Does proximal femoral nail antirotation achieve better outcome than previous-generation proximal femoral nail?

Seung-Hoon Baek,Seunggil Baek, Heejae Won,Jee-Wook Yoon, Chul-Hee Jung, Shin-Yoon Kim

Seung-Hoon Baek, Heejae Won, Jee-Wook Yoon, Chul-Hee Jung, Shin-Yoon Kim, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu 41944, South Korea

Seung-Hoon Baek, Shin-Yoon Kim, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 41944, South Korea

Seunggil Baek, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Goodssen Hospital, Daegu 42010, South Korea

Abstract

Key Words: Pertrochanteric fracture; Proximal femoral nail; Proximal femoral nail antirotation; Sliding distance; Cutout; Outcome

INTRODUCTION

As the population continues to age, the incidence of pertrochanteric femoral fracture (PFF) has also increased[1]and surgery has been reported as a standard treatment for achieving better clinical outcomes, including shorter hospitalization, earlier return to preinjury status, and fewer complications such as bed sores, pulmonary thromboembolism, and pneumonia[2-4]. Among the numerous implants currently available for the internal fixation of PFF[5-7], proximal femoral nail (PFN; Synthes?, Solothurn, Switzerland) has been reported in the last decade to be a suitable implant for the treatment of unstable PFF in elderly patients[8-10]. However, some studies have reported several complications associated with the use of PFN, including cutout and the Z-effect[8,11,12]. To overcome these complications, a newly-designed implant, proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA; Synthes?, Solothurn, Switzerland), has been developed. According to a biomechanical study conducted in the laboratory setting, the PFNA blade compacts the cancellous bone, leading to increased stability and higher resistance to cutout in the osteoporotic bone[13]. However, there are few studies comparing clinical outcomes and radiographic results (including cutout after fixation) between elderly patients with PFF receiving PFNA and those receiving the previousgeneration PFN. Therefore, we evaluated the clinical and radiographic outcomes after fixation with PFN and PFNA for PFF in elderly patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

