Current management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the obese population - a review of the literature

Fermin M. Fontan, Rory S. Carroll, Dakota Thompson, Ryan K. Lehmann, Jessica K. Smith, Peter N.Nau

University of Iowa Hospital and Clinics, Department of Minimally Invasive, Bariatric and Gastrointestinal Surgery, Iowa City,IA 52242-1086, USA.

#Co-equal first authors.

Abstract The current obesity pandemic has a clear impact on quality of life and health resource utilization; hence it has become a significant global health concern. Multiple obesity-related comorbidities such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are frequently observed among this patient population. GERD is a complex disease with multiple elements contributing to the failure of the anti-reflux barrier. If left untreated, the excessive reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus can give rise to multiple complications such as esophagitis, strictures, metaplasia,and cancer. When surgical treatment of GERD is indicated in an obese patient, adequate preoperative evaluation and treatment are critical to achieve durable resolution of symptoms attributed to GERD as well as other obesity related comorbidities. To maximize the potential for a positive outcome, when suitable, gastric bypass surgery rather than sleeve gastrectomy or fundoplication should be strongly considered in the obese patient with GERD.

Keywords: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease, bariatric surgery, RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, SG, sleeve gastrectomy, fundoplication, BE, Barrett’s esophagus

INTRODUCTION

The obesity pandemic has become a significant global health problem. Since 1975, the world prevalence of obesity has nearly tripled, and at least 650 million adults currently have a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

The United States is among the countries with the highest rates: more than 30% of adults are currently obese, with rates up to 40% in some regions of the country[1,2]. Multiple comorbidities have been associated with obesity, and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common. Interestingly, the incidence of GERD in the United States general population oscillates around 15%, whereas among obese patients it ranges from 22% to 70%[3,4].

METHODS

A PubMed search was carried out to identify relevant references to include in this literature review. Two senior surgeons, among the authors of this manuscript, reviewed and selected the references among a vast list of available titles.

GERD definition

In 2006, an international group composed of experts in the field of reflux disease achieved consensus on definitions and classifications regarding GERD. Their aim was to establish a universally accepted terminology that could bridge cultures and simplify management, and to initiate collaborative research studies to assist physicians, patients, and regulatory agencies[5]. GERD was defined as a digestive disorder secondary to persistent gastric contents rising into the esophagus, which can result in a constellation of symptoms and/or complications from chronic acidic exposure. Evidence of troublesome mild symptoms occurring two or more days a week, or moderate/severe symptoms occurring more than once per week were defined as characteristic presentations that could serve for diagnosis.

GERD symptoms can be divided into two categories: typical and atypical. Heartburn, regurgitation,and dysphagia are known as typical symptoms, whereas chest pain, globus sensation, belching, nausea,wheezing, cough, and hoarseness are considered atypical symptoms[6].

Of note, up to 70% of patients with heartburn symptoms have normal endoscopy. Of those, 50% have abnormal pH tests and thus belong to the non-erosive reflux disease group of patients. The remaining 50% can be divided into functional heartburn and reflux hypersensitivity[7]. These functional esophageal disorders are characterized by the presence of chronic typical heartburn symptoms attributed to the esophagus without evidence of inflammatory, anatomic, motor, or metabolic disorders as the underlying etiology. Together, these presentations account for 90% of the heartburn patients who fail proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy at optimal doses[8]. It is important to identify this subset of patients, as the usual management of these conditions differs from classic heartburn patients. The current approach to these patients begins with assurance about the nature of their disorder, followed by neuromodulators which are the cornerstone of therapy[9].

