Feasibility of personalized treatment concepts in gastrointestinal malignancies: Sub-group results of prospective clinical phase II trial EXACT

Matthias Unseld, Robert Mader, Lukas Baumann, Clarence Veraar, Fritz Wrba,Fredrik Waneck, Markus Kieler, Daniela Bianconi, Walter Berger, Maria Sibilia, Leonhard Müllauer, Christoph Zielinski, Gerald W. Prager

1Department of Medicine I, Division of Oncology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1090, Austria; 2Comprehensive Cancer Center, Medical University Vienna — General Hospital, Vienna 1090, Austria; 3Department of Medical Statistics, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1090, Austria; 4Clinical Institute of Pathology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1090, Austria; 5Department of Interventional Radiology,Medical University of Vienna, Vienna 1090, Austria; 6Department of Medicine I, Institute of Cancer Research, Medical University of Vienna,Vienna 1090, Austria

Abstract Objective: Advances in high-throughput genomic profiling and the development of new targeted therapies improve patient’s survival. In gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies, the concept of personalized medicine (PM) was not investigated so far. The aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the efficacy of a personalized treatment in GI patients who failed standard treatment.Methods: Out of the original prospective clinical phase II EXACT trial, 21 (38%) GI cancer patients who had no further treatment options were identified. A molecular profile (MP) via a 50 gene next generation sequencing(NGS) panel in combination with immunohistochemistry (IHC) was conducted using real-time biopsy tumor material. Results were discussed by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) to translate the individual MP in an experimental treatment.Results: Of the 55 patients originally included in the EXACT trial, 21 (38%) suffered from GI malignancies.The final analysis showed that 15 (71%) patients had experienced a longer progression-free survival (PFS) upon experimental targeted treatment (124 d, quartiles 70/193 d), when compared with the PFS achieved by the previous conventional therapy (62 d, quartiles 55/83 d) (P=0.014). Thirteen (62%) patients receiving targeted treatment experienced a disease control according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). Median overall survival (OS) from the start of experimental therapy to time of censoring or death was 193 d (quartiles 115/374 d).Conclusions: PM was not investigated in GI malignancies so far in a prospective trial. This study shows that treatment based on real-time molecular tumor profiling led to a superior clinical benefit, and survival as well as response was significantly improved when compared with previous standard medications.

Keywords: Personalized medicine; gastrointestinal malignancies; prospective trial; next generations sequencing

Introduction

Precision medicine utilizes molecular in formation to specify an individual disease and provide potential tailored treatment options (1). Progress in high-throughput technologies has led to the identification of multiple genomic alterations. In combination with the continuously development of new target therapies, precision medicine becomes compatible with the timeframe of clinical practice(2). Many genetic molecular alterations exist across different tumor types and histologies, thereby shifting the existing drug development strategies more and more towards a histology-agnostic molecularly based treatment(3). Some specific molecules have already proven their impact on cancer treatment considerations. This is best exemplified by the success of imatinib in chronic myelogenous leukemia (4). Since then, a number of early phase clinical trials tested targeted treatment in specific molecularly characterized subsets of patients (5-10). Those basket trials showed variable results and encouraged translational researchers to assess predictive biomarkers to determine outcome and efficacy. In gastric cancer,trastuzumab is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)approved targeted therapy for which a biomarker of response (HER2 amplification) is available (11). Other biomarkers influence anti-epidermal growth factor receptor(EGFR) therapy (RAS mutation) (12) or determine prognostic value (BRAF V600E mutation) (13). However,prospective randomized clinical trials are lacking which clarify whether matching actionable mutations with targeted therapy will contribute to improving survival in gastrointestinal (GI) cancer patients.

Here, we have examined the concept of precision medicine in GI malignancies by using molecular profiling of patients’ tumors in the era of molecularly targeted treatments as well as immunotherapies. We have demonstrated that in a majority of patients an individualized molecular targeted treatment, based on real-time assessment of the tumor’s molecular profile (MP), might reflect an efficient strategy to control the underlying disease and exceed the efficacy of the immediately preceding standard treatment administered.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethic Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (Nr.1541/2012). The study is registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (No. NCT02999750).