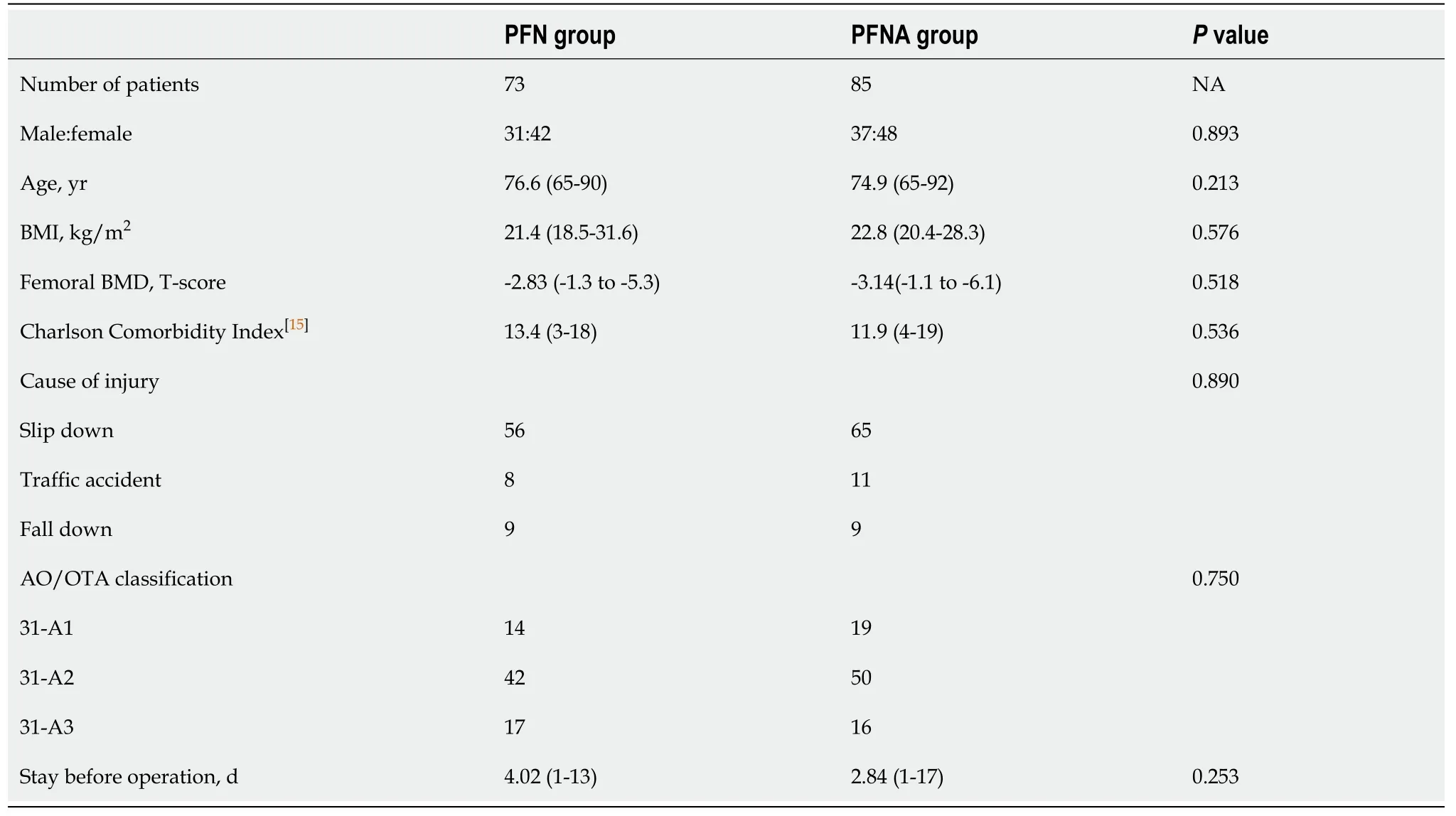

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board in our institution which waived informed consents. From January 2003 to December 2009, 204 patients over 65 years of age with PFF underwent fixation with either PFN or PFNA at a single institution. Among them, 46 patients were excluded because of bilateral PFF (2 patients) and loss to follow-up before radiographic follow-up at one year (44 patients). Thus, the remaining 158 patients were included. The mean duration of radiographic follow-up was 2.4 years (range, 1-7 years). Seventy-three patients underwent fixation with PFN (PFN group), whereas 85 patients were fixed with PFNA (PFNA group). The PFN group was composed of 31 men and 42 women with an average age of 76.6 ± 7.3 years. Based on the AO classification[14], fractures was categorized as 31-A1 in 14 patients, A2 in 42 patients, and A3 in 17 patients. The PFNA group consisted of 37 men and 48 women with an average age of 74.9 ± 7.2 years. Fractures were classified as 31-A1 in 19 patients, A2 in 50 patients, and A3 in 16 patients. We identified each patient’s medical history and converted it to a Charlson Comorbidity Index[15]score by deploying questionnaires at each patient’s visit to the clinic and conducting a careful review of medical records. In addition, femoral bone mineral density was also investigated. Demographic details and fracture characteristics are described in Table 1. There were no differences between the two groups (P> 0.05).

All operations were performed using a fracture table under the guidance of fluoroscopy. We encouraged the Q-setting exercise with an active range of motion, with wheelchair ambulation at one day after index operation. Clinical outcome was measured in terms of operation time, postoperative function according to Salvati and Wilson’s hip function rating system[16]at each patient’s visit to the clinic, and mortality rate within one year. The operation time was calculated from skin incision to closure. We searched the National Statistical Office for death certificates for patients who failed follow-up[17]. Radiographic evaluation included the reduction state after the operation, which was categorized into three groups using modified Baumgartner’s criteria[18], the Cleveland Index[19], tip-apex distance (TAD)[7], union rate, time to union and sliding distance of the screw or blade. Complications, including nonunion, screw cutout, infection, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, and implant breakage were also investigated.

The Pearson chi-square test and Studentt-test were performed for statistical analysis using SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States), and differences were considered significant when thePvalue was < 0.05. The statistical methods used in this study were reviewed by Won Kee Lee, Professor of Biostatistics of Kyungpook National University.