GERD pathophysiology

There are many elements that contribute to the anatomic anti-reflux barriers. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES), the angle of His, the crural diaphragm, phreno-esophageal ligament, and the gastric sling fibers are some of the key components. LES structure and length, anatomic position (including a fundamental intrabdominal portion), innervation, and hormonal control all contribute to its normal function. The LES is not an annular sphincter, but rather formed by two muscle fiber bundles, which have synergistic actions: the “clasp” and the “oblique” muscular fibers. These muscular bundles of approximately 3-cm width cover an area that starts 1.5 cm above the angle of His and ascends to form part of the distal end of the esophagus. These gastric sling fibers form a natural wrap with two arms that extend downwards by running parallel to the lesser curvature[10,11]. Excitatory and inhibitory neurons affect local sphincter tone by regulating the duration and frequency of transient LES relaxations, thereby facilitating intermittent passage of food into the stomach while preventing reflux back into the esophagus[12]. The crural diaphragm,which forms the esophageal hiatus and encircles the proximal LES, in addition to the angle of His, helps to augment this anatomic region. Moreover, the phreno-esophageal ligament anchors the distal esophagus to the crural diaphragm, preventing excessive sliding during respiratory cycles[13].

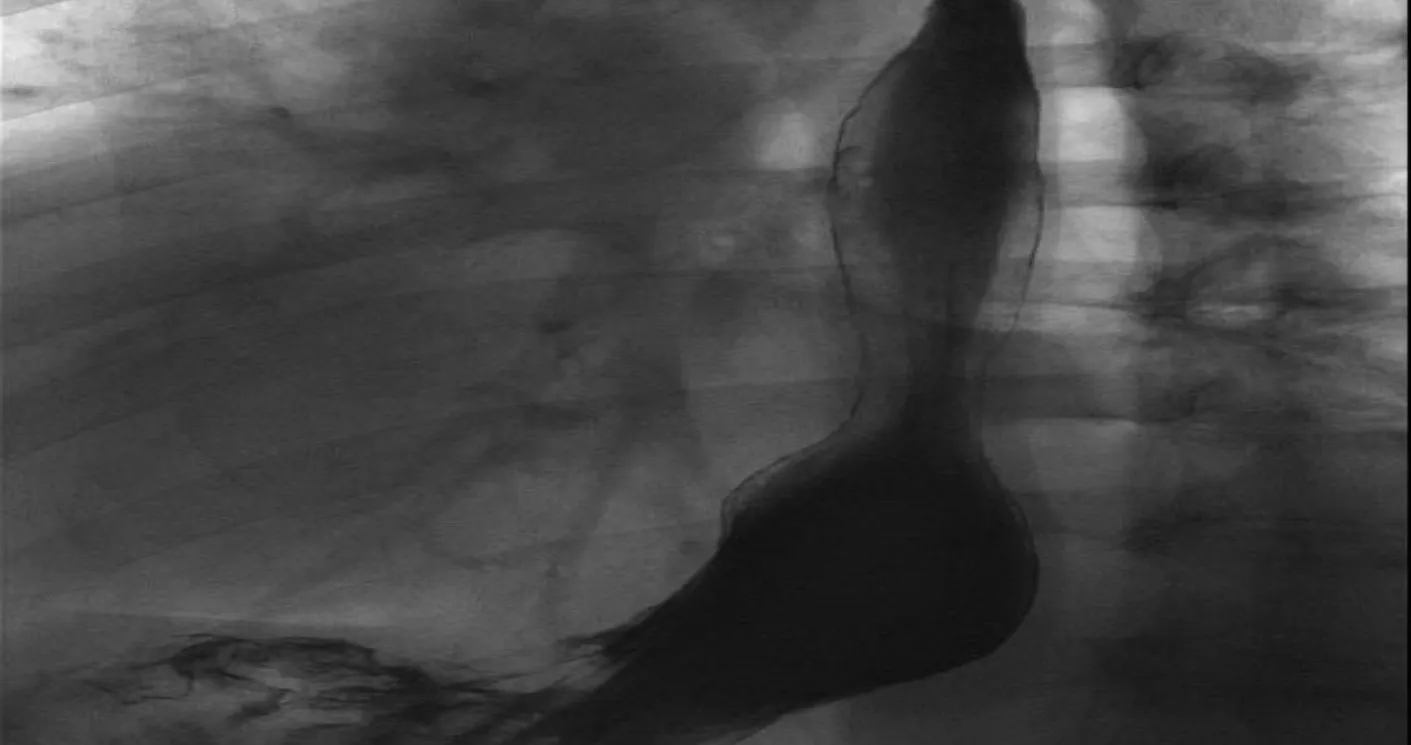

Figure 1. Esophagram showing a hiatal hemia

The development of GERD is usually multifactorial. A failure of the anti-reflux barrier that comprises the LES and the crural muscles of the hiatus are common factors in the pathophysiology. Curiously, in a cohort that included 1659 patients with foregut symptoms, Ayaziet al.[14]was able to demonstrate that the presence of a mechanically defective LES, as well as concomitant hiatal hernias [Figure 1], became more prevalent as BMI increased. Indirectly, LES function can be affected by extrinsic variables. Obese patients’ susceptibility to develop GERD is intimately related to these indirect variables, which include higher gastric capacity(higher distensibility and disruption of muscle fibers), increased intra-gastric pressure, and augmented positive intra-abdominal pressure as well as negative intra-thoracic pressure[15-17]. Herbellaet al.