The Meaning and Madness of Money: A Semio-Ecological Analysis

Per Aage Brandt

Case Western Reserve University, USA

The Meaning and Madness of Money: A Semio-Ecological Analysis

Per Aage Brandt

Case Western Reserve University, USA

In this paper, I propose an overall model of the semantic and semiotic functions of money and capital forms, based on an ecological view of human activity and a theory of the origin of money (coined precious metals). Themeaningof money is replaced in a structured human perspective, and a critical discussion is outlined on the grounds of the material and capital flows and functions identified. Themadnessof money follows from the separation of economy and ecology. That madness causes serious damage, especially under certain circumstances that the structural analysis can identify. Finally I add some new considerations on the psycho-semiotic implications of the analysis. The societal structure discussed can be interpreted in terms that have strikingly direct correspondence to those describing semiotic aspects of language and the human psyché, where the concepts of meaning and madness are immediately pertinent.

semio-ecology, money origins, socio-semiotics, the money sign, the symbolic order

1. Ecological Prerequisites

Monetary signs not only ‘signify’ abstract value but also possess a performative force rooted in their substantiation, that is, rooted in the fact that theirsubstanceof expression, to use the linguist Louis Hjelmslev’s term, is, at least in their basic manifestation as coins,but even still in their indirect manifestations, singularized as material objects.1Their“form of expression” cannot be separated from their “substance of expression”. The act of ‘giving signs’ is normally participative (the giver does not ‘lose’ what he gives, he just shares it), whereas giving money, therefore, isseparativegiving (moving singular material objects from one proprietor to another). This unique condition of monetary signs—money and its generalization: capital—is therefore still a serious challenge to semiotic theory. The understanding of performative force in speech acts offers a similar difficulty,based on their ritual abolition of the distinction between sign and thing in illocutionary uses of language.2Economics, the mathematics of monetary practices, is of little help in treating this challenge, in so far as it builds on the assumption that this mysterious object condition of the existence of money signs simply holds by definition; it is taken as an axiom, which should not be explained but just taken for granted and then analyzed in its current contexts.3

In this essay, I will present an alternative, namely a semiotic and ecological, or semioecological, view of the problem of understanding money. I will ignore the axiom that the existence of money should just be taken for granted, and instead start from basic ecological considerations, supplemented by a semiotic approach to the issue.

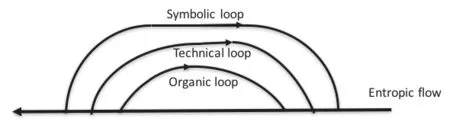

As the French philosopher Georges Bataille pointed out in a metaphysical moment,the living nature and the existence of human civilizations, are results of the practically infinite, generous, unrequited, entropic ‘giving’ of the sun, which on our planet causes anegentropicprocess calledlife.4If we follow Bataille and think of the entropic temporal flow of matter and energy as one immense stream, we may imagine the negentropic movement that humans and all other living beings are involved in, as a local reverse stream, or rather a number of local reverse negentropic streams, branching off from the main entropic flow. These negentropic streams finallyreturnto the main, entropic flow and thus form anecological loop. The return happens because death, decay, and waste make these negentropic movements spatially and temporally finite; new negentropic processes must start from the local death, decay, and waste of the former processes. This ecological loop is therefore never a trivial given; life is fragile and abruptly ends if it cannot feed on a nature that includes life’s own litter.

Fig. 1. A negentropic loop

Entropy universally increases, but locally decreases where living matter emerges. Life thus consists in a loop by which the universal run towards chaos is momentarily halted and patterns of organization grow, until death and decay resume the universal tendency.This is the elementary general framework I suggest as a general prerequisite of the development of a semio-ecological analysis. When life emerges, it lays the ground for organic species, and again for human life, which feeds on life in general, and on life’s decay and litter. In the case of humans, however, from the moment civilizations emerge,an empirical analysis easily distinguishes three principal (sub-negentropic) off-branchings and sub-loops, corresponding to three standard levels of social organization. We can in fact superimpose three negentropic sub-loops in the case of human civilizations.

A first ecological sub-loop is initiated by our direct extraction and consumption of organic matter and water: vegetables, fruits, crops, animals—elements whose preparation mainly presupposes access to soil, water, wind, and fire, and a certain technique—hunting, fishing, gathering, sheltering, and then agriculture. This basicorganic loophas its own ecology, of course; crops must be kept growing on viable qualities of soil, and so on. Water, soft or salt, must be kept clean enough to remain a fishing environment or a source of watering and drinking. Firewood must be renewable. Deterioration and devastation are always threatening possibilities. Civilizations are ecologically vulnerable,as ethnology shows. Basic ecological consciousness, as found in tribal societies, grows on this essentialorganicloop, and may extend to the following two loops.

