Order of Precedence Between Local Laws of Cities with Subordinate Districts and Regulations of Provincial Governments Clarifying Premises for Discussion Based on the Characteristics of Laws

Zheng Tai’an

Following the revision ofLegislation Law, it is important that academic discussions be conducted based on common grounds to shift the focus from legislation to interpretation. This can help us better understand and applyLegislation Lawand, more importantly, fully explainLegislation Lawthrough practical, applicable analysis and argumentation. Thus, Xi Jinping reported at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China,“Just as there are no bounds to practice, there is no end to theoretical exploration.” Advanced academic and theoretical study are needed to fully explain the legislative rules that have been contentious among scholars with interpretative theory. This paper uses interpretative theory to study the issue of the order of precedence between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and the regulations of provincial governments.

1. Dif fi culties in determining the order of precedence between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and the regulations of provincial governments

Article 95 of the revisedLegislation Lawprovides rules for arbitration in case of clashes between local laws and regulations. As a matter of fact, the same content has been included since 2000 and can be found in Article 86 of the 2000 version ofLegislation Law, Article 94 of the first draft amendment for public comment in 2012, and Article 95 of the second draft amendment for public comment in 2014. Although not a single word is altered, the newLegislation Lawhas introduced a change①The change was introduced mainly in response to the call of the Third Plenary Session of the CPC 18th Central Committee to “gradually increase the number of larger cities with local legislative power” and that of the Fourth Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee to “grant legislative power to cities with subordinate districts.”to the legislative system(Wang, 2006, p.1)by giving legislative power, originally held by larger cities only, to cities with or without subordinate districts as well as autonomous prefectures across the nation (For the sake of this paper, the laws enacted by the local people’s congresses and their standing committees in autonomous prefectures and cities without subordinate districts are not taken into consideration). The scope and number of legislative entities are thus expanded significantly.

Article 89 and 91 of the newLegislation Lawdetails the order of precedence between local laws and regulations, but there seems to be a lack of description regarding the order of precedence or rules for arbitration between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and the regulations of the governments of provinces and autonomous regions. Article 95 deals with the precedence levels of local laws and the regulations of State Council departments but doesn’t clarify the relationships between local laws and the regulations of local governments (although it is provided that the regulations of State Council departments and those of local governments are equally authentic). It may have been assumed that it is only necessary to determine the order of precedence between the laws and regulations of the same level(horizontal) as Article 89 has already clarified the order of precedence between local laws and local departments’ regulations of different levels(vertical). This presents a logical dilemma, as Article 91’s statement that the regulations of State Council departments and those of local governments are equally authentic clashes with Articles 89 and 95. However, that is beyond the focus of this paper. The order of precedence between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and the regulations of provincial governments is the issue that is left unaddressed concerning the relationships between local laws, the regulations of State Council departments and those of local governments in different regions and at different levels. The issue is in fact a continuation of one that has existed since the 2000 version ofLegislation Law. The problem then was “the order of precedence between the local laws of larger cities and the regulations of the governments of provinces and autonomous regions.”Legislation Lawhas not offered an answer.