RESULTS

Clinical outcomes

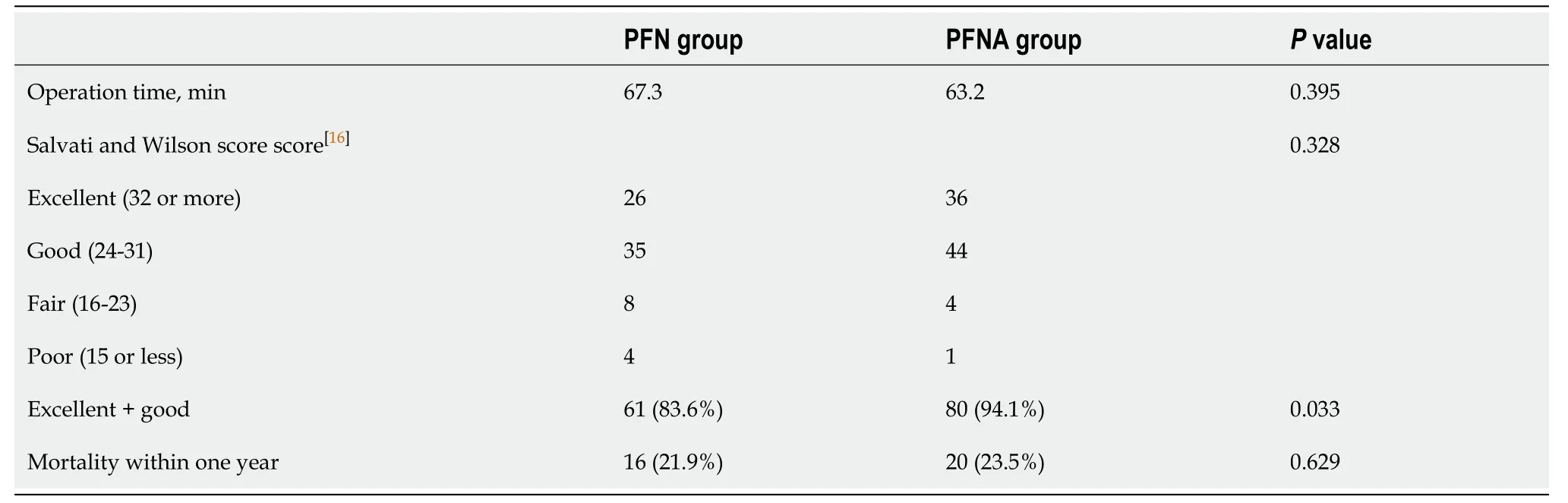

In the PFN group, postoperative hip function was graded as excellent in 26 (35.6%), good in 35 (47.9%), fair in 8, and poor in 4 patients, respectively (Table 2). In the PFNA group, hip function was classified as excellent in 36 (42.4%), good in 44 (51.8%), fair in 4, and poor in 1 patient, respectively. The proportion of patients with excellent or good postoperative function was significantly higher in the PFNA group compared to the PFN group (94.1% and 83.6%,P= 0.033). Differences in operation time and mortality within one year were not significantly different between the two groups (P> 0.05).

