E-ANA-TUM AND THE RULER OF ARAWA1

Gábor Zólyomi

ELTE E?tv?s Loránd University, Budapest

1I thank Szilvia Jáka-S?vegjártó, Zsombor F?ldi, Ingo Schrakamp, and ádám Vér for reading and commenting on a draft of this paper. All remaining mistakes are my responsibility alone.

1. Introduction

In the inscriptions of E-ana-tum, ruler of Laga?, listing his victories over various cities, there is a four-line long passage that describes E-ana-tum's defeat over the city called Arawa:2On the identification of the city written as URU×Aki with Arawa, see Steinkeller 1982, 244-246 and Molina 2015. In the Old Babylonian literary text I?bi-Erra B (ETCSL 2.5.1.2, Segment C 5) the city is called as the “bolt of Elam” (sa?-kul elam[ki-ma]). Steinkeller 1982, 246 suggests that Arawa “l(fā)ay in northwestern uzistan, in a strategic point controlling the passage from Southern Babylonia onto the Susiana plain. Such a location would fit the designation ‘the lock of Elam' perfectly.” Michalowski et al. 2010, 107-109 suggest an identification of the city with Tepe Musiyān on the Deh Lurān Plain.

(1)

?u-nir URU×Aki-ka, ensi2-be23The 3rd ps. sg. non-human possessive enclitic =/be/ is assumed to be =/bi/ in the earlier literature.This article follows Jagersma (2010, 214-217), who, based on its writings, argues convincingly that the last vowel of this enclitic is in fact /e/., sa?-ba mu-DU, aga3-kar2!(?E3)4For the history of the reading kar2, see Veldhuis 2010, 382.be2-seg10

The translations of this grammatically difficult passage vary greatly; there seems to be no agreement either about its exact meaning or about its grammatical analysis. This paper first evaluates the translations and analyses proposed so far,then, in its second part, a new translation is offered. This translation is based on an analysis of the passage that takes into consideration not only verbal and nominal morphology and syntax, but also the information structure of the passage and the arrangement of the cuneiform signs.

2. Texts and translations

The passage occurs in four inscriptions of E-ana-tum:

- E-ana-tum 1 rev. 7:5'-rev. 8:1 (RIME1.9.3.1 = P222399)5The royal inscriptions are quoted with reference to their number in RIME 1 (= Frayne 2007);their number in ABW (= Steible 1982) is mentioned only to facilitate their identification in certain contexts. P-numbers and Q-numbers refer to the catalogue-numbers of manuscripts and composite texts of the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative Project (https://www.cdli.ucla.edu). Literary texts are quoted with reference to their designation and catalogue-number at the website of the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk). An electronic edition of all royal inscriptions mentioned in this paper can be found at the website of the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Royal Inscriptions project (http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/etcsri).

- E-ana-tum 5 3:17-20 (RIME1.9.3.5, ex. 1 [= ABW Ean. 2] = P222400)6The other ms. of Ean. 5 (4 H-T 007 = P222401) preserved only the beginning of the passage in 3:3 ?u-nir [URU×A]

- E-ana-tum 6 3:16-19 (RIME1.9.3.6, ex. 1 [= ABW Ean 3-4] = P222402)7Note that in Frayne 2007, 151, l. 18: sa? mu-gub-?ba? must be corrected to sa?-ba mu-gub

- E-ana-tum 8 3:10-4:3 (RIME1.9.3.8, ex. 1 [= ABW Ean. 11] = P222411)8The other mss. of the inscription (P222412-P222421, P208504), when they preserve the passage,do not differ from this ms.

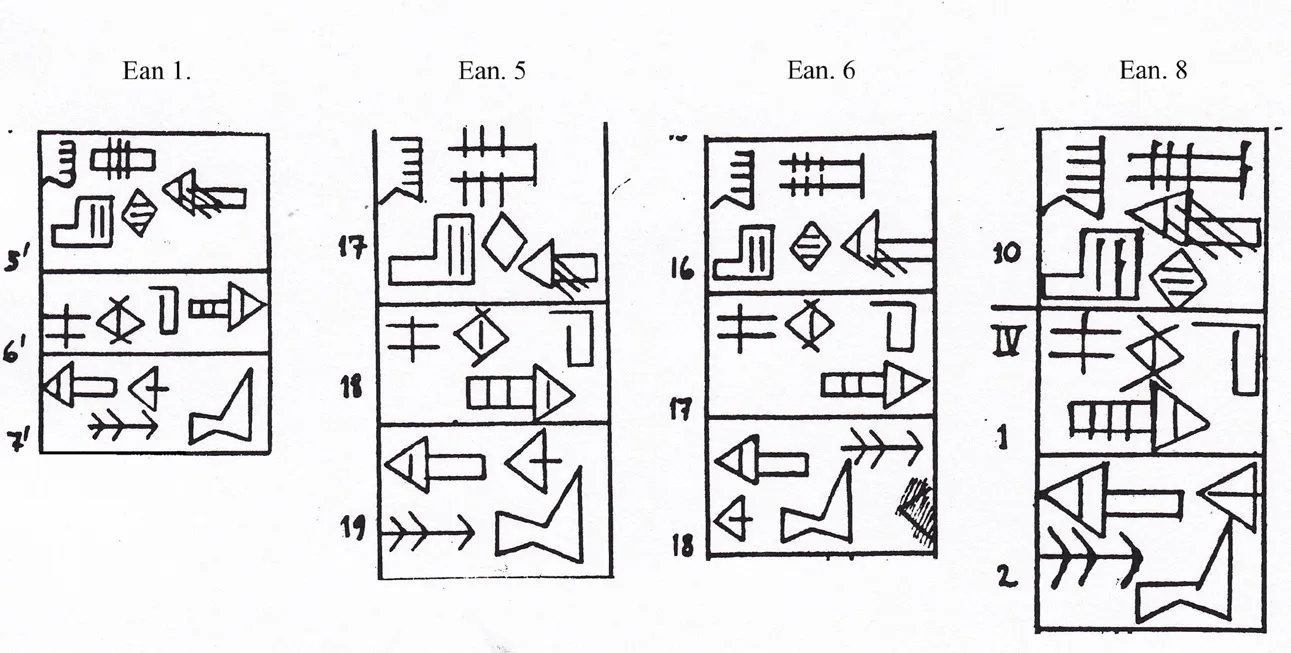

The first three lines of the passage in the four texts are shown below in Sollberger's copy:9From Sollberger 1956.

Fig. 1: The first three lines of the passage

There seems to be no consensus on the interpretation of this passage, as indicated by its divergent translations, some of which are based on a different understanding, and hence transliteration, of the third line of the passage. The translations and paraphrases of this difficult passage can be divided into three groups depending on the assumed “object” of the defeat: i) in which the emblem;ii) in which the city, Arawa; and iii) in which the ruler is considered to be defeated.

i) “emblem”

C. Wilcke: “Das Emblem von URUxA - der Ensi dieser (Stadt) ging an der Spitze- hat er mit [Waffen geschlagen].”10Quoted by Steible 1982, vol. 2, 65.