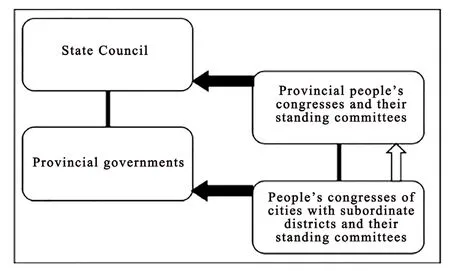

From the perspective of administrative divisions, which is also the angle from which most people would view the issue, cities with subordinate districts are prefecture-level or subprovincial-level administrative units, while provinces and autonomous regions are provinciallevel administrative units; it’s therefore tempting to draw the conclusion that the regulations formulated by the latter should take precedence over the local laws enacted by the former. Nevertheless, the reality is much more complicated. Some hold that the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments (Ruan, 2011, p.93). Their main argument is the “approval theory” (the white arrow in Figure 1). Specifically, it is argued that the local laws of cities with subordinate districts are approved by the standing committees of provincial people’s congresses and that the legislative power of cities with subordinate districts is an extension of that of provinces; therefore, the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and those of provinces and autonomous regions should be equally authentic.①The argument was made by Tian Wanguo, director of the legislative affair commission of the Standing Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Congress,at the Seminar on the Theory and Practice Regarding the Legislative Power of Cities with Subordinate Districts, which was co-hosted by Sichuan Academy of Social Sciences and Sichuan Law Society on the afternoon of July 30, 2015. See also: National Law Office of Legislative Affair Commission of National People’s Congress. (2015). Interpretation of legislation law of the People's Republic of China. China Legal Publishing House. p. 267; Ruan Rongxiang, et al. (2011).On the theory and practice of local legislation. Social Sciences Academic Press. p. 175.On the other hand, logical analogy (the black arrows in Figure 1) and the part ofLegislation Lawconcerning legitimacy review (the black vertical bar on the right side of Figure 1), in addition to the aforementioned administrative hierarchy, are the main arguments some scholars and researchers have used to prove that the regulations of provincial governments should override the local laws of cities with subordinate districts (Gu, 2006). First, since the laws enacted by the State Council take precedence over the local laws by provincial people’s congresses and their standing committees, a parallel conclusion can be drawn (the left of black arrows in Figure 1) – the regulations formulated by provincial governments, which are subordinate to the State Council, should have a higher precedence level than the local laws enacted by the people’s congresses of municipalities with subordinate districts and their standing committees,whose administrative level is lower than that of the people’s congresses of provinces and their standing committees. Second, it is argued that only when the regulations of provincial governments override the local laws of cities with subordinate districts is there a need for the standing committees of provincial people’s congresses to conduct legitimacy reviews when the two clash. Essentially, both arguments draw on the administrative hierarchy. There are two sides to logical analogy, legitimacy review as well as administrative hierarchy. The three can be integrated into one. The two contrasting views both have their supporting arguments. As is generally accepted, nature is so generous that one can come up with supporting arguments for almost any view. As a result, a dilemma is presented to scholars.

Figure 1. Arguments for the order of precedence between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and the regulations of provincial governments

The order of precedence between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and the regulations of provincial governments has an impact on the execution of power and the interests of the parties involved. It is a value judgment issue, which means that there is no absolute right-or-wrong answer as judgment is based on the values applied.Due to varying family and educational backgrounds and knowledge of the world, people may adopt different value systems and consequently arrive at different conclusions, making it difficult for them to reach an agreement on an issue. Therefore, to make the discussion more effective, it is necessary to clarify the premises first so that debate can be made based on agreed rules. This enables scholars to base their discussions on pre-defined premises and consequently better understand the views and arguments of the other side. Additionally, they will find it easier to accept different conclusions when they know different sets of premises or values are applied.①A’s daughter addresses a colleague of his as“elder brother.”The colleague asked why not uncle. A explained that his daughter calls whoever is not yet a father or mother “elder brother”or“elder sister”and whoever is“uncle”or“aunt.” In this case, the daughter has a premise in mind when she determines how to address others, and will arrive at different conclusions depending on whether the premise is met. A’s colleague accepted the address after A’s explanation.A consensus was thus reached. This example suggests that by basing discussion in academic research and practice on clarified premises can help create a minimum level of common understanding.

2. Clarifying premises: Distinguish between traditional and postmodern legislation

Legislative issues associated with all existing laws in human history, whether they are vague,contradictory, or incomplete, are subject to debate because of their value-judgment nature. There may be different voices before, during and after the legislative process. Given the history of China’s written laws, if we look at the positive laws in the country from a chronological viewpoint, it is possible to broadly classify them into traditional laws and postmodern laws. The use of the word“postmodern” may raise some eyebrows, as there is confusion as to whether “postmodern” is used in contrast to “modern” or whether it represents a way of thinking and viewing the world (Ji, 1996;Su, 2004, p.286; Wang, 2006, p.285). However, the fact that there are two different interpretations of“postmodern” doesn’t invalidate the use of the word in this paper.