Study design

The study (Extended Analysis for Cancer Treatment-EXACT) was defined to prospectively validate treatment benefit of an individualized treatment concept based on the MP from paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections obtained before the start of treatment (real time biopsy).Here we aimed to evaluate the GI subgroup of the trial.The primary objective was to determine whether the individualized treatment concept resulted in a longer progression-free survival (PFS1) when compared with the last standard treatment given before (PFS0). Secondary endpoints consisted of assessment of overall treatment response rate (ORR) and overall survival (OS) by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria.

Patients

Patient eligibility criteria included informed consent, any histologic type of GI cancer without further standard treatment options according to international treatment guidelines, tumor progression upon treatment by RECIST criteria, age ≥18 years old, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0-1. A fresh tumor biopsy was obtained for pathologic analysis. Biopsies were performed by interventional radiological techniques.Patients were considered to be eligible for inclusion in the study if treatment could be initiated based upon the MP derived from cancers by real-time biopsy.

Individual treatment suggestions were derived from a molecular oncology tumor board. This multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting was held on a biweekly schedule.Results of the molecular characteristics were discussed and therapy was offered related to toxicity profiles, data derived from prospective clinical trials as well as respective patient history.

Cancer gene panel sequencing

The DNA library was generated by multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2TM(Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA,USA). The panel covers mutation hotspots of 50 genes,mostly oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that are frequently mutated in tumors (ABL,AKT,ALK,APC,ATM,BRAF,CDH,CDKN2A,CSF1R,CTNNB1,EGFR,ERBB2,

ERBB4,EZH2,FBXW7,FGFR1,FGFR2,FGFR3,FLT3,GNA11,GNAS,GNAQ,HNF1A,HRAS,IDH1,JAK2,JAK3,IDH2,KDR,KIT,KRAS,MET,MLH1,MPL,NOTCH1,NPM1,NRAS,PDGFRA,PIK3CA,PTEN,PTPN11,RB1,RET,SMAD4,SMARCB1,SMO,SRC,STK11,TP53,VHL).Sequencing was performed with an Ion Torrent PGMTM(Life Technologies). Ambiguous nonsynonymous mutations detected with the Ion Torrent PGMTMwere verified by capillary sequencing. The sequencing of PCR products was carried out with the BigDyeR Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham,MA, USA). The resulting DNA fragments were purified with the DyeEx 96 Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden,Germany) and sequenced with a 3500 Genetic Analyzer(Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham,MA, USA). For sequence analysis we employed the SeqScape Version 2.7 software (Applied Biosystems).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC was performed with a Ventana Benchmark Ultra stainer (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA). The following antibodies were employed: ALK (clone 1A4; Zytomed,Berlin, Germany), CD30 (clone BerH2; Dako, Vienna,Austria), CD20 (clone L26; Dako), EGFR (clone 3C6;Ventana), Estrogen-receptor (clone SP1; Ventana), HER2(clone 4B5; Ventana), HER3 (clone SP71; Abcam), KIT(clone 9.7; Ventana), MET (clone SP44; Ventana),phospho-mTOR (clone 49F9; Cell Signalling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), PDGFRA (rabbit polyclonal;Thermo Fisher Scientific), PDGFRB (clone 28E1, Cell Signalling), PD-L1 (clone E1L3N; Cell Signalling),Progesterone-receptor (clone 1E2; Ventana), PTEN (clone Y184; Abcam) and ROS1 (clone D4D6; Cell Signalling).

Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis on a difference between PFS0 and PFS1, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used. To find possible patient characteristics which could potentially influence the difference between PFS0 and PFS1, a linear model was performed with the difference (PFS1-PFS0) as dependent variables, and age as well as gender as independent variables. Furthermore, a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the median of the ratio PFS1/PFS0 was calculated through bootstrap with 1,000 samples. It has to be noted that three of the 55 patients had still an ongoing therapy at the time of the present analysis.Analysis was performed using statistical Software R(Version 3.3.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing,Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics and study algorithm

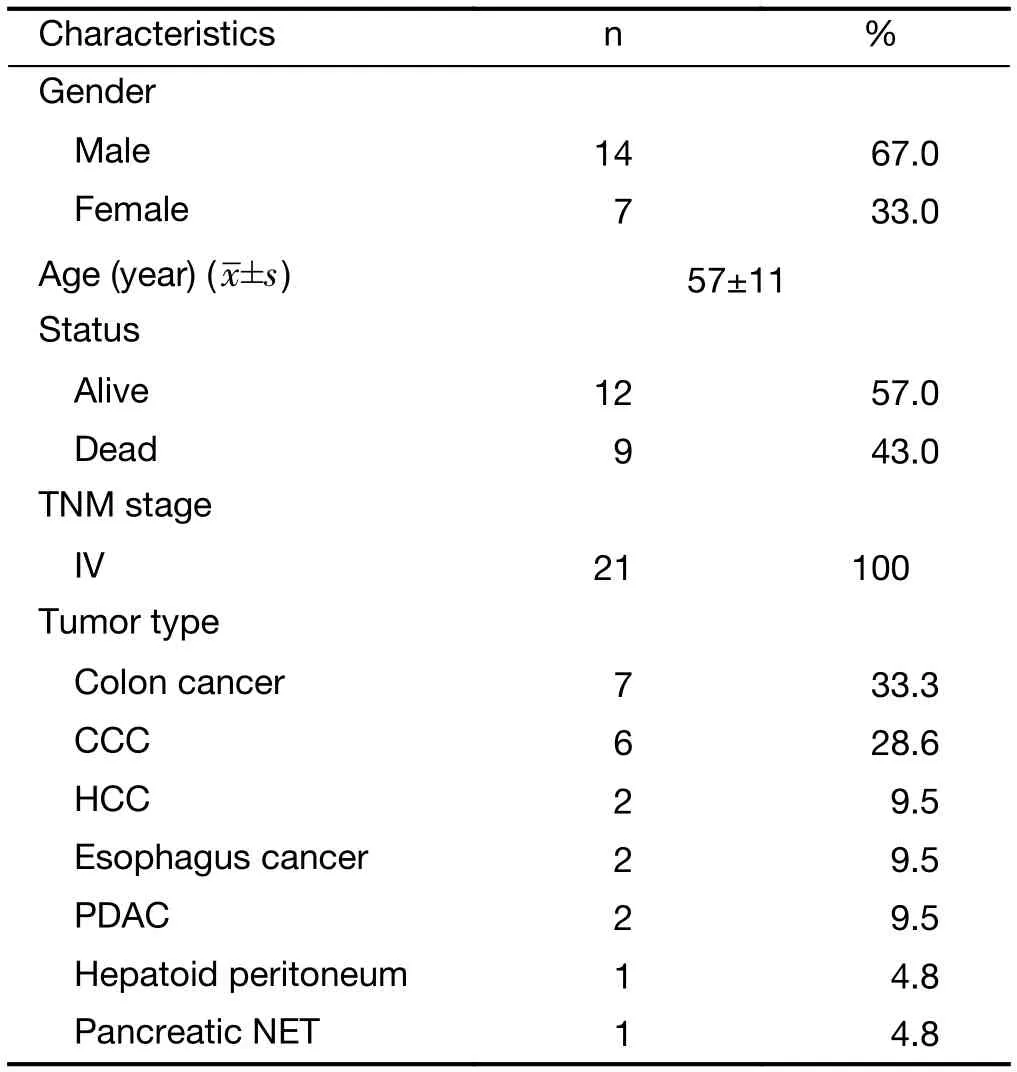

Patients with GI tumors after failure of standard treatment were real-time biopsied. Fresh tumor material was investigated for possible druggable targets via next generation sequencing (NGS), IHC and cytogenetic analysis. Results of the MP were discussed by a MDT within the frame of a tumor board for treatment decision(14). Out of 114 screened patients for the original EXACT trial, 55 (48%) were eligible to start targeted treatment based upon the MP derived from real-time biopsy. From those 55 patients, 21 (38%) were diagnosed with GI malignancies. Fourteen (67.0%) men and 7 (33.0%) women with a mean age of 57 (range, 26-72) years were enrolled.At time of censoring (12/31/2016), 12 (57.0%) patients were alive, while 9 (43.0%) patients were deceased. Most frequent malignancies that were enrolled and treated were colon cancer (n=7, 33.3%) and cholangiocarcinoma (CCC)(n=6, 28.6%) (Table 1).

Table 1 Patient characteristics (N=21)

