Surveillance and diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma:A systematic review

Sonia Pascual, Cayetano Miralles, Juan M Bernabé, Javier Irurzun, Mariana Planells

Abstract

Key words: Surveillance; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Ultrasonography; Cirrhosis; Imaging diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Primary liver cancer is the 6thmost commonly diagnosed cancer and was the 4hcause of cancer death worldwide in 2018, including hepatocellular carcinoma (75%-85%)and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (10%-15%)[1].In 2018, 841,080 new cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were diagnosed (4.7% of all new cases of cancer) and 781,631 patients died of this disease.It is more common in men and is currently the 2ndleading cause of cancer death worldwide in men and the 6thin women[2].According to data from the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, the 5-year survival for liver cancer is only 18%[3].

Incidence, mean age at diagnosis, and risk factors for HCC vary regionally according to the prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV)[4,5].However, the increasing incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in high socioeconomic countries, the viral load suppression with chronic antiviral treatment of HBV, the high rates of HCV curation with the new direct-acting antiviral(DAA) therapy as well as HBV vaccination programs could change this paradigm in the next decades[6].

The improvement in cirrhotic patient care and better management of clinical complications associated with chronic liver disease in the last years has led to a sustained decrease in mortality, and currently HCC development is the most severe and life threatening complication in these patients[7-9].Consequently, any action carried out to improve the prognosis of patients with end stage liver disease, must take into account early diagnosis of this cancer.In fact, HCC accomplishes the recommendation for surveillance programs established by the World Health Organization:it is an important health problem with high morbidity and mortality.The target population is clearly defined, the diagnosis test is easy to apply and there is a well-designed and accepted diagnosis process.Also, the diagnosis in early stages of the tumor allows access to curative treatment and a better prognosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this first part of the chapter, we review the evidence available on surveillance of HCC in patients with chronic liver disease according to the etiology and fibrosis status, the cost-effectiveness of such programs, and the impact in survival of surveillance.In the second part of the article, we review the diagnosis tools in these patients.

The review was conducted using the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews guidelines.A computer-aided systematic literature search of PubMed and Scopus databases was performed.This review has been divided into two different parts:screening and diagnosis.The development of this article was conducted by members of the multidisciplinary team for diagnosis and evaluation of HCC at our hospital (two hepatologists and three radiologists).The literature search was carried out by each author according to the part of the paper assigned to each physician.The combination of keywords in the first part were as follows:“Screening AND/OR Surveillance AND Hepatocellular Carcinoma” and for the second part:“Diagnosis AND Hepatocellular Carcinoma AND LIRADS”.In addition, the references of the more relevant studies (excluding case reports and articles in non-English languages)and specially the review and meta-analysis articles were manually searched to identify additional studies not detected in the previous selection.

In the first step, the title and abstract of each identified record was screened in order to explore the accuracy of the search and select only those really related to the topics.After this, the final list of selected articles was retrieved as full text for detailed assessment.

According to the topic assigned to each author, the most appropriate studies were selected to carry out the specific part of the review.

RESULTS

Survival advantages of surveillance diagnosis

The efficacy of any medical procedure should be based on objective data extracted from randomized and controlled studies.In the case of the hypothetical efficacy of surveillance programs in HCC, only two studies have assessed this aspect, both performed in Asia, and both in carriers of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).In the first, the screening test used was the determination of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) every 6 mo in the study group (n =3712)versusa control group without follow-up (n =1869).Despite earlier diagnosis in the screening group, there were no differences in 5-year survival between the groups[10].

In the latter study, in the screening group (n =9373), an ultrasonography (US)performed as well as an AFP have been performed every 6 mo comparing with control group without intervention (n =9373).Despite a low adherence of 60%, it showed an improvement in survival in the screening group, achieving a reduction in mortality to approximately 37%[11].

To date, no other study carried out in this context (Asian HBsAg-carrying patients)has evaluated the profitability of screening and therefore, these data have not been able to be extrapolated to other populations (e.g., western countries), as in other causes of chronic liver disease.This could be explained because the approach of a study of these characteristics (surveillancevsno surveillance) faces the refusal of the patients to sign an informed consent that includes the possibility of being part of the control group, as has been described in an article published a few years ago[12].

Given the absence of evidence with prospective series, several studies have tried to demonstrate the effectiveness of screening indirectly.American series reported that surveillance is associated with improved early stage detection, curative treatments and survival, despite adherence rates as low as less than 20%[13,14].A recent metaanalysis of studies published between 1990 and 2014, including abstracts presented in congresses from 2009 to 2012, identified a total of 45 original articles (most of them retrospective,n =38) that included a total of 15,158 patients with HCC, of which 41%had been diagnosed in screening programs.In most of the studies, the surveillance test employed was a combination of US and AFP (n =39) and was conducted in Europe (n =13), America (n =15), and Asia (n =15).This meta-analysis confirmed that these patients had tumors diagnosed in earlier stages of the disease, with greater possibility of curative treatment and better survival[15].

It must be taken into account that observational studies, especially in the setting of screening tools, have important bias that can confound assessment of screening test efficacy, that include lead-time bias (apparent improving survival because of an anticipated diagnosis), that can be minimized using correction formulas and length time bias (overrepresentation of slower growing tumors), that is inherent to this kind of study.

Based on the available evidence, the last published clinical practice guidelines from AASLD and EASL recommend the conduct of surveillance in patients with liver cirrhosis, with a moderate evidence level and a strong recommendation[16,17].

A more recent meta-analysis published in 2018, which included 19511 patients from 22 studies, showed an overall real world adherence rate to HCC surveillance imaging every 6-12 mo in 52%, better than previously reported[18].The authors observed that the prospective studies had an adherence rate of 71%, when compared with 39% of retrospective studies, suggesting that being aware of surveillance may have a positive effect on adherence rates.On the other hand, they did not identify any other factor related to HCC adherence (geographical area, etiology of liver disease, surveillance test or interval).Nevertheless, another study comparing HCC survival in Japan (with intensive national surveillance program,n =1174)versusHong Kong (none program,n =1675) over similar time periods (Japan 2000–2013, Hong Kong, China 2003–2014)showed that in Japan over 75% of cases are currently detected by surveillance,whereas in Hong Kong less than 20%.Median survival was 52 mo in Japan and 17.8 mo in Hong Kong; this survival advantage persisted after allowance for lead-time bias.A total of 63% of Japanese patients had early disease at diagnosis and 63%received curative treatmentversus31.7% and 44.1%, respectively in Hong-Kong.This suggests a clear benefit of the surveillance program[19].