[18]found that for each five-point increment in an obese patient’s BMI, the DeMeester score was expected to increase by three units. Furthermore, from a hormonal standpoint, irregularities in the secretion of adiponectin and leptin from adipose tissue cells has been proposed as a potential nexus between obesity and esophageal metaplasia[4,19].

GERD complications

GERD complications are related to excessive reflux of acid and pepsin, which can result in necrosis of the mucosa. The amount of injury occasionally outweighs the remodeling capacity of the cellular lining,leading to erosions and ulcers, a condition which is defined as erosive esophagitis. A potential complication seen in GERD patients with esophagitis is the development of peptic strictures. These strictures can occur secondary to persistent injury. Scar tissue forms due to chronic necrosis and inflammation, leading to variable degrees of physiologic contraction of collagen fibers. This phenomenon can cause significant narrowing of the esophageal lumen at the esophago-gastric outlet. This type of benign stricture is usually short segment, circumferential, and amenable to therapeutic dilations for patency restoration. Fortunately,the incidence of strictures has significantly declined since the beginning of the PPI era[20].

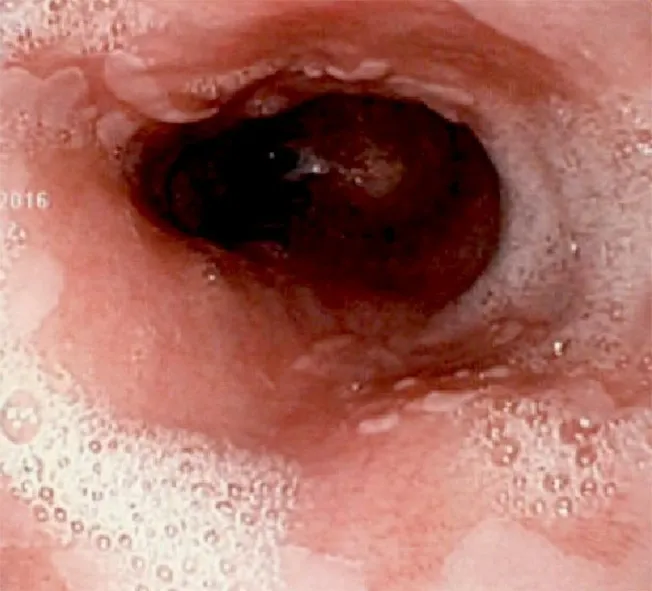

Certain patients can progress to develop metaplastic columnar epithelium which replaces the stratified squamous epithelium that normally lines the distal esophagus [Figure 2]. This is defined as Barrett’s esophagus (BE), and the endoscopic prevalence of this phenomenon in the general population is between 0.5% and 2%. For patients with underlying GERD, the prevalence rises to as high as 15%[21]. In fact, erosive esophagitis is considered an independent risk factor for BE, conferring a fivefold increased risk in a fiveyear follow-up period[22]. Not surprisingly, the prevalence of BE in the obese population can be as high as 40%. These alarming rates are some of the reasons why current trends favor aggressive preoperative screening in bariatric surgery patients[23-25]. This patient population is at higher risk of dysplasia and potential development of esophageal adenocarcinoma, as the risk of cancer in BE patients is estimated to be 30-125-fold greater than that of the general population[26].

