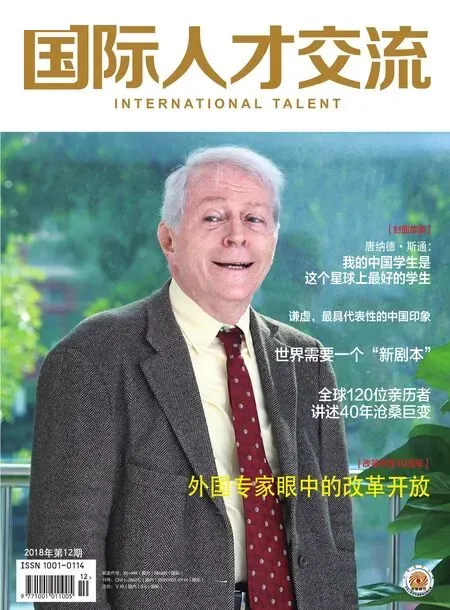

Professor Donald Stone: Experiencing China

By Donald Stone

In 2006, after having devoted nearly forty years to teaching English literature at the City University of New York, as well as Harvard University (as visiting professor) and New York University (as adjunct professor), I had the good fortune to be invited to teach in the English Department at Peking University.For four months of the year, I have taught the undergraduate English novels course (Jane Austen to James Joyce) plus a graduate course or seminar to, in my opinion, the best students on the planet. My Chinese students are not only, by and large,phenomenally intelligent, they are also full of imagination and fun. They are extraordinarily responsive and reflective. They know instinctively that a key to the understanding of life and literature is the capacity to empathize: to imagine oneself in the position of another person or another culture.

Isaiah Berlin, while not denying the differences between cultures, has asserted that “Members of one culture can by the force of imaginative insight, understand... the values, the ideals,the forms of life of another culture or society, even those remote in time or space”. Berlin speaks eloquently of cultural pluralism as the goal of the humanities: “Intercommunication between cultures in time and space is only possible because what makes men human is common to them, and acts as a bridge between them.” The themes contained in the books my Beida students read-whether positive values or negative warnings-are matters the students can readily recognize and respond to. The more they learn about “foreign” cultures, the more they learn about their own. This is what Hans-Georg Gadamer calls learning “to become at home” in the “other.”

From the moment that I first arrived in China, in the fall of 1982,I felt immediately that I had come home. I first came to China through the invitation of distinguished Professor Zhu Hong,who had, in 1980, been invited to Harvard as part of an exchange of scholars set up between the Chinese Academy of Social Science (where she was head of the English Literature division) and the National Academy of Science, Washington. For ten years, the two institutions arranged for the exchange of Chinese and American scholars. The late Professor Daniel Aaron was the first guest at CASS, and in 1991 I was asked to be the last American professor participating in this program. In 1982, I taught at Beijing Teachers College (now renamed Capital Normal University), where I encountered an astounding group of studentsthe famous class of 1977. Above all my student assistant, and subsequent Chinese brother, Wang Wei, who later served as vice president of China’s Olympic committee. (When China received the invitation to host the games, I was one of the first persons Wang Wei telephoned with the good news.) Another of my students, Sun Zhixin, currently serves as Brooke Russell Astor Curator of Chinese Art at the Metropolitan Museum, New York. In 2017 he organized the extraordinary exhibition-”Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties”-h(huán)eld first at the Met, and then at Beijing’s National Museum. In 1982 Zhixin not only took me through the Palace Museum collection, he also helped introduce me to contemporary Chinese painters such as Wu Guanzhong and Huang Yongyu. My love of art is as strong as my love of literature, and it became clear to me in 1982 that Chinese modern artists such as Qi Baishi, Fu Baoshi, Pan Tianshou, and Li Keran, were as great as their western counterparts,Picasso and Matisse.

China in 1982 was opening to the west, and my students were fascinated by western texts like George Eliot’s Middlemarch(which I helped introduce into the Chinese curriculum) and by films like “The Sound of Music.” I recall a performance of the song “Edelweiss” performed by a student group at Teachers College at a Christmas celebration given for the foreign teachers. They seemed especially moved when they sang the line,“Bless my homeland forever.” It was thanks to my love of Middlemarch that I became an English major and then a Victorianist scholar; but I have never encountered in America the kind of responsiveness which my Chinese students bring to that novel.The Victorian idea that one should devote oneself to others without expectation of recognition or reward invariably strikes a chord in my Chinese students. There is always a respectful silence when I read the book’s last paragraph:

(Dorothea Brook’s) finely-touched spirit had still its fine issues,even though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life and rest in unvisited tombs.