MP

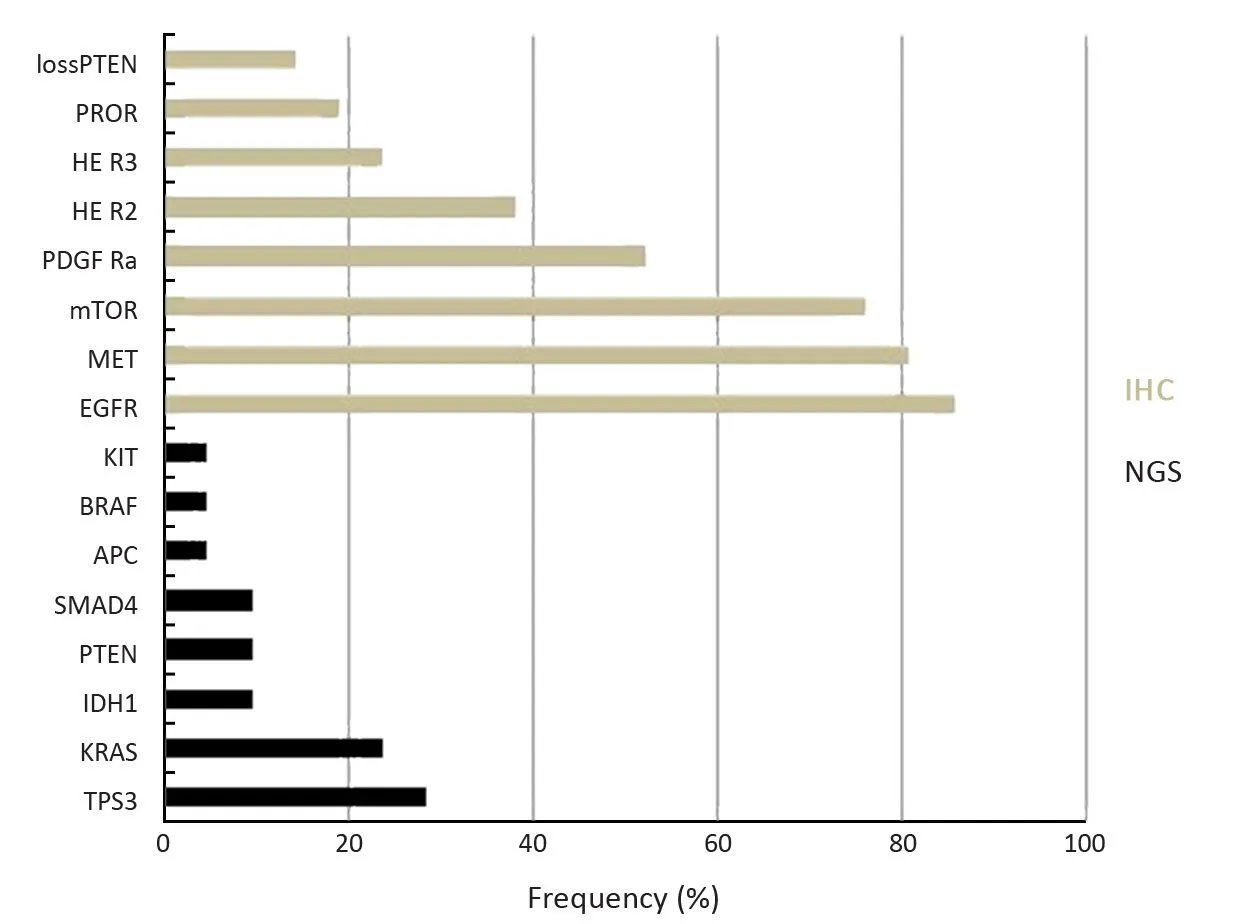

Tumor samples were analyzed via NGS, IHC and cytogenetic analysis using the MONDTI platform (14).Most frequent somatic mutations discovered wereTP53(29%),KRAS(24%),IDH1(10%),PTEN(10%) andSMAD4(10%) (Figure 1). IHC could reveal protein overexpression for EGFR in 86%, MET in 81%, mTOR in 76% and PDGFRa in 52% of patients. The results of cytogenetic analysis (fluorescencein situhybridization, FISH) did not affect the treatment suggestion (data not shown).

Targeted therapy

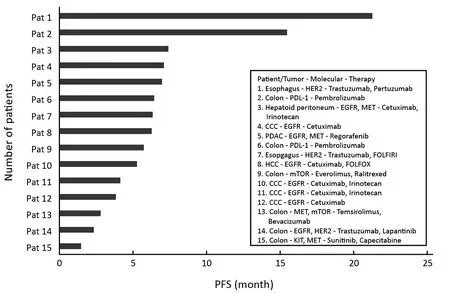

The median PFS1/PFS0 ratio of all patients was 1.59(quartile 0.43/12.76). Out of 21 patients, 15 (71%) showed a PFS1/PFS0 ratio >1.0 in favor of experimental targeted therapy. As shown inFigure 2, targeted treatment