Aging skin and non-surgical procedures: a basic science overview

Amy R. Vandiver, Sara R. Hogan,2

1Division of Dermatology, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA.

2David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA.

Abstract Skin aging is a major cosmetic concern and associated with extensive changes in skin function and structure. The understanding of the basic science underlying skin aging is rapidly progressing, anchored around nine fundamental hallmarks of aging defined in 2013. Here we present the evidence for the relevance of each hallmark of aging to skin aging, emphasizing the uniquely prominent roles of oxidative damage and the extracellular matrix in photoaging. We review the existing evidence for how established treatments of skin aging target each fundamental hallmark and discuss targets for potential future treatments.

Keywords: Aging, photoaging, intrinsic aging, antiaging, rejuvenation

INTRODUCTION

Skin aging is associated with extensive changes in the structure and function of all aspects of the skin and serves as a major risk factor for multiple pathologies including atopy, impaired wound healing, infection and malignancy[1-5]. In addition to functional concerns, the aging of sun-exposed skin, with the face in particular, is a major cosmetic concern prompting patients to seek cosmetic procedures. While therapies to reduce or prevent aging of sun-exposed skin have been present for decades, our understanding of the basic science underlying aging is rapidly evolving, shedding light on the mechanisms of established treatments and identifying new treatment targets and methods. In this article, we will discuss the current understanding of the hallmarks of aging as applied to skin aging, review how current treatments target this underlying biology and discuss future treatments identified by this emerging knowledge.

SKIN AGING

The skin consists of two layers with distinct cell populations and underlying biology. The outermost layer, the epidermis, is a stratified epithelium consisting primarily of keratinocytes. The inner most layer of the epidermis consists of proliferating basal keratinocytes, above which are three differentiated layers: the stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum and stratum corneum. The outermost layer, the stratum corneum consists of anucleate corneocytes in a lipid-rich matrix. The epidermis is regenerated by epidermal stem cells, distinct populations of which are found throughout the basal layer of the epidermis and in the hair follicle[6,7]. Below the basal layer of the epidermis lies the dermis which consists of a collagen-rich extracellular matrix (ECM) supporting vasculature and adnexal structures. This matrix is generated by dermal fibroblasts, terminally differentiated cells of mesenchymal origin.

Aging of sun-exposed skin (photoaging) and sun-protected skin (intrinsic or chronological aging) are distinct processes with both common and unique manifestations and molecular mechanisms. Intrinsic aging is commonly associated with increased xerosis (dry skin), fine rhytids and laxity. Photoaging shares these features but also exhibits uneven pigmentation, deeper rhytids, telangiectasias and increased growth rate of malignant neoplasms. Histologically, photoaging demonstrates uneven thinning of the epidermal layer with thickening of the granular layer and more compact corneal layer, dermal ECM loss of collagen and elastin, as well as increased dermal inflammation[8-11]. Such histologic findings correlate with increased gene expression of matrix metalloproteinases and decreased gene expression of ECM components, particularly collagen and elastin. These changes are seen in multiple models of photoaging, and as such have been used as markers in many mechanistic and therapeutic studies[12-15].