In United States population, (a country where surveillance remains controversial),in real world, a matched case-control study carried out in the Veterans Affairs health care system, surveillance with ultrasound (US) and AFP was not associated with decreased HCC-related mortality[20].

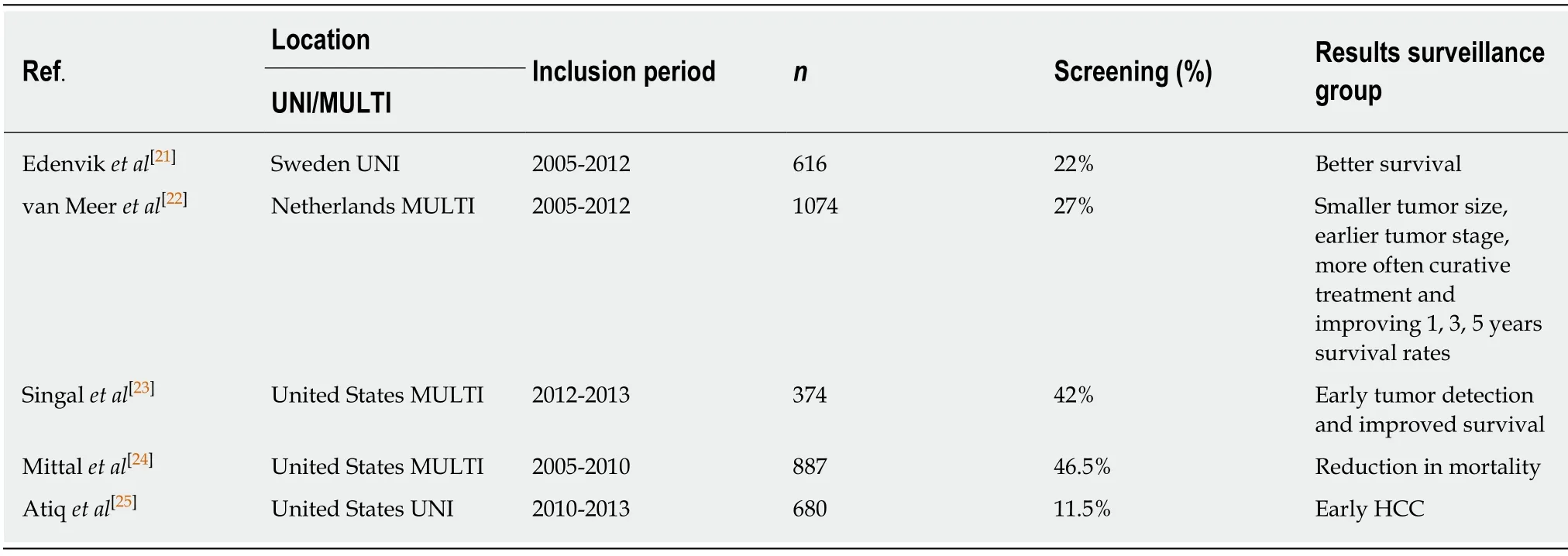

Table 1 summarizes the more recent, retrospective studies, published in the last years about surveillance of HCC in real life, and not included in previous metanalyses.As shown in the table, surveillance adherence remains low, both in Europe and the United States.

Cost-effectiveness of surveillance programs

As we have explained, HCC is a potential target for cancer surveillance as it occurs in well-defined at-risk populations, and curative therapy is possible when small tumors are diagnosed.Surveillance has been recommended by regional and national liver societies all over the world and is practiced widely.However, there is a lack of randomized controlled trials in real settings that could help to address the incidence from which the surveillance should be applied because it is the key parameter which determines the cost-effectiveness of HCC screening[26].

Most studies use decision models (Markov chain or decision tree), which usually include the full economic evaluation of HCC screening programs, a comparison between HCC techniques, and the outcome measures expressed in terms of quality adjusted life years[27-32].In general, a screening strategy is likely to be cost-effective in every setting considered, and a semiannual surveillance has been shown to be the most cost effective timing strategy.

Discrepancies in the results exist when determining the type of technology to be used.US alone or in association with AFP technology is likely to be the most costeffective, and the use of computed tomography (CT) shows controversial results.Screening should be implemented to detect HCC at an early stage of cirrhosis and is likely not cost-effective in advanced HCC or after liver transplantation[33].

Optimal surveillance interval

The interval between screening examinations for HCC has been established based on both the tumor growth rate and the tumor incidence in the target population and its cost-effectiveness[17].In studies carried out on the growth rate of untreated HCC, the time of duplication of tumor size is variable depending on factors such as their degree of differentiation[34].Currently, the recommended interval between scans for screening is 6 mo.This strategy increases the detection of small size lesions compared with the annual screening, in which curative treatments can be applied more frequently with greater patient survival, and has proved to be cost-effective[27,35].It does not seem that shortening to 3-mo screening interval improves the detection rate of small HCC(candidates for more radical treatments) or that it has an impact on survival over screening every 6 mo[36].

Surveillance tools

HCC screening includes imaging techniques and biomarkers.

Radiological:US:It is the most used test for the screening of HCC due to its wide availability, non-invasiveness, acceptable diagnostic accuracy, and cost.In addition,US provides additional information useful for the monitoring and assessment of the cirrhotic patient such as the appearance of ascites and portal thrombosis, but has the limitation of being an operator-dependent technique.Although it is difficult to establish its sensitivity and specificity due to the heterogeneity of the studies and their limitations, a meta-analysis that included 13 studies and 3571 patients found asensitivity and specificity of 94% for the detection of HCC[37].However, this sensitivity is lower (63%) when it comes to lesions in early stages.Sensitivity of US can be affected by certain conditions such as obesity, the presence of ascites, or very advanced liver disease, so in some cases it may be necessary to use alternative techniques[38].