Radiographic outcomes

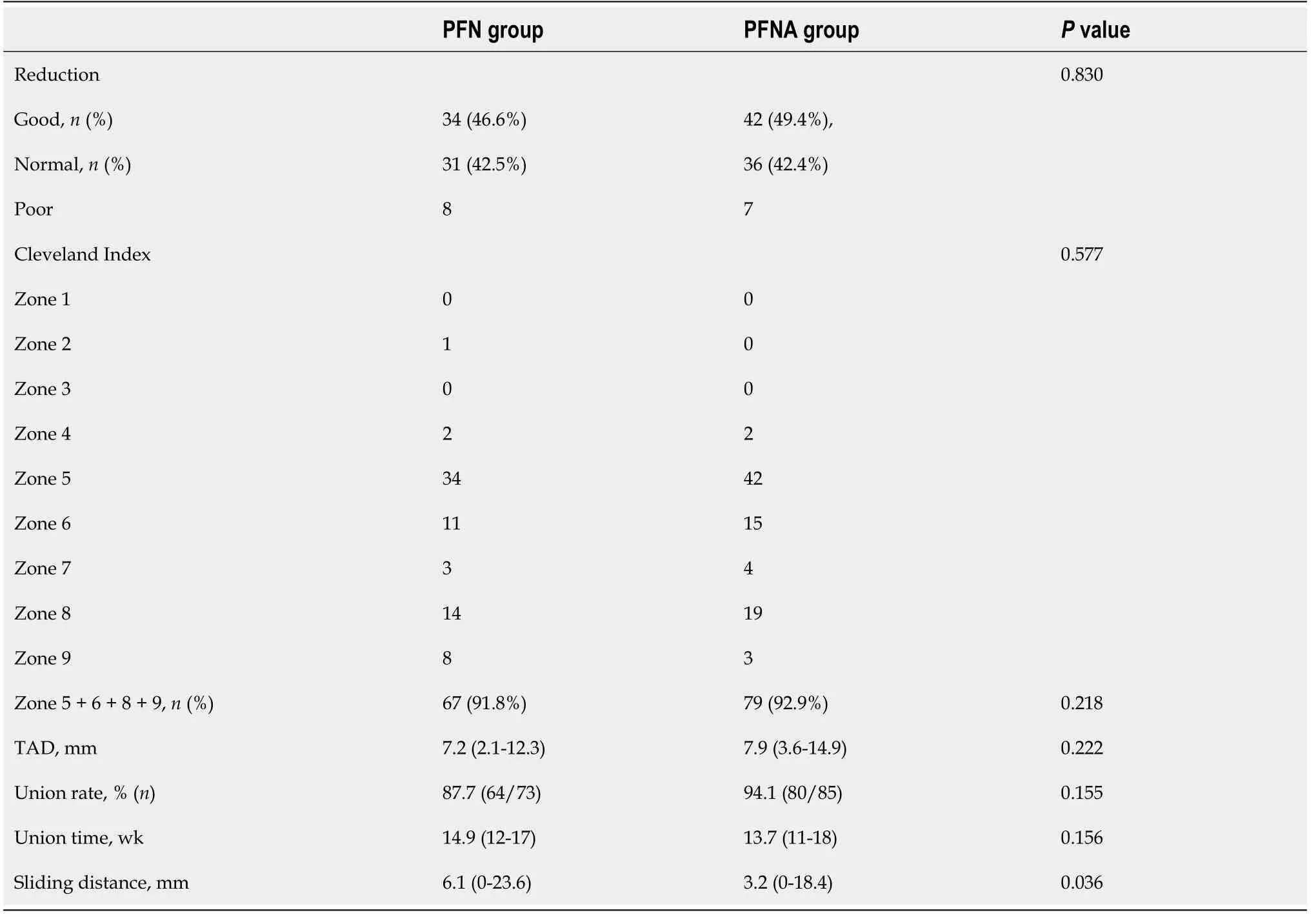

The union rate was 87.7% for the PFN group (64/73) and 94.1% for the PFNA group (80/85) (P= 0.155), and the union time was 14.9 wk (range, 12-17) and 13.7 wk (range, 11-18), respectively (P= 0.156).

In the PFN group, reduction was graded as good in 34 (46.6%), normal in 31 (42.5%), and poor in 8 patients, whereas it was rated as good in 42 (49.4%), normal in 36 (42.4%), and poor in 7 patients in the PFNA group (P= 0.830; Table 3). According to Clevelandet al[19], zones 5, 6, 8, and 9 were shown in 67 (91.8%) patients with PFN, whereas those zones were demonstrated in 79 patients (92.9%) with PFNA (P= 0.218). TAD was 7.2 mm (range, 2.1-12.3) in the PFN group, whereas it was 7.9 mm (range, 3.6-14.9) on immediate postoperative radiographs in the PFNA group.