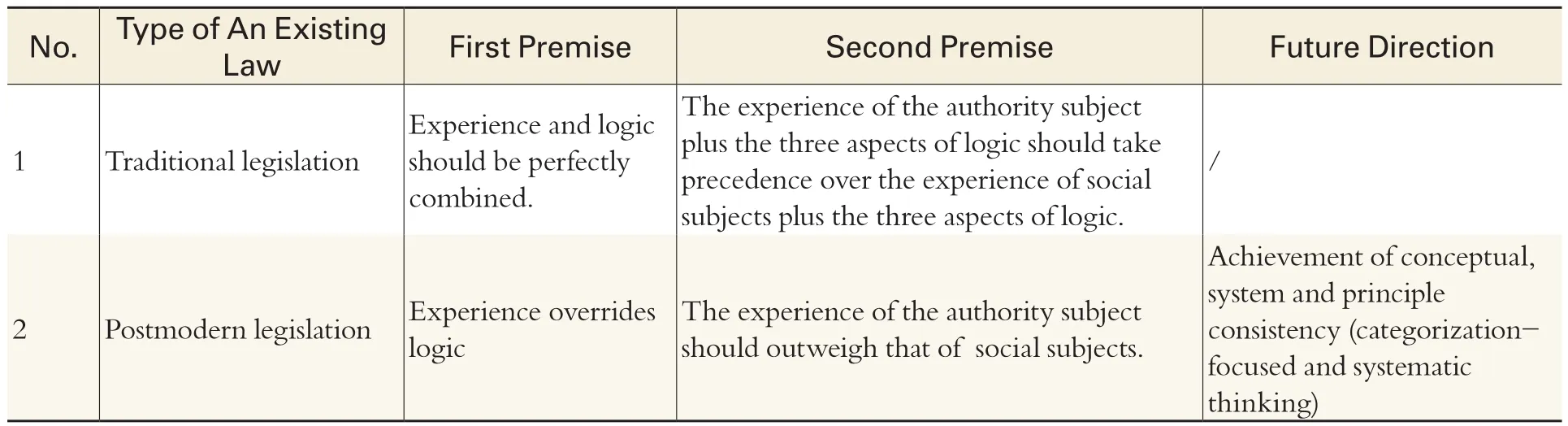

Any classification that is significant is one that is purposeful. In this paper, the purpose of classifying laws into traditional laws and postmodern laws is to clarify the premises for discussions concerning different laws, which help enhance the effectiveness of the discussions. Traditional laws such as civil and criminal laws are a perfect combination of experience and logic. This is mainly because traditional laws are based on thousands of years of experience and the efforts of generations of legal theorists. Traditional laws draw on practical experience and are also logically legitimate in terms of systems, categories and rules. When discussing tort liability legislation, Wang Shengming, a legislator, once said that legislation should be both useful and logical.②On the evening of October 29, 2009, Wang Shengming, the then director of the Office for Civil Law, Legislative Affairs Commission of National People’s Congress and deputy director of the Internal and Judicial Affairs Committee of National People’s Congress, made the remark in a lecture titled “Thoughts on Tort Liability Legislation” given in the International Lecture Hall of Mingde Law Building, Law School of Renmin University of China.The two include experience and logic respectively. This indicates that traditional laws are indeed a combination of experience and logic. Postmodern laws such as environmental and labor law value experience more than logic.This is primarily because postmodern laws did not come into being until modern times. Labor law, for instance, is deemed to have originated as late as 1802, some 200 years ago. It is therefore more practical than logical. The primary goal of postmodern legislation is to offer solutions to practical problems, regardless of their logic. That is why many postmodern laws seem odd compared with traditional laws. Professor Su Li pointed out when talking about postmodern thought and its impact on legal studies and legislation in China, that postmodernism does have its conflicting, incoherent and illogical side (2004, p. 292). In classifying existing laws into traditional and postmodern laws, this paper intends to clarify the premises for discussions concerning different laws by taking into consideration the emphasis they give to experience and logic.

If the discussions concern traditional legislation,as a minimum rule, equal emphasis should be given to experience and logic and focus should be placed on the perfect combination of the two. Among debaters whose arguments are in keeping with practical experience but illogical, logical but run counter to practical experience, and both logical and in keeping with practical experience, the last should prevail.