Figure 2. Endoscopy showing changes consistent with Barrett’s esophagus

To date, neither medical nor surgical treatment seems to guarantee histologic regression of BE. Multiple authors have shown that surgical management results tend to indicate slightly higher resolution and regression rates when compared to medical therapy arms, but these studies lack statistical power, have highly heterogeneous cohorts, and use relatively short surveillance periods[27-29]. Some authors claim that the main advantage of surgery over medical therapy is that surgery also prevents bile reflux, while proton pump inhibitors control only acid reflux. Other groups have recommended medical treatment because of the less aggressive nature of these therapies when compared to surgery[30-32]. Regardless, interest in regression of BE with antireflux therapyvs.medical therapy has waned in recent years with the rising use of endoscopic ablative techniques such as radiofrequency ablation, which can eradicate the metaplastic mucosa directly[33].

Regarding the effects of bariatric surgery on BE, a meta-analysis of eight studies that included 117 patients with BE undergoing roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) found that 56% of these patients had regression of their BE aたer > 1 year of follow up[34]. Regression rates of short segment and long segment BE were similar in this study. There have only been a few studies looking at the relationship between BE and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). Braghettoet al.[35]reported that, in the short term, 1.2% of their post-LSG patients developed BE. However, in this study, patients did not continue endoscopic surveillance past one year if they were asymptomatic. In a study of 110 patients from a single institution in Italy, 17.2% developed a new diagnosis of BE after LSG at a median follow up of 58 months[36]. The postoperative incidence of GERD symptoms and daily PPI use were also significantly increased. Interestingly, of the patients who had developed BE, 26% had no symptoms of GERD. This finding was also reported in a study by Soricelliet al.[37], in which 21% of post-LSG patients with BE were asymptomatic. Similar rates of “de novo”BE aたer LSG were reported recently (2019)[38]. In a multicenter study, 18.8% of patients had developed BE aたer LSG, with follow up of at least five years. In a study where patients had 10 years of follow up, 15% had developed BE[39]. Although the malignant transformation potential of BE in post-LSG patients is unknown,the authors of the aforementioned studies have proposed endoscopic screening and surveillance, even in patients without GERD symptoms[36-39].

DIAGNOSIS

According to current standards of care, for low risk patients with symptoms and history consistent with uncomplicated GERD, empirical therapy with proton pump inhibitors and lifestyle modifications can be safely offered as an initial approach. On the other hand, for high risk patients with chronic GERD (i.e.,Caucasians, males, those greater than 50 years of age, the obese, smokers, and heavy alcohol users), as well as subjects with complications or who fail to respond to conventional medical therapy, further diagnostic testing should be offered[40].