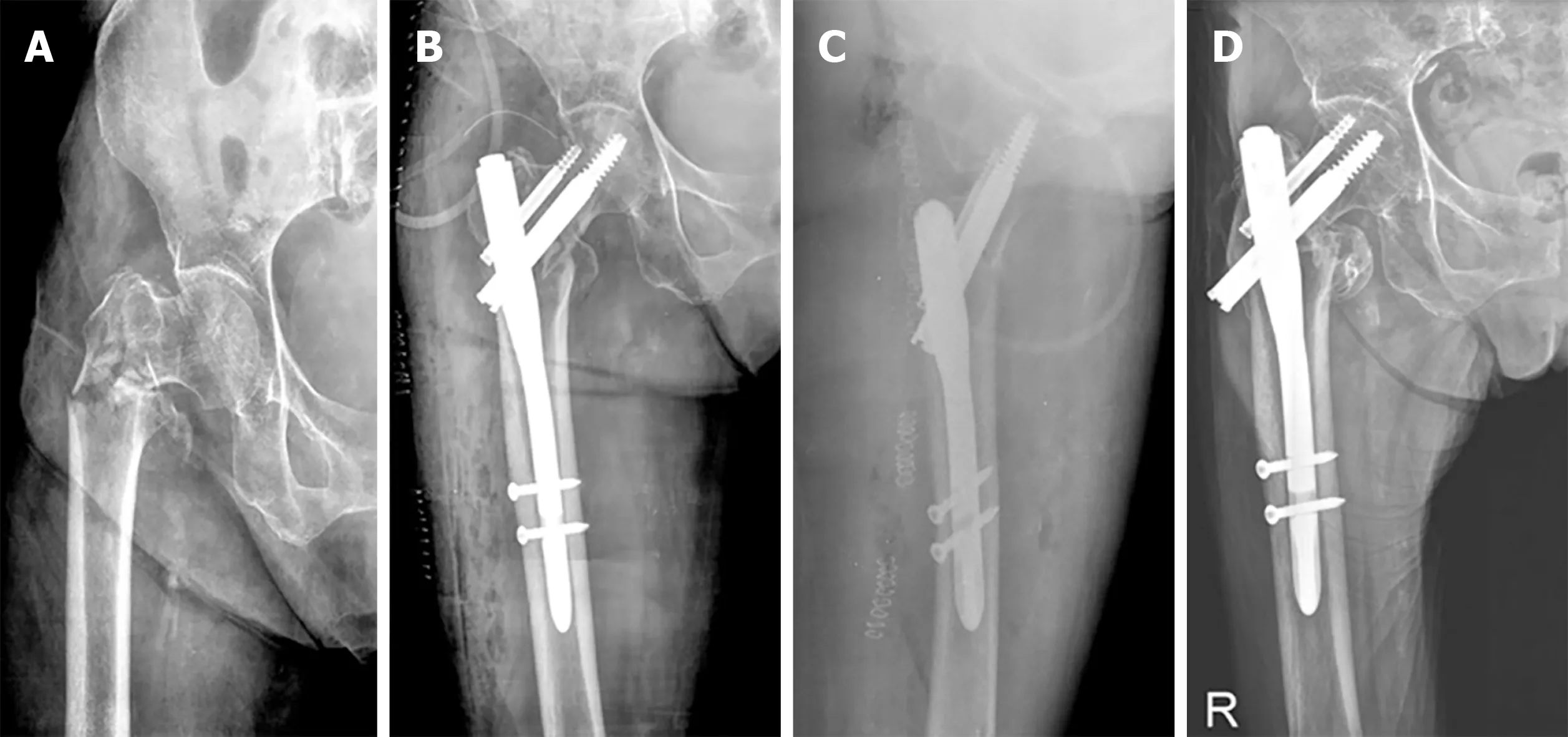

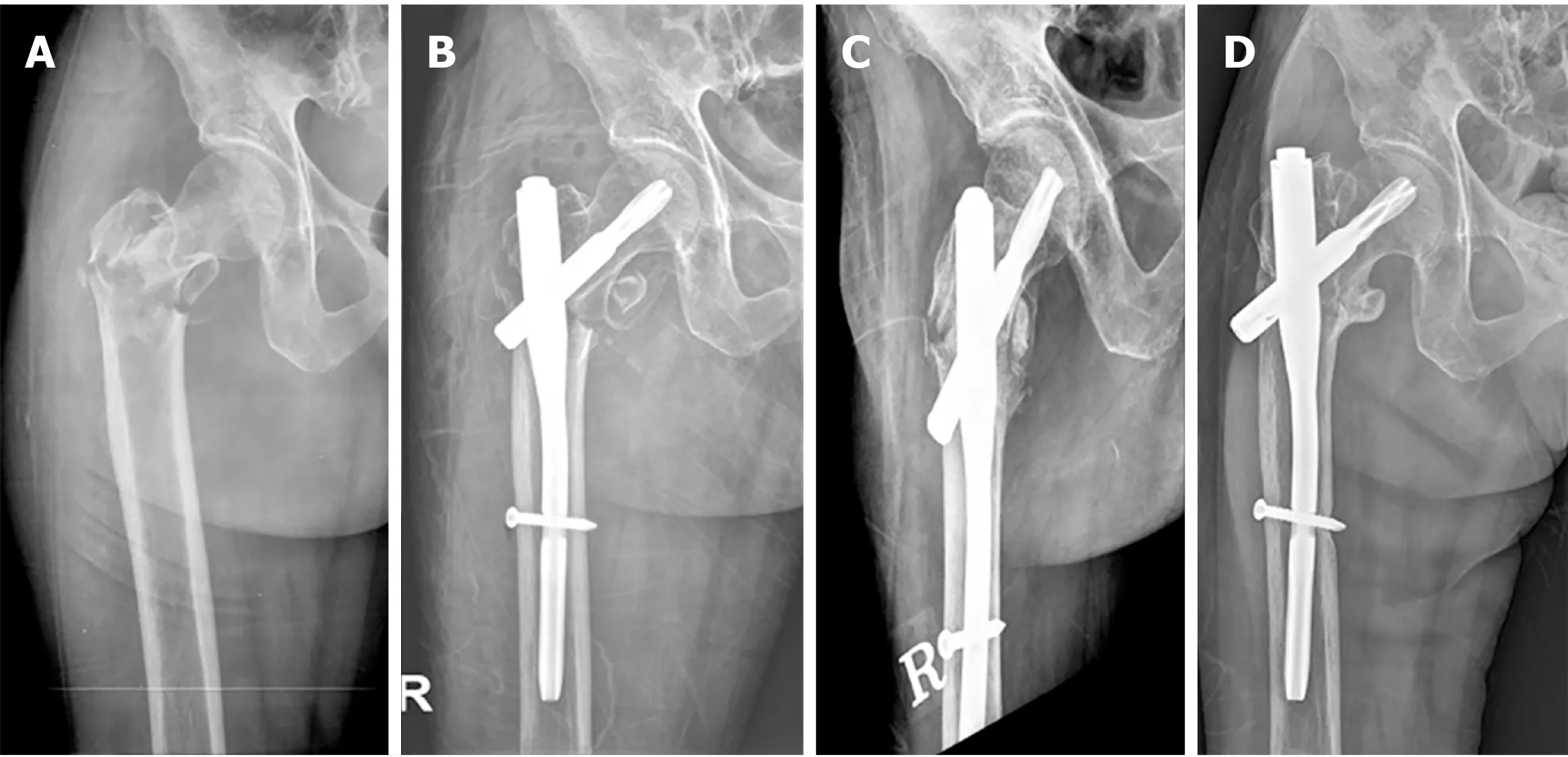

Sliding distance was 6.1 mm (range, 0-23.6 mm) in the PFN group, whereas it was 3.2 mm (range, 0-18.4 mm) in the PFNA group at final follow-up compared to radiographs taken immediately after the index operation. The sliding difference was significantly higher in the PFN group (P= 0.036). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of reduction state, Cleveland Index, TAD, union rate and time to union (Figures 1 and 2).