was chosen according to the individual tumor profile and consisted of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, checkpoint inhibitors, growth factor receptor antibodies +/— endocrine treatment.

Response rate

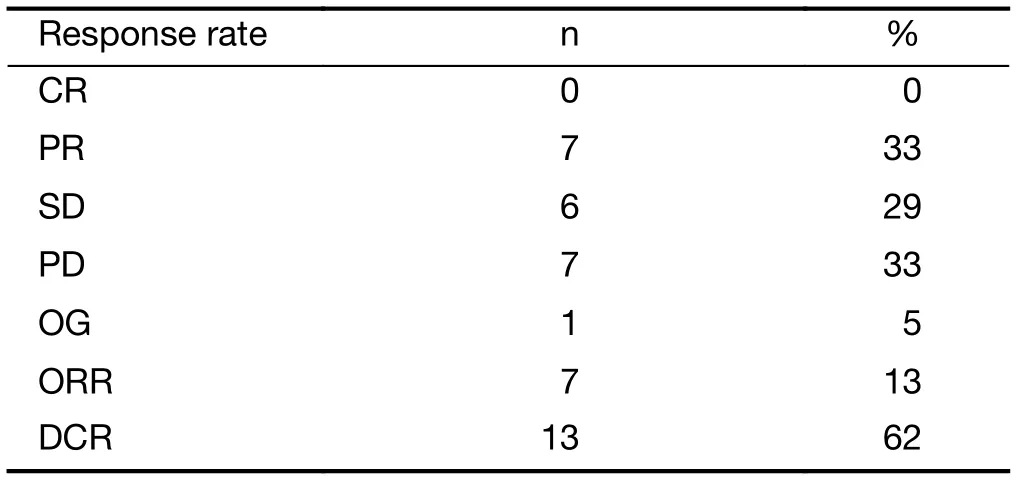

Seven (33%) patients receiving targeted treatment experienced an overall response according to RECIST(Table 2). The disease control rate (DCR) was 62% (n=13).Out of 21 patients suffering from GI tumors, 7 (33%)patients had a partial remission, while 6 (29%) patients had a stable disease according to RECIST 1.1 criteria. Seven(33%) patients did not benefit from therapy and were progressive (one patient was still under experimental therapy and was not evaluated for treatment response at the day of censoring).