It is a remarkable tribute to the humanities, I think, that these words have such resonance in modern China. I had not anticipated the emotional nature of my students and, indeed,so many of the people that I met in China. Wang Wei once explained to me that Chinese people resemble the hutongs in which (in the 1980s) many of them lived. On the outside, he said,you see protective walls, but once you find the road leading into the collection of houses and courtyards, you find a vibrant community of people helping one another. Similarly, the teachers and students in a Chinese college form a kind of family. (As one of the oldest members of the Beida English Department, I am sometimes called “ye ye”—Grandpa—Stone by my students.) In practice, this means that Beida teachers are deeply concerned with the welfare and future of their students. And there is a collegiality between the members of the department of a kind rare outside of China.

Each fall when I return to my teaching post at Beida, I do so with the greatest of expectations and with the pride of someone possessing a Peking University identity card. Each time I show that card as I enter the East or West Gate to the college, I feel like one of the luckiest people alive; and I think most Beida students feel the same way. Having lectured at colleges from one end of the country to the other (including institutions in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macao), I have met extraordinary students everywhere; and I remember with particular delight the students from Tianshui University in Western Gansu province.These were students from peasant background, and I was one of the few American visitors to the college at the time (2004). I don’t think I will ever encounter a more motivated group of students. After my lecture, one of the students asked if I thought an American-style democracy would work in China, and I replied-to great laughter from the audience-that I often wished an American-style democracy would work in America. To be in contact with such students is a source of incredible happiness-but it is also a challenge. To teach the best, one must oneself do the best one can. Before teaching in 1982, I carefully reread every work on my reading list-King Lear, Paradise Lost, Pride and Prejudice, Great Expectations, etc-and I asked myself, “Are these works really so great that they deserve to be taught in a foreign language in a country with the oldest and greatest civilization known to mankind?” It was a very useful exercise, I found, because in the end I did come to the conclusion that Shakespeare and Milton and Austen and Dickens mattered-that teaching and reading the classic English texts in China (or America) was something truly worth doing.

When I began teaching at Beida in 2006, it was on an experimental basis: I wasn’t sure that I would have enough energy to teach more than a single semester. But I found myself so rejuvenated by the experience that I returned for a second year, and then a third-and now (as of this writing) I am preparing for my thirteenth (fall of 2018) ! During my first three years at Beida, I taught an ambitious class called “Aspects of Western Culture.”I had assumed that the English Department would want me to teach a survey of English literature class (similar to one I had taught at Beijing Teachers College in 1982), but in fact I was given carte blanche to teach whatever I wanted. This was something I had never been given the chance to do at CUNY, so I put together a syllabus that contained, among other things, Mozart operas (2006 marked the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth).slides of Rembrandt’s paintings (2006 was also the 400th anniversary of Rembrandt’s birth), videos of Shakespeare plays, a sampling of western movies (Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, Fellini’s 8 1/2, George Stevens’s Swing Time, Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries). I remember how the students, having just seen a video of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, burst into applause at the end. Most of them had heard about Mozart but had never actually seen or heard one of his operas. And I remember once, while teaching on December 25 (Christmas), I played excerpts from some of my favorite movie musicals-Gene Kelly singing and dancing in the rain, Judy Garland singing “Have yourself a merry little Christmas” (from Meet Me in St. Louis)-with tears running down my face. My Chinese students can be very emotional, and so too their teacher.

At the end of the first semester, I asked the students to write their term paper in the form of letters to me, explaining what there was to be learned from all these disparate Western artworks-an impossibly vague assignment, and yet the students wrote wonderful essays doing just that. In subsequent semesters I asked for more specific topics; and the results were even more wonderful. One student from Datong, Lu Wei, mentioned in his deeply moving paper how his mother had encouraged him to look at western art when he was young. Another student compared the theme of forgiveness in Shakespeare’s King Lear and Bergman’s Wild Strawberries. I was inspired by the latter paper to write a study of the theme of forgiveness in Western art and literature. 5 years later, I had the good fortune to read my essay in the presence of the student who had inspired my topic, Huang Zhongfeng. She was at this point a graduate student at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, where I had been invited to give this talk. Both Lu Wei and Zhongfeng are now college professors teaching in Beijing.