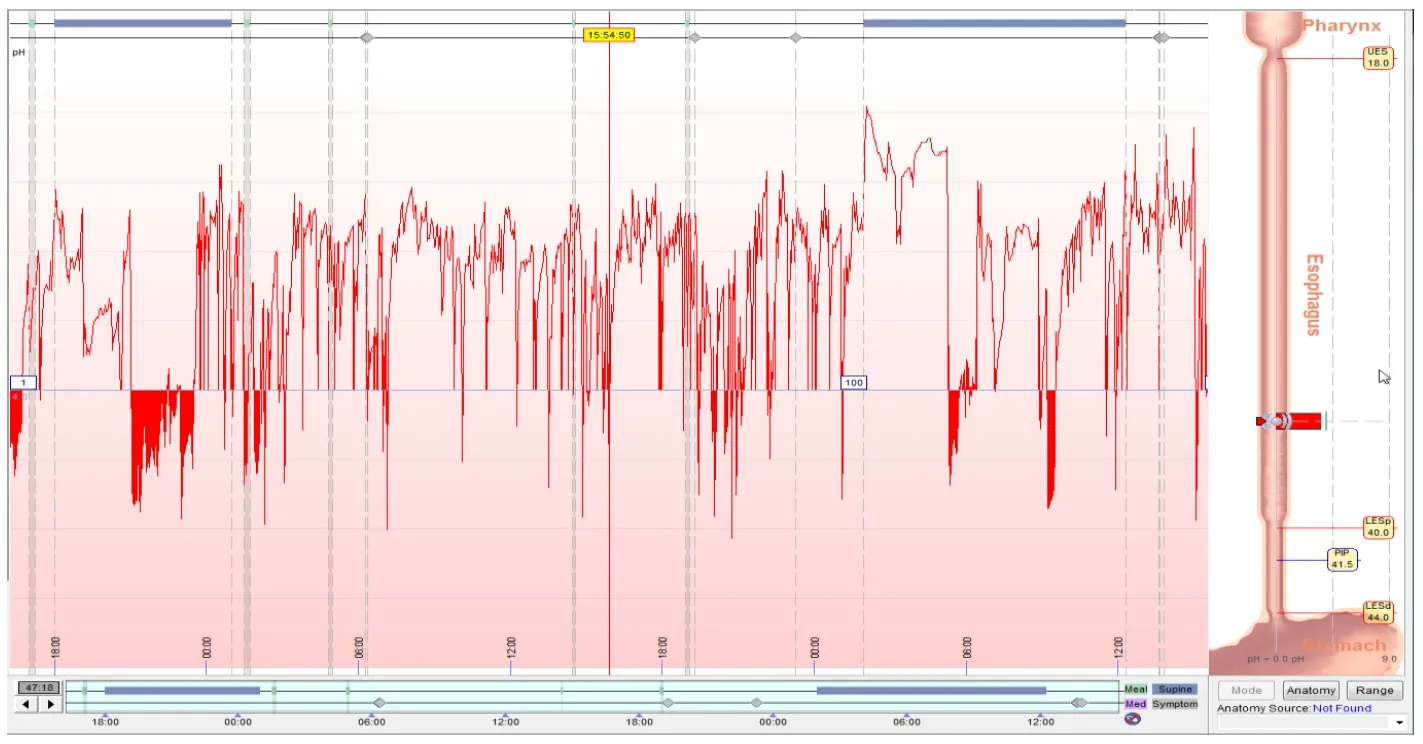

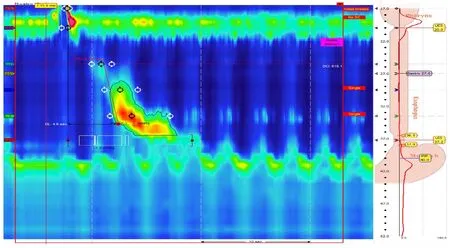

Figure 3. pH Bravo testing showing pathologic reflux

The classic approach for an objective diagnosis of GERD should involve an esophagram, endoscopy, pH testing, and adjunct motility interrogation via manometry. The barium swallow is a cost-effective, noninvasive technique that offers a global examination of anatomy, swallowing function, motility, and can test for gastro-esophageal reflux. The dynamic images obtained through fluoroscopy serve as a guide for decisions about medical, endoscopic, and surgical management[41]. Endoscopy can serve as a diagnostic and therapeutic option. This tool facilitates macroscopic evaluation and permits acquisition of specimens for microscopic assessment of esophageal, gastric, and small bowel disease. It can also aid in the management of different pathologies via dilation, plication, ablation, coagulation,etc.The gold standard in GERD diagnosis is pH testing. Reflux monitoring allows direct measurement of esophageal acid exposure,frequency, and association with symptoms. A composite pH score or DeMeester score greater than 14.72 indicates pathologic reflux. Reflux monitoring is typically performed using either a wireless capsule or a transnasal catheter (pH alone or combined pH-impedance) with the patient ideally off acid suppression therapy [Figure 3]. Lastly, manometry is most useful for the evaluation of esophageal dysmotility and has only limited utility in the presence of hiatal hernias [Figure 4]. Its role in an anti-reflux surgery work-up is to rule out motility abnormalities that would change the decision making as to which type of operation or wrap should be used for fundoplication. This is perhaps most important in those who present with dysphagia as one of their primary symptoms. The mean delay in diagnosis of achalasia is five years and, as reported by Howardet al.[42], 36.8% of achalasia patients are commonly initially treated for GERD. Even though achalasia and GERD are on opposite ends of the spectrum of LES dysfunction, heartburn and regurgitation are frequently seen in patients who have achalasia[42-44].

