The economic lives of Americantrained Chinese scientists after they returned to China in the 1950s: A case study of Huang Pao-tung and Feng Zhiliu

Peking University, China

Abstract This article is a case study of Huang Pao-tung (1921-2005), who was a polymer chemist and academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his wife, Feng Zhiliu (1921-2015), who was a polymer physicist.The couple studied in America and returned to China in the 1950s.Based on an analysis of first-hand data from the two scientists’ archives,diaries and memoirs, which recorded their economic lives after they returned, I found as follows: (1) their income after returning to China was about one-fifth of their income in the United States; (2) their income channel was narrow(there was no mechanism for wage increases, and their wages were unchanged for 25 years); (3) the main expenditure of their family was on food, and that proportion increased year by year; and (4) no taxes, low rents, free medical care and other benefits helped to reduce their cost of living in China.The importance of their profession as scientists and the government’s advocacy of scholars returning home brought them relatively good treatment, and their economic benefits and living standard were several times better than those of other ordinary social classes.However, this kind of preferential treatment was dependent on many other things, which caused them to lose independence and autonomy.

Keywords American-trained Chinese scientists, economic life, scientists’ salary, Huang Pao-tung, Feng Zhiliu

As a new occupational group that emerged in 20thcentury China, scientists had and continue to have an important influence on the country’s historical development.In the 1950s, under the vigorous advocacy and effective organization of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the newly founded Government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a large wave of Chinese scientists and students studying abroad returned to the country.According to data from an official 1956 document (A Report on Job Assignments of Students Returning from Capitalist Countries), as many as 1536 senior intellectuals returned from Western countries in the period from August 1949 to November 1955.Among them, 1041 people came back from the United States (US) (Jin, 2008: 1077).After the beginning of the ‘Anti-Rightist Movement’in 1957, the number plummeted and only a few people returned to China.

According to the latest research, there were about 5000 Chinese students in the US in 1949(Wang, 2010).Less than half of them chose to return to China at that time, so two scientist groups formed: those who returned and those who stayed in the US.Research on the two groups, especially comparative studies, has received much attention from historians of science.However, because historical material is limited and this kind of research is difficult (the people involved are numerous and scattered; little historical data was retained because of political pressure at the time; transnational research is needed), few scholars have been involved in the field (see He et al., 2007; Hou et al., 2013; Li, 2000; Wang, 2010; Wang and Liu,2012; Wang and Zhang, 2018).There remains a lack of clear, detailed descriptions and accurate data to assess the economic conditions of scientists who returned.

Huang Pao-tung, an expert in the field of polymer chemistry in China, and his wife Feng Zhiliu studied in the US.After returning to China in 1955,they worked in the Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry (CIAC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) until they retired.Huang’s diary manuscripts, which were collected by the Project on Collecting the Historical Data of Chinese Scientists’ Academic Life organized by the China Association for Science and Technology, recorded their living conditions in the first few years after their return, including their monthly income and expenditure details from 1955 to 1960.1Based on those materials and statistics, in this article I analyse their wage level, sources of household income,specific expenditure structure and changes in it over the years, and the balance of their income and expenditure before and after their return, thus illustrating the economic lives of Chinese scientists in the early years of the PRC.By combining background information on China’s political,social and economic situation, wage systems and policies relating to intellectuals in the 1950s, I also explore the attitudes of the newly established government to the returning scientists and changes in that attitude.

1.The economic conditions of Huang Pao-tung and Feng Zhiliu after their return to China

Huang Pao-tung (1921-2005), who was born in Shanghai, was a polymer chemist and an academician of CAS.He graduated from the Chemistry Department of the Central University in 1944, studied in the US from 1947 and received his PhD from the Brooklyn Institute of Technology in New York in October 1952.He then worked in the Plastics Research Laboratory at Princeton University.

Feng Zhiliu (1921-2015), who was born in Haiyan County, Zhejiang Province, was a polymer physicist.She graduated from the Textile College of Nantong University in 1944, studied in the US from 1946, received a master’s degree in science from the Rowell Textile Institute in Massachusetts in 1948,and then worked as a visiting scholar at the National Bureau of Standards in Washington DC.In 1950, she began to work as an engineer at the Textile Research Institute in Princeton, Jersey.

