the IBD group, Mp produced more abdomen pain compared with Pc. Safety was comparable for IBD and non-IBD patients, although Pc resulted in a higher magnesium level than Mp.

The influence of effective bowel preparation on the quality of colonoscopy is substantial, as recently highlighted by the inclusion of bowel preparation adequacy and safety in the Australian Colonoscopy Care Standards formulated by the Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care[22]. Systematic reviews have not demonstrated superiority of any specific bowel preparation regimes when assessing efficacy in both the non-IBD population as well as in those with IBD[14,23,24]. At our center, as well as many in Australia, Mp and Pc are commonly recommended bowel preparations. Prior to this study, there have been no prospective studies which compare the efficacy of Pc with Mp in non-IBD or IBD populations. Consistent with systematic reviews for other bowel preparations, our study demonstrated no significant difference in bowel preparation efficacy between Mp and Pc in both IBD and non-IBD populations. Our findings supported both Pc and Mp as suitable choices when considering efficacy of bowel preparation regimes in patients with and without IBD[1,19,20]. Nine percent of our overall study population had inadequate bowel preparation, which falls within the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines for adequate bowel preparation in at least 85% of patients[4].

Figure 2 Total tolerability scores when comparing inflammatory bowel disease and non-inflammatory bowel disease cohorts. Of 95 inflammatory bowel disease and 193 non- inflammatory bowel disease participants included. Higher score indicates better tolerability where 0 = poorly tolerated and 5 = well tolerated. Total score is out of 20 (0-5 for taste; 0-5 ease of ingestion; 0-5 for palatability; 0-5 for amount). IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease.

Figure 3 Tolerability scores according to specified symptom. Of 56 inflammatory bowel disease and 93 non-inflammatory bowel disease participants compared. 0 = well tolerated and 5 = poorly tolerated. Maximum score for abdominal pain is 15 (0-5 points abdominal discomfort; 0-5 points for abdominal pain; 0-5 points for abdominal distension). Maximum score for nausea and vomiting is ten (0-5 points for nausea; 0-5 points for vomiting). The maximum points for dizziness or shortness of breath are 5 points. IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease.

Our study was unique in that both our IBD and non-IBD patients prospectively completed tolerability questionnaires at the time of bowel preparation ingestion. It was observed that IBD patients were less tolerant of bowel preparation when compared with patients without IBD, though the type of bowel preparation did not affect the total tolerability score when comparing IBD with the non-IBD groups. IBD patients also reported more abdominal pain when compared to non-IBD patients.

Poorer tolerability of bowel preparation within IBD cohorts is consistent with previously published literature. Denters et al[25]reported significantly more psychological and physical burden from bowel preparation in patients with IBD when compared with other patient groups. In another study, IBD patients most commonly cited difficulty with bowel preparation as the most important reason for failed compliance with scheduled colonoscopies for colorectal cancer surveillance[9]. Tolerability of bowel preparation in IBD patients may not be entirely related to luminal pathology. In another study, tolerance of bowel preparation was similar when comparing IBD and non-IBD cohorts, however co-morbid anxiety played a role in symptom development during bowel preparation in IBD patients[26].

Figure 4 Changes in electrolyte levels (n = 256) measured in mmol/L. Levels compared between one week prior to procedure and day of the procedure.

Our study provides further impetus to reinforce the importance of educating IBD patients about bowel preparation, including the possibility for reduced tolerance and more abdomen pain. IBD patient awareness about potentially poor tolerance prior to ingestion may positively impact on the bowel preparation quality and compliance with surveillance protocols. Dietary liberalization, specifically using the white or low residue diet has been shown to be better tolerated and as efficacious as a clear fluid diet[27]. Tolerability of the white diet in comparison with the clear fluid diet, prior to colonoscopy, within the IBD population is a future research area.

Our study supports the safety of both Mp and Pc. There were no reported adverse clinical outcomes. A statistically significant increase in serum magnesium level with the use of Pc when compared with Mp was identified but it was of a small magnitude and unlikely to be clinically significant. Whilst there have been no prospective studies comparing electrolyte changes or adverse outcomes in patients taking Mp compared with Pc, our study is in line with other studies which have shown that Pc can cause electrolyte derangement[24]. Thus, Pc should be avoided in the elderly and patients with renal impairment[24].

Our study has several limitations. In relation to assessment of bowel preparation tolerability, our study utilized a modified, un-validated questionnaire developed by our study team based on an existing questionnaire[17]. Whilst we acknowledge this limitation, the same questionnaire was used in all study arms (Mp and Pc; IBD and non-IBD), and the questionnaire completion rate was equivalent amongst all study arms. Furthermore, tolerability of bowel preparation may have been influenced by the volume of fluid (e.g., water) replacement consumed by each participant in addition to the actual bowel preparation. This was not standardized between groups (Supplementary material 1). The tolerability questionnaire was completed just prior to the colonoscopy. As a result, delayed tolerability side effects from the allocated preparation may have been missed. Lastly, we did not collect data about variables which may influence bowel preparation efficacy. These variables include smoking history, medication history, history of Diabetes Mellitus or disease activity in IBD.

CONCLUSION

Our prospective, randomized controlled study has compared the tolerability, efficacy and safety of Mp and Pc in non-IBD and IBD patients. We demonstrated that both Mp and Pc had similar efficacy of bowel preparation in either the non-IBD or IBD cohorts. However, IBD patients were less tolerant of bowel preparation and reported more abdomen pain compared with patients without IBD. Furthermore, IBD patients reported more abdominal pain with Mp compared with Pc. Future research opportunities in this field include assessing factors contributing to poor bowel preparation tolerability in IBD patients is required.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年11期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年11期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Eastern China

- Long-term follow-up of cumulative incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus patients without antiviral therapy

- Apolipoprotein E polymorphism influences orthotopic liver transplantation outcomes in patients with hepatitis C virus-induced liver cirrhosis

- Study on the characteristics of intestinal motility of constipation in patients with Parkinson's disease

- Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer: A multicenter retrospective study

- How to manage inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: A guide for the practicing clinician