The interest of the graduate students in the Western writers,composers, and artists who were part of the “Western Culture”syllabus gave me two ideas. One was to set up a series of reading groups each fall in which, on several Fridays during the semester, we covered material that was not assigned in the regular curriculum. For example, one year I directed a reading group devoted to Victorian Poetry, which proved so popular(the students who faithfully attended and read the assignments received no academic credit) that eventually it became a graduate seminar, which I now teach every other year. Another year we examined British artists (Hogarth, Gainsborough, Turner,Lucian Freud, etc.) as well as British writers who wrote about art (Hazlitt, Ruskin, Pater, Henry James, etc.). For the Dickens bicentenary (2012) we looked at films based on the master’s novels. Perhaps the best-liked of all these film adaptations was the old 1935 A Tale of Two Cities, with Ronald Colman going to an emotionally charged death at the end. When the lights came back on at the end of the film, I noted that very few students in the audience were dry-eyed. Together with Barbara Rendall (the wife of my beloved Canadian colleague Tom Rendall), I offered an introduction to American popular culture of the 1960s in the form of selected episodes from the television series Mad Men.This allowed us to discuss some of the important events of the 60s (a time when China and America were cut off from one another), such as the death of President John F. Kennedy, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Women’s Rights Movement.

The second idea that came out of the “Western Culture” course was the prospect of holding exhibitions of Western art at the campus museum, named after its great benefactor Arthur M.Sackler. Mr. Sackler had created museums in Washington and at Harvard and elsewhere, and he wanted China’s most famous university to have an art museum. Outside China it is common for great universities to have an art museum, usually endowed by their alumni, but such a thing is a novelty in China. My first thought was that maybe I could persuade American museums to lend some of their artworks to Beida; but when that failed, I organized an exhibition in 2007 devoted to a set of lithographs by the French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix to illustrate Hamlet. Only eighty sets of the Hamlet prints were printed in the first edition in 1843, and I was proud that Beida owned these rare and beautiful works. Between 2007 and 2017 I have mounted eleven exhibitions for the museum, virtually everything (out of a current total of 558 prints and drawings) being my personal donations. As a lifelong art collector (albeit of modest means),I have been able to find notable artworks ranging from the Renaissance (engravings and woodcuts by or after Raphael, Titian,Dürer, Bruegel, etc) and continuing into the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries (four Rembrandts, twenty Rubenses, fifteen Hogarths,ten Piranesis, five Turners including two drawings, nearly eighty Daumiers). At last count, we had twenty-one Picassos,thirty Chagalls, ten Matisses, and eight Georges Braques. I am particularly proud of the 2017-2018 exhibition “Celebrating British Artists and British ‘Print Culture’ from Hogarth to Turner,” perhaps the most comprehensive show of its kind held anywhere. Putting these exhibitions together has been my way of thanking Beida and its students for making me feel at home here, and the response from the students has been very gratifying. To accompany these yearly exhibitions, I have recently created a series of talks dealing with Western art, presented from a very personal perspective. The talks are called “Cities of Art,”and in each one I introduce Beida students to a major Western city that not only contains great art but is itself a work of art. So far, I have taken them to Vienna, New York, Venice, Paris, and London. Berlin is the city chosen for the fall of 2018.

The experience of living and teaching in China has provided the greatest happiness of my life. It is a source of great pride that some of my scholarly writings have been translated into Chinese(an essay on Matthew Arnold in a volume published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, my chapter on Henry James for the Cambridge History of Literary Criticism, translated by Professor Dai Xianmei of Remnin University), and that my book on Arnold, which I dedicated to five Chinese friends (Zhu Hong,Han Zhixian, Yang Chuanwei, Wang Wei, and Huang Mei), is being translated for Nanjing University Press by Dr. Matthew Fan of the Science and Technology University. I am hugely and humbly proud of the honors generously given me: in 2011, a Certificate of Special Achievement Award from the Beijing Municipality for my “enthusiastic support and contribution to Beijing’s international cooperation and exchange in education”; and, in 2014, a National Friendship Award, the highest honor China’s gives to foreigners. In September 2014, I was one of 3500 guests in the Great Hall of the People, dining with President Xi Jinping and his two predecessors, Presidents Zhang Zemin and Hu Jintao.This was the proudest day of my life.

It is my fondest desire that Peking University-and other universities in China-encourages its students to learn from many sources, to become at home in as many cultures as possible. It has been China’s good fortune throughout her history to have learned from and to have absorbed so many cultures into her own. A species thrives (as Charles Darwin argued in The Origin of Species) from its ability to draw upon what other species have to offer. In the 21st century, we are witnessing the devastating results of civil wars, tribal hatreds, massive examples of intolerance. For those of us who teach the humanities-whether in the East or the West-the hope remains that fruitful “intercommunication between cultures” will continue to be a viable ideal and a potential reality.