EARLY ROMAN SYENE (1ST TO 2ND CENTURY) –A GATE TO THE RED SEA?

Stefanie Schmidt FU Berlin

Introduction

When considering the topic of ancient trade hubs in Egypt, one generally thinks of Alexandria or Koptos. Aswān, a border town in Upper Egypt, would hardly come to mind. However, medieval travellers such as the 10th century historian Mas?ūdī (895–957), described Aswān, the Roman Syene, as a central trade hub that received huge caravans laden with merchandise.1Mas?ūdī (Barbier de Meynard, Pavet de Courteille 1861–1877) III, ch. 33, 50.Although Aswān’s peak was not until Islamic times, the town was a central place of trade and production already in Roman times. Syene’s location at the First Cataract required every ship that wanted to pass the rapids to land at the town’s harbour in order to unload and transport its cargo over land before commodities could continue their travel on the Nile. Archaeological finds of Aswān pottery throughout Egypt, Nubia, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Arabian Sea make it clear that Syene not only canalized trans-regional trade, but that its economic power went also far beyond its core region. This paper aims at exploring early Roman Syene’s economic outreach especially with a view to possible connections between the town and trade carried out in the Red Sea.

The elephant in the room

To begin with a major problem, Roman Syene is only rarely mentioned as a place of transit by Graeco-Roman authors.2Other particularities seem to have been of more interest to them: Syene is frequently taken as point of reference for measuring distances between Egypt and places located in Ethiopia, cf. Plin. NH 2.75(183–184); Strabo 2.2.2, 5.7. Further points of interest were the garrison stationed near Syene, cf.Strabo 17.1.54, and the phenomenon that during the summer tropic the sun stood at such a vertical angle that it did not cast a shadow, cf. Strabo 2.2.2, 5.7; Plin. NH 2.75 (183–184); Plut. De Def. Or. 4.In fact, only a few objects of trade are itemized in literary accounts. Amongst them are the characteristic rose granite,which had been quarried at Syene since Pharaonic times,3Plin. NH 36.13 (63); Theophrast. De Lapidibus 34.and ivory, which according to Juvenal came “through the Gate (porta) of Syene.”4Iuv. Sat. 11.120–127: At nunc divitibus cenandi nulla voluptas, nil rhombus, nil damma sapit,putere videntur unguenta atque rosae, latos nisi sustinet orbis grande ebur et magno sublimis pardus hiatu dentibus ex illis quos mittit porta Syenes et Mauri celeres et Mauro obscurior Indus, et quos deposuit Nabataeo belua saltu iam nimios capitique graves. / “But these days, the rich get no pleasure from dining, the turbot and venison have no taste, the fragrances and roses seem rotten, unless the enormous round table top rests on a massive piece of ivory, a rampant snarling leopard made from tusks imported from the gate of Syene and the speedy Moors and from the Indian who is darker still,the tusks dropped by the beast in the Nabataean grove when they’ve become too large and heavy for its head.” (trans. S. M. Braund in Loeb). By “Mauri” Juvenal perhaps refers to the Troglodytes in whose territory elephants were hunted and who were known for their swiftness; see, for instance,Plin. NH 7.31; 8.26.This statement is surprising because as far as is known, at least under the Ptolemies, ivory and live elephants were shipped to Egypt through the Red Sea ports that had been established or extended especially for this reason.

Ivory was amongst the prestigious goods that had been imported to Egypt since Pharaonic times.5Ivory is among those items Harkhuf brought back from the not yet localized region of Yam: Urk. I 126.17–127.3.A rigorous exploitation of elephant hunting-grounds,however, was not initiated until the Ptolemies, who not only imported ivory, but also live elephants.6The huge amounts of ivory that reached Egypt is shown by an account of Kallixeinos of Rhodes,who reports Ptolemy II displayed 600 pieces of elephant tusk in a parade in Alexandria, cf. Athen.Deipnosoph. 5.196A; 201B. Ptolemy XII and Ptolemy XIII or XIV had still access to so much ivory as to make generous gifts to the temple of Apollo at Didyma, cf. I.Didyma (MacCabe 1985) no. 511,14–18 (54 BC); no. 318, 7–10 (Ptolemy XIII or XIV); for a discussion of the date and the donator of the latter inscription, see the edition of Wiegand 1958, no. 218 (II), p. 166 and the discussion in Burstein 1996, 804.The initial impetus for this can be found in the increasing hostilities between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid dynasties in which war elephants were deployed. While the Seleucids had access to Indian elephants, the Ptolemies had to explore remote regions along the East African coast to track them down.7Strabo 15.2.9 reports that Seleucus Nicator received 500 elephants from the Indian king. For elephant hunting under the Ptolemies, see Cobb 2016 and Burstein 1996. The latter points to a rigorous exploitation of hunting-grounds under the Ptolemies and a southward movement from initially “Ptolemais of the Hunt” on the central coast of modern Sudan to modern Eritrea under Ptolemy III and the northern coast of modern Somalia under Ptolemy IV (ibid., 801 and 806).It was probably Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC) who initiated an extensive infrastructure project aimed at importing elephants by establishing or extending Red Sea ports like Berenike.8For the existence of a prior roadstead or small harbour at the site where Berenike was founded, cf.Sidebotham 2018, 594 with n. 2.He would have also expanded the road system that Ptolemy I had constructed to reach the gold mines and added way stations between Apollonopolis Magna (modern Edfū), Nechesia (modern Marsā Nakārī?), and Berenike.9Redon 2018, 34–42; Brun 2018, 142. For a thorough survey of the desert roads between Berenike and the Nile Valley, see now Sidebotham and Gates-Foster 2019. In Ptolemaic times, transports on the sea were carried out in special large vessels called elephantēgoi which needed spacious harbours like Berenike; cf. Sidebotham 2011, 46 and 48–52; W.Chr. 452, 22. 26 (224 BC, unknown).

Three major roads connected the Red Sea and the Nile under the first three Ptolemies: the Myos Hormos-Koptos route, the one from Nechesia to Apollonopolis Magna, and that from Berenike to Apollonopolis Magna.10Redon 2018. The major Ptolemaic-Roman roads and their way stations are listed in Sidebotham,2011, 129–135, tab. 8-1. For the course of the routes, cf. also Graeff 2005, 163–168 (Koptos-Berenike);173–175 (Apollonopolis Magna-Berenike). However, he missed the significance of the latter route for the elephant transports.Until the time of the Great Revolt in the Thebais at the end of the 3rd / the beginning of the 2nd century BC (205–186 BC), elephants and probably ivory were transported via the route from Berenike to Apollonopolis Magna.11Way stations, like fort Bi?r Samūt, and traveller inscriptions that report on activities in the Red Sea and elephant hunting give ample evidence of active traffic on the way between Apollonopolis and Berenike; cf. Bernand 1972a, no. 9bis; pl. 54; 1977, no. 77; Mairs 2013.Thereafter,the major route shifted to the better controllable northern route towards Koptos,probably because of the fraught security situation in the Thebais.12Redon 2018, 37–38. The Great Revolt in the Thebais is discussed by Ve?sse 2004.Around that time, probably under Ptolemy IV Philopator (221–205 BC) or under Ptolemy VI Philometor (180–14Periplus Maris Erythraei (ed. Casson 1989) 3.5 BC), imports of elephants stopped.13Sidebotham 2011, 53.This may not have had an effect on the import of ivory, but it remains unclear whether tusk continued to be imported from the same places as before since the author of the 1st centuryPeriplus Maris Erythraeistates that at his time ivory was available at Ptolemais Theron – the former major trade hub – only in small quantities.14It may thus be that by the time of Juvenal, the Romans had discovered other sources and import routes for ivory – possibly via Syene and Elephantine.

