Thrombocytopenia with multiple splenic lesions - histiocytic sarcoma of the spleen without splenomegaly: A case report

Kai Huang, Alvaro Frometa Columbie, Robert W Allan, Subhasis Misra

Abstract

Key words: Histiocytic sarcoma; Spleen; Proliferation; Thrombocytopenia; Bone marrow metastasis; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a rare malignant neoplasm that occurs in lymph nodes,skin, and the gastrointestinal tract. It is a malignant proliferation of cells showing morphologic and immunophenotypic characteristics of mature tissue histiocytes[1],and represents less than 0.5% of all non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. HS of the spleen is a rare and potentially lethal condition that can remain asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic for an extended period[2]. The diagnosis depends on verification of histiocytic lineage and distinguishing HS from other benign or malignant diseases,such as benign histiocytic proliferation, hemophagocytic syndrome, malignant histiocytosis, and acute monocytic leukemia using immunohistochemical techniques and molecular genetic tools[3-5].

Due to its rarity, the number of “true” cases reported as primary splenic HS in the English literature are few (up to eight cases reported), with most recent references from 2012. The clinicopathological features of HS have not been well described.Primary splenic HS cases often show a multi-nodular lesion in an enlarged spleen,with no specific findings in imaging studies[6,7]. Patients with splenic HS have a poor prognosis due to the aggressive behavior of this entity, even though a splenectomy might induce temporary remission. Liver or bone marrow infiltration constitutes a common finding that partially obscures the prognostic evaluation. Early evaluation and diagnosis, before dissemination of the disease, may improve the prognosis and prospects of survival. We report a case of thrombocytopenia of unknown etiology with multiple splenic lesions and disseminated bone metastasis treated by laparoscopic splenectomy. The final diagnosis was low-grade HS of the spleen.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Left upper quadrant pain, drenching sweats.

History of present illness

A 40-year-old Hispanic female was referred to our clinic due to persistent thrombocytopenia and multiple splenic lesions. She initially presented with drenching sweats and left upper abdominal pain that was associated with progressive thrombocytopenia for four months. She denied recent weight loss, fever, or chills.

History of past illness

The patient denied previous medical or surgical history.

Personal and family history

Not contributory.

Physical examination upon admission

On physical examination, no hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or superficial lymphadenopathy was observed.

Laboratory examinations

Initial assessment revealed thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 37000/mm3.Her white blood cell count was 10300/μL, and hemoglobin was 14.0 g/dL. The biochemistry profile was unremarkable. Further study of serum protein electrophoresis, peripheral blood flow cytometry, and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the right cervical level II lymph node was unremarkable. She had two bone marrow biopsies, which did not show evidence of lymphoproliferative disorder.

Imaging examinations

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spleen demonstrated a normal-sized spleen(greatest dimension 10 cm) with multiple T1 hypointense/T2 hyperintense lesions,suggestive of possible extramedullary hematopoiesis or lymphoma. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET/CT) showed mild uptake (standardized uptake value (SUV) 3.5) in one of the lesions along the splenic hilum. All other splenic nodules were non-avid. A small cervical node (SUV 3.3), left breast nodule (SUV 2.1),and several bone sites (brightest at T3, SUV 4.3) were also noted.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Low-grade HS of spleen.

TREATMENT

Diagnostic assessment and treatment

The patient was started on 40 mg of prednisone. This was progressively increased to 80 mg daily, with some improvement in her platelet count, which had been stable at 75000/mm3. She was otherwise doing well. She had no complaints of fever or weight loss, and no enlarged lymph nodes or neurological symptoms were noted on physical examination. The case was discussed at a tumor board. A decision was made to perform laparoscopic splenectomy. The patient was placed on a steroid taper with prednisone, 20 mg daily, preoperatively. Subsequently, her platelet count was hovering around 41000/mm3.