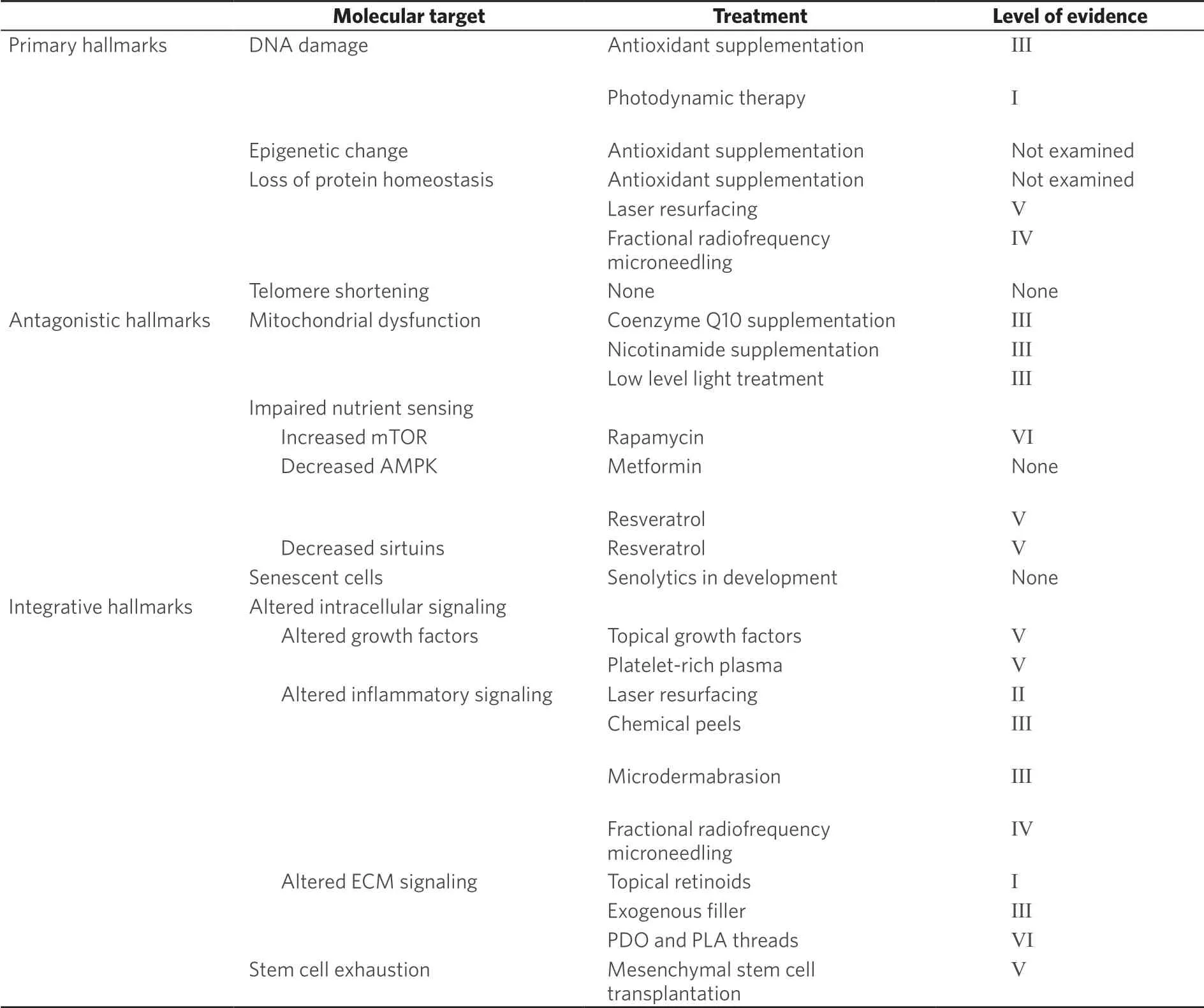

Investigation into the basic biology of aging has steadily grown since the 1980s. Original studies focused on identifying a single driving mechanism. However, in 2013, López-Otínet al.[16]proposed a distinct framework for studying aging biology focused on nine hallmarks of aging, which together contribute to age-related functional change. This marked a shift towards understanding aging not as a single process, but instead as a combination of biological changes. These hallmarks are broken into three categories: primary, antagonistic and integrative [Table 1]. The primary hallmarks of genomic instability, epigenetic change, loss of proteostasis and telomere attrition, are the foundational changes that initiate aging phenotypes. Antagonistic hallmarks occur in response to these alterations and include de-regulation of nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular senescence. Together, these all contribute to the integrative hallmarks - impaired intracellular communication and stem cell exhaustion - which most directly contribute to tissue aging phenotypes.

Since publication, López-Otínet al.[16]’s hallmarks of aging have been widely accepted and used extensively as a framework for aging research. It is increasingly recognized, however, that each tissue and cell population ages in a distinct manner, with differing hallmarks playing a more prominent role for each[17]. While photoaging shares the majority of the hallmarks of aging seen across cell types, we will discuss evidence that the central role of ultraviolet (UV) exposure and prominence of the ECM in aging biology make the damage and signaling associated hallmarks particularly relevant. Below, we will review each of the hallmarks of aging as applied to skin aging and discuss treatment modalities targeting each set of changes.