ANTI-REFLUX SURGERY, LSG, AND LAPAROSCOPIC ROUX-EN-Y GASTRIC BYPASS

Surgical therapy for GERD has been shown to be equally effective as medical management, with comparable quality of life scores[45]. Anti-reflux surgery is considered in patients who have failed medical management, have extra-esophageal manifestations, have complications of GERD, or have a personal preference or medical reason to avoid life-long PPI use. The gold standard laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and the more recent Linx procedure have been shown to be very successful and equally effective in multiple studies[46,47]. The literature shows rates of symptomatic recurrence of heartburn less than or equal to 10%, improvement in regurgitation higher than 85%, and long-term satisfaction rates over 90%[45]. These numbers reflect outcomes in the general population. However, when patients are stratified and segregated by their BMI, results are not as favorable.

Figure 4. High resolution manometry showing a hiatal hernia and abnormal contraction propagation

The long-term durability of anti-reflux procedures in obese patients is a topic of controversy. The lack of definitive consensus is in part related to the fact that most of the studies available lack statistical power, fail to adequately represent morbidly obese patients, and, most importantly, have limited information on longterm outcomes. The preponderance of the data suggests that durability and efficacy is decreased in obesity[Table 1]. Perezet al.[48]noted an overall symptomatic recurrence rate of 31.3% in obese patients who underwent Nissen or transthoracic Belsey Mark IV fundoplication compared to 4% in normal-weight patients.In a study conducted to determine risk factors for failure of anti-reflux surgery, Morgenthalet al.[49]identified a BMI greater than 35 as a significant risk factor for failure. Interestingly, in an obese cohort undergoing salvage gastric bypass aたer a failed fundoplication, the incidence of wrap disruption appeared to be higher than the rate of an intact herniated wrap. This observation suggests that the mechanism of failure in obese patients may be different than in the non-obese population[50].

When compared to Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB), the rates of LSG have increased over the last decade. It is now the most commonly performed weight-loss metabolic surgery in the world[51].LSG has become popular among surgeons due to its relatively simple technique, lack of anastomoses and fewer potential associated complications. This is problematic, secondary to the significant correlation between obesity and GERD as well as the ill-defined role that the LSG has in the treatment of this cohort.Currently, there is no consensus on the management of GERD in the obese population as it relates to which operation is best, but the data suggest that the RYGB is a superior operation when considering GERD-related outcomes. This is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that postoperative GERD was the most frequently reported complication among surgeons surveyed at the Fourth International Consensus Summit on Sleeve Gastrectomy[52]. In a review paper drafted by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons Foregut Task Force, the LRYGB was identified as the treatment of choice for GERD in obese patients. Authors such as Frezzaet al.[53]showed significant improvement of GERD symptoms aたer offering LRYGB. His cohort of 152 obese patients with GERD had a substantial decrease in the use of antiacid medication by 6 months aたer surgery. Along these lines, De Groote’s systematic review of bariatric surgery and GERD compared various bariatric procedures and found that LRYGB was associated with a notable decrease in GERD. They also analyzed outcomes of the LRYGB compared to lifestyle modifications only, and the former group had better alleviation of GERD symptoms[54-56].