In contrast, if the discussion involves postmodern legislation, as a minimum rule,experience should be prioritized. Logic, in this case,plays a lesser role. The focus should be on finding the most practical interpretation and implementation of a perhaps incoherent law. Logic may have been frequently associated with science by Hegel (1966),but in the eyes of postmodernists, logic is simply unimportant (P. 23). Therefore, among debaters whose arguments are in keeping with practical experience but perhaps illogical, logical but run counter to practical experience, and both logical and in keeping with practical experience, the first should prevail. Prioritizing experience over logic doesn’t mean that logical elements cannot be injected in amendments in the future to meet the mandatory requirements of the system as studies provide additional information (discussions can even be carried out from the perspective of logic when experience is absent) (Cardozo, 1998, pp.17-18). Postmodern legislation can thus eventually transform into traditional legislation. In this sense,it can be said that experience underpins China’s legislation, while logic lies behind the country’s legislative theory.

The above content deals with the clarification of the first premise based on the characteristics of the law in question. If it is still difficult to determine which side is superior, we should move on to the second premise. To clarify the second premise, we need to further break down the two factors singled out above, namely experience and logic. By the authority and status of the subject,experience can be classified into the experience of the authority (the legislature, administration,judiciary, etc.) and that of society (the general public). The experience of the authority subject may be found in positive laws, documents detailing legislative backgrounds, or memories. It is more authoritative than the experience of the public and exhibits a clear intention to offer solutions. It is relatively easy to understand that positive laws outweigh the experience of social subjects. It is an inevitable product of the rule of written laws. Also understandable is the statement that documents detailing legislative backgrounds take precedence over the experience of social subjects, because the content and spirit of those documents are reflected in positive laws. What one may find hard to accept is the saying that the memories of the authority –as in “We enacted the law in the first place to ... ”“The purpose of the legislation is ... ” “We noticed at the time of legislation that ... ” etc.—also outweigh the experience of social subjects. Such memories are legislative background materials too, though recorded in a different form. Given that social subjects is generally at a disadvantage compared with the authority subject in terms of the level of participation in legislation, access to legislation information, knowledge of the actual legislative process, that “the memories of the authority subject override the experience of social subjects” can at least be taken as a lesser rule. Regarding the logic factor, based on visibility, it can be divided into conceptual consistency, system consistency and principle consistency. A view or a set of arguments that are consistent in all three aspects should be superior to those that are consistent in only one or two.

If the discussion involves traditional legislation,as a minimum rule, the experience of the authority plus the three aspects of logic should take precedence over the experience of social subjects plus the three aspects of logic. On the other hand, if the law in question is a postmodern law, as a minimum rule,the experience of the authority subject should override that of social subjects, regardless of logical consistency. That said, there is room for improvement for postmodern legislation with respect to logic. Postmodern laws have the potential to eventually achieve conceptual, system and principle consistency through theoretical progress.

Clarifying the two premises (see table 1) can help debaters better understand the views and arguments of the other side. They will also find it easier to accept different conclusions when they know different sets of premises or values are applied. It must be pointed out that the views,arguments and conclusions that are deemed superior are not necessarily correct. There is not an answer to a value judgment issue whether it is absolutely right or wrong. It is simply a matter of which one is more acceptable.

3. Applying the right premise by identifying the experience and logic

The debate over the precedence of the laws or regulations has no reason to continue if the law has explicitly stipulated which one shall prevail. The fact, however, is just the opposite. In some cases,there is even no existing benchmark law available for comparison, and the debate over that matter may become antagonistic with different people voicing wildly different opinions. While the debate often ends up without reaching any consensuses,the people involved in the debate might change their positions under the influence of such factors as scenario, relationship and interest. In the spirit of utilitarianism, (Bentham, 2000) I seek to shed some light on the endless debate over “the order of precedence between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and regulations of provincial governments and rules for arbitration” by applying the predefined premises above.

Table 1 Premises for Discussion

Legislation Lawis arguably a typical postmodern law, which bears such distinctive features as “absence of logic and practicality.” For example, the inclusion of ten articles on delegated legislation in the newLegislation Law(totally, a mere 105 articles) is a clear indication of legislators’ keenness to address the practical issues regarding delegated legislation. But,the effort fails owing to the logical contradictions in terms of four aspects, including wording and the expiration time of the delegation(Zheng & Zheng,2015). Another case in point, is that Article 91’s statement about the regulations of administrative departments and those of local governments being equally effective contravenes that of Articles 89 and 95. Accordingly, the issue of “the order of precedence between local laws of cities with subordinate districts and regulations of provincial governments and rules for arbitration” must be looked at against the backdrop of postmodern legislation. The premises for postmodern legislation,rather than those for traditional legislation, shall apply while delving into this issue.