Table 1 Studies about the advantages and results of surveillance in HCC

CT and magnetic resonance imaging:They are useful for the diagnosis of liver lesions, but in terms of screening tests, they are not cost-effective.Although these are more sensitive tests for the detection of lesions, especially in early stages, this greater sensitivity does not justify in most cases the increase in cost[27].It does not seem that annual CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferable to US every 6 mo given the estimated doubling time of HCC.Apart from the cost, there are other disadvantages in these techniques that limit their usefulness as screening tests such as radiation, the risk of nephrotoxicity, allergic reactions by CT contrast, the availability of MRI equipment in some centers, the duration of the MR as well as the discomfort and the use of contrasts with gadolinium.However, in patients in whom US assessment is difficult and may have a low sensitivity, the benefit of using alternative techniques such as CT or MRI and as well as its periodicity should be individualized.

Biomarkers:Serum biomarkers cannot be used alone for HCC surveillance because of their relatively low sensitivity and specificity.However, combined with imaging techniques, they can increase the sensitivity although this increases false-positive results.

AFP:It is the most studied biomarker of HCC.A positive result is considered to be higher than 20 ng/mL, although with these values it has a relatively low specificity and with levels above 200 ng/mL the technique has a high specificity, but a low sensitivity.According to the results of some studies, adding the determination of AFP to the imaging controls could increase the sensitivity to an additional 6%-8% of in the detection of HCC in in early stages, at the expense of slightly decreasing the specificity[39,40].This low yield of AFP is due to the fact that in certain chronic liver diseases, altered levels of this molecule can be observed without relation to HCC and only 10%-20% of HCC in initial stages has high values[17].In addition, adding AFP to US significantly increases the cost of screening[27].For all these reasons, a categorical recommendation of adding AFP to the imaging test cannot be established.

Although studies that demonstrate an increase in survival with the addition of AFP are lacking, since it could improve the detection of early lesions (and therefore susceptible to a more radical treatment) and the fact that a progressive increase in this determination in semi-annual controls may increase the suspicion of HCC, the decision to add AFP to imaging tests should be individualized[39].

Currently, the main guidelines do not establish a clear recommendation on its use.While the EASL guide does not recommend adding AFP to image screening, the AASLD guideline recommends screening with or without AFP along with the semester imaging test, so its use should be individualized[16,17].

Other biomarkers:There are other markers, des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin (DCP),the ratio of glycosylated AFP (L3 fraction) to total AFP and others, but for now they cannot be recommended as a screening technique.DCP and AFP-L3 have been associated with advanced HCC and portal vein invasion, but currently cannot be recommended as a screening technique, because none of them have been adequately studied as surveillance tests[17].

Populations

Screening should be performed in populations considered to be high risk.It is established that screening is cost-efficient in cirrhotic patients with a risk of developing HCC of 1.5% per year or more and in non-cirrhotic HBV patients with a risk of 0.2% per year or more[17].There are populations whose risk is not clearly established, such as non-cirrhotic NASH patients or patients with HCV who have reached a sustained viral response.

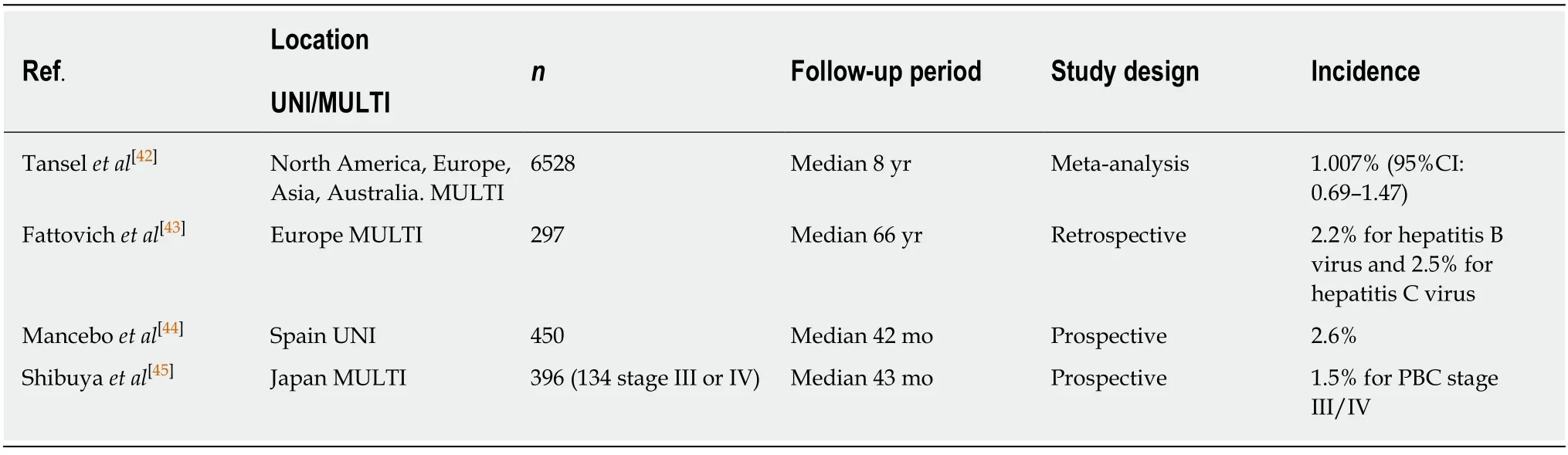

Cirrhosis/advanced fibrosis:Almost 80% of HCC develop on cirrhotic livers by any etiology.The studies carried out suggest a cost-effective screening for cirrhotic patients with a risk of developing HCC of 1.5% per year or more.This risk is equal or greater in cirrhotic patients by any etiology, in which this strategy would be beneficial.There are diseases such as cirrhosis of autoimmune origin in which although in several studies the incidence of HCC is less than 1.5% per year, a metaanalysis that included more than 6,000 patients obtained an annual incidence of 1.007%, but the 95% confidence interval (CI) was up to 1.47% per year[41,42].Table 2 shows the observed incidences of HCC according to their etiology.

In patients with advanced liver disease (Child C or Child B patients with massive ascites or deep jaundice), who are not candidates for a liver transplant, screening is not cost-effective since due to their clinical situation, they would not benefit from HCC treatment[17,46].

In the case of patients included in the waiting list for liver transplantation,screening for HCC should still be carried out even if they have a decompensated disease since the HCC can alter their position on list or exclude them in the case of exceeding the accepted criteria for transplant.

Regarding the age of the patient, there are no data to support interrupting the screening at a certain age, but this decision would be given by the patient's clinical situation, their life expectancy and comorbidities that may prevent a treatment of HCC.

In patients with fibrosis grade 3, for any etiology, screening is also recommended,although in some of these groups the benefit and its cost-effectiveness are still unclear and need further studies[17].