Syene, but more so Elephantine with its telling name, have been related to ivory trade since Pharaonic times,15Whether or not the “Elephantine / Ivory Road” (w?.t ?bw) that connected Elephantine / Syene by way of the Dungul and Kurkur oases with the Darb al-Arba?īn got its name due to a leading position in the ivory trade is discussed controversially in research; cf. Graeff 2005, 114; Goedicke 1981, 3.although written sources testifying to this are scanty. The only alleged reference to ivory in ostraca from Syene / Elephantine was rejected in the recent past: Several texts mentioning the Demotic taxn?tled Sten W?ngstedt to assume that under Ptolemy II people in Syene / Elephantine paid a tax on ivory (from Hieroglyphicn??.t“ivory”).16W?ngstedt 1968, 29–34. Burstein 1996, 804 followed W?ngstedt in this interpretation.W?ngstedt’s interpretation was doubted by several scholars and corrected by Brian Muhs, who suggested it may be a defective spelling of the more frequent yoke taxn?b.17Muhs 2005, 35–36 with further literature. I thank Andreas Winkler for this reference.However, there is indeed some evidence, if only meagre, for elephants / ivory in the region of the First Cataract. A reference to elephants appears, albeit indirectly, in two Ptolemaic inscriptions from Abū Simbel. The graffiti refer to anelephantothēras, an elephant hunter, and an “Indos” which the editors identified as a trainer or driver of elephants.18Bernand and Masson 1957, nos. 14, 20, 27, and p. 40. See a similar inscription from el-Kana?s that mentions a Sophōn, Indos (Bernand 1972a, no. 38), and the discussion in Mairs 2013, 174–177.For elephant hunting in the area of Abū Simbel, cf. Desanges 1970. There may be a further piece of evidence for elephants in this region: The Museum of Cairo hosts two statues of bronze elephants linked by a chain. Desanges 1970, 35 reports that they were acquired by the museum on 30th of May 1908 probably from excavations in Areika, Korosko (inv. 40 157 and 40 158). However, he admits that information about the provenience could not be verified.In Philae and Syene, elephants played a role in dedications and monumental buildings, for instance, in a Ptolemaic inscription from Philae dedicated to Isis, Sarapis, Harpokrates, and Ammon, thetheoi sōtēres, who were asked to ensure the safety (sōtēria) of the elephants.19Bernand 1989, no. 309; SEG XXXI 1528. Nachtergael 1982, 179 assumed a dedication for good hunting in Ethiopia and dated it to the second half of the 3rd century BC, followed by Jaritz 1998, 466, n.39. Bernand 1989, 283–284, comm. l. 3 argued the dedication aimed at a good return of the remaining war elephants from the battle of Raphia in 217 BC. Already Roccati 1981, 326–327, no. 6, linked the inscription tentatively to the battle of Raphia, but remained cautious. Pol. 5.86 reports about the battle that 16 elephants died and almost all the others had been captured by the enemy, while the Raphiadecree (Dem.) on the other hand mentions that Ptolemy captured all elephants of Antiochos III, cf. Hu? 2001, 399, n. 139, who cites Thissen 1966, l. 14. Whether the inscription was set up for a secure return of a possible remainder of Ptolemaic war elephants, or if it was dedicated in favour of a good hunt to replace those killed in the battle can certainly not be decided. But the choice of Philae as place of the dedication may indeed support a connection with Raphia since the help of the divine couple Sarapis-Isis was seen as reason for the positive outcome of the war for Ptolemy IV Philopator (221–205 BC);cf. Bricault 1999, 337–340. Dedications for a good hunt, on the other hand, could also have been made at other places in Upper Egypt. A similar inscription from Apollonopolis Magna, for instance,the major hub for the shipping of elephants at that time, was dedicated to Ptolemy IV, Arsinoe III,Sarapis, and Isis, and clearly referred to a hunt (epi tēn thēran tōn elephantōn); cf. Bernand 1977,no. 77 (222/221–205/204 BC).In Syene, a statue of an elephant (133 x 73 cm) made of Aswān rose granite was discovered south of the Temple of Isis.20Jaritz 1998, and ibid., 463 for the measurements.As further excavations in area 15 showed, it may have stood on a pedestal that was part of a monumental building with further pedestals of this kind. Wolfgang Müller, the lead excavator in Aswān, considered it possible that the monument was dedicated on the occasion of the third or fourth Syrian War and could thus have depicted elephants that had been captured either under Ptolemy III or Ptolemy IV.21I thank W. Müller for this information (by Email, 23rd of April 2020). See, moreover, Müller 2013,127–129. Jaritz 1998, 461 surmised on basis of its physical appearance that the elephant was either from Asia or India. However, as Casson 1989, 108 pointed out, in antiquity the African elephant was believed to be smaller than the Indian. This is also exemplified by Polybius’ account of the Battle of Raphia (Pol. 5.84.6) in which he surmised that Ptolemy’s elephants were afraid of the Indian elephants due to their strength. Thus, the statue in Syene may have been either an Asian/Indian or African elephant.The precise workmanship of this statue and a similar one found in Alexandria22A second statue, which almost exactly resembles that from Syene (130 x 72 cm), was found in Alexandria and is now part of the collection of the Museum of Art History in Vienna; cf. Keimer 1952–1953; Komorzynski 1952–1953, 266–268; id. 1954–1956. Jaritz 1998, 463 surmised that both statues were probably made in the same workshop in Syene.suggests that people in Syene at least knew what elephants looked like.23This is also reflected by a rock drawing of an elephant in Wadī (Chor) Abū Subeira, ca. 15 km north of Aswān; cf. Mayer 1981.However, this is not yet proof enough to state whether the living animals passed through the town.

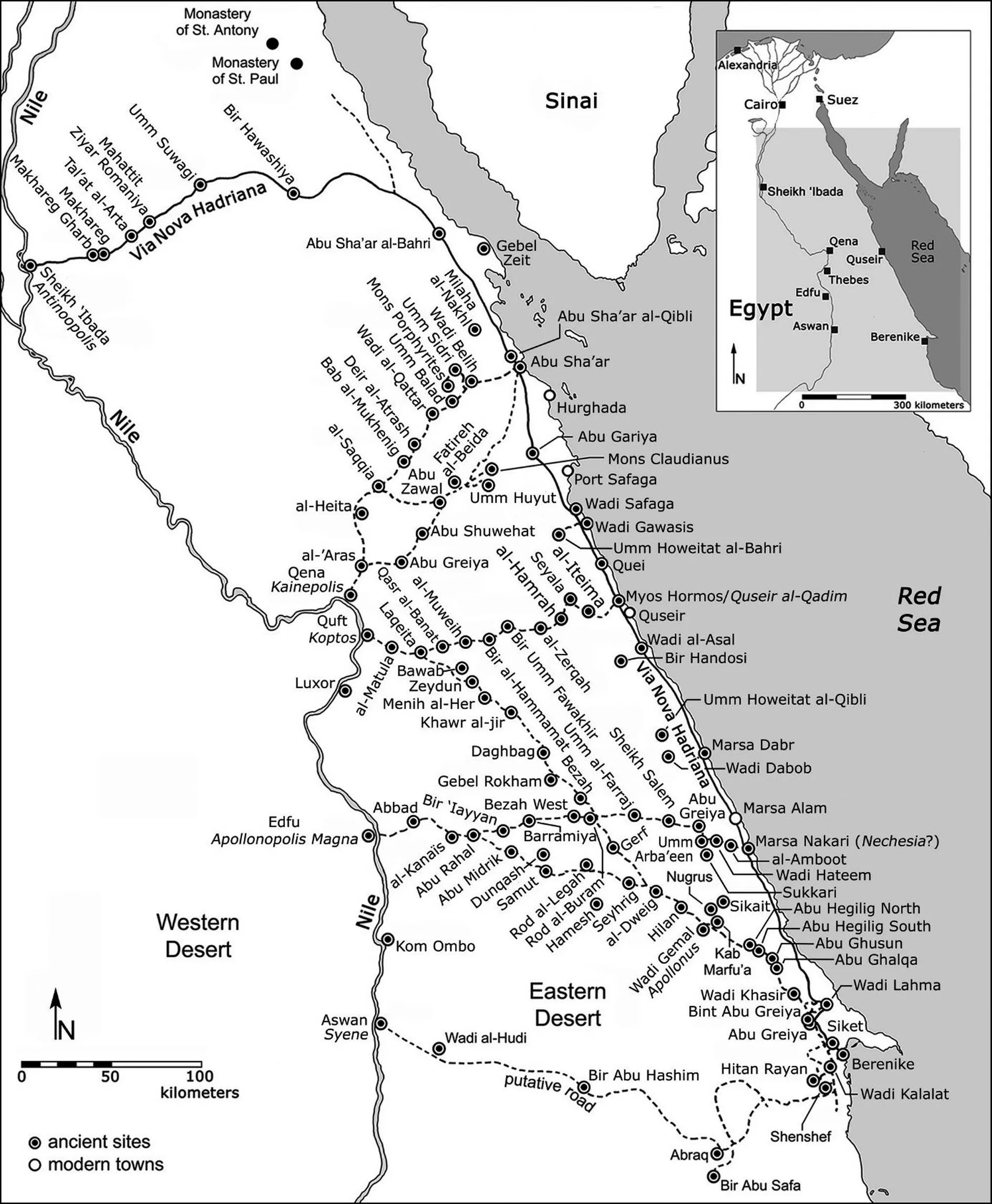

While the epigraphic and papyrological evidence is ambiguous about the presence of ivory and / or elephants in Syene, recent zooarchaeological studies show that tusks must have reached the town. Findings in Syene consisted primarily of chips and small pieces of ivory, but they showed evidence of workmanship.24Sigl 2017, vol. 1, 187–188 and vol. 2, 2.4.9, pp. 391–392, tabs. II.2.107–110. See also Rodziewicz 2005, 31–32 and pl. 105.2 who compared the techniques of bone carvers from Syene with those known from early Roman Alexandria.The findings, dating from late Pharaonic, Ptolemaic, and Roman times, were mainly gathered in three areas in Syene (1, 13, 15)25Sigl 2017, vol. 1, 188; vol. 2, 2.4.9, pp. 391–392, tabs. II.2.107–108.which nurtures suspicions that we are dealing with workshops for the production of ivory objects in the town.26Ibid., vol. 1, 188 pointed out that this concentration may have several reasons, among other things a pre-selection by the excavators or the loss of collected objects. However, the latter argument would only extend the picture and thus allow for considering a wider distribution of workshops in the town.However, archaeologists have not yet been able to assess whether the tusks came from the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) or the hippopotamus.27Ibid., vol. 1, 187 with n. 656; 294.If it came from the latter, it would give Juvenal’s satirical note a slightly different turn (if he had known it).28Juvenal is said to have been exiled in Egypt under the pretext of commanding a cohors; for a discussion, see Highet 1937. Malalas Chron. 10.49 reports he was sent to Pentapolis, to the extreme west of Egypt. The scholia, on the other hand, which are contained in the Pithoeanus manuscript(Wessner 1931), inform us that he was sent to Hos or Hoasa, the Great Oases. It adds, moreover,that he was sent “ad civitatem ultimam Aegypti,” see P scholia 1.1; 4.37; 15.27; and Highet 1937,498. Juvenal’s detailed knowledge of Egyptian geographic and cultural peculiarities, like the dispute between the towns Tentura (Dendura) and Ombi (Negadeh) described in Satire XV, gave reason to believe that he spent some time in Upper Egypt. However, his commentary “quantum ipse notavi” (Sat.15.45) must not necessarily indicate that his report is based on personal observation, as commentaries to the edition already noted (e.g., Adamietz 1993, 440, n. 17). The assumption that Juvenal’s place of exile was the garrison town of Syene is nowhere testified and only based on the information that he commanded a cohort as described in the biography attached to the Pithoeanus manuscript; for this, see Highet 1937, 499. Whether Juvenal’s detailed knowledge of some parts of Upper Egypt also included the actual sources of ivory cannot be determined with any degree of certainty at the moment.Ivory from the hippopotamus was less expensive since the animal had its habitat north of the First Cataract until modern times, and as a domestic commodity it was not subject to import taxes.29Sigl 2017, vol. 1, 187 for the habitat of the hippopotamus until modern times.If it came from the elephant on the other hand, it had to be imported – either by travelling directly across the southern border via the Meroitic kingdom30For instance, along the so called Elephantine / Ivory Road that connected Elephantine / Syene by way of the Dungul and Kurkur oases with the Darb al-Arba?īn; cf. Graeff 2005, 113–117; Goedicke 1981.or from the Red Sea, maybe via an as yet undiscovered route through the Eastern desert. This latter route may indeed have existed. Surveys carried out by Steven Sidebotham and his team suggested that there was at least one major route that connected Berenike and Syene (fig. 1). It passes the Ptolemaic-Roman hilltop fort of el-Abraq to the west of Berenike31The road turns to the West below Shenshef; cf. Sidebotham 2011, 67, figs. 5–6.and Bi?r Abū Hāshim before it leads to the Wādī el-Hūdī, a site of amethyst and gold mining 35 km southeast of Aswān.32Ibid., 128. For the eastward road from Syene, cf, Graeff 2005, 177–178. For the mining site, cf.Klemm and Klemm 2013, 288–293; Shaw 2007; Shaw and Jameson 1993 and the inscriptions from Wādī el-Hūdī in Fakhry 1952. No. 14 indicates that Wādī el-Hūdī belonged to the first nome in pharaonic times. I thank Lukas Bohnenk?mper for his help in understanding the Hieroglyphic text.In awādīclose to el-Abraq two rock drawings of an elephant were found. However,the current state of investigation cannot specifically determine whether this means that the transport of elephants was organised along this route.33Sidebotham 2011, 41; Sidebotham, Hense, and Nouwens 2008, 163, fig. 7.11.