Huang and Feng met in November 1952.In October 1953, they married in the US.In March 1955, both of them resigned and returned to China(Figure 1).They arrived on the Chinese mainland via Hong Kong in early May.

Before they officially joined CIAC at the end of October 1955, Huang and Feng visited Shanghai,Beijing and Changchun, visiting relatives and friends and waiting for assignments.At that stage, they had no formal income and lived on their savings.During that period, they also borrowed money from CAS and CIAC.After they joined CIAC, their family income and expenditure stabilized.In March 1956, the academic department of CAS assessed their professional titles and decided their salary levels.Huang was rated as an associate researcher with a monthly salary of 187.92yuan, and Feng was rated as an associate researcher with a salary of 172.8yuan.In 1956, after the national wage adjustment, their monthly wages were raised to 207yuanand 177yuan, respectively.Their total annual salary income was 4608yuan.

Figure 1.Huang (first from left) and Feng (second from left) on board the SS President Wilson on their way home in 1955.

According to Huang’s written records, the couple’s average annual expenditure during the period from 1956 to 1960 was 5280yuan.If they had relied only on wage income, it would have been difficult to pay for household expenses.They used the money that they had accumulated in 1955 and 1956 when family expenses exceeded their wage income.In addition to their savings, they had several other sources of income: a reimbursement of more than 1200yuanfor international travel from the US to China; nearly 500yuanfrom CAS for books that Huang bought in the US; a settling-in allowance of 1000yuanfrom CAS in August 1956(500yuanfor each); and about 350yuanfrom Huang’s mother and mother-in-law.From 1956 to 1960, Huang’s family deposit averaged 7100yuan,which would earn 400yuanin interest each year -far more than the average annual income of about 50yuanfor writing articles.

The family’s main expenditure was on food.In 1956, they spent about 102.5yuana month on food,or 26.5% of their total household expenditure.That proportion grew year on year, rising to 38.4% in 1960.According to the Engel coefficient, which measures the standard of living of families, their household affluence declined year by year, but they were still much better off than the average urban Chinese family (the coefficient of which was 58.4%in 1957) (National Bureau of Statistics, 1984: 463).

In addition to food expenses, about one-fifth of the household expenditure went to support their mothers, and about one-tenth was used to pay a nanny.Together, food, parental support and the nanny accounted for 60% to 70% of their total household expenditure.

Other regular expenses included transportation,rent, medical expenses, daily necessities and cultural and entertainment expenses.Culture and entertainment required only about 5% of their spending.On Sundays (they worked as usual on Saturdays), they would read books and newspapers, write letters, listen to records, go shopping, watch movies and dramas, eat Western food and visit parks.Since most of the films were free, the cost was not significant.

2.Comparison between Huang and Feng’s income and expenditure before and after their return