W. H. Ph. R?mer: “Das Emblem von Urua - dessen Stadtfürst ging ihm voran, er besiegte es… .”11Translation of Ean. 6 in Kaiser et al. 1984, 294.

G. J. Selz: “Das F?hnlein des Stadtfürsten von Arawa, der (pers?nlich) an dessen Spitzen stand, hat er mit Waffen geschlagen.”12Selz 1991, 34; translation of Ean. 8 3:10-4:3, transliterated as “?u-nir uruaki-ka ensí-bi sag mugub-ba GIN2.?E3 bi(2)-sè.”

D. Foxvog: “The Standard of Uru, though by its ruler it had been set up at the head (of it), he defeated it.”13Online translation of Ean. 1 = Q001056, ll. 595'-598'; Ean. 5 = Q001057, ll. 39-42; Ean. 6 =Q001058, ll. 42-44; Ean 8 = Q001062, ll. 29-32 on CDLI (10.11.2017). Foxvog's translation is meant to be a line-by-line translation, which explains its strange word-order.

ii) “Arawa”

F. Thureau-Dangin: “Das Emblem von Uru+A, der Patesi von dieser (Stadt), vor(der Stadt) p fl anzte er es auf. (E-an-na-tum) unterwarf … (diese Stadt)... .”14Thureau-Dangin 1907, 21, 23, 27; translation of Ean. 5 3:17-20, 6 3:16-19, 8 3:10-4:3 (italics is Thureau-Dangin's); transliterated as “?u-nir uru+aki-ka pa-te-si-bi sag-ba mu-gub gìn-?ú bi-sí(g)”(1907, 20, 22 and 27).

G. A. Barton: “The standard of Urua its patesi on its summit planted; in its entirety he (Eannatum) overthrew (it)., … .”15Barton 1928, 35, 37, and 41; translation of Ean. 5 3:17-20, 6 3:16-19, 8 3:10-4:3 (italics is Barton's); transliterated as “?U-NIR URU+Aki-KA PA-TE-SI-BI SAG-BA MU-GUB TUN-BI-?ù SUM” (ibid., 34, 36 and 40).

Th. Jacobsen: “Eannatum tells us … that the ensi of the city of URU×A placed the symbol (?u-nir) of the city at its head and that Eannatum routed it.”16Jacobsen 1967, 101, paraphrase of Ean. 5 3:17-20.

J. Bauer (a): “Von URU×A wurde berichtet, da? er es schlug, obwohl der Stadtfürst das Emblem der Stadt (?u-nir) an deren Spitze gestellt hatte.”17Bauer 1998, 457.

D. Potts: “Arawa, whose ensí had raised its standard, was smitten with weapons.”18Potts 2016, 83; bold is Pott's.

iii) “ruler”

S. N. Kramer: “He conquered the ensi of Urua, who had planted the standard of the city (Urua) at their head (that is, at the head of the people of Urua).”19Kramer 1963, 309; translation of Ean. 5 3:17-20; italics is Kramer's.

E. Sollberger: “Le prince d'Urua marcha devant son emblem: Il le vanquit… .”20Sollberger and Kupper 1971, 58; translation of Ean. 5 3:17-20.

B. Kienast: “jenen Stadtfürsten, der an der Spitze des Feldzeichens von URU×A stand, hat er besiegt… .”21Kienast 1980, 257; translation of the passage in Ean. 5 3:17-20, 6 3:16-19, 8 3:10-4:3;transliterated as “?u-nir-URUxAki énsi-bi sag-ba mu-gub-ba (var. om.) tùn-?è bi-sè.” Note the omitted KA sign after URUxAki.

H. Steible (a): “Den Stadtfürsten des Emblems von URU×A, der (es) an die Spitze (des Aufgebots) gestellt hatte, hat er mit Waffen geschlagen… .”22Steible 1982, vol. 1, 143-144; 147; 154; 163-164, translation of the passage in ABW Ean.1 (= RIME 1.9.3.1), ABW Ean. 2 (= RIME 1.9.3.5), ABW Ean. 3-4 (= RIME 1.9.3.6), ABW Ean. 11 (= RIME 1.9.3.8).

H. Steible (b): “Den Stadtfürsten, der das Emblem von URU×A (an) die Spitze(des Aufgebots) (dort) gestellt hatte, … .”23Steible 1982 vol. 2, 65, in the commentary for ABW Ean. 2 (= RIME 1.9.3.5).

J. Cooper: “He defeated the ruler of Urua, who stood with the (city's) emblem in the vanguard?, … .”24Cooper 1986, 37, 41, 43 and 44; translation of Ean. 1 rev. 7:5'-rev. 8:1, 5 3:17-20, 6 3:16-19, 8 3:10-4:3.

J. Bauer (b) (a “free” translation): “Obwohl der Ensi der Stadt URU×A eine Generalmobilmachung veranstaltete, schlug Eanatum ihn trotzdem.”25Bauer 1998, 457.

G. Magid: E-ana-tum “[defeated] the ruler of Uru'a, who stood with the (city-)emblem at the head (of his army).”26Translation of Ean. 1 rev. 7:5'-rev. 8:1 in Chavalas 2006, 13.

D. Frayne: “He defeated the ruler of Arawa, who stood with the (city's) emblem in the vanguard... .”27Frayne 2007, 139, 147, 151, and 155; translation of Ean. 1 rev. 7:5'-rev. 8:1, 5 3:17-20, 6 3:16-19,8 3:10-4:3.

There exist some translations that cannot be assigned to any of the groups above, as they render only the first three lines of the passage. ?. W. Sj?berg translates the lines as “das Emblem der Stadt U. stellte deren ensi an ihre Spitze.”28Sj?berg 1967, 206, n. 9; translation of Ean. 1 rev. 7:5'-7'; transliterated as “?u-nir-URUxAki-ka énsi-bé sag-ba mu-gub.”B. Pongratz-Leisten copies Sj?berg's transliteration and translation.29Pongratz-Leisten 1992, 302.K. Szarzyńska states: “[t]he text informs us that the ensi of the city of Urua put the standard, ?u-nir, at the border (literally ‘beside the head') of his city waiting for the troops of Eannatum.”30Szarzyńska 1996, 10, paraphrase of Ean. 8 3:10-4:2; transliterated as “?u-nir Uru-aki-ka énsi-bé sag-ba mu-gub” in n. 19.P. Michalowskirepeats this paraphrase with minor modifications: “the énsi of URU×A put the ?u-nir [the standard] beside the vanguard of his city, waiting for the troops of Eannatum.”31Michalowski et al. 2010, 107, paraphrase of Ean. 8 3:10-4:2.

Only Steible's and Wilcke's analyses are known from Steible's commentary on the passage; in the case of all other translations one can only guess the analysis that led to the translation. In the next part of the paper, I will discuss only translations or paraphrases prepared in or after the second part of the 20th century.