Considering the premises predefined above,the first premise used to weigh the conclusion concerning the issue of “the order of precedence between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and regulations of provincial governments”is that “experience shall override logic.” As such,we must first dig into the grounds people use to derive their conclusions. The argument that “the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments” draws mainly from the “approval theory,” while the reasoning of the opposing views reflects the thinking of “l(fā)ogical analogy” and“l(fā)egitimacy review,” both of which can eventually be boiled down to “administrative hierarchy.”Apparently, no solid conclusion can be drawn in this round, as the conclusions of both sides are derived based on experience.

In this case, we shall resort to the second premise, which is “the experience of the authority subject should take precedence over that of social subjects.” As such, we should continue to identify the subject of the experience. The argument that “the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments” is supported primarily by the practical experience of the legislative body, which can then be translated into the interpretation in the authoritative manuals(Qiao, 2008, p.258) composed and published by the legislative body and that by the officials from the commission of legislative affairs of the standing committees of provincial people’s congresses at related seminars. Whereas, the argument that“the regulations of provincial governments should take precedence over the local laws of cities with subordinate districts” draws mainly on the experience of social subjects, which is essentially nothing different from common sense like “the higher-level administrative depantments override those at the lower-level.” According to the second premise, the later argument, which is based mainly on the experience of social subjects, shall give way to the former argument, i.e. “the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments,”which is derived mainly from the experience of the authority subject. Even so, this can’t be deemed,in any way, as the justification for the argument of“the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments” being absolutely right. It only proves that the former argument, compared with the argument of “the regulations of provincial governments should take precedence over the local laws of cities with subordinate districts,” is bettergrounded.

Legislation Lawis a typical postmodern law wherein the absence of logic can be observed.Although we have given more weight to the argument of “the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments” based on the earlier discussion, the view is still logically challenged in terms of the three dilemmas mentioned above. More studies on that matter must be carried out in the future.

The first logical dilemma is mirrored in the ambiguity in the definition of terms. The terms“l(fā)ocal laws” and “the same level” stated in the first provision of Article 89 inLegislation Law, for example, are ill-defined. And the provision can have two completely different interpretations by applying different premises. Let’s first assume that the “l(fā)ocal laws” refers specifically to the “l(fā)ocal laws” of “cities with subordinate districts,” we can then conclude that the local laws enacted by the people’s congresses of cities with subordinate districts and their standing committees enjoy precedence over the regulations issued by the governments at the same level. Even so, the argument that “the local laws enacted by the people’s congresses of cities with subordinate districts and their standing committees should enjoy precedence over the regulations issued by the provincial governments” still seems too farfetched, as it clearly states in the provision that the local laws enacted by the people’s congresses of cities with subordinate districts and their standing committees should “enjoy precedence over the regulations issued by the governments at the same or lower levels,” not “by governments at higher levels.” As above, the argument that“the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments” does not hold water when measured against the first provision of Article 89 inLegislation Law. Additionally, we can stop puzzling over the administrative depart ment the provision refers to, be it the city with subordinate districts or a provincial people’s congress and its standing committee. We can thus assume that the “l(fā)ocal laws” stated in the provision cover those enacted by the people’s congresses of cities with subordinate districts and their standing committees. Then, we can arrive at the rough conclusion that “the local laws (the local laws enacted by cities with subordinate districts included) should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments.” But,the conclusion again runs contrary to Article 91 and Article 95 inLegislation Law, which deem the regulations of provincial governments and those of the State Council departments equally effective.To say that the local laws enacted by the people’s congresses of cities with subordinate districts and their standing committees should enjoy precedence over the regulations of provincial governments is to say that the local laws enacted by the people’s congresses of cities with subordinate districts and their standing committees should take precedence over the regulations of State Council departments.If that’s the case, the ruling concerning the contradictions of the local laws and regulations of State Council departments in Article 95 would make no sense. The contradiction is traced back to the fundamental question of whether the “the same level” should be interpreted as “cities with subordinate districts” or “l(fā)ocal laws.” The term“the same level” should be clearly defined in order to afford logical consistency forLegislation Law. Otherwise, the logical dilemma will persist,no matter if it is interpreted as “cities with subordinate districts” or “l(fā)ocal laws.”