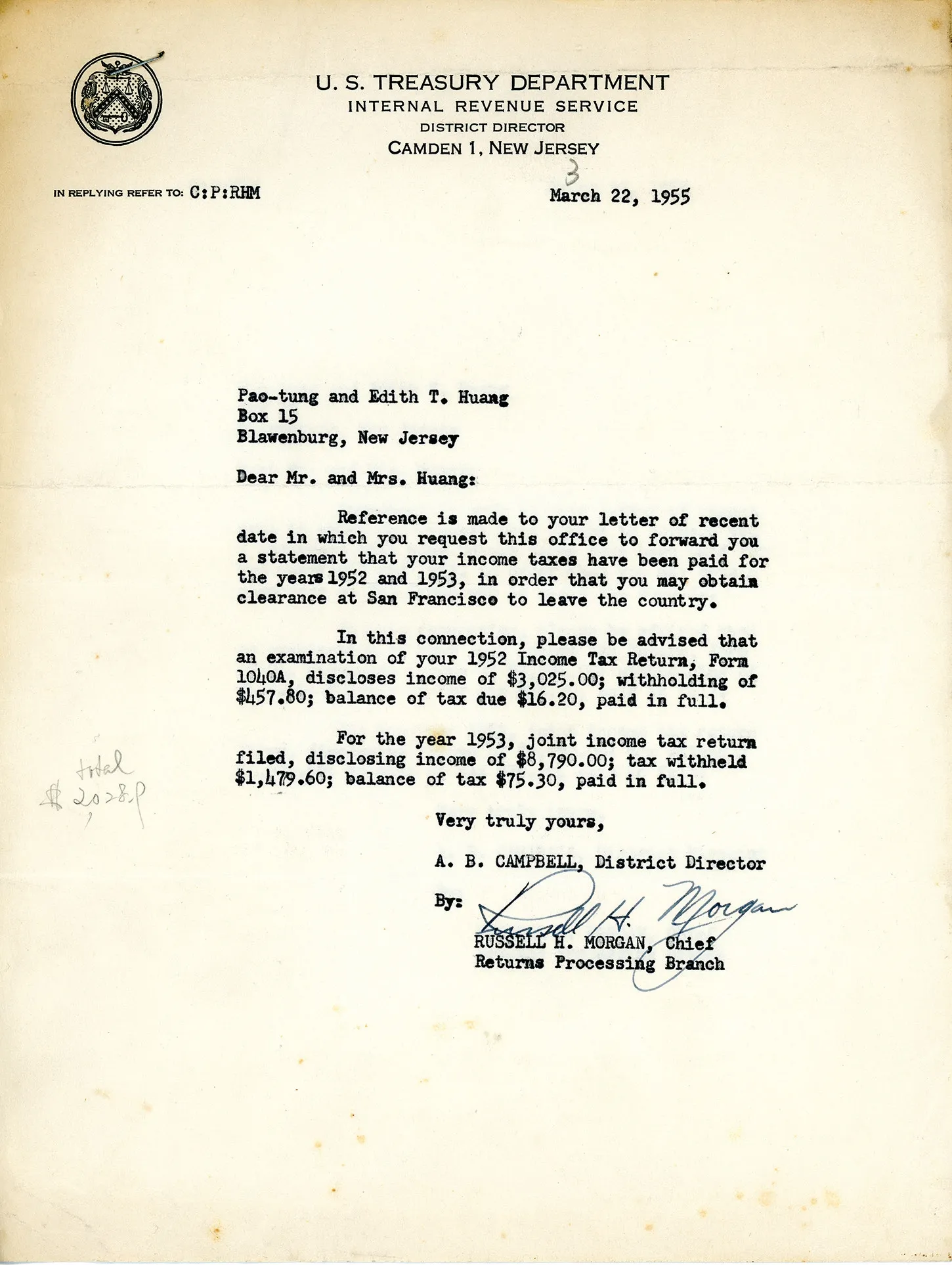

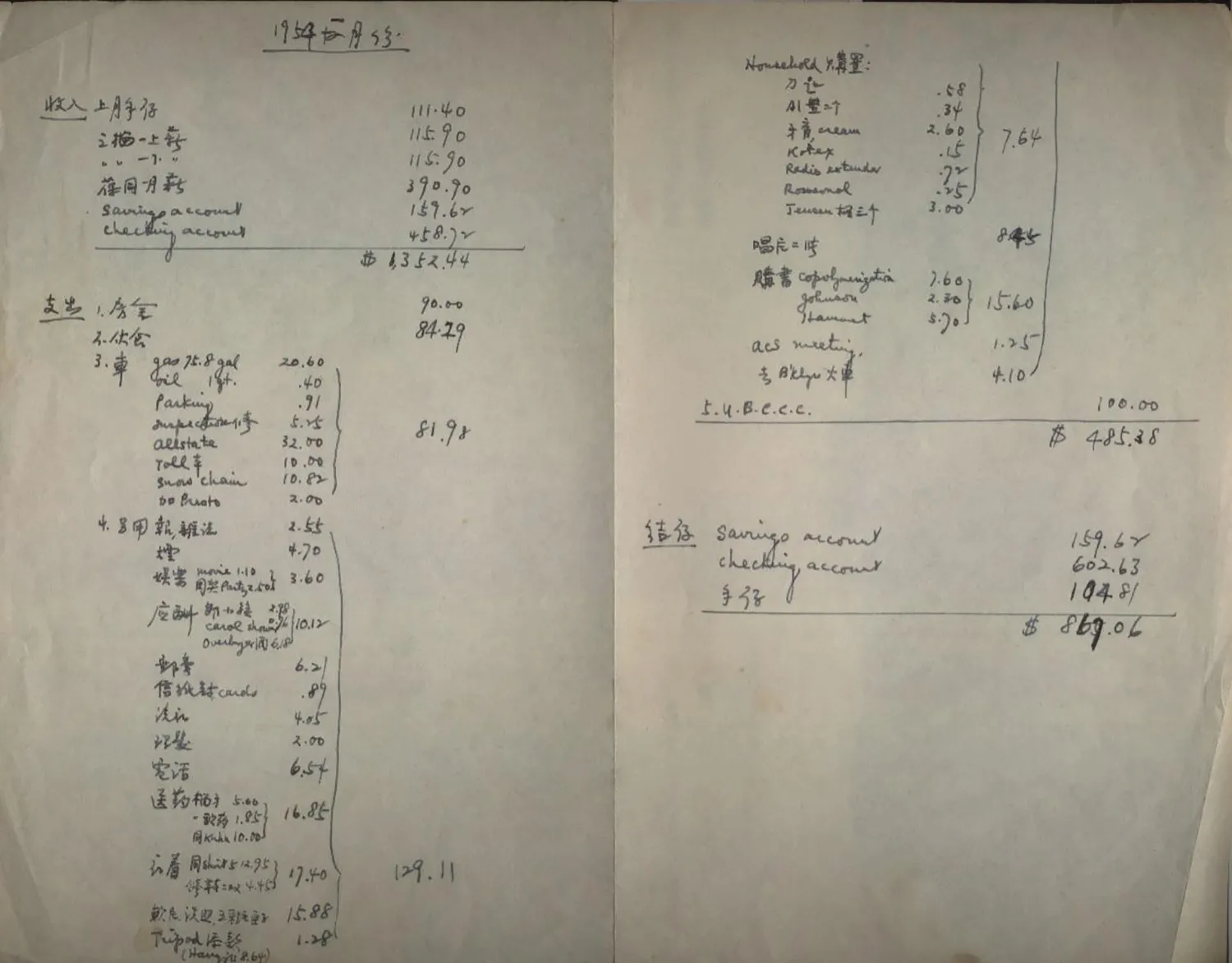

In 1955, before Huang and Feng left the US, US authorities required them to provide proof of their tax payments during their stay.They demonstrated that their income was $3025 and they paid $474 in tax in 1952; in 1953, their income was $8790 and they paid $1554.90 in tax (Figure 2).According to the details of income and expenditure in January 1954 recorded by Huang, Huang’s salary was$390.90 in that month and Feng’s was $231.80,totalling $622.70.In the same month, they had a saving account of $159.62, a checking account of$458.72 and $111.40 in cash (Figure 3).

In 1968, Huang recalled that their annual income in the US before 1955 amounted to $9600, including$6000 from Huang and $3600 from Feng.Thus, their annual income before returning to China was $9000 to $10,000.According to a survey conducted by CAS at the end of 1955, senior US scientists were usually paid an annual salary of $10,000 to $20,000, and ordinary scientists $5000 to $10,000 (CAS Archives,1955).The wage levels of Huang and Feng were basically consistent with that.Calculated using the USD to RMB exchange rate of 2.4618 in 1955, their annual income in the US was about five times their annual income after they returned to China.

Figure 2.Tax payment proof of Huang and Feng in 1955.

Their income in the US was high, but so was their expenditure.Their total expenditure in January 1954 was $485.38 (Figure 3), including a monthly repayment of $100 to the United Board of Christian Colleges in China,2which accounted for 20% of that expenditure.Other large monthly expenses included $90 for rent,$84.29 for food and $81.98 for the use and maintenance of their car, which together accounted for 52.8%.

Figure 3.Income and expenditure in January 1954 recorded by Huang.