NAFLD:NAFLD is a cause of liver disease that is gaining prominence given the growing number of cases diagnosed, especially in industrialized countries[47].The natural history of HCC in patients with NAFLD and its pathogenesis is not known,although some theories involving proinflammatory cytokines, lipotoxicity, certain genetic polymorphisms in genes such asPNPLA3andMBOAT7, alterations in the microbiota, and possible increased absorption of iron have been discussed[48-50].Although the risk of developing HCC is greater in those with a cirrhotic liver, this disease poses an increased risk of developing HCC even in non-cirrhotic patients[51].In fact, a recent meta-analysis that included 168571 patients (13345 of them NASH)concluded that the risk of HCC in non-cirrhotic patients with NASH liver disease is 2.5 times higher than that in other etiologies[52].These results should be interpreted with caution given the heterogeneity of the studies included in the meta-analysis and the lack of data on the degree of fibrosis.However, given the large number of patients included, it is a relevant result.

Some studies have suggested that the diagnosis is later than in other etiologies due to possible underdiagnosis of conditions that increase the risk of HCC such as cirrhosis and also due to the greater difficulty in interpreting US, because of the attenuation of the US by subcutaneous fat, and the difficulty of obtaining images of the entire liver[38,51].Therefore, US has lower sensitivity for the detection of smaller tumors and in some series the prognosis could be worse.Although HCC may occur in patients with NAFLD in the absence of cirrhosis with a higher risk than in other etiologies, there is a lack of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of screening, which is why it is currently recommended in patients with cirrhosis or fibrosis 3 (advanced fibrosis can be diagnosed by elastography or by scoring systems like FIB-4), although it is based on expert opinions[53].

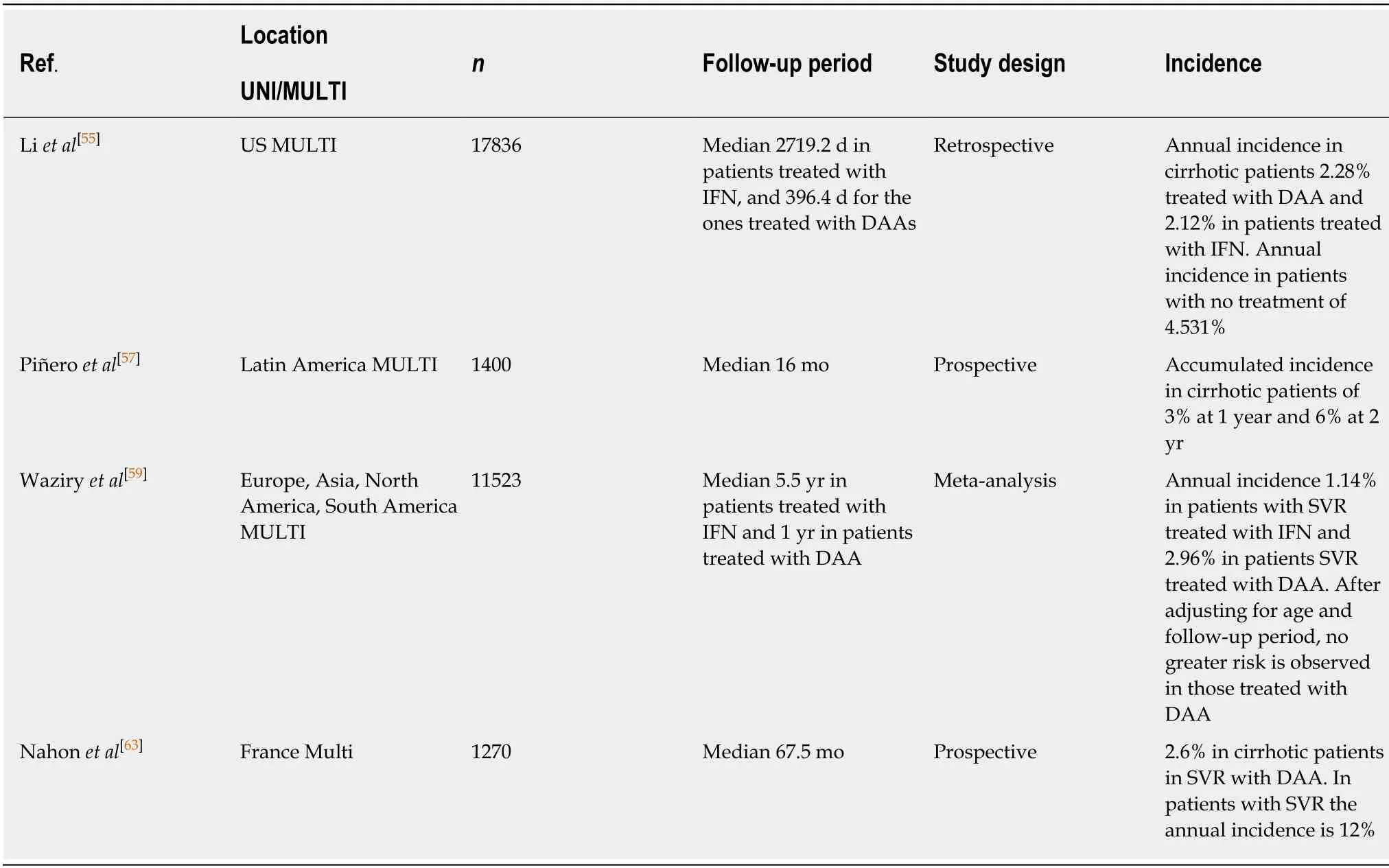

HCV:HCV is a risk factor for the development of cirrhosis and HCC.Achieving sustained viral response with interferon-based regimens has shown to be beneficial and reduce the risk of development of HCC for all degrees of fibrosis[54].With the recent regimens based on direct-acting antivirals, sustained viral response rates are higher than with the interferon-based regimens and achieve a reduction in the risk of suffering HCC of more than 70%[55-57].However, in some groups of patients, there isevidence to suggest that there may be a relationship between the use of DAA and early development of HCC after treatment.In these studies, risk factors have been identified, including the presence of non-characterizable nodules in cirrhotic patients prior to treatment initiation in which the response rate is 2.83 (95%CI:1.55, 5.16)compared to those without nodules or with benign nodules[58].This possibility makes adequate compliance in screening especially important in these patients.Other studies have also shown a higher incidence of HCC de novo in patients treated with DAAversusIFN.This may be due to the fact that treatments based on DAA are used in older patients with more advanced liver disease, so after adjusting the incidence for these risk factors, patients treated with DAA that reach sustained viral response (SVR)present no greater risk of HCC than those treated with IFN[59].