Thus far, there is no further evidence of ivory coming through the Gate of Syene, and as for the ivory found in the town it is not possible to say where it came from without further analysis of the tusks.34There is another ivory object that was found in a tomb in Syene in area 6 dated from the early 7th century: a small plate (KF7: width: 7 cm, thickness: 0.4 cm), probably part of an originally square plate that was glued to a wooden box, perhaps a reliquary, cf. Fünfschilling 2017, 357–359. However,whether this was manufactured in Syene remains unclear.However, the question of which way goods travelled in order to reach Syene does not exhaust itself in the evidence or absence of ivory. Ivory is just one of the few items mentioned by the ancient literary sources in connection with the Roman town.

Recent studies by Johanna Sigl show that a broad variety of molluscs and fish were found in Syene whose natural habitation was not the Nile, but the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean; amongst them are the remains of a Longnose parrotfish from a coral reef on the Red Sea coast.35Sigl 2017, vol. 1, 219, 239–240, and 247–269. The following list based on Sigl’s catalogue contains only species with a Red Sea / Indian Ocean background that can, moreover, be dated to the Roman period: Longnose parrotfish (ibid., 239), tridacna maxima and squamosa (ibid., 254),venus clams (ibid., 256), vetigastropoda (turbo sp.) (ibid., 256–257), neritidae (ibid., 257), tricornis tricornis (ibid., 260), cypraeidae, in particular cypraea tigris and mauritia grayana (ibid., 260; 262–263), tonna dolium (ibid., 263; 265), charonia (ibid., 265), euplica varians (ibid., 265), oliva bulbosa(ibid., 266), cone shells (conus sp.) (ibid., 267), and dentaliida (dentalium cf. reevei) (ibid., 269).Moreover, architectonica perspectiva (ibid., 267), but probably from the Ptolemaic period (2nd to 1st cent. BC) (ibid., 267) and a shark bone (selachii) (ibid., 219), but this could also have come from the Mediterranean Sea.These may have been brought along by travellers or craftspeople, for instance, those working in the quarries of the Eastern Desert,36Ostraca that can be dated to the reign of Trajan refer to Syenites in the quarries at Mons Claudianus; cf. Cuvigny 2014b, 344. Their experience in mining and stone working was certainly a reason for employing them in several other quarries as can additionally be exemplified by a Syenite smith working in Wādī ?ammāmāt; cf. Bernand 1972b, 91.the military (a soldier of thecohors II Ituraeorum equitatais found operating in Berenike in September 61 – thecohors II Ituraeorumwas stationed in Syene, probably until the reign of Trajan)37O.Berenike II 126, 3 and line commentary (61, Berenike) and O.Berenike III, pp. 17–19. For the unit’s deployment in Syene, see also Maxfield 2000, 411.or commuting merchants.Fish could be transported long distances over land if dried or pickled. Remains of such prepared fish were found, for instance, in way stations and mines in the Eastern Desert.38Sigl 2017, vol. 1, 239.Fish may therefore have been imported as food for the journey. Mussels and snails on the contrary would probably not have stayed alive during a journey from the Red Sea to Syene. The most plausible explanation for the presence of these molluscs in Syene is thus, as Sigl surmised, that they were not primarily imported for consumption, but as curiosities or to make jewellery out of the shells.39Ibid., 240, 247–248, and 292. For beads and pendants coming from the Red Sea ports and found in Meroitic and Post-Meroitic Nubia, cf., for instance, the studies of Then-Ob?uska (2016 and 2019).The findings indicate that there was at least some kind of connection between Syene and the Red Sea / Indian Ocean, probably by travellers commuting between the ports and the First Cataract.

The dimension of these networks can best be demonstrated by the distribution of Aswān pottery. Although it was not necessarily an object of trade itself(amphorae, for instance), finds throughout Egypt and beyond its borders reflect the vast extent of early Roman Syene’s economic outreach. Aswān pottery was found, for instance, in the Eastern Desert, in Nubia, and along major maritime trade roots to India. In Roman Koptos, the table vessels of inhabitants (area A and B) were to a large extent manufactured in Syene pottery workshops.40Herbert and Berlin 2003, 29–30 and 101–121 passim, for instance, R2.1, p. 110 and R3.2–5,p. 116.Examples of Aswān fine ceramics such as a painted cup called the “coupe au danseur” were found in Gebelein.41Ballet 1998, 46; fig. 19; Jacquet-Gordon 1985, fig. 1, 3; p. 412, no. 4; pl. II, 3; Ballet 1996, 834,fig. 6 with p. 830 (origin Gebelein).Among the earliest Roman examples of Aswān pottery in Nubia is theamphoraGempeler K 703 of the Aswān Clay Group I (1st–3rd cent.) of which a similar form was discovered in Aksha (1st /2nd cent.) and in the necropolis of Faras (2nd / 3rd cent.).42Gempeler 1992, 189. For Aswān pottery in Nubia, see generally Adams 1986.Aswān pottery was also exported beyond the navigable waters of the Nile. 57 Aswānamphorae(1.5 percent of total) were found in thepraesidiumDidymoi in the Eastern Desert.43Brun 2007, 507; 509–510, fig. 7; 513; 522–523. Aswān pottery was found in contexts between 76/77 and the beginning of the reign of Marc Aurel. After this period imports of Aswān amphorae seem to have ceased and been replaced by smaller vessels.In thepraesidiumMaximianon (al-Zarqā), vessels corresponding to the ceramic products from the region of Aswān represented ca. 13 percent of all ceramic dishes.44Brun 1994, 14. Findings consisted, moreover, of four Aswān amphorae; cf. id. 2007, 519.Findings in the quarries of the Eastern Desert included not onlyamphorae, but also a large variety of functional types of Aswān pottery.45For pottery from the surveys in the Eastern Desert carried out between 1987–2015 by the University of Michigan and the University of Delaware, cf. now Gates-Foster 2019, esp. at 295; 296,tab. 4.4; 321; 340; 342 and Tomber 2019, esp. at 380 and 382 for pottery from Kab Marfu?a.Given the fact that the quarries were also worked by Syenites, who may have brought their cookware along with them, the existence of Aswān utility vessels in quarries is probably not surprising.46See above, n. 36.In Wādī ?ammāmāt, for instance, Aswān bowls that probably date from the 1st century were found in the dwellings of the workers.47Ballet 2018, 557.At Mons Claudianus, assemblages included Aswān fine wares, cooking and table wares as well asamphorae.48Tomber 1992, 138–139. Aswān red-slipped wares date probably from the 2nd century and occur in form of bowls, dishes, and beakers / cups, cf. ibid., 141 and ead. 2018, 568, where she dates the Aswān thin-walled wares with barbotine decoration to the Trajanic period and those with painted decoration to late Hadrian’s reign.It should also be mentioned that a good part of inscribed pottery sherds (ostraca) consisted of re-used Aswānamphorae, such as,for instance, those from Krokodilo.49Caputo 2019, 104. This can also be observed for later times, since, for instance, some of the ostraca the hermit Franke wrote upon had been made from Aswān clay, cf., for instance, O.Frangé 15; 25;26; 36.Aswān pottery was found in Late Roman contexts at Mons Porphyrites, specifically in the workers’ village, the necropolis,the quarry village, Lepsius’ huts, and the Blacksmith hut. It included Aswān beakers, bowls, casseroles, jugs, flagons, and anamphora.50Tomber 2001, 254; 256; 259; 262; 264–266; 268–270; 273–274; 276–277; 279–280; 282; 286–287;291; 293–296; 298; 300; 302.Fine wares made of Aswān pink clay were found in Berenike,51Dzwonek 2017.but were also brought on ships that set sail for India. At theemporionKanē (Bi?r ?Alī), for instance, an important port of trade for frankincense,52Seland 2010, 26–28.Aswān fine wares were identified.53Ballet 1998, 49, fig. 22; Ballet 1996, 826 and fig. 26.Some Aswān pottery, roughly dated to the first three centuries of the Roman era, was also found at Moscha Limēn (perhaps Khor Rori in modern Oman),54For the town, cf. Seland 2010, 29–31.amongst them,jugs, jug handles, and some bases of vessels.55Tomber 2017, 344–347.The small number of finds led Roberta Tomber to surmise that the pottery was part of the on-board provisions of Egyptian sailors to or from India.56Id. 2012, 208. Moscha Limēn was probably not on the route to India but is said to have also received ships from Kanē; cf. Periplus Maris Erythraei (= Casson 1989) 32.