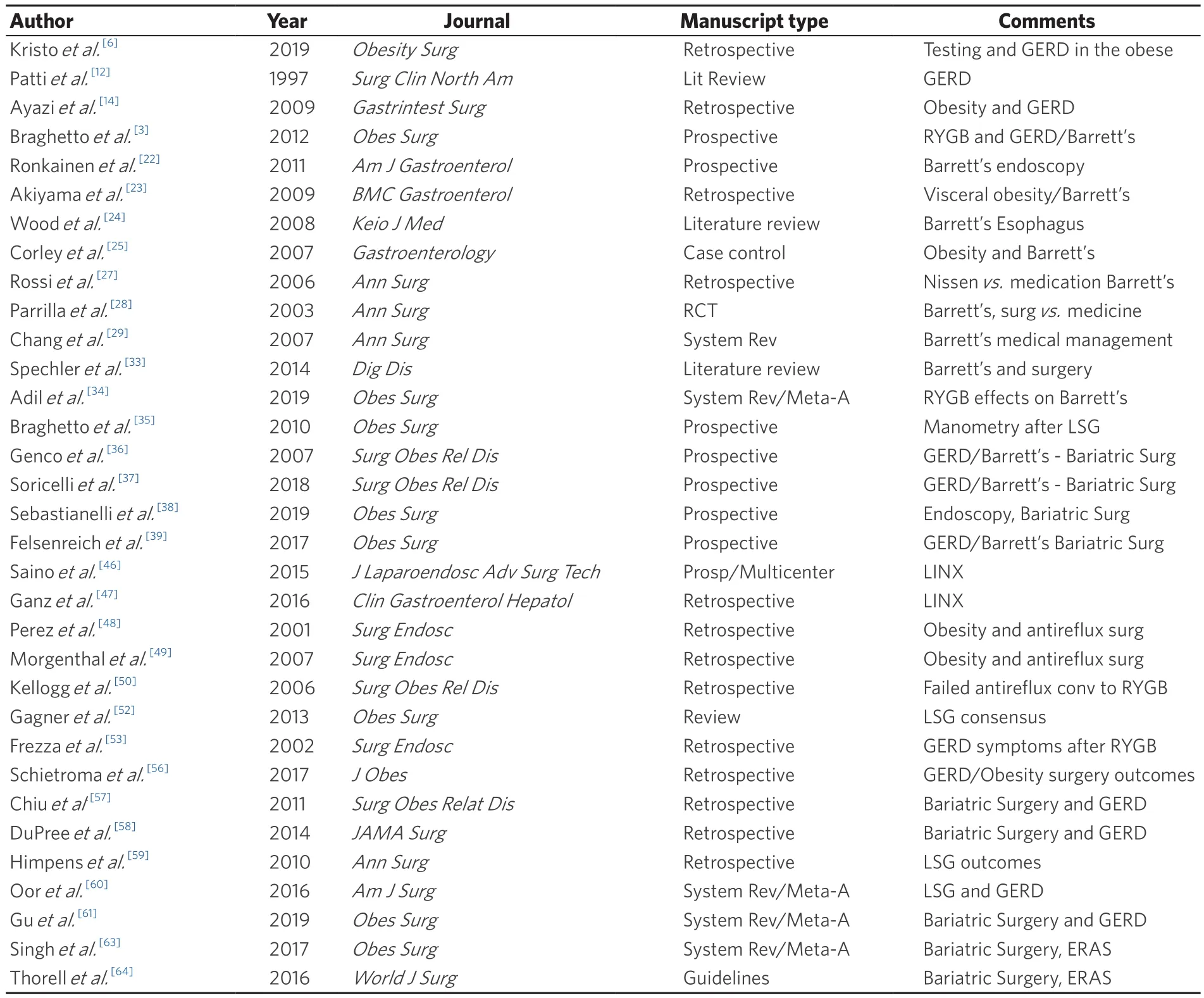

Table 1. Most relevant manuscripts organized by topic

In contrast to the outcomes seen aたer LRYGB in GERD patients, there are conflicting data surrounding the relationship between GERD and LSG. In 2011, a systematic review of studies reporting post-LSG GERD rates found no agreement was achieved[57]. Seven of the studies that were included showed reduced prevalence of GERD after LSG, while four found an increase in GERD. An important limitation of many of these publications is the use of subjective symptoms to confer a diagnosis of GERD rather than objective diagnostic exams. Furthermore, different follow up times and definitions of GERD among these studies made it difficult to make conclusions. In a retrospective review including 4832 bariatric surgery patients, 70% of patients with preop GERD had no resolution of symptoms aたer LSG, with 8.6% of patients developing de novo GERD aたer 3 years[58]. In another study with six years of follow up aたer LSG, 23% of patients had GERD compared to 3.6% prior to surgery[59]. However, in a systematic review that included 33 articles with 8092 post-LSG patients, the authors concluded that there was a trend in increased GERD prevalence following LSG, but no definitive conclusions were attained due to the high heterogeneity of the studies[60]. In another study which included 3534 obese patients, the occurrence of de novo GERD was 9.3% aたer LSG and 2.3% aたer LRYGB. Overall, 40.4% of patients who had undergone LSG eventually showed improvement or remission of GERD, compared to 74.2% of patients in the LRYGB group. The pooled analysis showed that, compared with LSG, LRYGB had a better effect on GERD[61]. It is impossible to concretely state the risk of GERD following LSG due to the lack of well-designed studies and adequate long-term follow up. Notwithstanding this fact, the data do advocate for the superiority of the RYGB when compared with the LSG in the care of a population with concomitant GERD and obesity.