3. Steible's analysis and translation

Steible reads the third line as sa? mu-gub-ba in Ean. 1 (= ABW Ean. 1), 5 (= ABW Ean. 2), and 8 (= ABW Ean. 11); while he reads it as sa?-ba mu-gub-?ba? in Ean.6 (= ABW Ean. 3-4). Here follows Steible's interpretation of the passage, which underlies the translation of Steible (a), quoted above:

“In Ean. 3,3:18 ist -bi in sag-ba <*sag-bi-a (Lokativ) auf ?u-nir-URU×Akioder, wegen des Kontextes, auf URU×Akizu beziehen. -bi in ensí-bi nimmt den vorausgestellten Genitiv in ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka (<*…-ak-ak) auf. Da die Wiederaufnahme bereits durch -bi in ensí-bi erfolgt, ist sag(-ba) mu-gub-ba der Genitivverbindung insgesamt attributiv zugeordnet und nicht nur ensí allein, da man sonst ensí / sag(-ba) mu-gub-ba-bi erwarten würde.”32Steible 1982, vol. 2, 64.

For the interpretation of the passage, Steible refers to Gudea's Cylinder A 14:26-27 (cf. the similar passages in Cyl. A 14:16-18 and 14:21-23):

(2) Gudea Cyl. A 14:26-27 (ETCSL 2.1.7)33This passage will be discussed again as ex. (26) below, where a new translation will be suggested.

im-ru-adinana-ka zig3-ga mu-na-?al2, a?-me ?u-nirdinana-kam sa?-bi-a mu-gub

“There was a levy for him on the clans of Inana …, and he placed the rosette, the standard of Inana, in front of them.”

“Im Imru'a der Inanna veranstaltete er ihm (= Ningirsu) ein Aufgebot. Die‘Scheibe' (= A?.ME) - es ist das Emblem der Inanna - stellte er davor.”34Steible 1982, vol. 2, 64-65.

Having taken into consideration this passage, Steible offers a translation different from the one used in his text editions. Unfortunately, he does not explain how this new interpretation follows from his previous grammatical analysis.

“Danach verstehen wir ?u-nir-URU×Aki-ka ensí-bi sag mu-gub-ba als ‘Den Stadtfürsten, der das Emblem von URU×A (an) die Spitze (des Aufgebots) (dort)gestellt hatte, (…)'.”35Ibid., 65.In his first interpretation (= Steible [a]), Steible apparently divides the expression into an anticipatory (= left-dislocated) genitive construction followed by a headless relative clause in apposition, the case governed by the idiom aga3-kar2— sig10is then marked only on the second member of the apposition, a very common phenomenon in Sumerian:

(3)

?unir arawa=ak=ak ensik=be

emblem GN=GEN=GEN ruler=3.SG.NH.POSS36For the abbreviations in the glosses, see footnote 39 below.

head=3.SG.NH.POSS=L1 VEN-3.SG.H.A-stand-3.SG.P-SUB=L2.NH

Approx.: “(He defeated) the ruler of the standard of Arawa, him who placed it in front (of the levied ones).”

Nevertheless, there are three problems with Steible's analysis and the resulting translation. The first relates to the verbal form of the idiom aga3-kar2— sig10; the second one relates to the meaning of the construction with the first three words;and the third one relates to the function of the BA sign in the third line of the passage.

The first problem in fact concerns all translations that take the ruler as the defeated participant, as the prefix-chain of the finite verb rules this interpretation out. The idiom aga3-kar2— sig10case-marks the “defeated” participant with the locative2 case.37For the locative1-3 cases in Sumerian, see Zólyomi 2010; 2017, 201-222 (lesson 14).Consequently, when the defeated participant is human, then it is cross-referenced with a composite 3rd ps. sg. human locative2 prefix in the verbal prefix-chain,38A composite adverbial prefix is composed of i) an initial pronominal prefix, and ii) an adverbial prefix. For the notion of composite adverbial prefixes, see Zólyomi 2010, 580-583; 2017, 79-82(section 6.3), and Jagersma 2010, 381-392 (whose terminology, however, differs from the one applied in this paper).see exx. (4)-(6) below (in ex. [4] the verbal form is written as mu-sig10, which I consider an early defective writing for a later mu-ni-sig10).

When the defeated participant is non-human, then it is case-marked with the non-human locative2 case and is cross-referenced with a composite 3rd ps. sg.non-human locative2 prefix in the verbal prefix-chain, see exx. (7) and (8) below.

(4) Ur-Nan?e 6b rev. 2:1-2 and 3:11-12 (RIME 1.9.1.6b) (P222390)39In the Sumerian examples, the first line represents the utterance in standard graphemic transliteration; the second, a segmentation into morphemes; the third, a morpheme-by-morpheme glossing. Abbreviations used in the glosses: 2 = second person, 3 = third person, A = agent (subject of a transitive verb), ABS = absolutive case-marker, COM = comitative case-marker or prefix, DAT= dative case-marker or prefix, FIN = finite-marker prefix, GEN = genitive case-marker, GN =geographical name, H = human, L1 = locative1 case-marker or prefix, L2 = locative2 case-marker or prefix, NH = non-human, P = patient (object of a transitive verb), POSS = possessive enclitic, S= subject (of a transitive verb), SG = singular, SUB = subordinator suffix, SYN = syncopated verbal prefix, VEN = ventive prefix.

lu2urim5/ummaki, aga3-kar2

lu urim/umma=ak=ra agakar=?

person GN=GEN=L2.H defeat=ABS

mu-sig10S4mu-S6nn-S10i-S11n-S12sig-S14?40The morphological segmentation and glossing of the Sumerian examples are based on the assumption that the Sumerian finite verbal form exhibits a template morphology, and the affixes and the verbal stem can be arranged into fifteen structural positions or slots. In the morphemic segmentation of the finite verbal forms, subscript “S + number” refers to the verbal slots as discussed,for instance, in Zólyomi 2017, 77-90.

VEN-3.SG.H-L2-3.SG.H.A-put-3.SG.P

“He defeated the leader of Ur/Umma.”

(5) En-metena 1 3:14 (RIME 1.9.5.1) (Q001103)

aga3-kar2i3-ni-sig10

agakar=?S2i-S6nn-S10i-S11n-S12sig-S14?

defeat=ABS FIN-3.SG.H-L2-3.SG.H.A-put-3.SG.P

“(En-metena, the beloved child of En-ana-tum,) defeated him (= Ur-Luma, ruler of Umma).”

(6) Sargon 1 16-20 (RIME 2.1.1.1) (Q000834)

lu2unugki-?ga-da?,?e?tukul,

lu unug=ak=da tukul=?

person GN=GEN=COM weapon=ABS

?e?-da-sag3,

S2i-S6n-S8da-S11n-S12sag-S14?

FIN-3.SG.H-COM-3.SG.H.A-strike-3.SG.P

aga3-kar2e-?ne2?-[seg10]

agakar=?S2i-S6nn-S10i-S11n-S12sig-S14?

defeat=ABS FIN-3.SG.H-L2-3.SG.H.A-put-3.SG.P

“He fought with the leader of Uruk and defeated him.”

(7) E-ana-tum 1 rev. 7:3'-4' (RIME 1.9.3.1) (P222399)

su-sin2[ki]-na, aga3-kar2!(?E3)

susin='a agakar=?