Table 1 Demographic details and fracture characteristics in the proximal femoral nail and proximal femoral nail antirotation groups

Table 2 Clinical outcomes in the proximal femoral nail and proximal femoral nail antirotation groups

Complications

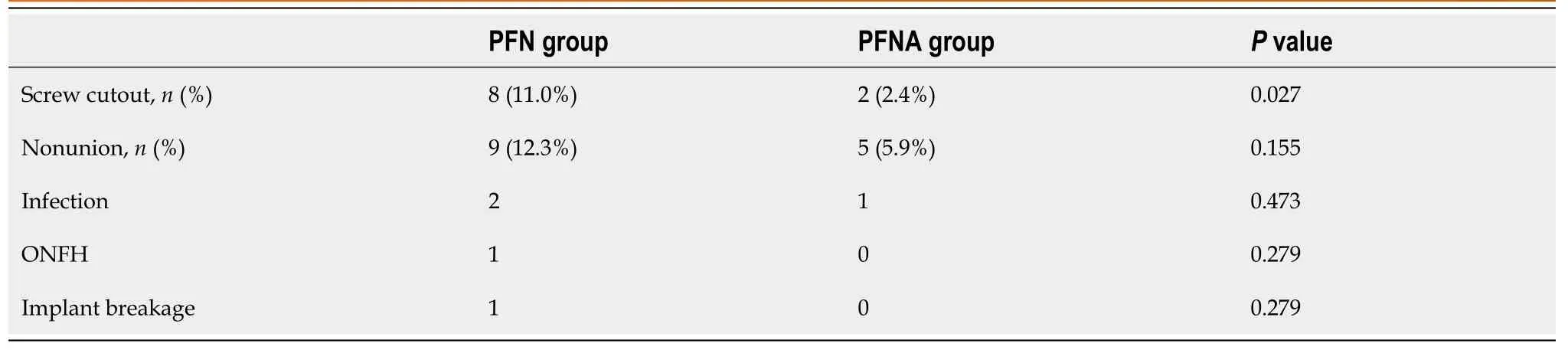

Screw cutout was demonstrated in eight (11.0%) patients in the PFN group and in two (2.4%) patients in the PFNA group (P= 0.027; Table 4). However, there was no statistical difference between groups in terms of nonunion, infection, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, or implant breakage.

DISCUSSION

Among the various implants used for treating proximal femur fracture, PFNA has been developed to overcome several problems of PFN, which has a similar design but uses a helical blade[8,11,12]. According to one biomechanical study, better clinical outcomes might be expected in patients undergoing PFNA than in those receiving the previous-generation PFN[13]. However, few studies have compared the clinical and radiographic outcomes, including cutout after fixation, between PFNA and PFN in elderly patients with PFF. Thus, we performed the current study. Our results indicate that PFNA is associated with better clinical outcomes and fewer complications (in terms of sliding distance and screw cutout) compared to PFN.

Table 3 Radiographic results in the proximal femoral nail and proximal femoral nail antirotation groups

Table 4 Complications in both groups

In our study, the group that underwent PFNA with a helical blade demonstrated less sliding distance compared to the group undergoing PFN with a conventional screw. This result is comparable with previous studies conducted in the laboratory setting, which demonstrated increased resistance of the blade to implant migration, and an increase in interlocking stability[13,20,21]. In a clinical study comparing the sliding distance between PFN and PFNA groups, Chooet al[22]reported that the sliding distance was shorter in the PFNA group than in the PFN group, which was consistent with our results.

Figure 1 Radiographic results.

Figure 2 Radiographic results.

Similar to our study, several studies comparing PFN and PFNA indicated that the PFN group had more implant-related complications[23-25]. We speculate that this result is due to the biomechanical properties of the helical blade of PFNA[13]. As reaming is not performed before blade insertion, the bone stock of the femoral head can be preserved, thereby increasing the contact area between the implant and cancellous bone of the femoral head. In addition, when the blade is inserted, the cancellous bone is compressed, which increases resistance to rotational stress and varus collapse[26]. However, Mallyaet al[27]described that there was no difference in implant-related complications between the two groups. We presume that their study was conducted with a short follow-up period of 6 mo; thus, there was no difference between the two groups.

In the present study, the clinical score after surgery was significantly higher in the PFNA group than in the PFN group (P= 0.033). This result is different to previous studies that reported no difference in clinical outcomes between the two groups[22,25,27,28]. We speculate that the decrease in blade sliding had a smaller effect on native hip biomechanics, including offset and limb length, leading to less reduction in walking ability. In addition, decreased sliding might have resulted in less irritation of the iliotibial band and gluteal sling by the blade itself, leading to less pain.