During surgery, a 10 mm trocar was inserted at the mid-clavicular line between the umbilicus and the left costal margin, and three trocars (10 mm, 5 mm, 5 mm) were placed at the anterior axillary line and midline during the procedure. A laparoscopic view showed a normal-sized liver and spleen, with no accessory splenules visualized.In addition, no metastatic or disseminated lesions were detected. The spleen was extracted from a 4 cm midline incision. The operation time was 2 h, and blood loss was 150 mL. To address her thrombocytopenia, 20 U of platelets were transfused after splenic vessels were transected.

Pathological findings

Gross specimen: The weight of the resected spleen was 110.1 g and measured 12 cm ×8.0 cm × 3.6 cm. There were numerous nodular, tan, rubbery, well-circumscribed lesions with smooth surfaces. The lesions were located within the subcapsular sinus and splenic parenchyma (greater than ten lesions).

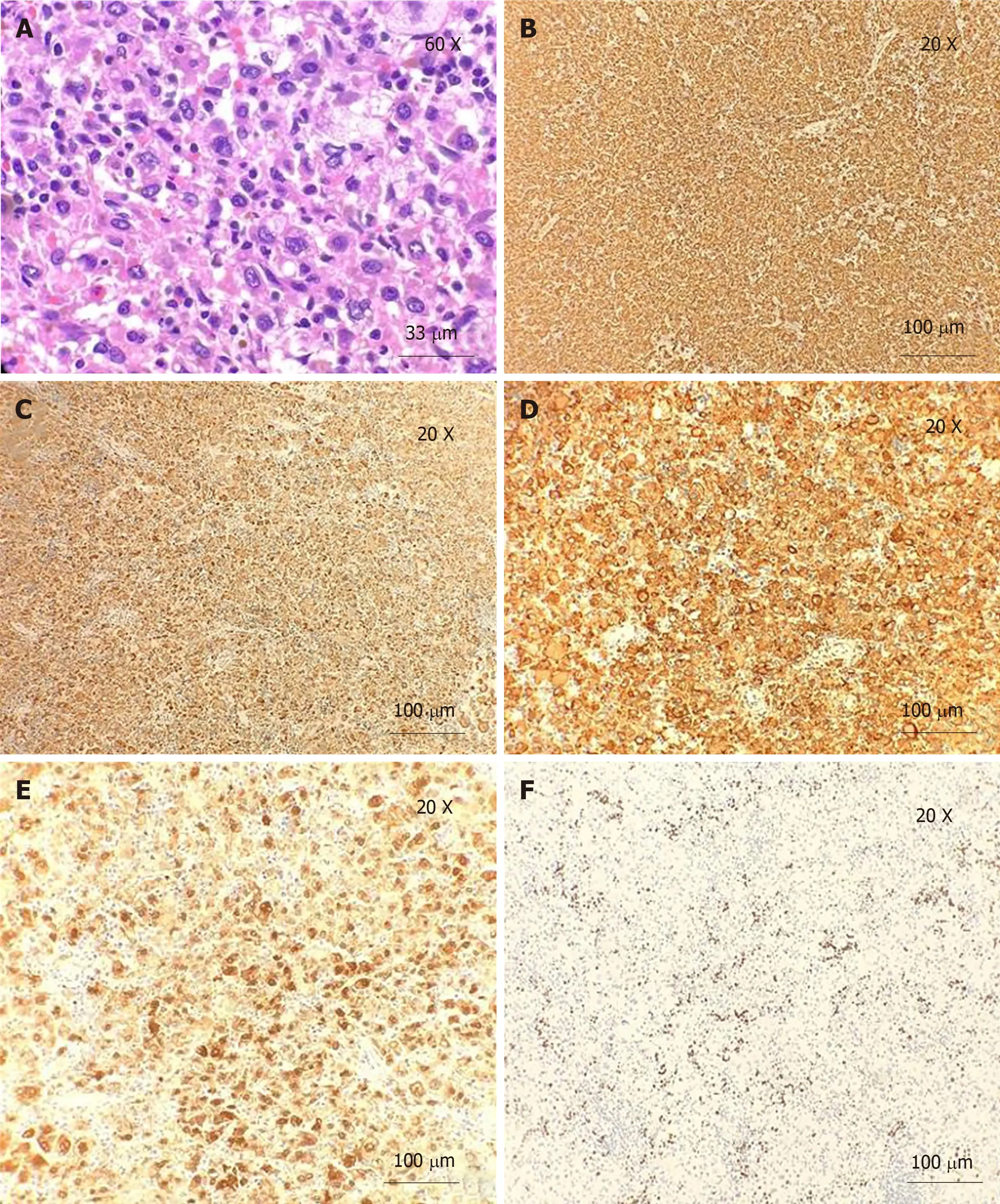

Microscopically, the H and E-stained sections showed a spleen with multinodular proliferation of histiocytoid cells. There was an accompanying infiltrate of scattered small lymphoid cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils. The histiocytoid cells had abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and showed variable nuclear atypia (Figures 1 and 2). Immunohistochemistry showed immunoreactivity for CD163, CD4, and CD68,factor XIIIa, and CD14. The Ki-67 showed a proliferative index of 10%. Only rare mitotic figures, with rare atypical mitoses, were noted. The patient’s pathologic diagnosis was difficult. After consulting two renowned pathology institutions, the final pathologic diagnosis was HS of the spleen.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW UP

Figure 1 H and E staining and immunohistochemistry. A: H and E staining. Neoplastic cells have abundant eosinophilic and vacuolated cytoplasm, with a large eccentric nucleus and prominent nucleoli (60 × magnification); B: Immunoreactivity for CD163 (20 × magnification); C: Immunoreactivity for CD68 (20 × magnification);D: Immunoreactivity for CD4 (20 × magnification); E: Immunoreactivity for Factor XIII (20 × magnification); F: Ki-67. Proliferation index is approximately 10% (20 ×magnification).

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient’s platelet count normalized after surgical intervention: 13900/mm3on postoperative day one (POD1) and 16300/mm3on POD2. The patient was discharged on POD2 with instructions to follow-up one month after surgery. She has been feeling well and had marked improvement in pain and night sweats, with platelet values remaining stable. She has not noticed any enlarged lymph nodes, fever, weight loss, or neurological deficits. The patient was seen at a renowned cancer center after a final diagnosis of low-grade HS.Her repeat PET, one month after surgery, showed low avidity of bone marrow without interval changes. She remains in observation without adjuvant treatment.However, her five-month PET scan showed progressed bone marrow metastasis. She is waiting to be enrolled in a clinical trial.