Primary hallmarks of skin aging

Genomic instability

In photoaging, UV radiation plays a prominent role in inducing the primary hallmarks of aging, particularly genomic instability. UV radiation is linked to DNA damagein vivoand in cell culture. UVB exposure leads to the formation of cyclobutane dimers in the nuclear genome[18]. UVA exposure causes the generation of reactive oxidative species (ROS) and oxidative guanine damage[19]. Upon nucleic acid repair, both of these changes induce cytosine to thymidine nucleic acid sequence alterations, which, depending on location, leads to gene dysregulation. These UV-induced mutations in specific genes are linked to skin cancer and loss-of-cell function[20-23]. UVA exposure also leads to large modifications in the circular mitochondrial genome, which lacks many of the repair mechanisms that maintain the nuclear genome: photoaged skin is repeatedly observed to contain large deletions in the mitochondrial genomein vivo, and UVA directly induces these changes in cell culture[24-27]. Similar mutations are linked to mitochondrial dysfunction in other organ systems[28].

Table 1. Hallmarks of aging

Epigenetic alterations

In addition to the sequence itself, expression of the nuclear genome is very closely regulated by the epigenome through modifications of the nucleotides and proteins involved in DNA packaging[29]. With both intrinsic aging and photoaging, epidermal tissue shows loss of methylation of cytosine bases, with a larger degree of loss in photoaged tissue[30,31]. Compared to sun-protected skin, sun-exposed skin also demonstrates changes in histone modifications, specifically increases in open areas of chromatin that are permissive to gene expression[32]. At least some of these changes are directly linked to UV-induced ROS, which directly trigger de-methylationin vitro[33].The loss of cytosine methylation and increase in histone acetylation are both linked to increased “transcriptional noise”, or low-level transcription of unnecessary genes thought to interfere with cell function in other systems[34,35].

Telomere attrition

The nuclear genome, mitochondrial genome and epigenome are all clearly demonstrated to change in photoaged skin. It is less clear if changes in the length of telomeric end sequences are prominent in skin aging. Decreases in telomere length occur in dividing cells that lack the enzyme telomerase, and this has been shown to occur more with in association with increased levels of ROS in cultured fibroblasts[36]. Such decreases are strongly associated with aging phenotypes in mice[37]. However, the relationship between telomere length and human biological age is less direct[38]. For skin in particular, the relevance of shortened telomere sequences to epidermal and dermal aging phenotypes remains unclear. While some studies have documented significant decrease in telomere length in skin with age[39-41], there appear to be equivalent levels of change in photoaged and intrinsic aged samples. In addition, studies focused on the epidermis suggest telomerase may be expressed in basal keratinocytes and increase with sun exposure and inflammation[42-44], correlating with a low magnitude of telomere length decrease with age[43].

Loss of proteostasis

Beyond the genome, aging is associated with notable loss of regulation of protein homeostasis - or “proteostasis”. In healthy cells, proteostasis is maintained by the proteasome, an enzyme complex that balances new protein synthesis with damaged protein degradation[45].In photoaging, increased levels of ROSin vivolead to dermal accumulation of oxidatively modified and damaged proteins and cellular dysfunction[46].In concert, proteasome components decrease in photoaged and intrinsically aged skin[47,48].

Targeting the primary hallmarks of aging

UV-induced ROS play a clear role in generating many of the primary insults thought to initiate cutaneous aging phenotypes. The endogenous antioxidant system consists of non-enzymatic antioxidants, which acquire electrons to neutralize ROS, and enzymatic antioxidants, which deactivate ROS (A complete discussion of the antioxidant system in skin is available[49]). As such, classic antiaging treatments focus on preventing skin damage by decreasing levels of ROS through topical and oral supplementation of components of this system.

A wide range of endogenous non-enzymatic antioxidants are used in topical antiaging formulations. Examples include vitamin C, vitamin E, niacinamide, lycopene, carotenoids and polyphenols[49]. Resveratrol, a polyphenol, also increases synthesis of glutathione, an endogenous enzymatic antioxidant[50]. In cell culture models, supplementation with vitamin C directly prevents UV-induced DNA damage and increases expression of the proteasome to scavenge damaged proteins and supplementation with niacinamide enhances repair of UV-induced damage[51,52]. Clinically, topical application of vitamins C and E, polyphenols and resveratrol show efficacy in reducing acute UV-induced erythema and DNA damage markers[53-56].