The distribution of Aswān pottery, even if it was not always the object of trade itself, thus provides clear evidence of direct and indirect contact between Syenite manufacturers, the Eastern Desert, the Red Sea harbours, and actors in the Indian Ocean trade. A further means to illustrate trade connections is found in the administration and taxation of trade. In the following I will thus try to identify some actors in the organization of the Red Sea trade and seek to define Syene’s position herein.

Between the Red Sea and the Nile

In the first half of the 1st century, Elephantine and Syene were administered by astratēgoswho was also in charge of Philae and the Ombite nome (stratēgos Ombeitou kai tou peri Elephantinēn kai Philas).57See Ruppel 1930, vol. III, no. 21a (after 30th of May 26?, Pselkis) and the discussion below in this paper. For the date, see Nachtergael 1999, 144. For the position of Omboi as capital of the 1st nome,cf. Dijkstra and Worp 2006.Depending on exactly where the northern border of the Ombite nome was at that time,58Jebel el-?irāj: Helck 1974, 70–71, followed by Geissen and Weber 2004, 260; Jebel al-Silsila:Locher 1999, 205.thestratēgos’ realm covered an area from below Edfū until Philae, but it probably also included the Dodekaschoinos.59Wilcken 1888, 596, n. 3 pointed out that the territory of the Dodekaschoinos belonged to Isis of Philae which becomes clear from a decree of Ptolemaios VI dated from the year 157 BC, cf. Locher 1999, App. III, no. 43. Under the Romans, and after the victory of Cornelius Gallus over those living in the Triacontaschoinos and the ruler of Meroe, the territory 30 miles beyond Syene was annexed by Rome, Bernand 1969, 128 (29 BC, Philae) = Eide et al. 1996, vol. II, nos. 163–165. It is believed that the Dodekaschoinos remained Roman territory after a new revolt and the following treaty of Samos in 21/20 BC; cf. Eide et al. 1996, vol. II, nos. 163–166 and the discussion; Eide et al. 1998,vol. III, nos. 190, 204, 205, and p. 835. This is supported, for instance, by the evidence of joint dedications from those of Philae and the Dodekaschoinos, I.Philae II 161, 4 (69–70, Philae); I.Philae II 307, 5–6 (II/III, Philae); II 179, 9–10 (213–217, Philae). A Roman milestone dating from the reign of Trajan (ca. 103–107) likewise points to an inclusion of this territory into the Roman Empire. It was found at Abu Tarfa, 67 km south of Philae, but the text which reads “a Philis XXXII” suggests that it was originally placed further north; cf. CIL III 14148. But see also Aristid. 36.48 (= Eide et al. 1998, vol. III, no. 230) who defines Philae as on the border (methorion) between Egypt and Ethiopia. It is in fact still being discussed how the Dodekaschoinos was connected to the Roman Empire; for a summary of prior scholarly opinions, see Ruppel 1930, vol. III, 77–81. He believed that the Dodekaschoinos was dependent on Upper Egypt, surmised, however, that it consisted of two toparchies (like a separate nomos). Locher 1999, 225 concluded from two ostraca (O.Bodl. II 2042;SB III 6953) which mention an anō topos tēs 12 schoinou that the nomos of Elephantine must have been divided into two different toparchies with the Dodekaschoinos as upper, and Elephantine / Syene as lower toparchy.

In an inscription from the Temple of Pselkis, an Apollonios,stratēgos tou Ombeitou kai tou peri Elephantinēn kai Philasclaimed, moreover, to have beenparalēmptēs [Er]ythras thalassēs, a receiver of imposts from the Red Sea.60OGIS 202a (= Ruppel 1930, vol. III, no. 47a = SB V 7951); Nachtergael 1999, 141–143.Whether he oversaw the entire area up to the Red Sea or just the region defined by hisstratēgia, namely the Ombite nome, that of Elephantine and Philae, is not stated. However, I would propose the latter option and will explain my reasons below.

The inscription of thisstratēgoscalled Apollonios, son of Ptolemaios (the latter probably an Arabarch)61The father’s title “Arabarch” in l. 2 is, however, only partly restored.is one of several others at the northern door of the temple. Just below it there is a second inscription that likewise mentions the presence of an Apollonios, son of Ptolemaios.62OGIS 202b (= Ruppel 1930, vol. III, no. 47b plus no. 46 with Nachtergael 1999, 142).In this second inscription Apollonios is called Tiberius Iulius Apollonios, son of Ptolemaios, Arabarch(“Arabarch” referring to Apollonios here).63Ibid., 143.It is commonly accepted in research that we are dealing with the same Apollonios as the second inscription states“the aforementioned.” Finding an adequate date for the period Apollonios wasparalēmptēsis of significance for the following arguments, so let us linger a bit on the date of the first inscription.

Georges Nachtergael convincingly argued that the second inscription written by a certain [..]ios Sēnas dates from the 3rd of May 65 since the Neronian date continues right below the inscription.64Ibid., 141–143.He dated the first inscription, mentioning Apollonios,stratēgosundparalēmptēs, to the year 60, since Sēnas noted that he came to Pselkis for the 5th time.65Ibid., 143.However, it needs to be kept in mind that Sēnas did not say he came five times together with Apollonios, neither did he say that he came five years in a row; 60 as date of the first inscription is thus disputable.

Apollonios’tria nominawould indicate that he obtained Roman citizenship under Tiberius (14–37).66Salomies 1993 discussed the question of whether new citizens could assume the name of the person who assisted them in obtaining citizenship instead of the name of the emperor. Based on onomastic reasons and on inscriptions from Asia Minor, Pontus-Bithynia, and Lycia-Pamphylia of the late 2nd and early 3rd century, he considered it in ten cases likely that either a provincial governor or a Roman senator acted as mediator. With regard to Apollonios it is remarkable, as Cuvigny 2005,14 pointed out, that he shares his praenomen and gentilicium with the later prefect Tiberius Iulius Alexander (66–69). However, that Apollonios received citizenship by Nero through mediation of the then praefectus Aegypti Tiberius Iulius Alexander seems unlikely since Alexander assumed office in 66 while Apollonios bore the nomen already in May 65. The possibility remains that Alexander acted as mediator for Apollonios earlier, for instance, during his time as epistrategos of the Thebaid in 42(OGIS 663). However, so far there is no evidence that shows whether equites could take over this intermediary role, too.The fact that his full name is not mentioned in the first inscription leaves two principal options: either Apollonios received citizenship after his “first” journey to Pselkis, or he had already obtained it, but did not mention it in the first inscription. Only in the latter case would 60 be a conceivable date for the first inscription. The latter option would, however, raise the question of why astratēgos, who in Egypt was not necessarily in possession of Roman citizenship, would not mention this status indicator.67For a discussion of the evidence of Roman citizenship among officeholders of the basilikogrammateia and the stratēgia see Kruse 2002, vol. 2, 932–936 who considers any omission of the tria nomina as rather doubtful.That this sort of relation to the emperor’s house was usually not supressed is indicated by a high number of about 84 officeholders who used theirnomen gentilebetween the Augustan period and theConstitutio Antoniniana.68Bastianini and Whitehorne 1987, discussed in Kruse 2002, vol. 2, 934.It could be taken into consideration whether the Pisonian conspiracy, which had taken place in middle of April 65, might have been a stimulus to evoke Apollonios’ belated commitment to the Julio-Claudian dynasty.69I thank Sven Günther for sharing this observation with me.However, the question is whether the information about activities in Italy reached Apollonios in time to have an impact on his decision to express his loyalty to Nero two weeks after events had taken place. And moreover, what impression might this belated confession have had on an observer who witnessed the prior omission of thetria nominain the first inscription right above the second one?

If we assume that thestratēgoshad not omitted histria nominain the first inscription it must, as a consequence, follow that Apollonios had received Roman citizenship between his “first” visit, while he wasparalēmptēs, and the second one. Since he was alreadystratēgoswhen the first inscription was written, it is probable that he was at least in his 20s.70There is no study on the sequential order of public offices held before an aspirant took over the stratēgia. Kruse 2002, vol. 2, 922–923 considered it likely that the only requirements for becoming a stratēgos were a minimum fortune and a certain social affiliation. Candidates might have even taken over the stratēgia without having served as basilikos grammateus beforehand. I thank T. Kruse for sharing his ideas on that issue with me by Email (18.09.2020).With the proposed year 65 in mind,it appears improbable that he would have become a Roman citizen in the early years of Tiberius’ reign; in such a case he would have been in his 70s at the time the second inscription was carried out. Neither the demanding journey to Pselkis nor a position as Arabarch is particularly credible at such an age. We also need to keep in mind that Apollonios’ father Ptolemaios was probably an Arabarch during the “first” visit to Pselkis.71But see n. 61.From Josephus we know that in the reign of Tiberius thearabarchiawas held by the Alexandrian Jew Alexander,72Jos. Ant. Iud. 18.6.3, 8.1; 19.5.1; 20.5.2; Bell. Iud. 5.5.3.who might have held it until Caligula, when he was imprisoned.73Jos. Ant. Iud. 19.5.1.To keep 65 as the date of the second inscription, we must thus assume that the “first” visit dated to the later years of Tiberius, but not the latest since it is likely that Alexander then was already Arabarch.