Our study showed no difference in surgical time between the two groups. In contrast to our findings, several studies[22,24,27,28]reported a shortened time of operation with PFNA when compared with PFN due to the simplified surgical steps. We estimated that this discrepancy among studies might originate from the learning curve associated with the initial introduction of PFNA, which could affect operation time.

The current study is limited by its nonrandomized, retrospective nature, as well as the fact that there were no selection criteria applied for each implant. However, the analysis of demographic characteristics and data related to the operation in the two groups did not reveal any confounding factors such as selection bias. Second, our findings cannot reflect long-term clinical outcomes because of the relatively short-term follow-up. However, a high mortality rate within 5 years has been reported in the literature[29]. Lastly, the current study included a relatively small number of patients, which can weaken statistical power. Nevertheless, we believe that our findings are important as when a theoretically improved implant is introduced, comparison with previous implants of a similar design is paramount to determine the value of the new implant.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, PFNA using a helical blade demonstrated better clinical and radiographic outcomes in terms of clinical score, cutout, and sliding distance following treatment of PFF in elderly patients. However, a randomized study with longer-term follow-up may be necessary to draw a definitive conclusion.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

There are few studies comparing clinical and radiologic outcomes between proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) and previous-generation proximal femoral nail (PFN)in elderly patients with pertrochanteric femoral fracture (PFF).

Research motivation

We evaluated the clinical and radiographic outcomes after fixation with PFN and PFNA for PFF in elderly patients.

Research objectives

From January 2003 to December 2009, seventy-three patients underwent fixation with PFN (PFN group), whereas 85 patients were fixed with PFNA (PFNA group). The mean duration of radiographic follow-up was 2.4 years (range, 1-7 years). The PFN group was composed of 31 men and 42 women with an average age of 76.6 ± 7.3 years.The PFNA group consisted of 37 men and 48 women with an average age of 74.9 ± 7.2 years.

Research methods

We evaluated each patient’s medical history and converted it to a Charlson Comorbidity Index score and femoral bone mineral density. There was no difference in demographics between the two groups (P > 0.05). Clinical outcome was measured in terms of operation time, postoperative function according to Salvati and Wilson’s hip function rating system and mortality rate within one year. Radiographic evaluation included the reduction state after the operation, the Cleveland Index[19], tipapex distance (TAD), union rate, time to union and sliding distance of the screw or blade. Complications, including nonunion, screw cutout, infection, osteonecrosis of the femoral head, and implant breakage were also investigated.

Research results

The proportion of patients with excellent or good postoperative function was significantly higher in the PFNA group compared to the PFN group (94.1% and 83.6%,respectively, P = 0.033). Differences in operation time and mortality within one year were not significantly different between the two groups (P > 0.05). Sliding distance was 6.1 mm (range, 0-23.6 mm) in the PFN group, and was 3.2 mm (range, 0-18.4 mm)in the PFNA group at final follow-up (P = 0.036). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of reduction state, Cleveland Index, TAD, union rate and time to union. Screw cutout was demonstrated in eight (11.0%) patients in the PFN group and in two (2.4%) patients in the PFNA group (P = 0.027).

Research conclusions

PFNA using a helical blade demonstrated better outcomes in terms of clinical score, sliding distance and cutout rate following treatment of PFF in elderly patients than PFN.

Research perspectives

A randomized control study with longer-term follow-up may be necessary to draw a definitive conclusion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Won Kee Lee, PhD for his valuable guidance in the statistical analysis of data, and interpretation of results.

World Journal of Orthopedics2020年11期

World Journal of Orthopedics2020年11期

- World Journal of Orthopedics的其它文章

- Use of short stems in revision of standard femoral stem: A case report

- Modified surgical treatment for a patient with neurofibromatosis scoliosis: A case report

- Treatment of a rotator cuff tear combined with iatrogenic glenoid fracture and shoulder instability: A rare case report

- Müller-Weiss disease: Four case reports

- Proximal fibular osteotomy: Systematic review on its outcomes

- Patients’ perspectives on the conventional synthetic cast vs a newly developed open cast for ankle sprains