Oral antioxidant formulations are protective against acute UV-induced damage. Oral supplementation with multiple non-enzymatic antioxidants have been demonstrated to decrease UV-induced erythema, inflammatory markers and the incidence of actinic keratoses[57]. Systemic reviews, however, suggest that certain oral antioxidant formulations may be associated with increased mortality, likely given the beneficial role of anappropriatelevel of ROS in many body systems[58].

Still, both topical and oral antioxidant formulations primarily show benefit for preventing - not reversing - photoaging damage. There is evidence that vitamin C supplementationin vitroincreases collagen synthesis and topical combinations result in modest photoaging benefits, but it is not known whether levels of existing damage are altered[59]. Furthermore, while ROS have been directly linked to nuclear and mitochondrial genome impairment, epigenetic change and protein oxidation, no study has demonstrated a reduction of these specific alterations after topical or oral treatment. The exact degree to which these changes are prevented or reversed remains unknown.

Destructive treatments targeting oxidatively damaged cells are shown to have clinical benefit for photoaging. Photodynamic therapy - in which aminolevulinic acid is activated by visible light to destroy rapidly proliferating cells - decreases damaged cells within the epidermis (as noted by p53 expression), promotes collagen synthesis and improves clinical photoaging grade[60]. Energy- and laser-based therapies such as radiofrequency microneedling, fractional non-ablative laser and fractional ablative laser, all induce broad destruction of tissue, including the destruction of cells containing oxidatively damaged DNA and proteins. While the level of oxidative damage post-treatment has not been specifically tested, these treatments are shown to induce the expression of specific heat shock proteins known to promote the clearance of damaged proteins[61-63].

Antagonistic hallmarks of aging in photoaging

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Mitochondria serve as the primary energy-generating powerhouses of the cell. The number, morphology and activity of mitochondria are closely regulated in numerous biological conditions[64]. Possibly related to the accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) alterations as discussed above, there is growing evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction involving altered oxidative phosphorylation in photoaged skin.

In vivoimaging of photoaged epidermis demonstrates a more fragmented mitochondrial network, which may correlate with altered aerobic function[65]. Cultured keratinocytes also show decreased electron transport chain (ETC) activity and thus decreased oxidative phosphorylation and a shift to anaerobic metabolism with photoaging[66]. A direct relationship between mitochondrial dysfunction and skin aging phenotypes is supported by multiple mouse models: in mouse models in which mitochondrial antioxidants or transcription factors are reduced, keratinocyte differentiation is impaired and increased senescence keratinocytes noted[67,68], and in a model in which mtDNA is progressively decreased, dermal atrophy, increased MMP-1 expression and epidermal hyperplasia are noted[69].In vitro,the restoration of ETC activity is shown todecreaseMMP1 expression after UVA radiation, further suggesting a direct link between mitochondrial function and aging phenotypes[66].

Impaired nutrient sensing

Closely linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and aerobic metabolism alteration, there is significant evidence that nutrient sensing is linked to photoaging. Nutrient sensing is the mechanism by which cells recognize and respond to energy substrates. The concept of impaired nutrient sensing stems from genetic evidence suggesting that those gene variants most linked to lifespan occur within pathways involved in sensing nutrient abundance[70]. Models suggest that upregulation of the protein mTOR kinase, which signals nutrient abundance, is associated with aging, and that proteins that signal nutrient scarcity, such as AMPK and sirtuins, are downregulated[71]. In mouse models of photoaging, mTOR components are increased and AMPK is decreased[72,73]. Similarly, sirtuins are noted to be decreased in fibroblasts isolated from both sunexposed and photoaged individuals[74-76]. While these alterations infer that aged skin is signaling a state of nutrient excess, metabolomic profiling of epidermal samples suggests there is downregulation of anabolic biosynthetic pathways and upregulation of catabolic pathways, consistent with an overall impaired function of nutrient sensing[77,78].