One of the contributing factors to the difficulty of treating this population is the lack of a consensus on the appropriate preoperative evaluation of the anatomy and function of the foregut prior to a weight loss and metabolic operation. Some authors have advocated for the routine use of EGD and esophagrams,while others have stated that these are not necessary. Many of these papers were published before the LSG era when RYGB and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band were the principal operations offered. With this in mind, Kavanaghet al.[62]protocolized patients with subjective GERD symptoms to undergo preop workup including esophagram and EGD. In the cases where the patient desired LSG, further assessment with esophageal pH testing and high-resolution manometry were ordered. Interestingly, they showed that pathology was commonly found on testing; based on protocol test results, 24.8% of their patients had a change in the procedure selected. Kavanaghet al.[62]set a perfect example of the current trajectory in patient care within the bariatric surgery field. Despite excellent results with the available standardized pathways such as “Enhanced Recovery After Bariatric Surgery”, the field is moving toward offering each patient individualized care based on their comorbidities, functional status, and risk-benefit from surgery[63-65]. Different calculators can assist surgeons to select the most suitable surgery in order to ensure the best possible outcome. For example, the individualized metabolic surgery score calculator has been proposed for procedure selection based on diabetes severity[66]. It is used to differentiate patients who have higher odds of improvement/resolution of their diabetes based on disease severity and type of operation.Another example is set by the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program risk-benefit calculator[67]. This tool helps to guide surgical decision-making and informed consent. By implementing 20 patient predictors, this calculator offers information on the likelihood that patients will experience common morbidities and can forecast weight loss and comorbidity resolution.Whether addressing the chance to cure diabetes and GERD or the potential for perioperative morbidity,individualized care based on unique patient characteristics represents the future of surgery in an obese population.

CONCLUSION

Obesity and GERD are both conditions with a significant impact on health-related quality of life and global health resource utilization. The implications of inadequately treated GERD can lead to dangerous complications and need for potentially morbid interventions. There are clear limitations in interpreting the available data due to inconsistency in the definition of GERD. Moreover, the complexity and invasiveness of objective evaluation of GERD can impede its widespread application. However, when surgical treatment of GERD is indicated in an obese patient, adequate preoperative evaluation can maximize the probability of addressing all the patient’s comorbidities. In addition, offering LRYGB rather than LSG or fundoplication should be strongly considered in this patient population in order to maximize the potential for a positive outcome.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Guided the work, decided on content, concepts discussed, overall edition: Nau PN

Made equal contributions regarding writing, design, edition of the entire manuscript, reviewed corrections and resubmitted the work: Fontan FM, Carroll RS

Made substantial contributions mainly focused on manuscripts selected for references and overall edition:Thompson D, Lehmann RK, Smith JK

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

? The Author(s) 2020.

- Mini-invasive Surgery的其它文章

- Cause of recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis following esophageal cancer surgery and preventive surgical technique along the left recurrent laryngeal nerve

- Mediastinoscopic esophagectomy with lymph node dissection using a bilateral transcervical and transhiatal pneumomediastinal approach

- MlS Al - artificial intelligence application in minimally invasive surgery

- From TATA to single port robotic (SPr) taTME:approaches to distal rectal cancer

- Endoscopic-assisted lCG (EASl) technique for sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer

- Uniportal video assisted thoracoscopic left upper bronchial sleeve lobectomy in a pediatric patient