A date from the later years of Tiberius’ reign might be supported by an inscription of anotherstratēgosApollonios, son of Apollonios. This Apollonios carries the titlestratēgos [Ombeitou]74The missing Ombite is included in the title of the other inscription mentioning Apollonios, son of Apollonios; cf. Ruppel 1930, vol. III, no. 21a (Pselkis).kai tou peri E?[e]phantinēn kai Philas[kai pe]ri Thēbas kai Her?ōntheitou.75Ibid., no. 15 (Pselkis).In another inscription from the same Apollonios, the additionkai peri Thēbas kai Hermōntheitouwas no longer included in the title; it read thenstratēgos Ombeitou kai [tou] peri Elephantinēn kai Phi?[as].76Ibid., no. 21a (Pselkis).Due to the position on the wall, Nachtergael dated this second inscription (withoutkai peri Thēbas kai Hermōntheitou) to after 30th of May 26.77Nachtergael 1999, 144.J. David Thomas observed, moreover, that abasilikos grammateusof the Koptite nome and theperi Thēbasis mentioned in an ostracon dating from around 38/39 or 42/43.78Thomas 1964, 140; O.Brux 14.So apparently, after 26 and before 38/39 or 42/43 theperi Thebashad already been placed under the administration of a separatestratēgos.79For the nome peri Thēbas and its development from Ptolemaic to Roman times, cf. Thomas 1964.The titlestratēgos tou Ombeitou kai tou peri Elephantinēn kai Philas(withoutkai periThēbas kai Hermōntheitou), which also theparalēmptēsof the Red Sea carries,would thus have come into being between 30th of May 26 and 38/39 or 42/43.In a scenario in which Apollonios did not omit histria nominaand with regard to the limited time frame provided by receiving his citizenship, theterminus post quemfor the first inscription must be the year 26 and theante quemthe end of Tiberius’ reign. Under these circumstances, this would also be the proposed date for the assessment of imposts from the Red Sea in the Ombite nome, that of Elephantine and Philae, by theparalēmptēsApollonios.

Let us now take a closer look at the functions of aparalēmptēs. The first dateable, albeit indirect evidence for aparalēmptēsbeing active in the Red Sea or the Eastern Desert trade dates from 49. It is a dedicatory inscription from Berenike set up by agrammateus paralēmpseōs80For the otherwise unattested writing in Roman times, cf. Ast and Bagnall 2015, no. 1 at p. 172,comm. 4. The term paralēpsis is found in Ptolemaic terminology where it was used for receiving goods and imposts; see, for instance, ?ajtar 1999, 53, l. 8 and comm.to Isis Berenike.81Ast and Bagnall 2015, no. 1 (49, Berenike).However, no description of the scope of his duties is given. The next meaningful evidence is an inscription from Koptos dating to 103 and mentioning aparalēmptēsClaudius Chrysermos.82Bernand 1984, no. 70, 5–6 (103, Koptos), and the discussion in Ast and Bagnall 2015, 177–178.Here we receive the additional information that he was alsostratēgos(of Koptos).83Since the office did not receive any further explanation in the inscription, Claudius probably held the stratēgia in the nome where the inscription was set up.Two ostraca from around 108 mention aparalēmptēswho was probably stationed at Myos Hormos: one mentions him issuing a diploma for a certain Modestus addressing thecuratores praesidiorum, most probably in order to arrange for guards for Modestus.84O.Krok. I 1, 26–28 (108).The other ostracon is unpublished, but described by Hélène Cuvigny as a kind of sailing permit issued by theparalēmptēsfor a private individual.85O.MyHo. inv. 512 mentioned by Cuvigny 2014a, 171–172 with n. 21 and in a video-lecture given at the Collège du France: http://www.college-de-france.fr/site/jean-pierre-brun/seminar-2013-12-03-10h00.htm (14.04.2021).Theparalēmptēswas thus not only a receiver of imposts, but also a controller of movements, as pointed out by Rodney Ast and Roger Bagnall.86Ast and Bagnall 2015, 181.The latest known and dateable example of aparalēmptēsfrom Egypt is Gaius Iulius Faustinus,paralēmptēsBereneikēs,who in 112 was honoured with a statue by the secretary of the spice magazine of Berenike (apothēkē arōmatikē).87Ibid., no. 2.

Accordingly,paralēmptaiinvolved in the Red Sea trade operated at significant stations where cargo arrived, where imposts were levied, and movements controlled. Whileparalēmptaiwithout any additional office-holding were in charge at Berenike and Myos Hormos (who, however, seem to have had secretaries), the so far knownparalēmptaiin Koptos and the Ombite nome,that of Elephantine and Philae, werestratēgoi. The observation that they were responsible for the region where they were stationed supports the assumption that the scope of duties of Apollonios,paralēmptēsof the Red Sea, was likewise limited to the area in which he held his office. If there ever was aparalēmptēswho was in charge of all Red Sea imposts, he would probably have been stationed at Koptos rather than in the Ombite nome to which Elephantine and Philae belonged.

The existence of aparalēmptēsof the Red Sea trade for the region south of Koptos allows us to propose that not all cargo that arrived at a Red Sea port took the route to the Nile via Koptos. It follows as a consequence that not all commodities from the Red Sea trade were necessarily taxed in Koptos. In fact,our main information that goods entering Egypt were assessed with the quarter tax (tetartē) at Koptos comes from the so-called Muziris papyrus, a maritime loan involving goods that travelled on to Alexandria.88Discussed by De Romanis 2012; Morelli 2011; Rathbone 2000 and 2002; Casson 1986 and 1990;Thür 1987.This cargo was probably sealed and thus distinguished from commodities that remained for sale in Egypt.89See the discussion in Schmidt 2018, 89–90 with further literature.How cargo was fiscally treated that did not take the Koptos route possibly entering the Roman Empire via the First Cataract is yet not known. The existence of a spice magazine in Berenike – and probably also a market in this town90O.Ber. 1, p. 12. O.Ber. II, p. 6, and the discussion in Schmidt 2018, 90.– supports at least the suggestion that imposts could have been levied already at the port and not only in Koptos.91Ast and Bagnall 2015, 181.As a consequence, theparalēmptēsof imposts of the Red Sea may have been in charge of supervising the routes south of Koptos making sure that no cargo travelled to or in southern Egypt without being taxed.

How long an official with the titleparalēmptēsof the Red Sea existed in the firstnomoscannot be determined – in fact this is the only mention of this title. This suggests that at some point his responsibilities may have been taken over by another official. This could have been, for instance, the Arabarch who was responsible for tolls and customs in Egypt – that is, the very position Apollonios held after having beenparalēmptēs. In the second half of the 1st century, probably before 89–91, there is evidence of anepistratēgosof the Thebais who was likewise Arabarch.92Claudius Geminus, epistratēgos of the Thebais, claimed to have been Arabarch at the same time that he held the equestrian office (arabarchēs kai epistratēgos Thēbaidos), probably before 89–91 since he was identified with an idios logos of that time: OGIS 685 (before 89–91?, Memnonia). For the date, see SEG XVIII 646, l. 11; Fraser and Nicholas 1962 and 1958.He was in charge of the entire Thebais and might therefore have also taken over corresponding responsibilities of theparalēmptēsstationed in the firstnomos.93The position of the Arabarch and its relation to the paralēmptēs will be discussed in an article that the author of this paper is preparing together with L. Berkes.The incorporation of the position of theparalēmptēsof the firstnomosinto thearabarchiamay, however, have taken place also earlier, namely at the time when Apollonios, the formerparalēmptēs,became Arabarch. Under these conditions, Apollonios could have been (the first and?) the lastparalēmptēsof the firstnomos.

Syene / Elephantine and the Red Sea trade

At this point we need to come back to the question of which route(s) trade may have followed in order to reach the firstnomos. Both the Berenike-Koptos-Syene route and the direct way from Berenike to Syene are possible scenarios.However, it cannot be excluded that cargo entered Egypt from ports located south of Berenike or from the Dodekaschoinos. The mining activities that since Pharaonic times took place in Wādī al-?Allāqi and the Hills of the Red Sea let us assume a dense network of natural paths through thewādīs.94Klemm and Klemm 2013, 340–371 and 624: App. B I (Red Sea Hills); for ?Aydhab cf. Peacock and Peacock, 2008; for ?Aydhāb and Wādī al-?Allāqi, cf. Power 2012, 158–163.However, a direct connection between Syene and the Red Sea via the coastal hinterland can only be verified for Islamic times when the coastal town of ?Aydhāb, located ca. 200 km south of Berenike, operated as “the port of Aswān.”95Power 2012, 17; Garcin 2005, 48–49. Maqrīzī (Wiet 1911), I, ch IV, 8 (p. 57), specifies that the distance between Aswān and ?Aydhāb was 15 mar?alat. A mar?alat means a day trip but can also indicate a stage of a journey. Different information about the length of this journey is given by Ibn?awqal and Muqaddasī, cf. Maqrīzī (Wiet 1911), I, ch IV, 8 (p. 57), n. 18.

The unavoidable question is now: are there any documents from Syene /Elephantine that testify to imported or exported goods which can be related to trade via the Red Sea ports? The answer is both, yes and no. The first clear evidence of imports arising from long distance trade does not appear before the 4th–5th century in the form of a list of goods including balsam and pepper.96O.Eleph. DAIK 317. For the trade with pepper between India and Egypt, see De Romanis 2012;Morelli 2011.However, it is unclear whether these commodities reached the region directly from the Red Sea ports or via private suppliers from within Egypt.97For the trade with pepper in Egypt and the impact of social networks, see, most recently, Schmidt 2018.

Tax receipts, which are numerous for the first two centuries of early Roman Syene / Elephantine, are likewise not indicative of any exotic commodities that may have entered the region. The only perceivable import / export fee is a two percent tax levied bytelōnaiorepitērētai pentēkostēs limenos Soēnēs.98The pentēkostōnai limenos Soēnēs in SB V 7579, 2 are probably also < telōnai> pentēkostēs; cf.BL IX, 248.The tax was paidad valoremon the import and export of, for instance, Aswān pottery(lagynoi) flax, dates, animals, wheat, and other foodstuffs.99WO II 35 (89); SB V 7526 (89); ZPE 209 (2019), p. 217 no. 1 (92); WO II 43 (95–96); SB V 7579(100?); O.Eleph. DAIK 56 (106-114); APF 63 (2017), p. 63, no. 3 (115); SB V 7580 (128); P.Brook.64 (129); WO II 150 (129); O.Eleph. DAIK 57 (129?); O.Eleph. DAIK 58 (144); O.Cair. GPW 83 (144);O.Strasb. I 250 (138–161).The nature of thepentēkostēis still being discussed, but it was an internal tariff, probably paid for crossing the border of anomos.100J?rdens 2009, 382; Wallace 1938, 270; W.Chr. 463, col. II, 10–14 (94, Alexandria or Philadelphia).The question of whether its assessment area comprised the entire firstnomos, including the Ombite nome and the Dodekaschoinos, or “just” Syene and its hinterland, is still to be resolved.101For a discussion, see Schmidt forthcoming.