Accumulation of senescent cells

Senescent cells are those that have permanently exited the replicative cell cycle, and accumulation of these cells has been observed with the aging of many tissues. Despite stopping replication, they are metabolically active and have a distinct secretory profile known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) which can have profound effects on surrounding cells[79,80]. The induction of senescence is strongly linked to DNA damage as well as epigenetic changes and loss of proteostasis, so it is not surprising that the presence of senescent cells is significantly increased in photoaged epidermis and dermis[81]. In addition, mTOR activity is linked to the induction of senescence in keratinocytes, indicating that the accumulation of senescent cells in photoaged skin is multifactorial[82]. The presence of senescent cells in photoaged skin has been linked to photoaging phenotypes in cell culture models: senescent fibroblasts promote ECM degradation through increased MMP-1 secretion and induce a proinflammatory environment, which can promote ECM degradation and keratinocyte tumorigenesis[79,83]. Also, the introduction of senescent fibroblasts into organotypic skin models induces thinning of the epidermis and decreased barrier function in the overlying epidermis[84].

Targeting the antagonistic hallmarks of aging

Given the evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired nutrient sensing in aging phenotypes, there is a move to target aging treatment and prevention at these deficits, both by improving mitochondrial function and reversing the signals of nutrient abundance. Mitochondrial dysfunction can be mitigatedin vivothrough supplementation with specific antioxidants. Supplementation with coenzyme Q10, which acts as a diffusible electron transporter in the mitochondrial transport chain, is shown to improve mitochondrial function in multiple oxidative systemsin vivo[85,86]and restore oxidative metabolism in aged keratinocytesin vitro[66,87].Nicotinamide, which acts as a precursor of the main oxidative substrate NAD+, is also shown to improve mitochondrial quality and promote keratinocyte regenerative capacityin vitro[88,89].

In addition to working as an antioxidant, resveratrol exerts antiaging effects through benefits to mitochondrial function and modifications in nutrient sensing. Resveratrol promotes oxidative metabolism through multiple pathways.In vivoandin vitro, resveratrol activates the nutrient sensor AMPK and thereby activates sirtuin 1[90-92]to shift cells to a state of nutrient deficiency[93]. Through sirtuin 1, resveratrol directly increases the synthesis of new mitochondria in multiple tissues[94]. While this highlights resveratrol as an appealing option for topical therapy, current small trials of topical formulations have unclear evidence of benefit and the bioavailability of these formulations remains questionable[50,95,96].

Low-level light therapy is promoted to treat photoaging through improving mitochondrial function. This treatment involves exposing target tissue to low levels of red or near infrared light and is rising in popularity as many devices can be used for home treatment[97].In vitrostudies have shown that specific wavelengths of red and near infrared light are absorbed by cytochrome oxidase c, an enzyme involved in the mitochondrial ETC, and that this absorption increases mitochondrial enzyme activity and energy production[98-100]. This increased mitochondrial activity is in turn shown to increase collagen production and growth factor secretion in cultured fibroblasts[101,102], and multiple small trials of low-level light therapy demonstrate modest to moderate benefit for facial rhytids[103,104].

Though not yet available for use on skin, multiple metabolic regulatory molecules studied for systemic antiaging have potential for use as topical therapies. Metformin, developed for use in diabetes mellitus, works as an AMPK activator to alter the cell metabolic profile. In fibroblast culture, metformin stimulates collagen production, and topical formulations promote wound healing and barrier integrity in mouse models[74,105]. Recent advances in topical formulations of metformin that permeate human skin suggest this may emerge as an antiaging treatment option[106]. Similarly, topical formulations of rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor, reduce markers of cutaneous aging in human skin in addition to other aging models[107,108]. Rapamycin was noted, however, to have negative effects on wound healing and thus requires further study before use for antiaging[74].

Another future treatment strategy involves directly targeting senescent cells for removal. Due to their altered signaling profile, senescent cells can theoretically be targeted for destruction via compounds specific to their upregulated components. In transgenic mouse models, the selective apoptosis of cells entering senescence prevents many aging phenotypes but imparts minimal effect on dermal thickness and also delays wound healing[109,110]. Multiple compounds that target molecules upregulated in senescent cells, known as senolytics, including dasatinib, quercetin, navitoclax and piperlongumine show efficacy in clearing senescent fibroblasts and other cell populations in culture; however, none have been reported to have efficacy for skin aging phenotypesin vivoat this time[111-114].

lntegrative hallmarks of aging

Altered intracellular signaling

The end points of the primary and antagonistic hallmarks of aging lead to the integrative hallmarks, specifically impaired intracellular communication and stem cell exhaustion.