GN=L2.NH defeat=ABS

be2-seg10S5b-S10i-S11n-S12sig-S14?

3.SG.NH-L2-3.SG.H.A-put-3.SG.P

“He defeated Susa.”

(8) E-ana-tum 11 side 1, 3:4'-5' (RIME 1.9.3.11) (P222462)

?urim5?ki-ma, aga3-kar2!(?E3)

urim='a agakar=?

GN=L2.NH defeat=ABS

be2-seg10S5b-S10i-S11n-S12sig-S14?

3.SG.NH-L2-3.SG.H.A-put-3.SG.P

“He defeated Ur.”

The second problem with Steible's interpretation is the meaning of the structure involving the first three words, if one analyses it as left-dislocated (= anticipatory)genitive construction:

(9)

?unir arawa=ak=ak ensik=be <*ensik ?unir arawa=ak=ak

“the ruler of the standard of Arawa”

Grammatically this analysis is correct, but the resulting meaning is odd: a city may have a ruler, but a standard may not. Steible's second translation (referred to as Steible [b] above), which is in conflict with his own grammatical analysis,may indicate that Steible himself had doubts in this translation.

The third problem with Steible's interpretation is his transliteration of the third line of the passage. He reads it as sa? mu-gub-ba in Ean. 1, 5 (= ABW Ean. 2), and 8 (= ABW Ean. 11); while he reads it as sa?-ba mu-gub-?ba? in Ean. 6 (= ABW Ean. 3-4). Foxvog, and Frayne follow Steible's transliterations,as does Selz in Ean. 8.41Cooper and Magid's translations are probably based on similar transliterations.

Kienast reads the line as sa?-ba mu-gub-ba,42Kienast 1980, 257.but assumes that the text omits the -ba at the end of the finite verb in Ean. 1, 5 and 8. Sollberger,43Sollberger and Kupper 1971, 58.Wilcke,44Quoted by Steible 1982, vol. 2, 65.and Edzard et al.45Edzard et al. 1977, 180.read the line as sa?-ba mu-?en.

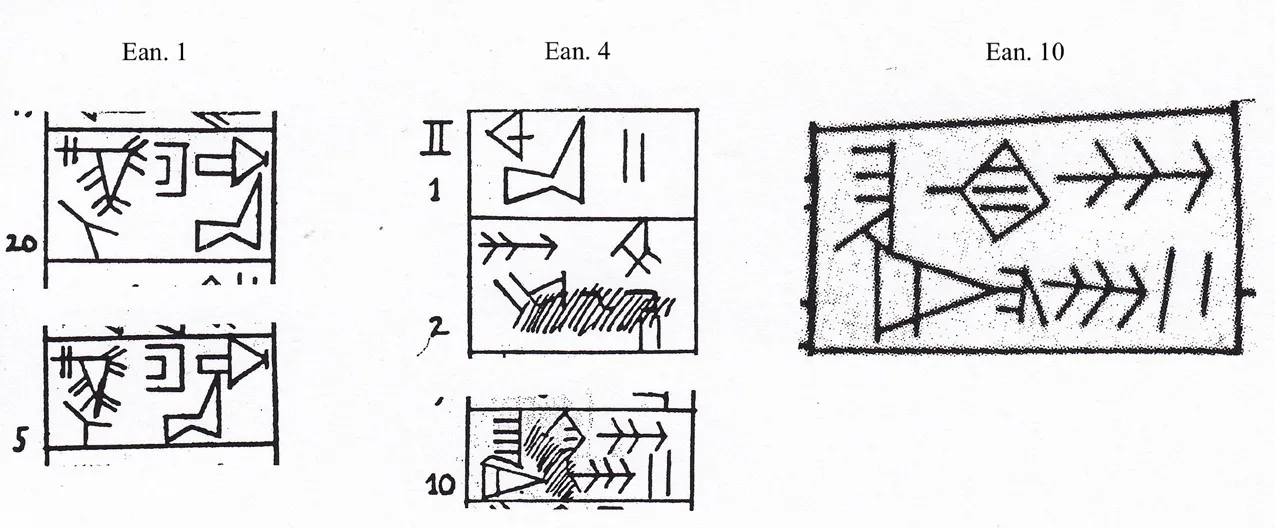

A look at the copies of Sollberger (see Fig. 1 above) suggests that the sign BA must be interpreted as attached to the word sa? “head,” but not as a writing of the subordinator suffix -/'a/ after an anticipated verbal stem gub. This is especially clear in the case of Ean. 1. Other inscriptions of E-ana-tum can also demonstrate that the subordinator suffix -/'a/ is always written with a sign that immediately follows the sign(s) used for writing the verbal stem, see Fig. 2 below for, e.g.,Ean. 1 (P222399) obv. 18:20 and 19:5 (nam e-ta-ku5-ra2) Ean. 4 (P222460)2:1 (ba-de6-a), 2:2 (mu-a-?lam-ma?-a), 2:10 (?u-na mu-ni-?gi4?-a); Ean. 10(P222469) 2:2 (?u-na mu-ni-gi4-a).46The lines of Ean. 1 and Ean. 4 are from Sollberger 1956, while the line of Ean. 10 is from Crawford 1977, 208.As Fig. 2 below shows, the signs in fact are not written in a random arrangement in E-ana-tum's inscriptions, refuting Steible's interpretation, which is based on the implausible assumption that the BA sign after the SAG sign in Ean. 1, 5, and 8 functions to write the subordinator suffix of the verb written with the sign DU.

Fig. 2: The writings of the subordinator suffix in E-ana-tum's inscriptions

The obscure sign after the sign DU in the only manuscript of Ean. 6 3:18 (E?EM 1595 = P222402) needs collation, and no interpretation may be based on it.

Here is a summary of the results of this section:

i) Steible's translation that considers the ruler as the defeated participant must be dismissed on the basis of the finite verbal form, whose prefix-chain indicates that the defeated verbal participant is non-human. And, consequently, none of the translations that take Arawa's ruler as the defeated participant may be correct.

ii) Steible's analysis of the first three words of the passage results in a semantically unsatisfactory translation.

iii) Steible, Selz, Frayne, and Foxvog's transliteration of the third line of the passage is supported neither by the actual arrangement of the signs nor by other occurrences of a finite verb followed by a subordinator suffix in E-ana-tum's inscriptions.

4. Wilcke's analysis and translation

The analysis and translation of Wilcke, which is quoted by Steible in his commentary to the passage in Ean. 5 (= ABW Ean. 2),47Steible 1982, vol. 2, 65.must be based on a transliteration like ex. (10):

(10)

?u-nir URU×Aki-ka, ensi2-be2, sa?-ba mu-?en …

“Das Emblem von URUxA - der Ensi dieser (Stadt) ging an der Spitze - (hat er mit [Waffen geschlagen]).”48Quoted by ibid.

He then analyses the orthographical form ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka as

(11)

?u-nir URU×Aki-ka

?unir arawa=ak='a

emblem GN=GEN=LOC

taking the locative case-marker as the case governed by the idiom aga3-kar2—sig10(for the case governed by this idiom, see also above).