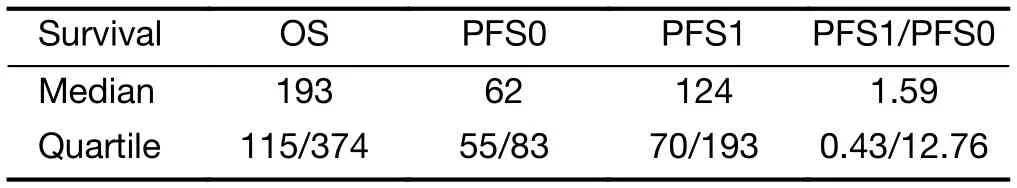

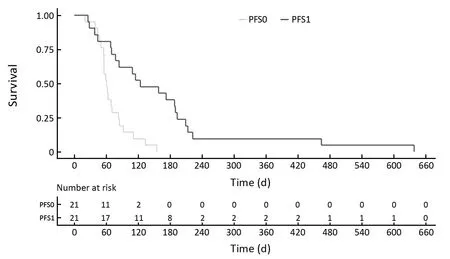

Survival data

The median PFS1 was 124 d (quartiles 70/193 d), whereas median PFS0 was 62 d (quartiles 55/83 d; P=0.014)(Table 3,Figure 3). The bootstrap 95% CI of the median of the PFS1/PFS0 ratio is 4-128. Median OS was 193 d(quartiles 115/374 d). The linear model showed that neither age nor gender had a significant influence on PFS1-PFS0.

Figure 1 Frequency of alterations in molecular profile (MP) as detected by next generation sequencing (NGS) and immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Discussion

Figure 2 Molecular target and treatment of 15 patients with progression-free survival (PFS) ratio (PFS1/PFS0) >1. CCC,cholangiocarcinoma; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Table 2 Treatment response rate upon experimental therapy (N=21)

Table 3 Survival data

In this study we present a subgroup of the prospective clinical phase II EXACT trial to determine the efficacy of a MP-based therapy in pretreated GI cancer patients. Tissues derived from real-time biopsies of patients, refractory to standard therapy treatment, were characterized for their MP. Treatment suggestions were derived from the MP by the MDT. Out of 55 patients, 21 suffered from GI tract cancer. The median PFS of GI cancer patients under experimental treatment was 124 d and was significant OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival. PFS0 was defined as PFS at the last line of standard therapy, whereas PFS1 refers to the experimental therapy.longer than the median PFS upon the standard treatment immediately given before (62 d). Notably, 71% of patients(n=15) achieved a longer PFS in the experimental arm when compared with the immediately preceding treatment resulting in a median PFS ratio of PFS1/PFS0=1.59(quartiles 0.43/12.46). When compared with other patients included in this trial, GI malignancies seem to be sensitive for molecular-based treatment concepts. Furthermore,shrinkage of the tumor upon the experimental treatment was observed in 33% of patients while the DCR was 62%.Tumor shrinkage in this late line setting is not common as the Recourse (15) and Correct (16) trials in metastatic colorectal carcinoma (mCRC) patients revealed. Finally,the median OS was 193 d (quartiles 115/374 d) which is a promising number for an experimental treatment after failure of standard treatment options.