The most prominent age-related change in intracellular communication is increased inflammation mediated by NF-kappaB (NF-κB), which leads to upregulation of IL-1B, tumor necrosis factor and interferon signaling, and overall decline in adaptive immune function[16]. In the epidermis, increased NF-κB signaling is inducible by UV exposure and promotes epidermal stem cell dysfunction[82,115]. When NF-κB is inhibited in mouse models, intrinsic aging phenotypes are reversed[116]. In addition, photoaged skin also exhibits decreases in other cytokines, such as TGF-B and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), which promote collagen synthesis and epidermal regeneration[117].

In photoaging, the ECM plays a uniquely important role in mediating intracellular signaling. Photoaging is strongly associated with the degradation of collagen in the dermal ECM. This change is initiated by UVinduced increase in MMP secretion by basal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts, and is associated with the activation of AP-1 signaling[13]. Once degraded, collagen is present within the matrix, andin vitrostudies suggest this amplifies intracellular aging. Dermal fibroblasts grown on synthetically-degraded collagen generate increased ROS, increased MMP secretion, and decreased collagen production[13]. MMP expression in co-culture fibroblasts also decreases the regenerative capacity and longevity of epidermal stem cells[118].

Stem cell exhaustion

The final integrative hallmark of aging is stem cell exhaustion, which has a notable role in the epidermal photoaging phenotypes. Two distinct stem cell populations - epidermal and hair follicle stem cells - are thought to maintain the epidermis in different biological settings[6,7]. While decreased regeneration and epidermal thinning is noted with both murine and human aging, the specific changes to these stem cell populations is complex and continues to be investigated.In vivo, multiple studies have demonstrated consistent or increased numbers of stem cells in intrinsically aged human and mouse skin[119-121]; however, other studies have demonstrated decreased stem cell functional markers in intrinsically aged and photoaged skin, possibly partially linked to UV-induced basement membrane changes[122-124]. In photoaging, this is likely directly linked to many of the previously discussed UV-induced hallmarks, including the DNA-damage response, increased NF-kB signaling, metabolic dysregulation through mTOR upregulation, senescence and ECM degradation, emphasizing the inter-related nature of all aging hallmarks in cutaneous photoaging[82,114,116,118,121,125]

Targeting altered intracellular signaling and stem cell exhaustion

As evidence grows of photoaging-induced impairment in signaling molecules, various approaches have been tested to reverse this change. Researchers have attempted to directly supplement certain growth factors that decline with age. Multiple small trials show clinical benefit with topical formulations of growth factors and cytokines, including TGF-beta, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), FGF, IL-1 and TNFalpha, in reducing fine lines and wrinkles and increasing dermal collagen[126-128]. The true efficacy of these topicals, however, is questionable. Growth factors and cytokines are large, hydrophilic molecules with greater than 15,000 Da molecular weight, and prior studies demonstrate that hydrophilic molecules greater than 500 Da have low penetration past the stratum corneum[129].

Treatments that directly target ECM degradation and associated signaling amplification alteration are more effective. Topical retinoids are well established as clinically effective treatments for photoaging. Retinoids decrease AP-1 and NF-kB signaling and increase TGF-beta signaling to reduce expression of MMPs, and this in turn decreases degraded collagen levels associated with altered cell function[130,131].

In multiple biological systems, dermal fillers that artificially restore the matrix on which fibroblasts live, are demonstrated to increase collagen synthesis. This is likely accomplished by interrupting the defective signaling associated with fragmented collagen. Hyaluronic acid fillers, in human and mouse models, restore the ECM via dermal fibroblast collagen synthesis. In mouse models, hyaluronic acid filler also stimulates collagen and elastin synthesis[132,133]. Calcium hydroxylapatite, a semi-permanent biostimulatory filler, is also shown in tissue culture to restore the contractile properties of photoaged dermal fibroblasts[134].

Absorbable sutures are an emerging treatment that may also work through interruption of the altered signaling that is associated with fragmented collagen. Polydioxanone (PDO) and monofilament poly-lactic acid (PLA) absorbable sutures are posited to lift and tighten aging skin. In animal models, PDO and PLA threads on histology induce collagen-1 and -3 production two weeks after insertion. This benefit, however, sharply declines by 12 weeks post-insertion[135]. In another study, PDO sutures induced neocollagenesis, tissue contracture and improved vasculature four weeks after insertion, a change maintained at 48 weeks[136]. While molecular analysis has yet to be performed, it is possible that absorbable sutures induce physical contraction of skin and fibrosis to restore the stretch placed on fibroblasts, similar to an intact ECM.