There is now, however, one ostracon that may tentatively indicate that goods from foreign trade had entered the twelve miles’ land. However, the fragmentary condition of the text impedes a comprehensive understanding of its content mentioning some kind of impost. The ostracon that dates from the 2nd / 3rd century was issued byepitērēt(ai) eidō?[n anō102The restored anō finds a parallel in another ostracon from Pselkis: […] kai anō topou tēs (Dōdeka)schoinou; cf. SB III 6953, 2 (2nd half II/III, Pselkis).to(?)]pou ē?? 12 schoino(u)?[d]ik(ēs) ????[ēs], overseers of taxes of the Upper Dodekaschoinos.103O.Bodl. 2042, 3–5 (2nd half II/III, Pselkis) (= Préaux 1951, 152–155 (3001+3002)).Although it was found in Pselkis, the editor Claire Préaux convincingly argued that it originated from Syene / Elephantine.104Préaux 1951, 153.Not only is it made of the typical Aswān pink clay, one of the issuers, Sansnōs, son of Papremeithēs, may even be identical with apraktōr argyrikōnof this name known from Elephantine.105WO II 292, 1 (II, Elephantine).If the reading is correct, the overseers were in charge of imposts from trade with theIndika Thalassawhich usually refers to the Indian Ocean properly.106See the compilation of terms used for the “Indian Ocean” by Greek and Latin authors in Sidebotham 1986, App. A.The object of taxation for which it was issued is lost or was not mentioned on the receipt.The imposteidos, included in the title of the overseers, counts among the transfer taxes and is a generic term for many different transactions such as, for instance,sales of movable and immovable property.107Wilcken 1970, 182–185.Préaux observed that in Syene /Elephantine, it is most often found in combination with thehormophylakia.108Préaux 1951, 154; Wilcken 1970, 191–192. Examples are WO 262, 3 (145); 263, 1–2 (169–177);274, 2 (185); 277, 2 (187–188); O.Strasb. I 274 (probably after 4.10.145 since WO II 262 (4.10.145)seems to be the first receipt that was issued by misthōtai and not ascholoumenoi).Firstattestedin145,misthōtaieidous hormophylakiaslevied an impost onshipownersor sailorsfor theircargoscalledenormion.109WO II 262, where enormion is missing, but see WO II 263; 274. Before this time, it was collected from ascholoumenoi tēn hormophylakian Soēnēs and most often called enormion agōgiōn. It was probably collected monthly, which is evident from WO II 262, a receipt for 3 agōgai for the current month of Thoth. Thus, cargo was taxed as a whole, not ad valorem. The quota for the tax was probably defined by a symphōnia, mentioned in some receipts; cf. SB XX 15046, 6 (120), 15047,5 (120), and APF 63 (2017), p. 95, no. 4, 6 (119). See also the commentary by Shelton 1990, 225,comm. l. 6. For the tax, cf. Wallace 1938, 275; Wilcken 1970, 273–274. For enormion agōgiōn:WO II 302 (107?); Wilcken corrected the numeral alpha into iota alpha, but in this way, Antonios Malchaios’ career would have been interrupted by Hermonax from O.Berl. 32 (29.08.–26.12.108),whose office is not mentioned, but who issues a receipt for enormia. Could WO II 302 date after Hermonax’s office? In the as yet published texts, Antonios Malchaios appears otherwise uninterrupted until 25.4.120; cf. SB XX 15046); O.Bankes 4 (107–120? possibly later than 26.12.108, see comm. to WO II 302); O.Bankes 5 (107–120? possibly after 108, cf. above to WO II 302); WO II 303 (114/115?);304 (115); 1276 (98–117? possibly after 108, cf. above to WO II 302, and at least until 25.4.120,cf. SB XX 15046); O.Eleph. DAIK 21 (after 23.08.118); APF 63 (2017) p. 95 no. 4 (119); SB XVIII 13205 (119); SB XX 15046 (25.4.120); 15047 (120?); O.Brux. 4 (after 25.4.120?); P.Brook. 65 (II).Theeidoscollected bythe overseers of taxes pertaining to the Dodekaschoinos may thus have been levied in association with a change in ownership, transit, or trade in general. Additionally,if the restorationIn[d]ik(ēs) thalass[ēs]is correct, it could have been connected with the trade of goods from the Indian Ocean that entered the Dodekaschoinos;from where remains unclear, but it is noteworthy that the tax receipt does not include the import tax of 25 percent (tetartē) which was levied on commodities that entered the Roman Empire. The absence of thetetartēcould be explained by assuming that such goods from the Indian trade had paid the tax already at the Red Sea ports or in Koptos before travelling on to the Dodekaschoinos via Syene. However, would it in this case indeed be necessary to additionally employ overseers of taxes of the Upper Dodekaschoinos in Syene that controlled taxes pertaining to the Indian Ocean trade? This leads us back to the more general question: Where was the import tax of 25 percent levied on commodities that entered the Empire somewhere south of the Berenike-Koptos connection and that remained in Upper Egypt or the Dodekaschoinos? We still have no information on how products that did not travel on to Alexandria were treated.110For goods that travelled on to Alexandria the Muziris papyrus shows that the tetartē was not levied at the ports, but in Koptos (although it might finally have been paid only in Alexandria). On this most recently: De Romanis 2020, 305; Morelli 2011, 232; J?rdens 2009, 366; Burkhalter 2002,203; Rathbone 2002, 183–184.Did merchants have to pay thetetartēfor this as well, or did they pay only internal tariffs for crossing the border of anomos? There is as yet no final answer to these questions.111Young 1997 suggested that only luxury goods paid the tetartē while, for instance, frankincense and myrrh were exempt from such payments since as religious items they were not “l(fā)uxury imports.”He based his argument on the observation that Plin. NH 12.32 (65) did not mention a 25 percent tax at Gaza for these products, dismissed, however, that the same author gave a detailed overview of additional costs for transport and fees (688 denarii per camel) which added to the final price of frankincense of about 3 to 6 denarii per pound. Young’s argument had already been rejected by Rathbone 2000, 45, but endorsed again by Vandorpe 2015, 92.The ostracon from Pselkis shows at least that Syene had taken over fiscal responsibilities for commercial activities in the Dodekaschoinos.Whether this also included trade with Indian Ocean commodities that entered the Empire via a direct connection from the Red Sea towards Syene or by the Dodekaschoinos can ultimately not be stated until further papyri or ostraca surface that confirm a tax on Indian trade goods levied in Syene / Elephantine.

To sum up: Relations and interdependences in the First Cataract region are still not fully explored and understood. A better understanding of the development of this region, which in Muslim Egypt would become a major southern trade centre, requires further investigation; in particular, regarding interrelations with Nubia, but also potential connections to the Red Sea that in Muslim times are reflected by the establishment of the port of ?Aydhāb. Above all, the discussion of the ostracon from Pselkis shows how far we are from fully understanding trade connections in the southernmost border region of Roman Egypt.112The economic development of Aswān and its interrelations is currently being investigated by a DFG-project at the Free University of Berlin, headed by the author of this article. Interrelations between Aswān and Kom Ombo are currently studied by a FWF-project (Einzelprojekt P 31791) at the Archaeological Institute in Vienna / Cairo, headed by Irene Forstner-Müller.It is clear that those cannot be seen in isolation from regulations set in place at the Red Sea ports where commodities may have been taxed in the first place. In addition, the example of theparalēmptēsof the Red Sea allows us to assume that conditions were set in place for taxing goods entering the Ombite nome,that of Elephantine and Philae from the Red Sea trade. This may have been the case at least in the second and third quarters of the 1st century, more precisely,between 26 and the appearance of theepistratēgosof the Thebais who was likewise Arabarch (probably before 89–91), or already earlier when Apollonios assumed thearabarchia(before 3rd of May 65). However, due to the fact that neither papyri nor ostraca have surfaced so far that would document the payment of the quarter tax in Syene / Elephantine, a question yet to be solved is where merchants paid thetetartēfor cargo destined for the firstnomos. Several scenarios are conceivable – it could have been paid at one of the Red Sea ports,in Koptos, or in the Dodekaschoinos, perhaps at the town of Hiera Sykaminos at its southernmost border. A further possibility is that cargo from the long-distance trade that remained in Egypt did not pay the quarter tax at all, but just internal tariffs. Further studies are needed in order to provide more clarity on this issue.

Bibliography

Adamietz, J. 1993.

Juvenal, Satiren. Lateinisch-deutsch. Sammlung Tusculum. Munich & Zurich:Artemis und Winkler.

Adams, W. Y. 1986.

Ceramic Industries of Medieval Nubia. 2 vols. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Ast, R. and Bagnall, R. S. 2015.

“The Receivers of Berenike. New Inscriptions from the 2015 Season.”Chiron45: 171–185.Ballet, P. 1996.“De la Méditerranée à l’océan indien. L’égypte et le commerce de longue distance à l’époque romaine. Les données céramiques.”Topoi orient-occident6/2: 809–840.—— 1998.

“Cultures matérielles des déserts d’égypte sous le Haut et le Bas-Empire:Productions et échanges.” In: O. E. Kaper (ed.),Life on the Fringe. Living in the Southern Egyptian Deserts during the Roman and Early-Byzantine Periods.Leiden: CNWS Publications, 31–54.—— 2018.

“Pottery from the Wadi al-Hammamat. Contexts and Chronology (Excavations of the Institut fran?ais d’archéologie orientale 1987–1989.” In: Brun et al. 2018,547–561.

Barbier de Meynard, C. and Pavet de Courteille, A. 1861–1877.

Al-Mas?ūdī, Kitāb murūj al-dhahab/Les prairies d’or. 9 vols. Paris: Imprimerie Impériale.

Bastianini, G. and Whitehorne, J. E. G. 1987.

Strategi and Royal Scribes of Roman Egypt. Chronological List and Index(Pap.Flor. 15). Florence: Gonnelli.

Bernand, A. 1969.