DISCUSSION

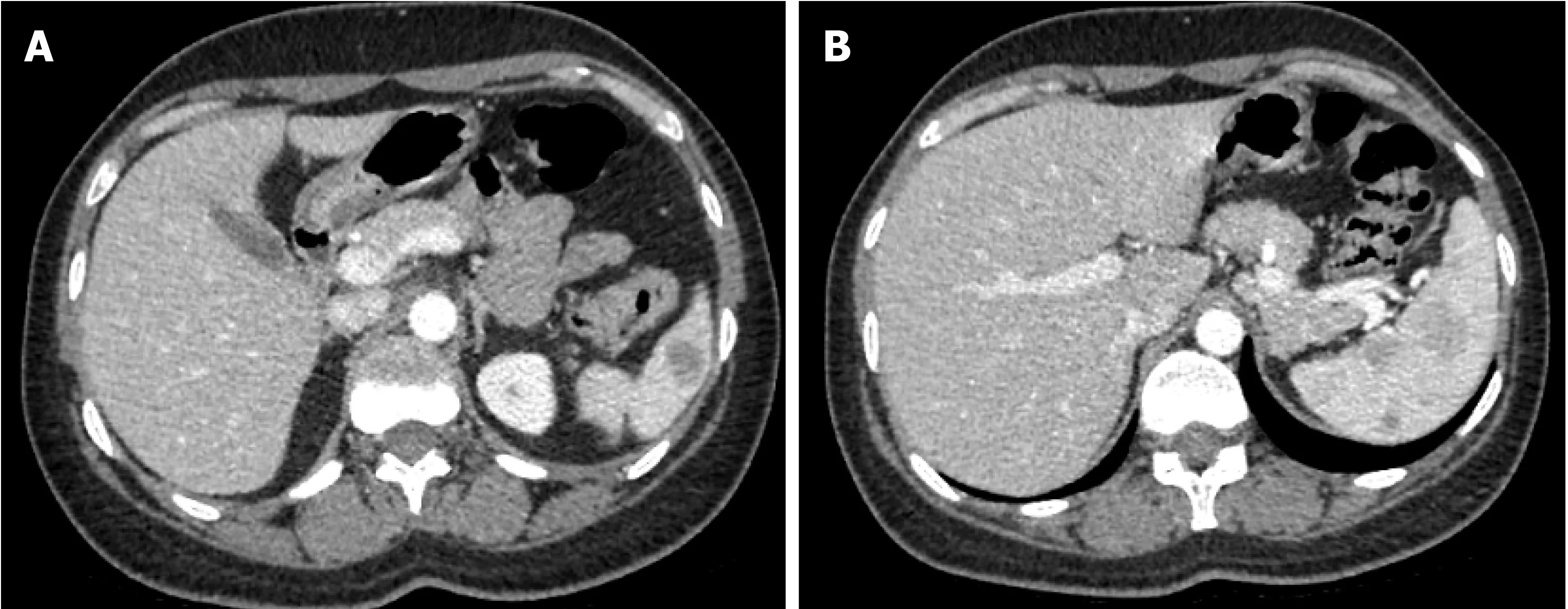

Figure 2 Computed tomography. A, B: Spleen shows multiple circumscribed intermediate density lesions of variable size and varying enhancement, with the largest at the hilum measuring 2.4 cm × 2.1 cm and 2.7 cm × 2.1 cm. The differential diagnosis includes lymphoma, splenic peliosis, infection with multiple abscesses, and metastasis.