Microdermabrasion, moderate to deep chemical peels, fractional radiofrequency microneedling, and fractional non-ablative and fractional ablative lasers, all demonstrate an induced wound repair response on histology[137-139]. Recent molecular analysis suggests that fractionated ablative CO2laser accomplishes this through alteration of inflammatory signal pathways, with damage-activating innate immune responses that in turn trigger the activation of retinoic acid-dependent pathways[140]. Interestingly, this process is mediated by NF-kB expression at significantly higher levels than those observed in chronically aged skin, indicating that the balance of signaling factors is crucial to regenerative responses.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an autologous blood product of concentrated platelets delivered via injection into target tissue. PRP is thought to contain over 800 bioactive molecules derived from platelet granules, including TGF-beta, epidermal growth factor, PDGF, FGF, IGF and angiogenic growth factors[141,142]. While demonstrated to have benefit for wound healing, arthritis, and more recently androgenetic alopecia, its use for photoaging is less well established. A systemic meta-analysis concluded modest clinical benefit of PRP for aging skin, mostly when used as an adjuvant following fractional and fully ablative laser resurfacing[143].

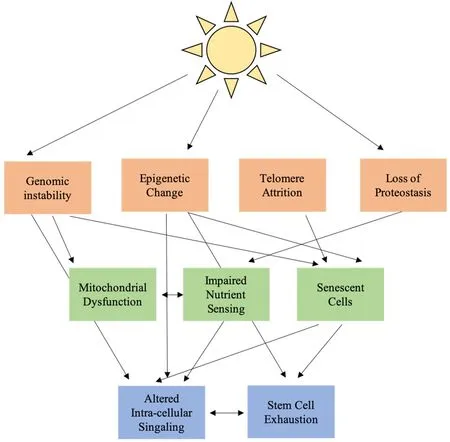

Figure 1. Interconnected hallmarks of aging in cutaneous photoaging

Many of the treatments discussed above target photoaging-related stem cell exhaustion but do not directly restore the stem cell population that is depleted with aging. The direct delivery of stem cells to target tissue has been used in many models of regeneration. Transplanted epidermal stem cells exhibit benefit the regeneration of epidermis lost in wound settings but have not been used for regeneration of intact photoaged epidermis[144]. Transplantation of an alternate cell population, that of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells, has benefit in vivo for both dermal and epidermal aging phenotypes[145]. The mechanism of action is unclear, but co-culture experiments demonstrate improved fibroblast synthetic function, suggesting the modification of the signaling milieu rather than direct stem cell regeneration[146].

CONCLUSION

Skin photoaging is associated with extensive functional and cosmetic changes. The classic hallmarks of systemic aging offer a framework for understanding the process of these changes on a molecular level [Figure 1]. In this framework, UV radiation works through ROS to induce primary changes in the nuclear genome, mitochondrial genome, epigenome and cell protein population. These primary changes lead to antagonistic changes in cell function, impaired mitochondrial function, dysregulated nutrient sensing and cellular senescence. Antagonistic changes result in altered cellular signaling and stem cell exhaustion, particularly increased low level NF-kB inflammatory signaling and decreased growth factor signaling, further amplified by changes in the ECM. Most current effective treatments for photoaging focus on the mitigation of ROSassociated damage through antioxidant supplementation and restoration of the intracellular signaling environment. Open areas for therapy include a focus on mitochondrial function and the process of nutrient sensing and clearance of senescent cells.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the review and performed data acquisition: Vandiver AR, Hogan SR

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

? The Author(s) 2020.

Plastic and Aesthetic Research2020年11期

Plastic and Aesthetic Research2020年11期

- Plastic and Aesthetic Research的其它文章

- Review on the treatment of scars

- Laser Resurfacing for the Management of Periorbital Scarring

- Strategies for innervation of the neophallus

- Microsurgical salvage of complex dorsal shearing injuries of the hand and wrist

- Hyaluronic acid for lower eyelid and tear trough rejuvenation: review of the literature

- Metoidioplasty using labial advancement flaps for urethroplasty