A comparison between specific expenditures before and after their return to China revealed that their expenses for rent, food, transportation and medical care were higher in the US.Their rent was$90 per month in the US, or 18.5% of their total monthly expenditure.After returning to China, their rental expenses were relatively low, averaging 8.2yuanper month, accounting for only 2% of their monthly expenditure.Their food expenses were more than $80 a month in the US (17.4% of their total expenditure); in China, those expenses were about 100yuanper month (26.5% of their total expenditure).For transport, they used private cars in the US, costing them about $80 for use and maintenance (16.9% of total expenditure); in China, they could use official cars in emergencies, such as illness, and for business travel.Usually, they would travel in the city by public transport or tricycle, and their monthly expense was about 10yuan(only 2.7%of their total expenditure).In China, they enjoyed free medical treatment.When it was necessary to purchase medicine, the expense was far less than in the US.Cultural and entertainment expenses accounted for a relatively small proportion of their monthly expenditure (about 10% in the US and only 5% in China).In addition, their personal income tax rate was 17.7% in the US in 1953.In the early days of the PRC, there was no income tax in China.

According to a survey conducted by CAS concerning the life of Chinese scientists in the US:

The average rent accounted for 10% of their wage income.The condition of their housing was similar to that in China, but the equipment was better; transportation was more convenient; the price of cloth and wool fabrics was about the same as in the domestic [Chinese] market;their food was better than in China, mainly comprising meat and milk, supplemented by staple foods.A family of three people that enjoyed a medium level of life needed $300 per month.(CAS Archives, 1955)

The monthly expenses of Huang and Feng were obviously higher than that level.High income and high consumption were the prevailing conditions among Chinese scientists in the US.Therefore, many of them could not accumulate large amounts of money.When returning to China, Huang and Feng had only about $1000 with them.

3.Changes in the wages of scientists who returned from the US in the 1950s

To develop China’s scientific culture after the founding of the PRC, specialists were highly valued by the CPC and the central government.In addition to recruiting the scientific researchers of the former National Government and cultivating its own scientific and technical personnel, the government also tried to encourage Chinese scientists who were overseas to come home in order to overcome the serious shortage of senior scientific and technological talent.

At first, patriotism and political propaganda were the main tools of the government and produced remarkable results in a short period.From August 1949 to December 1951, a total of 1144 students returned to China, including 821 returning from the US (Zuo, 2016).Among them were scientists with high social prestige, such as Hua Luogeng, Ge Tingsui and Zhao Zhongyao.However, most of them were students who had just graduated or had worked for a few years, such as Deng Jiaxian, Zhu Guangya and Ye Duzheng.After they returned to China, they were welcomed by the government and enjoyed preferential treatment.However, some preferential treatment was not universal but was targeted at scientists with higher prestige.There were also many problems in placing the students:

Many specialized students were assigned to jobs that were incompatible with their majors.It would take a long time to achieve an academic title.Some were awarded no title even after two or three years from their return to the country; some were given a low title and a very low salary.(Shanghai Archives, 2016: 320)

In 1954, CAS conducted a survey on the living conditions of senior intellectuals.The survey specifically mentioned that several scientists had problems in adjusting their lifestyles.For example,Yang Chengzong, a researcher at the Institute of Physics, earned 650 points a month.3His wife had no job, and they had three children.They had difficulties even in buying clothes, books and magazines, despite a monthly subsidy of 30yuan.Thus Yang had no choice but to sell apparatus that he had brought back for research.There were many other such cases.

At the end of 1955, the CPC Central Committee adjusted its policies relating to intellectuals, changing its focus from ‘transforming’ them to ‘using and training’ them.Solving the problem of the treatment of senior intellectuals became a top priority.In February 1956, Zhou Enlai delivered important instructions regarding theReport on Encouraging Students to Return Home from Capitalist Countries,which was delivered by the working group that was responsible for this matter.He stated that ‘a(chǎn)ll departments in all regions should conduct a general inspection, solving the problem of improper job assignment and improving working conditions and treatment’ (General Office of the Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee and the Editorial and Research Department of the Central Archives, 1996: 1085).After that, students returning from abroad received greater attention.They were now paid more than other scientific researchers with the same qualifications and educational backgrounds.They were paid a settling-in allowance, and senior experts were usually offered personal apartments.Some enjoyed special benefits in the form of a fixed amount of supplies each month(Xie et al., 2008).