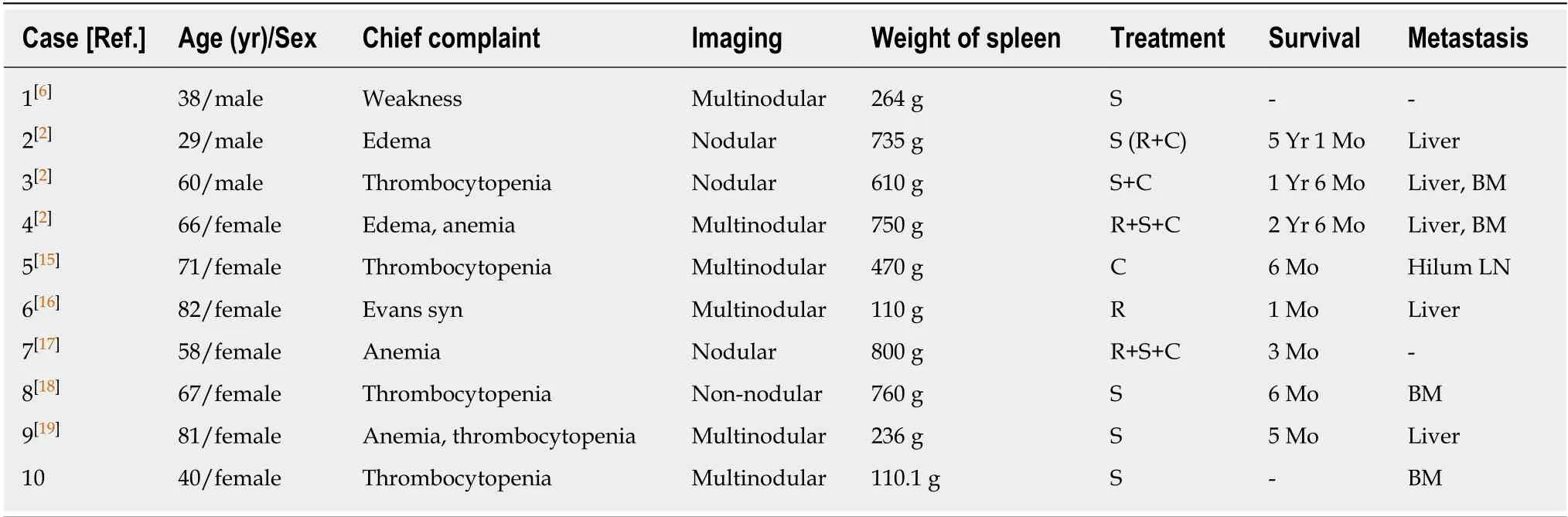

HS is a rare malignant proliferation of cells showing morphologic and immunophenotypic features, similar to mature tissue histiocytes. Clinically, it is generally accepted that most patients with HS have a poor prognosis due to early disseminated disease and limited response to chemotherapy[8]. Previous cases, including extra-nodal HS of non-splenic origin, showed that the stage of the disease and possibly tumor size can be important prognostic indicators[9,10]. HS of the spleen is a rare condition, and its clinicopathological features have not been well described[7]. According to the nine cases reported so far (Table 1), the majority of patients are female (6/9), with an age range of 29-82 years (median 67), and presented with thrombocytopenia and multinodular lesions in the setting of splenomegaly. The most common distant metastases are liver and bone marrow. Survival time ranges from 1 month to 5 years(median six months). Early diagnosis, before dissemination of this disease, may improve the prognosis. Extra-nodal extension and bone marrow involvement with consequent cytopenia (due to hemophagocytosis) obscure the prognosis.

The diagnosis of HS was based on histology and cytomorphology examinations,along with an immunohistochemical profile that pointed toward histiocytic lineage.Histologically, the lesion was composed of non-cohesive large cells with polygonal to cuboidal shape. These large neoplastic cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with vacuoles and a large, oval, eccentrically-located nucleus with vesicular chromatin and prominent, irregular nucleoli. Rarely, hemophagocytosis and giant cells may also be seen.

Cytomorphologic findings are not specific for HS; hence, immunohistochemical stains were utilized to prove histiocytic differentiation. The neoplastic cells were positive for CD68, CD163, CD14, CD4, CD11c, lysozyme, and alpha-1-antitrypsin and negative for epithelial and hematolymphoid differentiation markers. The proliferation index was highly variable, demonstrated by Ki-67 (range from 1 to 99%). Some genetic aberrations have been variably detected in cases of HS, among which BRAF (present in up to 70% of cases),HRAS, andBRAFgene fusion are the most frequently linked.

The conclusive diagnosis of HS is based on not only histological and immunohistochemical examination of histiocytic differentiation but also exclusion of other immunophenotypes, including lymphoid, epithelial, and melanocytic differentiation. Among the differential diagnoses, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH),hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, follicular cell sarcoma, and interdigitating cell sarcoma are among the most emphasized. HS and LCH are both determined by histiocytic proliferation. However, these entities have structural, enzymatic, and immunohistochemical differences that allow for proper differentiation in the majority of cases. The presence of positive immunohistochemistry for alpha-1-antitrypsin and lysozymes in this case effectively ruled out LCH. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma was also discarded using the same criteria for LCH. Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma shares an immunohistochemical profile closely related to HS, while still being negative for alpha-1-antitrypsin.BRAFmutation has not been detected in these cases.The presence of positive staining for lysozymes can obscure the differential diagnosis;however, the ultrastructural examination demonstrated the scattered distribution of these instead of abundant and evenly distributed lysozymes in HS. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is also a neoplastic proliferation of histiocytes by definition.Hematophagocytosis, while found in both entities, is more common and prominent in the former and constitutes a rare finding in the latter.