Table 2 Annual incidence of HCC in cirrhotic patients by etiology

Hepatitis treatment aims to reduce the risk of developing HCC, although it does not diminish completely[60].The risk is present especially in cirrhotic patients,although patients with fibrosis grade 3 also continue to present an increased risk, so the screening should be performed every 6 mo[57].There are several reasons that could justify this, such as an underestimation of the degree of fibrosis due to causes such as"sampling error" in the case of biopsies due to the size of the sample.In addition, it is important to note that after reaching the sustained viral response, the diagnostic accuracy of the elastographic techniques changes and can also underestimate fibrosis,so with the current evidence these techniques cannot be recommended in patients on SVR to decide on the need for screening[61,62].For this reason and although after the SVR it seems that there may be a reduction in fibrosis, these results should be interpreted with caution since this reduction may be overestimated by elastographic techniques and there are also a lack of data that correlates the reduction of fibrosis after SVR with a risk reduction that would allow interrupting the screening; so the current recommendation is to continue performing lifelong screening for fibrosis 3 and cirrhotic patients according to the pre-treatment fibrosis assessment despite a reduction in elastographic measures after achieving SVR[16,17].Table 3 shows the most recent studies and meta-analysis with the incidence of de novo HCC in patients treated with DAA.

HBV:HBV is associated with HCC even in non-cirrhotic patients (30% of the HCCs associated with HBV occur in these patients).This is due to the ability of viral DNA to integrate into host cells and act as a mutagenic agent.Therefore, although the presence of liver cirrhosis is the major risk factor in these patients, presenting a chronic B virus infection already constitutes an increased risk to develop HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.The incidence of HCC in non-cirrhotic HBV patients ranges from 0.1% to 0.8% per year and in cirrhotic patients from 2.2% to 4.3% per year[16,17].

In non-cirrhotic patients with HBV, the recommendation is established when the risk of developing HCC is 0.2% per year.This is because non-cirrhotic patients diagnosed with early-stage HCC are better candidates for radical treatments (such as surgery), so the cost-benefit of screening is different to cirrhotic patients in whom the liver function can limit the applicability of some treatments and therefore the annual incidence threshold to initiate screening in this group is lower[17].

The AASLD guide establishes populations at risk of HCC that require screening of cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic HBV patients with the following characteristics[16,64]:(1)High-risk HBsAg patients including African or Asian men (these ethnic groups have an increased risk of HCC older than 40 years and Asian women older than 50 years[65,66].(2) Patients with first-degree relatives diagnosed with HCC.(3) Patients with delta virus.(4) It is difficult to establish the risk in children and adolescents, butit seems reasonable to recommend screening patients with fibrosis grade 3 or cirrhosis and patients with first-degree relatives diagnosed with HCC.

Table 3 Annual HCC incidence in cirrhotic patients with HCV

In addition, predictive models have been proposed to assess the risk of HCC such as REACH-B and PAGE-B (in Caucasian patients on antiviral treatment), based on risk factors (viral load, male sex, age,etc).These models stratify HCC risk in at least three groups:low, intermediate, and high risk groups.Patients in the PAGE-B risk class have less than the 0.2%/year risk for HCC[67,68].Although the use of these scores has some limitations and cannot be universally applied, they can be useful to assess the need for antiviral treatment in certain cases or to assist in the decision to initiate HCC screening in patients who do not belong to the groups indicated.

Alcohol:Alcohol, due to its genotoxicity is directly related to the development of HCC, although it seems that this role is entirely due to the development of cirrhosis in patients without other etiological factors[17,69,70].Therefore, there is currently no recommendation on screening in patients with alcohol abuse who do not have advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis.However, it is relatively frequent that alcohol is not presented as the only cause of liver disease, but as an added factor to other etiologies such as viral hepatitis.In these patients, the sum of risk factors such as the consumption of large amounts of alcohol and others such as diabetes could increase the risk of HCC[71-73].It will be necessary in the future to identify the role that these etiological factors play in order to decide to initiate a screening program in noncirrhotic patients.

Other etiologies:In other pathologies such as primary biliary cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis, although the evidence is limited, screening does not seem beneficial if they do not present cirrhosis[17].

DISCUSSION

Imaging diagnosis

All current guidelines on the management of HCC accept that this tumor can only be diagnosed by means of imaging techniques if the lesion meets specific criteria and if it is a patient at risk for developing this neoplasm.If both conditions are not met, the biopsy will be necessary for the diagnosis[16,17,74].

The typical scenario is usually a lesion detected by surveillance US in a patient with liver disease, or a casual finding in imaging techniques that initially had another objective (being the liver disease previously known, or discovered at that time).

Characterization by means of imaging tests is based on the fact that HCC has specific vascular characteristics that reflect the results of the process of hepatocarcinogenesis:there is an increase in arterial supply and a decrease in portal vein branches.In a multiphasic study (CT or MRI), this means that a nodule will show greater vascularization in the arterial phase than the rest of the parenchyma, whereas in venous phases the opposite will occur, presenting lower contrast uptake than the surrounding liver[75-78].Demonstrating this behavior in a lesion of at least 1 cm,identified in a patient at risk, is diagnostic of HCC with values of specificity and positive predictive value that approach 100%[79-82].Sensitivity values are variable,depending on several factors, largely on the size of the lesion (for lesions between 1 and 2 cm, they are about 60%, increasing these values with lesion size)[78].For nodule(s) < 1 cm the specificity is lower, because even benign entities as arteriovenous fistula can have the same appearance.Therefore a close follow-up with US at 4-mo intervals is recommended.If the lesion remains stable for 12 mo, can return to regular surveillance (US every 6 mo)[17].

When the previous conditions are met for the diagnosis of HCC, biopsy is not considered necessary, since it will not improve the accuracy of the imaging tests.In addition, the biopsy can have diagnostic limitations (false negatives due to error in the sample or complicated differentiation between dysplasiavscarcinoma), technical difficulties for the procedure (obesity, ascites, location of the tumor that makes access difficult) and, above all potential complications because it is an invasive technique like bleeding or dissemination of the disease[79].