It is fair to say that Wilcke's analysis and translation is one of the few translations of those listed above that does justice to the actual morphology and syntax of the passage. Nevertheless, one may raise two objections against it. One of them is semantic, the other one is syntactic by nature.

In Ean. 5 3:12-4:5, 6 3:11-4:9, and 8 3:5-5:2, the passage describing the defeat over Arawa's ruler is preceded by a passage about the defeat of Elam, and is followed by a passage about the defeat of Umma:

(12) Ean. 5 3:12-4:5, Ean. 6 3:11-4:9, Ean. 8 3:5-5:2

e2-an-na-tum2-e, elamur-sa? u6-ga, aga3-(?E3) be2-seg10, SAAR.DU6.

TAK4-be2, mu-dub, ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka, ensi2-bi sa?-ba, mu-DU, aga3-(?E3) be2-seg10, SAAR.DU6.TAK4-be2, mu-dub, ummaki, aga3-(?E3)be2-seg10, SAAR.DU6.TAK4-be220, mu-dub,dnin-?ir2-su-ra, a?ag ki a?2-ne2,gu2-eden-na, ?u-na mu-ni-gi4

“E-ana-tum defeated Elam, the marvellous mountain range and piled up a burial mound for it. He defeated ??? and piled up a burial mound for it. He defeated Umma, and piled up 20 burial mounds for it. He restored his beloved field of Gu-edena to Nin?irsu's control.”

Ean. 9 is an inscription on bricks that commemorates the building of a well of fired brick for Nin?irsu. It contains an abridged account of the conquests enumerated in ex. (12) above:

(13) E-ana-tum 9 2:4-11 (Q001063)

kur elamki, aga3-kar2!(?E3) be2-seg10, URU×Aki, aga3-kar2!(?E3) be2-seg10, ummaki,aga3-kar2!(?E3) be2-seg10

“(E-ana-tum) defeated the highlands of Elam. He defeated Arawa. He defeated Umma.”

The shortened account of Ean. 9 suggests that the structurally complicate passage under discussion should also mean that it is the city that is defeated.

In ex. (12) above, the passage is followed by the clause SAAR.DU6.TAK4-be2, mu-dub, “He (= E-ana-tum) piled up a burial mound for it (= the city).”Note that here the 3rd ps. sg. non-human possessive enclitic =/be/ (= “for it”)could not naturally be understood as referring to the city, if the preceding clauses were not meant to be about Arawa, but about its standard, as assumed by Wilcke.

The second objection to Wilcke's translation relates to its syntax. He assumes that there is a finite clause inserted between the finite verb formed from the idiom aga3-kar2— sig10and its semantic object case-marked with a locative case. In other words, there is a finite clause inserted as a kind of parenthetical remark in the middle of another finite clause. This structure is conceivable in a modern text,but its use is doubtful in a Sumerian royal inscription.

5. The translations without an analysis

The translations and analyses of Steible and Wilcke show that from the point of view of the grammar the most significant element in the interpretation of the passage is the syntactic function of the construction written as ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka.

Many of the translations and paraphrases interpret the “emblem of Arawa” as the object of the verb in the third line, understood as gub, “to put/place;” see the translations of Thureau-Dangin, Barton, Jacobsen, Sj?berg, Pongratz-Leisten,Szarzyńska, Michalowski, Potts, Kramer, Steible (b), Bauer (a), and Foxvog. The orthographical form of this construction, ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka, however, rules this interpretation out, as the construction has to be in a case different from the absolutive.

Two of the translations (Steible [a], R?mer) assume that the orthographical form represents ?unir arawa=ak=ak and the construction is a left-dislocated genitive whose possessum is ensi2-be2(?unir arawa=ak=ak ensik=be <*ensik ?unir arawa=ak=ak).49Note that reference of “dessen” in R?mer's translation is ambiguous; I assume that it refers back to the word “Emblem.”It has been shown above that this analysis leads to a semantically unsatisfactory translation.

Selz's translation disregards the morphology and syntax of the passage. It takes the ruler of Arawa as the head of the relative clause and assumes that the head (i.e.the ruler of Arawa) together with the succeeding relative clause is the possessor of the standard. This understanding would require a structure like ex. (14) below(assuming that the idiom aga3-kar2— sig10governs a locative2 case).

(14)

?unir ensik arawa=ak

emblem ruler GN=GEN

sa?=be='a

head=3.SG.NH.POSS=L1

S4mu-S10n-S12gub-S14?-S15'a=ak='a

VEN-L1.SYN-stand-3.SG.S-SUB=GEN=L2.NH

“Das F?hnlein des Stadtfürsten von Arawa, der (pers?nlich) an dessen Spitze stand, (hat er mit Waffen geschlagen).”50Selz 1991, 34.

Cooper, Magid, and Frayne translate the verbal form of the third line as an intransitive verb, “stood,” whose subject is the ruler; and translate ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka as “with the (city's) emblem.” They thus most probably assume that the construction is in the locative1 case (?unir arawa=ak='a = emblem GN=GEN=L1). The locative1 may indeed “denote the verbal participant which functions as the material with which a verbal action is carried out,”51Zólyomi 2017, 205.but, at least in the 3rd millennium BC, is not used to mark the instrument of a verbal action.

6. Towards a solution

Joachim Krecher used to say jestingly in his classes that if you have a Sumerian sentence with the words “bird,” “tree,” and “sit,” then you can be 100 % sure that the sentence means “A bird sits on the tree” and not “A tree sits on the bird.”It appears that many of the translations listed at the beginning of this paper were prepared by applying a similar principle: their authors tried to translate an obscure Sumerian construction by taking into account only its words' meaning,while basically neglecting verbal and nominal morphology and / or syntax.

This principle may work with sentences like the one quoted, but is doomed to result in inaccurate translations when the relation among the entities involved is less predictable. In the remaining part of this paper therefore a new translation will be offered, which takes into consideration not only morphology and syntax,but also the information structure of the passage.

Our starting point is the meaning of the expression sa?-ba/be2-a — DU, in which the word sa? “head” is in the locative1 case. In literary texts, the expression appears to have two main uses:

i) It may be used in connection with a divine utterance, and then its meaning is something like “foremost, pre-eminent,” see exx. (15)-(20) below. In this meaning, it is used as a synonym of the phrase sa?-be2-?e3— e3, see, for instance, ex. (21) below.

ii) It may refer to someone or something who/which goes ahead of a group of people or objects in a procession, see exx. (22)-(25) below. In this meaning,the 3rd ps. sg non-human possessive enclitic =/be/, attached to the word “head,”appears to refer to the group ahead of which the subject of the verb goes. This meaning of the expression may also be paraphrased as “to lead:” X goes ahead of Y = X leads Y.

(15) ?ulgi R 70 (ETCSL 2.4.2.18)

nam tar-ra-a-be2ul-le2-a-?e3ni?2sa?-ba du-am3

“an allotted fate to be pre-eminent forever”

(16) ?ulgi Y 6 (ETCSL 2.4.2.25)

dutu inim-ma-ne2sa?-ba du ma?kim-?e3ma-an-?um2

“He assigned Utu, whose words are pre-eminent, as a constable to me.”