In one of the first individualized treatment studies in cancer, von Hoffet al. reported beneficial effects of molecular profiling of patient’s tumors (17). Their study showed that 27% of the patients had a benefit from an individual targeted approach resulting in a significantly longer PFS when compared with the PFS of the previous regimen of the same patient (PFS ratio ≥1.3; 95% CI,17%-38%; one-sided, one-sample P=0.007). Whether the genomic-guided approach to treatment results into beneficial outcomes for patients with GI cancer is still being studied and only few reports exist. By molecular profiling of 68 patients suffering from CRC with following targeted therapy in a clinical phase I trial, no clinical benefit was found with treatment of matched targeted agents (16). However, only few potential aberrations(KRAS,BRAF,PIK3CAmutations,PTENandpMETexpression) were considered in a retrospective setting from baseline biopsies. This also might not reflect the instable cancer genome especially when treated with targeted agents such as anti EGFR antibodies. The beneficial outcome in our study might be explained by the fact of progress in diagnostic techniques and particularly of the multitude of therapeutic options including immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Figure 3 Progression-free survival (PFS) upon last standard therapy (PFS0) and experimental individualized therapy (PFS1).

Now, multiple promising targets have been applied with mixed results. Recently, vemurafenib failed to show beneficial activity as a single agent inBRAF V600Emutated patients (17). Actually, simultaneous blockade of the Wnt signaling pathway in combination with EGFR and BRAF inhibitors is investigated in an ongoing clinical trial (No.NCT022781333). Furthermore microsatellite instability(MSI)-high enhances immunogenicity due to neoantigenspecific tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. A phase II study already demonstrated clinical response with pembrolizumab by blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction in MSI-high patients (18). Patients with PD-L1 expression were also included in this study and showed a beneficial effect on PFS when compared with the treatment which was last given before. In gastroesophageal cancer, HER2 amplification was found to bear beneficial effects on survival. Patients who were treated with trastuzumab and combination-chemotherapy showed improved OS (median 13.8vs.11.0 months, P=0.0046) when compared to patients treated with chemotherapy alone (19). In addition, the two esophageal patients who showed beneficial effects in this study had a HER2 mutation. In consideration with the mixed results in different basket trials it becomes more and more important to search for those registered targeted anticancer drugs which showed beneficial results in previous studies. In this context, American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) is developing the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry (TAPUR) study which aims to facilitate patient access to marketed drugs which are predicted to be beneficial based on the analysis of patients’ genomic profile of tumors.

In contrast to the previous studies, the EXACT trial was not limited to a certain mutation but considered NGS,cytogenetic analysis as well as IHC profiling. However, this study has some limitations. The original EXACT trial was not designed to investigate GI malignancies but was open to all solid tumors. Furthermore, this prospective clinical trial was not randomized to a control group but considered patients as its own control as it was described previously(17). Finally, the sample size of GI cancer patients was rather small (n=21). However, we demonstrated that MP-based treatment decisions are feasible for extensively pretreated GI cancer patients with certain characteristics to improve their prognosis upon failure of standard treatment options.

Although the number of patients is limited, the promising results of this study in combination with the progress in molecular technologies and increasing numbers of new targeted treatment options urge personalized medicine (PM) in the focus of future treatment concepts in cancer.

Conclusions

In GI malignancies the concept of PM was not investigated so far. In this work we describe PM as a promising approach for GI cancer patients who have no further treatment options after failure of standard therapy. Further prospective clinical trials with a higher number of patients are urged.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Medical University of Vienna.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Chinese Journal of Cancer Research2018年5期

Chinese Journal of Cancer Research2018年5期

- Chinese Journal of Cancer Research的其它文章

- Clinical study of ultrasound and microbubbles for enhancing chemotherapeutic sensitivity of malignant tumors in digestive system

- Probe-based confocal endomicroscopy is accurate fordifferentiating gastric lesions in patients in a Western center

- A comparative study of totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy versus laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients: Short-term operative outcomes at a high-volume center

- Immunohistochemical expression of thymidylate synthase and prognosis in gastric cancer patients submitted to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy

- Oxaliplatin plus S-1 or capecitabine as neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer with D2 lymphadenectomy: 5-year follow-up results of a phase II-III randomized trial

- Anatomical variation of infra-pyloric artery origination: A prospective multicenter observational study (IPA-Origin)