Currently, the imaging techniques validated for the diagnosis of HCC are multiphasic studies using CT and MRI.This conditions a maximum demand on the image, since not only is demanded to detect a lesion, but the objective is to characterize it.Therefore, in these cases it is essential to define quality criteria related to the technique itself, so that in concluding that a lesion "does not meet HCC criteria,"we can be sure that the study by image cannot reach the diagnosis.This avoids, for example, indicating a biopsy without being sure of having exhausted the non-invasive diagnostic path or ceasing to diagnose an injury that, depending on the context, can change the patient's management in a crucial way.

As for purely technical requirements, both CT and MRI are described in the LIRADS guidelines and the OPTN/UNOS has also published similar standards[83,84].These recommendations are in line with the current availability of techniques in the vast majority of centers (for example, it is suggested as a minimum, a multidetector CT of at least eight rows of detectors, and a MRI with 1.5 Tesla).

The intravenous contrast should be administered in a suitable dose, adapted to each patient and in CT the injection rate should be high whenever possible(recommended at least 4 mL/s).Regarding the phases to be performed, three are essential in CT (late arterial, portal and delayed phase) and in MRI the precontrast phase must be added (which is optional in CT, unless previous treatments have been performed that have used radiopaque contrast agents like Lipiodol?).Lesions in MRI are intrinsically T1 hyperintense lesions, due to the presence of elements like proteins,hemoglobin degradation products, copper or melanine, in which visual determination of hyperintensity attributable to contrast enhancement can be difficult; so precontrast imaging provides a baseline against which this enhancement can be identified and allows for subtraction imaging if necessary.

MRI provides the availability of numerous additional sequences unlike CT, which can provide more information.

The review of the quality of the images in the dynamic study is essential, which are similar in CT and MRI, whose compliance ensures that the images have been obtained at the optimum moment of hepatic vascularization.

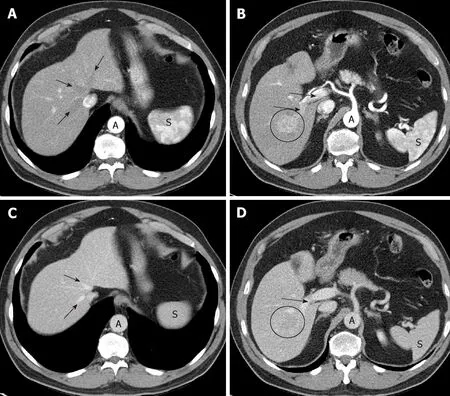

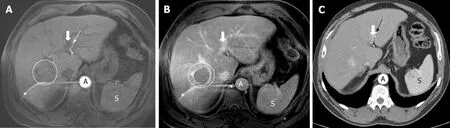

Late arterial phase:The hepatic arterial branches have to show an intense and homogeneous enhancement (which is especially guaranteed with a high flow rate of intravenous contrast injection on CT); in the portal vein the enhancement must be starting, but with non-opacified suprahepatic veins (Figure 1A,B).These three conditions indicate that the phase is adequate, allowing time for the hypervascular lesion to become opaque, but without there being a hepatic venous return.For an optimal moment of image acquisition, it is recommended to use automatic contrast detection techniques -bolus tracking or bolus test-, which adapt the phases to the cardiac output of each patient.

Figure 1 Optimal late arterial phase and portal phase.

If the portal vein still does not show contrast, we are in an early arterial phase,much less sensitive to detect HCC (Figure 2).On the other hand, if the suprahepatic veins are opacified by hepatic anterograde flow (not by retrograde contrast flow from the right atrium), it will be too late of a phase.In both cases, the exploration will have lost the ability to detect a hypervascular lesion.

Portal phase:Maximum hepatic parenchymal and portal vein enhancement (mainly depend on an adequate dose of contrast) is given; the suprahepatic veins are opacified by anterograde flow (Figure 1C,D).In this case, what is of interest is the maximum density in the hepatic parenchyma, which will make more evident the differences between a focal lesion and the surrounding non-tumor tissue.

Late venous phase (also known as delayed or equilibrium phase):Obtained between 2 and 5 minutes after injection of the contrast, with which both the liver and the vessels will have a lower density than in the portal phase.

If the multiphasic study does not meet these quality criteria, the next step is to consider whether the study is repeated or an alternative imaging technique is needed.

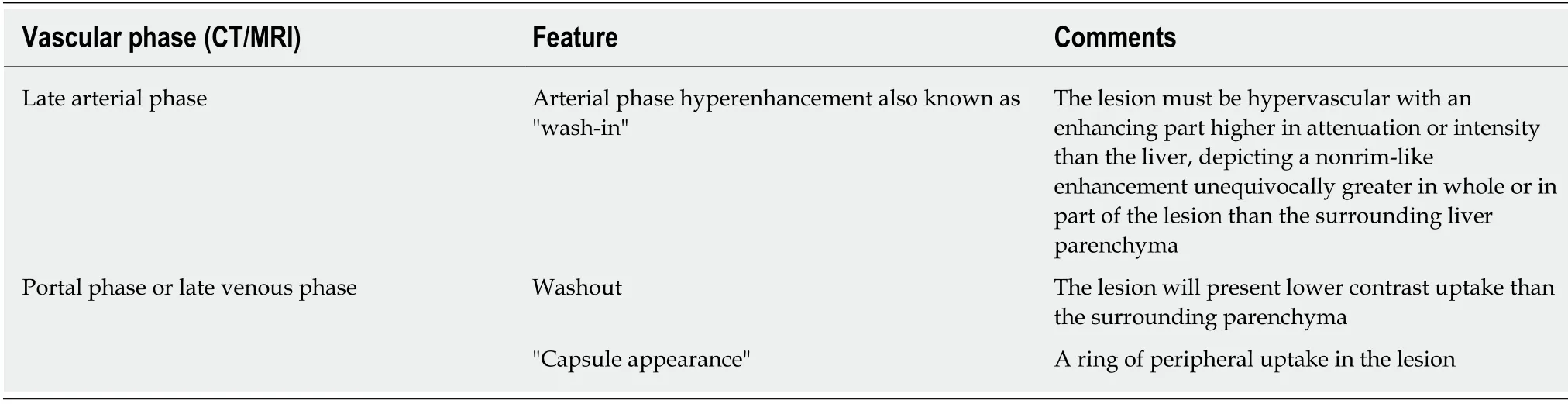

Once the imaging technique is considered valid, the behavior of the lesion in the different phases is assessed to determine if it meets diagnostic criteria for HCC, which is applicable when it reaches at least 1 cm in maximum diameter.As previously stated, the behavior of HCC correlates with its vascular characteristics, and the diagnosis is based on the findings depicted in Table 4.