Les inscriptions grecques et latines de Philae. vol. II:Haut et Bas Empire. Paris:éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.—— 1972a.

Le paneion d’El-Kana?s: Les inscriptions grecques. Leiden: Brill.—— 1972b.

De Koptos à Kosseir.Leiden: Brill.—— 1977.

Pan du désert. Leiden: Brill.—— 1984.

Les portes du desert. Recueil des inscriptions grecques d’Antinooupolis, Tentyris,Koptos, Apollonopolis Parva et Apollonopolis Magna. Paris: CNRS.—— 1989.

De Thèbes à Syène. Paris: CNRS.

Bernand, A. and Masson, O. 1957.

“Les inscriptions grecques d’Abou Simbel.”Revue des études Grecques70: 1–46.Bricault, L. 1999.

“Sarapis et Isis sauveurs de Ptolémée IV à Raphia.”Chronique d’égypte74:334–343.

Brun, J.-P. 1994.

“Le faciès céramique d’Al-Zarqa. Observations préliminaires.”Bulletin de l’Institut fran?ais d’archéologie orientale94: 7–26.—— 2007.

“Amphores égyptiennes et importées dans les praesidia romains des routes de Myos Hormos et de Bérénice.”Cahiers de la Céramique égyptienne8/2: 505–523.

—— 2018.

“Chronology of the Forts of the Routes to Myos Hormos and Berenike during the Graeco-Roman Period.” In: Brun et al. 2018, 141–181.

Brun, J.-P. et al (eds.). 2018.

The Eastern Desert of Egypt during the Greco-Roman Period: Archaeological Reports. Paris: Collège de France.

Burkhalter, F. 2002.

“Le ‘tarif de Coptos’. La douane de Coptos, les fermiers de l’apostolion et le préfet du désert de Bérénice.” In:Autour de Coptos: Actes du colloque organisé au Musée de Beaux-Arts de Lyon (17–18 mars 2000). Topoi orient-occident,Supplément 3. Paris: De Boccard, 199–233.

Burstein, S. M. 1996.

“Ivory and Ptolemaic Exploration of the Red Sea. The Missing Factor.”Topoi orient-occident6/2: 799–807.

Caputo, C. 2019.

“Looking at the Material. One Hundred Years of Studying Ostraca from Egypt.”In: C. Ritter-Schmalz and R. Schwitter (eds.),Antike Texte und ihre Materialit?t.Allt?gliche Pr?senz, mediale Semantik, literarische Reflexion. Berlin: De Gruyter, 93–117.

Casson, L. 1986.

“P. Vindob. G 40822 and the Shipping of Goods from India.”Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists23: 73–79.—— 1989.

The Periplus Maris Erythraei. Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton: Princeton University Press.—— 1990.

“New Light on Maritime Loans. P. Vindob. G 40822.”Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik84: 195–206.—— 1993.

“Ptolemy II and the Hunting of African Elephants.”Transactions of the American Philological Association123: 247–260.

Cobb, M. A. 2016.

“The Decline of the Ptolemaic Elephant Hunting. An Analysis of the Contributory Factors.”Greece & Rome63/2: 192–204.

Cuvigny, H. 2005.

Ostraca de Krokodil?. La correspondance militaire et sa circulation. O. Krok.1–151. Praesidia du désert de Bérénice II.Cairo: Institut fran?ais d’archéologie orientale.—— 2014a.

“Papyrological Evidence of ‘Barbarians’ in the Egyptian Eastern Desert.” In:J. H. F. Dijkstra and G. Fisher (eds.),Inside and Out. Interactions between Rome and the Peoples on the Arabian and Egyptian Frontiers in Late Antiquity.Leuven et al.: Peeters, 165–198.—— 2014b.

“La plus ancienne représentation de Mo?se, dessinée par un juif vers 100 apr. J.-C.”Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres158/1:339–351.

Dijkstra, J. H. F. and Worp, K. A. 2006.

“The Administrative Position of Omboi and Syene in Late Antiquity.”Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik155: 183–187.

De Romanis, F. 2012.

“Playing Soduko on the Verso of the ‘Muziris Papyrus’. Pepper, Malabathron and Turtoise shell in the Cargo of theHermappolon.”Journal of Ancient Indian History27: 75–101.—— 2020.

The Indo-Roman Pepper Trade and the Muziris Papyrus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Desanges, J. 1970.

“Les chasseurs d’éléphants d’Abou-Simbel.” In:Actes du 92e Congrès national des sociétés savants, Strasbourg et Colmar 1967. Section d’archéologie. Paris:Bibliothèque Nationale, 31–50.

Dzwoneck, A. 2017.

“Pottery from the Early Roman Rubbish Dumps in Berenike Harbor.” In: C. Guidotti and G. Rosati (eds.),International Congress of Egyptologists 11, Florence,Italy 23–20 August 2015.Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, 711–713.

Eide, T. et al. 1994–2000.

Fontes Historiae Nubiorum. Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD. 4 vols.Bergen: University of Bergen.

Fakhry, A. 1952.

The Inscriptions of the Amethyst Quarries at Wadi al Hudi. Cairo: Gov. Press.

Fraser, P. M. and Nicholas, B. 1958.

“The Funerary Garden of Mousa.”The Journal of Roman Studies48/1–2: 117–129.—— 1962.

“The Funerary Garden of Mousa Reconsidered.”The Journal of Roman Studies52/1–2: 156–159.

Fünfschilling, S. 2017.

“Ausgew?hlte Funde aus Buntmetall, Elfenbein, Ton und Eisen.” In: S. Martin-Kilcher and J. Wininger (eds.),Syene III. Untersuchungen zur r?mischen Keramik und weiteren Funden aus Syene/Assuan (1.–7. Jahrhundert AD).Grabungsberichte 2011–2004. Gladbeck: PeWe-Verlag, 355–359.

Garcin, J.-C. 2005.

Qū?. Un centre musulman de la Haute-égypte médiévale.Cairo: Institut Fran?ais d’Archéologie Orientale.

Gates-Foster, J. E. 2019.

“Pottery from the Surveys.” In: Sidebotham and Gates-Foster 2019, 287–375.

Geissen, A. and Weber, M. 2004.

“Untersuchungen zu den ?gyptischen Nomenpr?gungen II: 1.–7. Ober?gyptischer Gau.”Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik147: 259–280.

Gempeler, R. D. 1992.

Elephantine X. Die Keramik r?mischer bis früharabischer Zeit.Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

Goedicke, H. 1981.

“Harkhuf’s Travels.”Journal of Near Eastern Studies40/1: 1–20.

Graeff, J.-P. 2005.

Die Stra?en ?gyptens. Berlin: dissertation.de – Verlag im Internet GmbH.

Helck, W. 1974.

Die alt?gyptischen Gaue. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

Herbert, S. C. and Berlin, A. 2003.

“The Excavation: Occupation History and Ceramic Assemblages.” In: eid. (eds.),Excavations at Coptos (Quift) in Upper Egypt 1987–1992. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplements 53. Michigan: Thomson-Shore, 12–156.

Highet, G. 1937.

“The Life of Juvenal.”Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 68: 480–506.

Hu?, W. 2001.

?gypten in hellenistischer Zeit: 332–30 v. Chr.Munich: C. H. Beck.

Jacquet-Gordon, H. 1985.

“A Group of Egyptian Figure Painted Bowls of the Roman Period.” In: P. Posener-Kriéger (ed.),Melanges G. E. Mokhtar.vol. 1. Bibliothèque d’étude 97/1. Cairo:Institut Fran?ais d’Archéologie Orientale, 409–417.

Jaritz, H. 1998.

“Eine Elefantenstatue aus Syene – Gott oder Gott-geweiht?” In: H. Guksch and D. Polz (eds.),Stationen. Beitr?ge zur Kulturgeschichte ?gyptens. Festschrift R. Stadelmann. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 459–467.

J?rdens, A. 2009.

Statthalterliche Verwaltung in der r?mischen Kaiserzeit. Studien zumpraefectus Aegypti. Historia Einzelschriften 175. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Keimer, L. 1952–1953.

“Die ptolem?ische oder r?mische Elefanten-Statue in Wien.”Archiv für Orientforschung16: 268–271.

Klemm, R. and Klemm, D. 2013.

Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia. Heidelberg: Springer.

Komorzynski, E. 1952–1953.

“Eine Elefanten-Statue in der ?gyptisch-Orientalischen Sammlung des Kunsthistorischen Museums in Wien.”Archiv für Orientforschung16: 263–268.—— 1954–1956.

“Nachtrag zu dem Aufsatz über die Elefanten-Statue in Wien.”Archiv für Orientforschung17: 48.

Kruse, T. 2002.

Der K?nigliche Schreiber und die Gauverwaltung. Untersuchungen zur Verwaltungsgeschichte ?gyptens in der Zeit von Augustus bis Philippus Arabs(30 v.Chr. – 245 n.Chr.).2 vols. Archiv für Papyrusforschung Beiheft 11/1–2.Munich & Leipzig: Saur.

?ajtar, A. 1999.

“Die Kontakte zwischen ?gypten und dem Horn von Afrika im 2. Jh. v. Chr. Eine unver?ffentlichte griechische Inschrift im Nationalmuseum Warschau.”Journal of Juristic Papyrology29: 51–66.

Locher, J. 1999.

Topgraphie und Geschichte der Region am Ersten Nilkatarakt in griechischr?mischer Zeit. Stuttgart & Leipzig: Teubner.

McCabe, D. F. 1985.

Didyma Inscriptions. Texts and List. The Princeton Project on the Inscriptions of Anatolia. Princeton: The Institute for Advanced Study.

Mairs, R. 2013.

“Intersecting Identities in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt.” In: R. J. Dann and K. Exell (eds.),Egypt: Ancient Histories, Modern Archaeologies. New York:Cambria Press, 163–192.

Mayer, W. 1981.

“Felszeichnungen bei Assuan.”Mitteilungen des Deutschen Arch?ologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo37: 313–314.

Maxfield, V. A. 2000.