The second logical dilemma concerns legislation system consistency and is found in the following two aspects. According to Article 72 and Article 82 inLegislation Law, the local laws of cities with subordinate districts shall be approved before they can be enacted (approval authority: the standing committees of provincial people’s congresses). By contrast, the regulations formulated by the people’s governments of cities with subordinate districts can be enacted at their own discretion. This runs counter to the principle of “similar cases to be handled in similar ways” advocated in the academic world.To the public, the people’s congresses and their standing committees are unquestionably the entitled legislative bodies. With other things being equal, it appears, however, that the entitled legislative bodies are more restricted than other legislative bodies or bodies with no legislative power. This puts the legislative bodies, whose major responsibility is exercising legislative power, in an awkward position.In addition, if, as the “approval theory” suggests,the local laws of cities with subordinate districts are pulled to an equal level with regulations of provincial governments simply because they are approved by the standing committees of provincial people’s congresses, then, according to Article 75 inLegislation Law, the autonomous regulation or separate regulation enacted by an autonomous region should be deemed as national law as it is reviewed and approved by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Furthermore,the autonomous regulation or separate regulation enacted by an autonomous prefecture or autonomous county will be on a par with regulations of provincial governments as it is reviewed and approved by the standing committees of the provincial people’s congresses (Wang, 2006). Most people will certainly find this conclusion unacceptable (Zheng, 2014).

The third logical dilemma concerns the conflict of value judgment. The argument “the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments” draws mainly from the fact that the local laws of cities with subordinate districts are reviewed and approved by the standing committees of provincial and autonomous people’s congresses.As such, the legislative power of the cities with subordinate districts should be deemed an extension and integral part of the provincial legislative power.As the provincial laws and laws of autonomous regions enjoy higher ranking in authority over the regulations of provincial governments, so should the local laws of cities with subordinate districts. But,that would render pointless the stipulation that the local laws of cities with subordinate districts shall not contradict the provincial laws inLegislation Law.The conclusion of “the legislative power of cities with subordinate districts being an extension and integral part of the provincial legislative power”is derived on the basis of approving the expansion of legislative power, while the stipulation that “the local laws of cities with subordinate districts shall not contradict the provincial laws” adheres to the principle of restricting legislative power. This presents a conflict of principle judgment. If we factor in the time element however, the conflict could see a bit of mitigation. When the stipulation is interpreted from another standpoint, it makes sense that the local laws of cities with subordinate districts shall not contradict the laws at provincial levels, since they are not put on a par with the provincial laws until they are approved by legislative units at provincial levels.But, this interpretation doesn’t stand to reason. Some people may argue that there is not supposed to be any issue of contradiction in the first place, as the local laws of cities with subordinate districts are to be put on a par with the provincial laws anyway.

The argument that “the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments” prevails following the previous discussion, but the view is still logically challenged in terms of the three aspects discussed above. We haven’t given much weight to the logical issues in this paper, but this does not mean that theLegislation Lawshould not be logically polished in the future.Legislation Lawis sure to become more logically grounded as the research studies on it advance. Eventually, the postmodern will evolve into the premodern (traditional).

4. Supplementary thinking on prede fi ned premises

Interpretation is necessary to better implement the newly revisedLegislation Law. That is indeed the central focus of interpretive theory. But the interpretation could easily veer off course without any pre-defined premises and rules. That is what makes the pre-defined premises above crucial.

Nevertheless, questions may also be raised about the pre-defined premises. The first one would probably be why the above premises, instead of other premises, should qualify as the premises of the discussion. The topic to be discussed here in this paper involves an existing law, so it makes perfect sense that the premises should be set by considering the nature of that law while the premises are introduced under the guidance of both systematic(which promotes “similar cases to be handled in similar ways”) and categorization-focused thinking(which promotes “an individual case to be handled in an individual way”). These premises are the minimum set of rules derived by weighing the “l(fā)aw in question” against the above two ways of thinking.