In 1956, wage reforms were carried out nationwide, and the wages of scientists were greatly improved.The salaries of scientific researchers of CAS were an example.Researchers and associate researchers were paid 149.5 to 345yuanper month;senior researchers were paid 450yuanper month(Zhu, 2008: 354).Hua Luogeng, Zhao Zhongyao and Qian Xuesen, who returned from abroad, were senior researchers.At that time, the monthly salary of national leaders such as Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Enlai and Zhu De was 581yuan(Zhang, 2009: 112), so the salaries of some senior scientists were relatively high.

Reputable scientists with higher prestige would often be offered some extra income.For example,in 1954, National People’s Congress representatives enjoyed a monthly subsidy of 50yuan; in 1955, members of CAS, of whom more than 90%had backgrounds in the natural sciences and had studied abroad, had a monthly allowance of 100yuan(Li, 2000: 183).In 1957, Hua Luogeng,Qian Xuesen and Wu Wenjun, all of whom were scientists who returned in the 1950s, won the first prize in the Science Prize and were awarded 10,000yuan.A number of scientists who returned from abroad won the second prize and the third prize and were awarded 5000yuanand 2000yuan,respectively.The prize money was equivalent to the salary of a general scientist over several years(Guo, 2008).

However, few scientists who returned in the 1950s had high prestige, and most of them were young.Their salary was, like that of Huang, about 200yuanper month, and there were few other allowances.Their standard of living varied from person to person.In general, most families were relatively well off, but not wealthy.

Some families could not enjoy a high living standard even if they had a high income.For example, Tang Youqi and Zhang Lizhu were returnees who had studied abroad.Their combined salary was higher than that of Huang and Feng, but it was difficult for them to save money.Zhang recalls that, in 1953 and 1954, the family added two children, and their wages were all used to pay for two nannies and a cook (Committee of Cultural and Historical Data of the CPPCC, 1999: 325).

After the salary adjustment in 1956, scientists’wage income did not increase substantially for a long time.According to a survey conducted by CAS in 1963, most science and technology employees, especially senior research and technical personnel who returned from capitalist countries, had not been promoted since 1957 (CAS Archives,1963).Huang was rated as a fourth-level associate researcher in 1956, with a salary of 207yuan.It was not until 1982 that he was promoted to a fourthlevel researcher, and his salary increased to 212yuan.That means that Huang’s salary remained the same for about a quarter of a century.Moreover,the special treatment enjoyed by scientists was weakened or cancelled during the development of various political movements.As I have mentioned above, members of CAS enjoyed a monthly subsidy, but that treatment was attacked by many large newspapers after the beginning of the Rectification Movement in 1957, and many members gave up the allowance (CAS Archives, 1959a).

4.Discussion and conclusion

After the establishment of the new PRC Government in 1949, due to the low level of the national economy, the country implemented the policy of low wages and the egalitarian principle of ‘five people share three people’s meals’ (三人飯五人吃).At that time, due to shortages of food and other materials, the economic lives of scientists were frugal.

In the case of Huang and Feng, we can draw the following conclusions:

(1) After they returned to China in 1955, their economic income was much lower (about one-fifth) than it had been in the US.

(2) Due to the lack of a salary promotion mechanism, they had no salary increase for 25 years after 1956.

(3) The main expenditure of their family was on food, and that proportion increased year by year.

(4) They found that it was difficult to cover their household expenditure by using their wage income alone.

(5) Interest from their savings and relatives’ support were their main sources of non-wage income.

(6) No income tax, low rent, free medical services and other benefits reduced their cost of living.

(7) Shortages of supplies and the coupon-based supply system restricted their consumption,allowing them to accumulate some savings.

(8) Their economic condition and standard of living were better than those of ordinary workers.

Although the economic position of Americantrained Chinese scientists who returned to China was quite different from their position in the US,the importance of their profession and the government’s advocacy for their return brought them relatively good treatment.Thus, they were better off than many other social groups.However, their superior economic treatment was just a result of policies adopted by the government, and it could change as the situation developed.Such change began in the late 1950s and became more apparent in the 1960s.