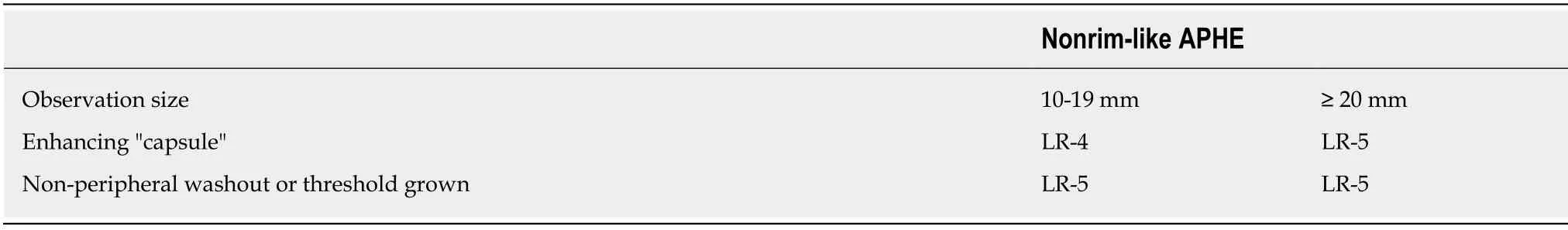

Demonstrating an arterial phase hyperenhancement (APHE) with washout in venous phases, allows the diagnosis of HCC (Figure 3).The LIRADS criteria give the presence of the "enhancing capsule" in nodules ≥ 20 mm the same value as the washout.The diagnosis of HCC is also considered as the growth of a hypervascular nodule by ≥ 50% of its diameter in ≤ 6 mo (Table 5).

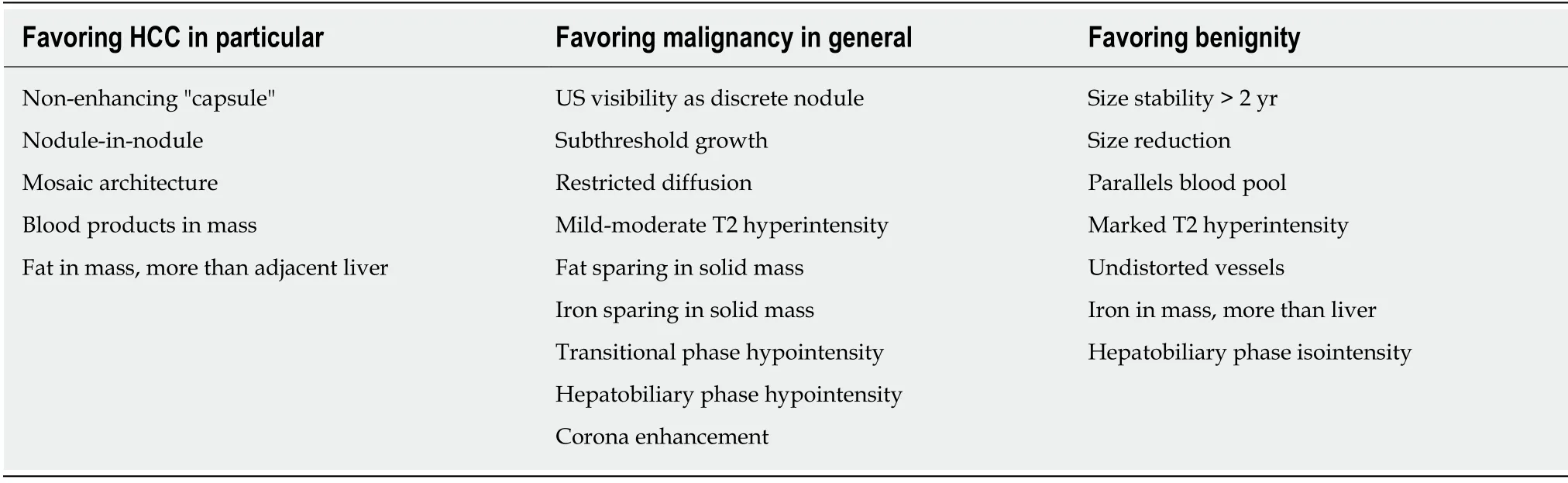

These are the only criteria that allow the diagnosis by image of HCC.Several"ancillary findings" are described, which can guide or increase the suspicion of HCC,but in no case establish a diagnosis, if the previously defined criteria are not met.Examples of these findings are outlined in Table 6.

Treated lesions have special considerations at LIRADS classification, establishing 3 categories known as nonviable, equivocal or viable.Viable tissue after treatment is considered when APHE, washout or similar pretreatment enhancement is seen.Multidisciplinary discussion for consensus management is mandatory in these patients.

Figure 2 lmportance of precise late arterial phase.

Hepatospecific contrasts

Hepatobiliary agents in MRI are a type of intravenous contrast with dual properties:on one hand it has an initial extracellular distribution, so that, like the rest of contrasts, it allows to assess the vascularization of the lesion; on the other, it is captured and excreted by the hepatocyte, in a different proportion:Gadoxetate disodium has 50% uptake and hepatobiliary elimination, while in Gadobenate dimeglumine it has a 5% hepatobiliary elimination (the rest in both has a renal elimination).Its application in patients with suspected HCC is also based on the process of hepatocarcinogenesis:the evolution from regeneration nodule to HCC,there is a decrease in hepatocyte capacity for uptake and elimination of the bile duct of hepatospecific contrast due to alterations in membrane transporters[75,76,85].Thus,when images of the liver are obtained at the moment when the peak of contrast uptake by the hepatocyte exists (after 20 min for the Gadoxetic and around 60 min for the Gadobenate), the non-tumor parenchyma should show enhancement, while most HCCs will show low signal intensity, as will any other lesion that does not have functioning hepatocytes (for example, benign lesions such as a cyst or a hemangioma,or malignant lesions, such as a metastasis).

The use of this type of contrast may increase the sensitivity and the negative predictive value, but it does not improve the specificity and is still considered an"ancillary finding" without constituting a major criteria for the diagnosis of HCC[17].