(17) I?me-Dagan H 24 (ETCSL 2.5.4.08)

“your august utterances are prominent”

(18) Letter from Kug-Nanna to the god Nin?ubur 5 (ETCSL 3.3.39)

dug4-ga-ne2sa?-ba du

“(the god) whose words are pre-eminent”

(19) Damgalnuna A 6 (ETCSL 4.03.1)

en gal-an-zu dug4-ga-ne2sa?-ba du kug-zu ni?2-nam-ma-kam

“the sage lord whose command is foremost, who is skilful in everything”

(20) CUSAS 17, 53 3 (P252230)

?dug4?-ga-ne2sa?-ba du

“(An) whose words are pre-eminent”

(21) Gudea Cyl. A 4:10-11 (ETCSL 2.1.7)

dnan?e-?u10dug4-ga-zu zid-dam, sa?-be2-?e3e3-a-am3

“My Nan?e, what you say is trustworthy and takes precedence.”

(22) Gudea Cyl. B 15:21-22 (ETCSL 2.1.7)

bala? ki a?2-ne2u?umgal kalam-ma, sa?-ba ?en-na-da

“to see that his beloved drum U?umgal-kalama will walk in front (of the

procession)”

(23) ?ulgi R 51 (ETCSL 2.4.2.18)

ur-sa?den-lil2-la2dnin-urta sa?-be2-a mu-?en

“Enlil's warrior, Ninurta, went ahead of them (= Ninurta's divine weapons).”

(24) Lugalbanda in the mountain cave Segment A 35-38 (ETCSL 1.8.2.1)52See now the translation of these lines by Wilcke (Volk 2015, 229), which must be based on a new text as the manuscript on which the ETCSL edition of these lines was based (HS 1479 = P345605),is fragmentary here: “Ihr Gebieter, wie er an ihrer Spitze schritt, / War eine die Truppe anzischende Pfeilnatter. / Enmerkar, wie er an ihrer Spitze schritt, / War eine die Truppe anzischende Pfeilnatter.”

?lugal?-be2sa?-ba du-a-ne2, X X X erin2-na-ka di-dam

?en?-[me-er-kar2?-ba du-a-ne2,? […]-?ka? di-dam

“When their king went ahead of them (= the mobilized people of Uruk), it was

… of the army; when Enmerkar went ahead of them, it was… .”

(25) Nin?i?zida A 28 (ETCSL 4.19.1)

lugal ni2ri-a ildum2ud-be2sa?-ba du-a

“king endowed with awesomeness, sun of the masses, advancing in front of them”

The uses of the expression sa?-ba/be2-a — DU discussed above are in disagreement with the established interpretation of Gudea Cyl. A 14:26-27 (and of the similar passages in Cyl. A 14:16-18 and 14:21-23).53Cf. also the latest translation by W. Heimpel (Volk 2015, 133): “Er stellte die Scheibe, die die Standarte Inannas ziert, zu ihre H?upten.”As mentioned above,Steible too referred to these texts for his interpretation of the passage under discussion:

(26) Gudea Cyl. A 14:26-27 (ETCSL 2.1.7)

im-ru-adinana-ka zig3-ga mu-na-?al2, a?-me ?u-nirdinana-kam sa?-bi-a mu-gub

“Im Imru'a der Inanna veranstaltete er ihm (= Ningirsu) ein Aufgebot. Die

‘Scheibe' (= A?.ME) - es ist das Emblem der Inanna - stellte er davor.”54Steible 1982, vol. 2, 64-65.

Many of the translations listed in the first part of this paper were obviously adjusted according to the established interpretation of the Gudea passages. This explains that some of the translators wanted to see the BA sign of the third line as part of the finite verb, permitting only the gub reading of the verbal base.

In fact ex. (26), and the similar passages, may well be translated differently,in accordance with the second use of the idiom sa?-ba/be2-a — DU: “There was a levy for him on the clans of Inana …, the rosette, the standard of Inana,went in front of them (= the clans);”55For the attributive translation of the copular clause in this example, see Zólyomi 2014, 69-81. Cf. J.Dahl's interpretation of this passage on CDLI (P431881, l. 385). He transliterates the verbal form as mu-gen and translates the line as “[t]he sun-disk, it is the emblem of Inanna, went at its head.”assuming that the verbal form is mu?en, which can then be analysed asS4mu-S10n-S12?en-S14? = VEN-L1.SYN-go-3.SG.S; the syncopated locative1 prefix would cross-reference the word sa?-be2-a in the locative1 case.56When the locative1 prefix /ni/ forms an open unstressed syllable, then the vowel of /ni/ becomes syncopated, and the prefix is reduced to /n/; see Zólyomi 2017, 203.Note that also in ex. (22) above, where the ?en reading of the verbal base is unquestionable, an object is meant to “walk,” and is not, for example, “carried.”

One may also mention that “to erect” a standard (?u-nir) is in fact expressed with the verb sig9“to place” in Gudea Cyl. A 26:3-5, and with the verb du3“to erect” in ?ulgi D 178 (ETCSL 2.4.2.04),57This line is preserved in two manuscripts. In CBS 11065 + N3202 rev. 2':11' (= P266239), the verbal form is ?ga-am3?-du3; in Ni 4571 obv. 1:32 (P343096) it is ga-am3-du11; du11 is probably a phonetic writing for du3. ETCSL transliterates the verbal form erroneously as ga-am3-gub.but not with the verb gub. In ?ulgi E 220 (ETCSL 2.4.2.05), “to carry” a standard is expressed with the verb il2“to carry.”

In the E-ana-tum passage under discussion, repeated here in a slightly modified form as ex. (27) below, obviously the second use of the idiom sa?-ba/be2-a — DU is relevant.

(27)

?u-nir URU×Aki-ka, ensi2-be2,

?unir arawa=ak=ak ensik=be=?

emblem GN=GEN=GEN ruler=3.SG.NH.POSS=ABS

sa?-ba mu-?en

sa?=be='aS4mu-S10n-S12?en-S14?

head=3.SG.NH.POSS=L1 VEN-L1.SYN-go-3.SG.S

aga3-kar2

!(?E3) be2-seg10

agakar=?S5b-S10i-S11n-S12sig-S14?

defeat=ABS 3.SG.NH-L2-3.SG.H.A-put-3.SG.P

Steible and R?mer considered the first two words (?unir arawa=ak=ak) a leftdislocated genitive whose possessum is the ruler (ensi2). Alternatively, one may assume that the possessum of this left-dislocated genitive is the word “head” (sa?),and that the 3rd ps. sg. non-human possessive enclitic =/be/ of ensi2refers to the city, Arawa, as also assumed by Sollberger and Kienast.58Cf. Gudea Cyl. A 17:17, where similarly a left-dislocated possessor and its possessum are separated by another participant of the clause, its agent (den-ki-ke4).

Many of the previous translations consider the first part of the passage a relative clause. The translations then differ in which participant they choose to be the head of this relative clause. In a relative clause, the finite verb of the third line would have to be suffixed with a subordinator suffix /'a/. The orthography of this line, however, indicates clearly that we cannot have here a subordinate verbal form: one expects here the preterite form of the verb “to go,” which would be written as mu-?en-na as the predicate of a relative clause.