Their preferential treatment was not protected by a contractual system and related laws, causing a loss of their independence and autonomy after their return to China.They now had to follow national arrangements and change their lifestyle to one of self-discipline.For example, when Huang Pao-tung returned to China, he could make his own choice about where to work.However, he followed the arrangements made by the Personnel Bureau of the State Council and went to CIAC.4

After returning to China, as a political task,Huang wrote letters to his Chinese acquaintances abroad to encourage them to return home.Also, to meet China’s needs, he changed his research directions several times, so that he produced no decent results for many years.He once claimed, ‘I, like the other students who returned to China in the same period, have not made any academic achievements for more than 10 years.In contrast, my classmates and colleagues in the US have already published many papers’.5

On 5 November 1955, CIAC held a welcome meeting for Huang and Feng.On the same day,Huang wrote in his diary: ‘Our colleagues regard us as senior researchers and have expressed high expectations for us to provide guidance in their work.We feel guilty and have to work hard and make more contributions in the future’.However, in subsequent diary entries, the words ‘busy’, ‘tired’ and ‘extremely tired’ began to appear frequently, and he would also complain that ‘I’m terribly busy; there are so many things to do and so many meetings to attend.’ This change in feelings may reflect the lives of many American-trained Chinese scientists after their return in the 1950s.

After 1957, it became more and more difficult to encourage scientists who had studied abroad to return home.Instead, some scientists began trying to leave.For example, Tang Shoubo, of the Institute of Electronics of CAS, was dissatisfied with his status, income and political life after he returned to China from Malaysia in 1957.He wrote to the British Embassy several times and asked for a visa to go to Malaysia via Hong Kong.He was allowed to return to Malaysia with his wife in May 1959.When he arrived in Singapore, he made a speech saying that he could not bear the lifestyle in China.In another example, Min Naida, known as the pioneer of computer science in new China, once attended various institutions, such as the Institute of Mathematics, the Institute of Computing and the Institute of Electronics of CAS.His wife, a West German, did not want her children to go to Chinese schools and was not properly cared for on a daily basis.In 1957, with the approval of the State Council, Min was allowed to go to East Berlin to enrol his children and engage in the work of writing books at the German Democratic Republic Academy of Sciences.Min took German citizenship after arriving in East Germany.There were also unsuccessful attempts; Shi Lvji, of the Institute of Biophysics of CAS, wrote to Premier Zhou Enlai twice asking to go abroad, but he failed in the end (CAS Archives, 1959b).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research,authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Notes

1.See ‘Diary from 1 July 1955 to 31 July 1958 and income and expenditure from June 1955 to December 1960’ in the database of the Project on Collecting the Historical Data of Chinese Scientists’ Academic Life:Huang Pao-tung SG-002-026.Materials and data about Huang Pao-tung used in this paper are all from this source unless otherwise indicated.

2.On 25 May 1951, Huang was arrested by the US Citizenship and Immigration Service and sent to Ellis Island for his part in the work of the Association of Chinese Scientific Workers in the US.After several twists and turns, the United Board of Christian Colleges in China agreed to pay his bail of $1400, but Huang had to repay $100 a month after he got a job.On 2 February 1955, the board returned the $1400 bail to Huang (see Wang and Zhang, 2018).

3.‘Wage point’ was a temporary wage system introduced in the early years of the PRC to cope with different local prices, and it was abolished in 1955.In 1955, each wage point was about 0.22yuan(see Shanghai Archives, 1955).

4.In his 1968 account, Huang wrote that one of the reasons for entering CIAC was his willingness to obey the government’s assignment and unwillingness to offend the leadership (although Feng Zhiliu wanted him to go to the East China Textile Institute in Shanghai or the Beijing Textile Research Institute).From the Project on Collecting the Historical Data of Chinese Scientists’ Academic Life: Huang Pao-tung SG-021-114-250.

5.From the Project on Collecting the Historical Data of Chinese Scientists’ Academic Life: Huang Pao-tung SG-003-034-045.

- 科學(xué)文化(英文)的其它文章

- Born to do science? A case study of family factors in the academic lives of the Chinese scientific elite

- Science and national defence:Special editions on the National Defence Science Movement during the Anti-Japanese War

- From ‘the mind isolated with the body’ to ‘the mind being embodied’:Contemporary approaches to the philosophy of the body

- Collecting and compiling the oral accounts of Chinese scientists trained in the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s: Practice and reflection

- The ‘neglected’ chemistry: Fuels and materials preparation in China’s ‘two bombs and one satellite’ project

- Introduction: One hundred years of striving—Chinese scientists in the 20th century