CEUS

The US contrast is based on microbubbles, and has a purely intravascular distribution,without passage to the interstitium, which results in a lesion behavior somewhat different to that seen in iodinated contrast media for CT and in extracellular gadolinium-based media for MRI[86].This is especially important in cholangiocarcinoma, which in CEUS may show homogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase, followed by rapid washing, so that this behavior would no longer be specific for HCC in this technique[87,88].It has been described as a differentiating factor between both entities that the HCC has an earlier enhancement and a less intense and later washing (> 60 s) than the cholangiocarcinoma[86,89].

The use is recommended only in centers with experience, being a highly operatordependent technique, less reproducible than CT or MRI, and serves for a targeted assessment of a lesion, without allowing a study of the entire liver.

Thus, CEUS is not suitable for screening or surveillance.Rather, it is used to characterize lesion(s) identified on a screening and surveillance US or on CT/MRI.It is not recommended as a first-line imaging technique, because CT or MRI will be needed for staging, but it can be utilized when both CT and MRI are contraindicated or are inconclusive for the HCC diagnosis[17].In this way, a CEUS LIRADS has also been developed[83].

CEUS is not only a valuable contributor to multimodality imaging for characterizing nodules in a cirrhotic liver, but may also be used, for example, to guide biopsy or treatment of lesions that are difficult to visualize with pre-contrast US, or to detect enhancement in a portal thrombus, in order to differentiate bland thrombus from neoplastic thrombosis[86].This differentiation takes on importance due to the increased incidence of non-neoplastic portal vein thrombosis[90].

TC versus RM

Table 4 Findings for HCC diagnosis

There are no conclusive studies demonstrating the superiority of one technique over another for the diagnosis of HCC, although the tendency is for a slight advantage of MRI, due to greater sensitivity, especially for small lesions (< 20 mm), and the MRI provides more information for ancillary findings, in addition to the added value of being able to use an hepatospecific contrast[16,17].

The choice between CT or MRI will depend to a great extent on other variables,beyond the diagnosis such as the availability of the technique, the radiologist's experience or certain characteristics of the patient like obesity, ascites or difficulty in performing apneas that can significantly limit the quality of the MR image, with CT being a more reliable technique in these circumstances.Claustrophobia can also prevent a patient from having an MRI.As for CT, it is necessary to take into account ionizing radiation (especially in young patients and multiphasic studies, which need several series) and allergy to iodinated contrast.Renal insufficiency limits the use of contrasts, both in CT and MRI, although patients in hemodialysis can have performed a CT scan, while MRI is contraindicated in this case because of the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis[16].

LI-RADS?

Standardized report and assessment by reference center and multidisciplinary committee.The introduction of LIRADS aims to achieve a standardized process that is part of the study by image of the patient at risk of developing HCC, from the technique of completion to the written report of the examination[83].

In each liver lesion detected, the size (larger diameter), the liver segment where it is located and the degree of suspicion of HCC should be described according to their behavior (Table 7).To determine the likelihood of HCC, the LI-RADS categories are suggested (from LI-RADS 1, corresponding to lesion with benign features, to LI-RADS 5, which is a lesion with diagnostic criteria for HCC).The intermediate categories (LIRADS 2, 3 and 4) refer to an increase in the probability of HCC, but without making it possible to achieve diagnostic imaging, so that management in these cases will always depend on a multidisciplinary and individualized assessment of each patient, being able to decide on options as different as a biopsy, to perform an alternative imaging technique as well as having a more or less narrow follow-up, or even a treatment[16].

The evaluation of imaging studies in a multidisciplinary committee and reference centers is recommended, which results in better results in diagnosis, management and even patient survival[16].

The last studies about regular surveillance of HCC in advanced liver diseases,suggest that it could be cost-beneficial in this context, although the evidence in clinical practice is still limited.US at 6-mo interval appears the most extending tool for surveillance and a CT and/or MRI are the most accepted imaging techniques for HCC diagnosis, relegating the biopsy procedure only for selected cases.Advances in HBV control viremia and HCV definitive curation is decreasing the HCC incidence.In the next decades, the high risk subgroups that will benefit from surveillance remains an important research goal in this new stage.

Table 5 Computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging diagnostic table

Table 6 Ancillary findings (LlRADS 2018)

Table 7 Ll-RADS 2018 recommendations for untreated ≥ 1 cm lesions without pathologic proof in patients at high risk for HCC

Figure 3 lmportance of delayed phase.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been proposed and recommended in clinical guidelines, in order to obtain earlier diagnosis but it is still controversial and it is not accepted worldwide.

Research motivation

Emerging populations like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients or hepatitis C virus (HCV)after achieving sustained viral response (SVR) are at risk of developing HCC.Should they be screened? What is the ideal screening tool attending cost-effectiveness?

Research objectives

Support the surveillance programs in patients at risk of developing HCC because of the costeffectiveness of early diagnosis.

Research methods

Systematic review of recent literature of surveillance (tools, interval, cost-benefit, target population) and the role of imaging diagnosis (radiological non-invasive diagnosis, optimal modality and agents) of HCC.

Research results

The benefits of surveillance of HCC, mainly with ultrasonography, have been assessed in several prospective and retrospective analysis.Surveillance of HCC permits diagnosis in early stages allowing better access to curative treatment and increased life expectancy in patients at risk.

Research conclusions

The actual evidence supports the recommendation of performing surveillance of HCC in patients with cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis of any etiology susceptible of treatment, using ultrasonography every 6 mo.In some populations of non-cirrhotic hepatitis B virus patients the screening can be cost-effective.The diagnosis evaluation of HCC can be established based on noninvasive imaging criteria in patients with cirrhosis.

Research perspectives

Further studies need for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of screening in emerging populations like non-cirrhotic non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients or HCV who achieved SVR.Utility of hepatospecific contrasts needs further evaluation.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年16期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年16期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Role of infrapatellar fat pad in pathological process of knee osteoarthritis:Future applications in treatment

- Application of Newcastle disease virus in the treatment of colorectal cancer

- Reduced microRNA-451 expression in eutopic endometrium contributes to the pathogenesis of endometriosis

- Application of self-care based on full-course individualized health education in patients with chronic heart failure and its influencing factors

- Predicting surgical site infections using a novel nomogram in patients with hepatocelluar carcinoma undergoing hepatectomy

- Serological investigation of lgG and lgE antibodies against food antigens in patients with inflammatory bowel disease