All these assumptions would then lead to the following translation of the passage:

Literally: “Arawa's standards, its ruler marched ahead of them, he (= E-ana-tum)defeated it (= Arawa).”

= “(Although) its ruler marched ahead of Arawa's standards, he (= E-ana-tum)defeated it (= Arawa).”

Some explanatory remarks, first about its structure. It would perhaps sound better in English: “(Although) Arawa's ruler marched ahead of its standards,he (= E-ana-tum) defeated it (= Arawa).” The first version reflects better the Sumerian, in which the possessor of the ruler is pronominalized. It is pronominalized because the name of the city is placed in front of the whole passage as part of the left-dislocated genitive construction ?u-nir URU×Akika. In other words, it is topicalized, and participants already topicalized will be referred with a pronominal expression in Sumerian. In the second clause of ex.(28) below, the temple is, for example, referred to by the 3rd ps. sg. non-human possessive enclitic =/be/.59Cf. Zólyomi 2005, esp. 171.

(28) Gudea Cyl. A 29:14-17 (ETCSL 2.1.7)

e2-a ni2gal-be2

e=ak ni gal=be=?

house=GEN fear great=3.SG.NH.POSS=ABS

kalam-ma mu-ri

kalam='aS4mu-S10n-S12ri-S14?

land=L1 VEN-L1.SYN-put-3.SG.S

ka-tar-ra-be2kur-re

katara=be=? kur=e

praise=3.SG.NH.POSS=ABS mountain=DAT.NH

ba-te

S5b-S7a-S12te-S14?

3.SG.NH-DAT-reach-3.SG.S

“The temple's great awesomeness settles upon the Land, its praise reaches to the highlands.”

The hypothetical ex. (29) below would be an alternative way to express the grammatical relations of the first clause of ex. (27), the actual text. In this version, however, the pronoun would be before the noun (Arawa) that should function as its antecedent. Also, the city's name would not be in a topical position in this version, so it could not function as the topic of the second clause of the passage, i.e., the second clause could not effortlessly be interpreted as being about the city. In other words, ex. (29) would probably be ill-formed from the point of view of information packaging.

(29)

*?unir=be=ak ensik arawa=ak=?

emblem=3.SG.NH.POSS=GEN ruler GN=GEN=ABS

sa?=be='aS4mu-S10n-S12?en-S14?

head=3.SG.NH.POSS=L1 VEN-L1.SYN-go-3.SG.S

Yet another way to express the grammatical relations of the first clause of ex.(27) would be a construction in which the possessor of the already left-dislocated genitive construction (?unir arawa=ak=ak … sa?=be='a) is also left-dislocated as in the hypothetical ex. (30) below.

(30)

*arawa=ak ?unir=be=ak

GN=GEN emblem=3.SG.NH.POSS=GEN

ensik=be=? sa?=be='a

ruler=3.SG.NH.POSS=ABS head=3.SG.NH.POSS=L1

S4mu-S10n-S12?en-S14?

VEN-L1.SYN-go-3.SG.S

A similar construction is attested in Gudea Cyl. A 6:1-2, see ex. (31)below, where the first line of the example is a doubly left-dislocated double genitive construction, that may be derived from an underlying mul kug [du[e=ak]=ak]='a.60For an analysis of this example, see Zólyomi 2017, 55.

(31) Gudea Cyl. A 6:1-2 (ETCSL 2.1.7)

e2-a du3-ba

e=ak du=be=ak

house=GEN building=3.SG.NH.POSS=GEN

mul kug-ba

mul kug=be='a

star holy=3.SG.NH.POSS=L2.NH

gu3ma-ra-a-de2

gu=?S4mu-S6r-S7a-S10e-S12de-S14e

voice=ABS VEN-2.SG-DAT-L2-pour-3.SG.A

“She will announce to you the holy stars of the building of the temple.”

One can only speculate why our texts do not use the construction of ex. (30),in which Arawa would be even more topical at the beginning of the clause. As a matter of fact, ex. (31) is the only occurrence of the doubly left-dislocated double genitive construction in the whole corpus of Sumerian texts, attested in a literary text, so it may not have been a real option. Note also that the leftdislocated possessors and the possessum follow each other in ex. (31), while in the hypothetical (30) there would be another noun with a 3rd ps. sg. nonhuman possessive enclitic (ensik=be=?) between the left-dislocated possessors(arawa=ak ?unir=be=ak) and the possessum (sa?=be='a). Would the interpretation of (30) be too ambiguous, and hence the construction is to be avoided? We cannot know. These are the subtleties of Sumerian grammar that may never be retrieved without native speakers.61Cf. the pertinent observation of W. Labov (1994, 11): “… historical documents can only provide positive evidence. Negative evidence about what is ungrammatical can only be inferred from obvious gaps in distribution, and when the surviving materials are fragmentary, these gaps are most likely the result of chance.”

As regards the meaning of the passage, all previous translators translated the construction ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka in singular: “the standard/emblem of Arawa.”Non-human words, however, may not use the plural enclitic =/enē/ in Sumerian,their plurality is as a rule not marked overtly. The construction may therefore well be translated in plural. One may then assume that the expression “Arawa's standards” refers metonymically to the people of a city state mobilized and organized into groups, similarly to the description in Gudea's Cylinder.62Cf. Michalowski et al. 2010, 107: “The archaeological evidence … indicates that during the earlier Early Dynastic period Deh Lurān was the location of a small and compact hierarchically organized polity centred on Tepe Musiyān with several subsidiary towns … and a number of dependent villages.” As regards the function of standards, they mention (ibid.) that “Szarzyńska (1996) has shown that standards placed or carried on a pole have represented institutions and polities from at least 3200 B.C.”

This assumption would then also explain why E-ana-tum thought it important to add this passage to the description of his victory over Arawa. He boasts that although the whole city-state was mobilized and led to war by its ruler, yet he was able to defeat it.

This translation is then in agreement with Bauer's understanding of the passage, who gave the following “free” translation, without, however, offering a grammatical analysis of the passage: “Obwohl der Ensi der Stadt URU×A eine Generalmobilmachung veranstaltete, schlug Eanatum ihn trotzdem.”63Bauer 1998, 457.The interpretation proposed in this paper differs only in the participant defeated.Bauer thought it to be the ruler, this paper has argued that it has to be the city.

7. Summary

This paper has its origin in dissatisfaction with the existing translations and analyses of a passage in E-ana-tum's inscriptions, read and translated now as follows:

?u-nir URU×Aki-ka, ensi2-be2, sa?-ba mu-?en, aga3-kar2!(?E3) be2-seg10

“(Although) its ruler marched ahead of Arawa's standards, he (= E-ana-tum)defeated it (= Arawa).”