Imaging findings are essential for the early diagnosis of HS. However, satisfactory diagnostic imaging characteristics are still lacking. Contrast-enhanced CT scans demonstrated multiple, partially confluent, hypoattenuating masses in the enlarged spleen with multiple liver infiltration, and ultrasonography revealed multiple, illdefined hypoechoic lesions. HS commonly presents as multiple hypointense T1 and hyperintense T2 lesions on MRI, which can also be found in cases of splenic neoplasmsuch as splenic lymphoma, hemagiomatosis, or angiosarcoma. Case reports have indicated the possible role of PET scan in histiocytic lineage disorders, such as LCH[12],and PET scans can be very valuable in the evaluation of disease dissemination and tailoring treatment in HS[13]. In our patient, initially, among those multiple splenic lesions on MRI, only one of the lesions along the splenic hilum showed a mild SUV of 3.5 on PET/CT, and all other splenic nodules showed non-avidity on the PET scan.No significant interval avidity changes were seen at previous active bone sites in the repeated PET scan three months later. However, progression of bone marrow metastasis was seen five months later, which is consistent with the characteristics of low-grade disease.

Table 1 Comparison of main clinical features among the reported cases with primary splenic histiocytic sarcoma (including our case)

Splenectomy is useful for definitive diagnosis of the disease. At the early stage of the disease, splenectomy would be expected to be beneficial for those with HS of the spleen to prevent continuous dissemination from the primary tumor site. Our patient presented with multiple splenic lesions with a disseminated bone lesion. Two bone marrow biopsies and FNA of lymph nodes were inconclusive concerning the diagnosis. Moreover, our patient suffered from progressive thrombocytopenia.Laparoscopic splenectomy was performed for both therapeutic and diagnostic purposes. There is no standard treatment regimen for patients with HS, and patients should be encouraged to enroll in a clinical trial if one is available[14]. Adjuvant treatments of HS include radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and combinations thereof,depending on the stage of the disease. Lymphoma-type systemic chemotherapy has been recommended for multiple systemic diseases. Nine previously reported cases of HS of the spleen recovered asymptomatically after splenectomy for a definitive diagnosis (including five patients who underwent subsequent chemotherapy[2]). All but one patient (who was alive 13 mo after splenectomy and whose outcome is not yet known) died from liver infiltration[6,15].

Our patient presented with disseminated bone metastasis and multiple splenic lesions, without initial splenomegaly. Her bone marrow metastases were stable and then progressed at eight months after diagnosis without adjuvant treatment. She remains in good performance status without other distant organ metastases. Her lowgrade differentiated tumor may be associated with a slow progressive disease.

CONCLUSION

HS of the spleen is a rare, lethal disease. The pathologic diagnosis can be difficult due to its differentiation with malignant LCH or other benign histiocytic proliferation, as in our case. PET scans can be very valuable in the evaluation of disease dissemination.Low-grade differentiation may be associated with a slow progressive disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Nguyen Quoc-Han, MD, for language and grammar revision and LeAnn Garza of English Pro, LLC for substantive editing of this manuscript. This research was supported (in whole or part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

World Journal of Clinical Oncology2020年3期

World Journal of Clinical Oncology2020年3期

- World Journal of Clinical Oncology的其它文章

- Glycoconjugation: An approach to cancer therapeutics

- Assessment methods and services for older people with cancer in the United Kingdom

- Efficacy, patterns of use and cost of Pertuzumab in the treatment of HER2+ metastatic breast cancer in Singapore: The National Cancer Centre Singapore experience

- What factors influence patient experience in orthopedic oncology office visits?

- Roles of cell fusion, hybridization and polyploid cell formation in cancer metastasis