The second one would probably be about the premises themselves. According to the second premise, the experience of the authority subject (plus the three aspects of logic) should take precedence over the experience of social subjects (plus the three aspects of logic). This might suggest that the experience of authority subject should always enjoy higher ranking in authority, without any exception. But we cannot rule out the possibility of the authorities sometimes making groundless interpretations. In this case, we must be aware that the logic of the authority subject is not necessarily superior to that of social subjects in traditional legislation. Therefore, the theoretical study on logic still has a major role to play in terms of refining postmodern legislation. Meanwhile, the public must also intentionally collect the materials on legislative background (Zheng & Zheng, 2016) to avoid being misled by the authorities’ groundless interpretations.Furthermore, the authority might not always be more experienced than the public. If the public has more practical advice to offer, the authority will most likely make sure that it is reflected in corresponding laws, thereby combining the experience of the authority subject and the experience of social subjects.

The third one would probably be about the validity of the conclusion derived based on the predefined premises (particularly their effectiveness).We’ve arrived at the conclusion that “the local laws of cities with subordinate districts should take precedence over the regulations of provincial governments” by applying the pre-defined premises.This is equal to implying that the regulations of provincial governments serve no purposes.But enforcing a law is not all about “the law’s relative hierarchy,” there are also cases where“applicability”①should prevail and where the laws that enjoy higher ranking in authority will fail to apply. Therefore, the regulations of provincial governments will not lose their effectiveness.Additionally, the standing committees of provincial people’s congresses are in a position to mitigate and prevent these kinds of contradictions based on the third provision of Article 72 inLegislation Law,Legislation Lawis revised to specify the“order of precedence between local laws of cities with subordinate districts and regulations of provincial governments and the rules for arbitration.” For example, a plan for resolving contradictions can be formulated by the standing committees of provincial people’s congresses as soon as they observe any contradictions between the laws submitted for approval and the regulations of the provincial governments.In this case, the contradictions can be removed during the legislative process. There would be no argument about the order of precedence if the contradictions are addressed before the local laws of cities with subordinate districts become effective. And the significance of the regulations of the provincial governments is also highlighted by doing so.

The more acceptable answer to the “order of precedence between the local laws of cities with subordinate districts and the regulations of provincial governments” is that the former should have more authority than the latter, but more needs to be done to tackle the three logical challenges the conclusion faces.

(Translator: Lin Min, Zhang Congrong;Editor: Jia Fengrong)

This paper has been translated and reprinted with the permission ofLegal Forum, No.1, 2018.

REFERENCES

Gu Jianya. (2006). New exploration of legislative order of precedence.Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences), (6).

[United Kingdom]Jeremy Bentham. (2000).An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. In Shi Yinhong (Trans). The Commercial Press.

Ji Weidong. (1996). Law and society in 21st century – Thoughts after the 31st conference of the research committee on sociology of law of the international sociological association.Social Sciences in China, (3).

National Law Of fi ce of Legislative Affair Commission of National People’s Congress. (2015).Interpretation of legislation law of the People's Republic of China. Beijing: China Legal Publishing House.

Ruan Rongxiang. (2011).On the theory and practice of local legislation. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Su Li. (2004).Rule of law and its local resources. Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press.

Wang Peiying. (2000). Research on the legal status of autonomous regulation and separate regulation.Ethno-National Studies, (6).

Wang Zhendong. (2006).Modern schools of legal thought in the west. Beijing: China Renmin University of Press.

Wang Zhihe. (2006).Study of ideology in postmodern philosophy (enlarged edition). Beijing: Peking University Press.

Zheng Tai’an & Zheng Wenrui. (2015). Systematic thinking on delegated legislation: Contradiction and Solution.Theory and Reform, (5).Zheng Tai’an & Zheng Wenrui. (2016). Duality perspective of data of legislative background.Legal Forum, (6).

Zheng Yi. (2014). Research on the legal status of autonomous decree and special decree: From the perspective of pre-established hierarchy and effectiveness hierarchy.Guangxi Ethnic Study, (1).

Contemporary Social Sciences2018年2期

Contemporary Social Sciences2018年2期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- Chinese Costumes and the Spirit of Chinese Aesthetics

- Building a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind:International Law-based Principles and Approaches

- The Content and Approaches of Human Resource Development in Impoverished Rural Regions in the Context of Targeted Poverty Alleviation

- Coping with Climate Change:China’s Efforts and Their Sociological Significance

- Five Dialectics of Xi Jinping’s Theory on Ecological Progress

- Sharing Economy: A New Economic Revolution to Step into an Era of Ecological Civilization