The new translation is based on the following considerations:

i) The idiom aga3-kar2— sig10, “to defeat” case-marks the “defeated”participant with the locative2 case. The prefix-chain of the finite verb in the second clause contains a composite 3rd ps. sg. non-human locative2 prefix,indicating that the defeated participant may not be the ruler of Arawa, as assumed by many of the translations.

ii) The actual arrangement of the signs in the third line of the passage, and other occurrences of a finite verb followed by a subordinator suffix in E-ana-tum's inscriptions indicate that the BA sign must be interpreted as attached to the word sa? “head” in this line, but not as a writing of the subordinator suffix -/'a/after an anticipated verbal stem gub, as assumed by many of the translators,except of Sollberger and Wilcke.

iii) The idiom sa?-ba/be2-a — DU means “to proceed/go/walk ahead of someone / something,” as attested in several literary texts. The DU sign therefore stands for the lexeme ?en, “to go.” The first part of the passage is not a relative clause but a finite clause ending with the verbal form mu-?en, as already assumed by several of the translators.

iv) The orthographical form ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka stands for a left-dislocated genitive (= ?unir arawa=ak=ak) whose possessum is the word sa?, “head,” as assumed also by Sollberger and Kienast.

v) The shortened version of the description of E-ana-tum's victories in E-anatum 9 2:4-11 suggests that the defeated participant must be the city, Arawa,but not its standard, as assumed by Wilcke, R?mer, Selz, and Foxvog.

vi) The expression ?u-nir URU×Aki-ka may be translated in plural as “Arawa's standards,” and it refers metonymically to the people of the city-state mobilized and organized into groups because of the war, an assumption that appears to underlie Bauer's (b) interpretation.

This paper has also meant to demonstrate that translations of Sumerian texts from the 3rd millennium BC may not rely solely on the meaning of the words, they have to be based on an analysis of syntax and morphology. Our understanding of these areas of Sumerian grammar has improved greatly in the last decades, and these improvements should not be left out of consideration.

Bibliography

Barton, G. A. 1928.

The Royal Inscriptions of Sumer and Akkad. Library of Ancient Semitic Inscriptions. New Haven, CT: The Yale University Press.

Bauer, J. 1998.

“Der vorsargonische Abschnitt der mesopotamischen Geschichte.” In: J. Bauer et al. (eds.), Mesopotamien. Sp?turuk-Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 160/1. Fribourg & Gottingen: Editions Universitaires &Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 431-585.

Chavalas, M. W. (ed.). 2006.

The Ancient Near East. Historical Sources in Translation. Blackwell Sourcebooks in Ancient History. Malden, MA et al.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Cooper, J. S. 1986.

Sumerian and Akkadian Royal Inscriptions. vol. 1. The American Oriental Society. Translation Series 1. New Haven, CT: The American Oriental Society.

Crawford, V. E. 1977.

“Inscriptions from Lagash, Season Four, 1975-76.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 29: 189-222.

Edzard, D. O. et al. 1977.

Répertoire Géographique des Textes Cunéiformes. vol. 1: Die Orts- und Gew?ssernamen der pr?sargonischen und sargonischen Zeit. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients Reihe B 7/I. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

Frayne, D. 2007.

Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC). Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods 1. Toronto et al.: University Press of Toronto.

Jacobsen, Th. 1967.

“Some Sumerian City-Names.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 21: 100-103.

Jagersma, A. H. 2010.

A Descriptive Grammar of Sumerian. PhD-dissertation: Universiteit Leiden,accessed under: https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/16107(01.04.2018).

Kaiser, O. et al. (eds.). 1984.

Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments. vol. 1/4: Historisch-chronologische Texte I. Gutersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus Gerd Mohn.

Kienast, B. 1980.

“Der Feldzugsbericht des Ennadagān in literarhistorischer Sicht.” Oriens Antiquus 19: 247-261.

Kramer, S. N. 1963.

The Sumerians. Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Labov, W. 1994.

Principles of Linguistic Change. vol. 1: Internal Factors. Language in Society 20. Oxford & Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Michalowski, P. et al. 2010.

“Textual Documentation of the Deh Lurān Plain: 2550-325 B.C.” In: H. T.Wright and J. A. Neely (eds.), Elamite and Achaemenid Settlement on the Deh Lurān Plain: Towns and Villages of the Early Empires in Southwestern Iran.Memoirs of the Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan 47. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan, 105-112.

Molina, M. 2015.

“Urua.” Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Arch?ologie 14/5-6:444-445.

Pongratz-Leisten, B. 1992.

“Mesopotamische Standarten in literarischen Zeugnissen.” Baghdader Mitteilungen 23: 299-340.

Potts, D. T. 2016.

The Archaeology of Elam. Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. 2nd ed. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Selz, G. J. 1991.

“‘Elam' und ‘Sumer' - Skizze einer Nachbarschaft nach inschriftlichen Quellen der vorsargonischen Zeit.” In: Mesopotamie et Elam. Actes de la XXXVIème Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale Gand, 10-14 juillet 1989.Mesopotamian History and Environment. Occasional Publications 1. Ghent:University of Ghent, 27-43.

Sj?berg, ?. W. 1967.

“Zu einigen Verwandtschaftsbezeichnungen im Sumerischen.” In: D. O. Edzard(ed.), Heidelberger Studien zum Alten Orient. A. Falkenstein zum 17. September 1966. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 201-231.

Sollberger, E. 1956.

Corpus des inscriptions “royales” présargoniques de Laga?. Genève: Libraire E.Droz.

Sollberger, E. and Kupper, J. R. 1971.

Inscriptions royales sumeriennes et akkadiennes. Literatures anciennes du Proche-Orient 3. Paris: Les éditions du Cerf.

Steible, H. 1982.

Die altsumerischen Bau- und Weihinschriften. vol. 1-2. Freiburger altorientalische Studien 5-6. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Steinkeller, P. 1982.

“The Question of Marha?i: A Contribution to the Historical Geography of Iran in the Third Millennium B.C.” Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 72: 236-265.

Szarzyńska, K. 1996.

“Archaic Sumerian Standards.” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 48: 1-15.

Thureau-Dangin, F. 1907.

Die sumerischen und akkadischen K?nigsinschriften. Vorderasiatische Bibliothek 1/1. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung.

Veldhuis, N. 2010.

“Guardians of Tradition.” In: H. D. Baker et al. (eds.), Your Praise is Sweet. A Memorial Volume for J. Black from Students, Colleagues and Friends. London:BISI, 379-400.

Volk, K. (ed.). 2015.

Erz?hlungen aus dem Land Sumer. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Zólyomi, G. 2005.

“Left-dislocated Possessors in Sumerian.” In: K. é. Kiss (ed.), Universal Grammar in the Reconstruction of Ancient Languages. Studies in Generative Grammar 83. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 161-188.

——2010.

“The Case of the Sumerian Cases.” In: L. Kogan et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the 53e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. vol. 1: Language in the Ancient Near East (2 parts). Babel und Bibel 4A-B. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns,577-590.

——2014.

Copular Clauses and Focus Marking in Sumerian. Warsaw & Berlin: De Gruyter Open.

——2017.

An Introduction to the Grammar of Sumerian. With the Collaboration of S. Jáka-S?vegjártó and M. Hagymássy. Budapest: E?tv?s Kiadó.