“The Deployment of the Roman Auxilia in Upper Egypt and the Eastern Desert during the Principate.” In: G. Alf?ldy, B. Dobson and W. Eck (eds),Kaiser,Heer und Gesellschaft in der R?mischen Kaiserzeit.Heidelberger althistorische Beitr?ge und epigraphische Studien 31. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 497–442.

Morelli, F. 2011.

“Dal Mar Rosso ad Alessandria. Il verso (ma anche il recto) del ‘papiro di Muziris’ (SB XVIII 13167).”Tyche26: 199–233.

Müller, W. 2013.

“Hellenistic Aswan.” In: D. Raue, S. J. Seidlmayer and P. Speiser (eds.),The First Cataract of the Nile. One Region – Diverse Perspectives. Berlin: De Gruyter, 123–133, pls. 26–28.

Muhs, B. P. 2005.

Tax Receipts, Taxpayers, and Taxes in Early Ptolemaic Thebes.Oriental Institute Publications 126. Chicago: The Oriental Institute.

Nachtergael, G. 1982.

“Rev. of Scritti in onore di O. Montevecchi.”Chronique d‘égypte57: 173–180.—— 1999.

“Retour aux inscriptions grecques du Temple de Pselkis.”Chronique d‘égypte74: 133–147.

Peacock, D. and Peacock, A. 2008.

“The Enigma of ‘Aydhab: a Medieval Islamic Port on the Red Sea Coast.”The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology37/1: 32–48.

Power, T. 2012.

The Red Sea from Byzantium to the Caliphate. AD 500–1000.Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

Préaux, C. 1951.

“Ostraca de Pselkis de la Bibliothèque Bodléene.”Chronique d‘égypte26: 121–155.

Rathbone, D. 2000.

“The ‘Muziris’ Papyrus (SB XVIII 13167). Financing Roman Trade with India.”Bulletin de la Société d’Archaeologie d’Alexandrie46: 39–50.—— 2002.

“Koptos theemporion. Economy and Society, I–III AD.”Topoi orient-occident3:179–198.

Redon, B. 2018.

“The Control of the Eastern Desert by the Ptolemies. New Archaeological Data.”In: Brun et al. 2018, 29–49.

Roccati, A. 1981.

“Iscrizioni greche da File.” In: E. Bresciani et al. (eds.),Scritti in onore di O. Montevecchi. Bologna: Clueb, 323–333.

Rodziewicz, M. D. 2005.

Elephantine XXVII. Early Roman Industries on Elephantine.Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

Ruppel, M. W. 1930.

Der Tempel von Dakke.vol. 3. Cairo: Institut Fran?ais d’Archéologie Orientale.Salomies, O. 1993.

“R?mische Amtstr?ger und r?misches Bürgerrecht in der Kaiserzeit. Die Aussagekraft der Onomastik (unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der kleinasiatischen Provinzen).” In: W. Eck (ed.),Prosopographie und Sozial-geschichte. Studien zur Methodik und Erkenntnism?glichkeit der kaiserzeitlichen Prosopographie.Cologne: B?hlau Verlag, 119–145.

Schmidt, S. 2018.

“‘(…) und schicke mir 10 K?rner Pfeffer’. Der Binnenhandel mit Pfeffer im r?mischen, byzantinischen und frühislamischen ?gypten.” In: K. Ruffing and K. Dro?-Krüpe (eds.),Emas non quod opus est, sed quod necesse est. Beitr?ge zur Wirtschafts-, Sozial-, Rezeptions-und Wissenschaftsgeschichte der Antike.Festschrift für H.-J. Drexhage zum 70.Geburtstag. Philippika 125. Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz, 85–105.—— forthcoming.

“Viel Verpackung, wenig Trauben – überlegungen zum Weinanbau und -handel im r?mischen Syene.”

Seland, E. H. 2010.

Ports and Political Power in the Periplus. Complex Societies and Maritime Trade on the Indian Ocean in the First Century AD. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Shaw, I. 2007.

“Late Roman Amethyst and Gold Mining at Wadi el-Hudi.” In: T. Schneider and K. Szpakowska (eds.),Egyptian Stories A British Egyptological Tribute to A. B.Lloyd on the Occasion of his Retirement. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 319–328.

Shaw, I. and Jameson, R. 1993.

“Amethyst Mining in the Eastern Desert: A Preliminary Survey at Wadi el-Hudi.”Journal of Egyptian Archaeology79: 81–97.

Shelton, J. 1990.

“Ostraca from Elephantine in the Fitzwilliam Museum.”Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik80: 221–238.

Sidebotham, S. E. 1986.

Roman Economic Policy in the Erythra Thalassa: 30 B.C. – A.D. 217. Leiden:Brill.—— 2011.

Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route.Berkeley et al.: University of California Press.—— 2018.

“Overview of Fieldwork at Berenike 1994–2015.” In: Brun et al. 2018, 594–625.

Sidebotham, S. E. and Gates-Foster, J. E. 2019.

The Archeological Survey of the Desert Roads between Berenike and the Nile Valley. Expeditions by the University of Michigan and the University of Delaware to the Eastern Desert of Egypt, 1987–2015. Boston: American School of Oriental Research.

Sidebotham, S. E., Hense, M. and Nouwens, H. M. 2008.

The Red Land. The Illustrated Archaeology of Egypt’s Eastern Desert. Cairo &New York: The American University in Cairo Press.

Sigl, J. 2017.

Syene II. Die Tierfunde aus den Grabungen von 2000–2009. Ein Beitrag zur Umwelt-und Kulturgeschichte einer ober?gyptischen Stadt von der pharaonischen sp?t-bis in die Mameluckenzeit,2 vols. Gladbeck: PeWe.

Then-Ob?uska, J. 2016.

“Beads and Pendants from the Tumuli Cemeteries at Wadi Qitna and Kalabsha-South, Nubia.”BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers28/1: 38–49.—— 2019.

Glass Bead Trade in Northeast Africa: The Evidence from Meroitic and Post-Meroitic Nubia.Warsaw: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology.

Thissen, H.-J. 1964.

“The Theban Administrative District in the Roman Period.” TheJournal of Egyptian Archaeology50: 139–143.—— 1966.

Studien zum Raphiadekret.Beitr?ge zur klassischen Philologie 23. Meisenheim/Glan: A. Hain.

Thür, G. 1987.

“Hypotheken-Urkunde eines Seedarlehens für eine Reise nach Muziris und Apographe für die Tetarte in Alexandria.”Tyche2: 229–245.

Tomber, R. 1992.

“Early Roman Pottery from Mons Claudianus.”Cahiers de la Céramique égyptienne3: 137–142.—— 2001.

“The Pottery.” In: V. Maxfield and D. Peacock (eds.),The Roman Imperial Quarries. Survey and Excavation at Mons Porphyrites, 1994–1998. London:Egypt Exploration Society, 241–303.—— 2012.

“From the Roman Red Sea to beyond the Empire. Egyptian Ports and their Trading Partners.”British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan18: 201–215.

—— 2017.

“The Late Hellenistic and Roman Pottery.” In: A. Pavan (ed.),A Cosmopolitan City on the Arabian Coast. The Imported and Local Pottery from Khor Rori.Khor Rori Report 3. Rome: Bretschneider, 322–397.—— 2018.

“Quarries, Ports and Praesidia: Supply and Exchange in the Eastern Desert.” In:Brun et al. 2018, 562–589.—— 2019.

“The Roman Pottery from Kab Marfu?a.” In: Sidebotham and Gates-Foster 2019,377–387.

Vandorpe, K. 2015.

“Roman Egypt and the Organisation of Custom Duties.” In: P. Kritzinger,F. Schleicher and T. Stickler (eds.),Studien zum r?mischen Zollwesen. Duisburg:Wellem Verlag, 89–110.

Ve?sse, A.-E. 2004.

Les ‘révoltes égyptiennes’: Recherches sur les troubles intérieurs en égypte du règne de Ptolémée III Evergète à la conquête romaine.Studia Hellenistica 41.Leuven: Peeters.

Wallace, S. L. 1938.

Taxation in Egypt from Augustus to Diocletian. New York: Greenwood Press.

W?ngstedt, S. V. 1968.

“Demotische Steuerquittungen aus ptolem?ischer Zeit.”O(jiān)rientalia Suecana17:28–60.

Wessner, P. (ed.). 1931.

Scholia in Iuuenalem Vetustiora. Leipzig: Teubner.Wiegand, T. 1958.

Didyma. vol. 2:Die Inschriften von Albert Rehm. Ed. by R. Harder. Berlin:Verlag Gebr. Mann.

Wiet, M. G. (ed.). 1911–1927.

El-Maqrīzī, A. ibn A.,Kitāb al-mawā?i? wa?l-i?tibār fī dhikr el-khi a wa?l-āthār.5 vols. Cairo: L’Institut Fran?ais d’Archéologie Orientale.

Wilcken, U. 1970.

Griechische Ostraka aus Aegypten und Nubien. vol. I. Amsterdam: A. M. Hakkert(unchanged reprint of the edition Leipzig & Berlin: Gieseke & Devrient, 1899).—— 1888.

“Kaiserliche Tempelverwaltung in Aegypten.”Hermes23/4: 592–606.

Young, G. K. 1997.

“The Customs-Officer at the Nabataen Port of Leuke Kome (Periplus Maris Erythraei19).”Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik119: 266–268.

Fig. 1: Sidebotham 2011, fig. 8.1 (drawing by M. Hense)

Journal of Ancient Civilizations2021年2期

Journal of Ancient Civilizations2021年2期

- Journal of Ancient Civilizations的其它文章

- Editors’ Note

- REPUBLISHED TEXTS IN THE ATTIC ORATORS

- WEALTHY KOANS AROUND 200 BC IN THE CONTEXT OF HELLENISTIC SOCIAL HISTORY

- PICTORIAL ELEMENTS VS. COMPOSITION? “READING” GESTURES IN COMEDY-RELATED VASE-PAINTINGS (4TH CENTURY BC)*

- DELIAN ACCOUNTABILITY AND THE COST OF WRITING MATERIALS*