A second loop extracts energy and raw materials allowing further elaboration of provisions, securing life conditions, and creating tools and means to satisfy expanding functional needs of collective life: we may call it thetechnical loop. Systematic production and distribution of artefacts (tools, machines, ships, weaponry) and other complex goods thus require extendedextractionof energy, stone, iron, wood, building materials, raw materials for all kinds of production and construction: production facilities,infrastructure (roads, bridges, means of transportation and communication), social institutions, marketplaces, shops and workshops, homes and urban settings. Technical production, maintenance, repair, renewal, and development of the entire space of work and exchange, increase the consumption of energy and many sorts of material. Strategies for the disposal and treatment of waste and refuse are again never trivial in view of maintaining a local habitat and a local population’s health and growth. The technical loop differs from the organic loop by its most prominent effect, urbanization, with its dumping sites and cemeteries.

Finally, a third,symbolic loopalways extracts exquisite elements from nature for transcendent ‘spiritual’ reasons: precious and rare metals and minerals, gold, silver, copper,marble, jade, gemstones, are extracted for decorative and symbolic uses related to the erection of palaces and temples, with their adornments, imagery and statues, monuments,that is, for ceremonial purposes of many kinds, sacred or profane. In all larger historical societies, religious or profane displays of social power constitute an overall category ofsymbolicconstructivity and activity that shapes social life by providing overarching authority, mythology, emotional coherence, bringing both mystery and principles of ‘value’and forms of legitimacy—forms of ‘beauty’, ‘truth’, ‘justice’, and ‘morality’—to the entire complex of practices implied by collective life.5Taking care of the need for collective identity is an essential symbolic task of the nominal ruler, the sovereign. Taking care of deaths, births, and individual or collective alliances, is an essential symbolic task of the religious category. So we may call this particular stream thesymbolic loop. Symbolicity culturally seals the social formation as a whole. The negative output, or product, of the symbolic loop includes aggressive ideology and its consequence, warfare and destruction.In the contemporary world civilization, the symbolic loop still involves imagery and behaviors expressing the typical ‘spiritual’ endeavors embodied in sovereignty, and religion.

These three negentropic, looping streams, all branching off from the main entropic flow and returning to it, can be represented as superimposed levels ofsubstantial and formal social life. The substantial differences from level to level will correspond to formal differences in the regulations and concepts appearing at the three levels. I hypothesize that the stratified flow model thus obtained is, so far, generally valid for human social formations throughout our prehistorical and historical civilizations, whether huntergatherer-tribal, agricultural-feudal, agri-theocratic, capitalo-industrial, or otherwise formalized.

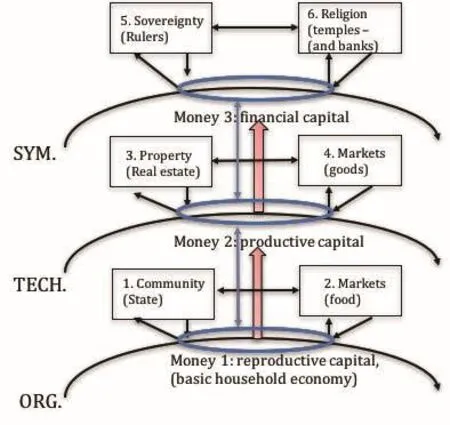

Fig. 2. The organic, the technical, and the symbolic loops on the entropic flow

The three extraction-based loops will further correspond to three levels of vital social activity and life forms: in a very elementary social formation, that oforganic producers:agents in agriculture, fishing, hunting, gathering, etc.; that oftechnical producers:craftsmen, workers, engineers, administrators, traders, social and commercial agents; and that ofsymbolic producers: chiefs, rulers, politicians, intellectuals, artists, priests, and bankers.

Between the three loops, there will always be many sorts of exchange, especially of products from one level serving on another level, both upwards and downwards. It is further necessary to consider the institutions that the constant activities on each level and between them create, as if by sedimentation, and which slowly but surely emerge by the nature of things, namely the needs that the activities themselves generate: needs for norms and maintenance of means, moral and technical. We can consider them as the modes ofstasisalong or within the flows, and it is possible to postulate a finite set of such major categories ofstasis,or‘establishments’—which may differ in many ways and in their relative importance, depending on the specific structures developed in specific cultures and forms of social production. Here follows my suggested list of default instances of this kind: six elementary categories of stasis.

(1) Firstly, things like assuring the access to water, shelter, protection, construction wood and firewood, a territory of operation, require concrete collaborative measures,certain elementarycommunitarysystemsfor sharing necessary burdens and possible outcomes. This is the rudiment that may evolve into the network of institutions we now call the modern nation State. The elementary communitary instance primarily connects and interacts with the organic and the technical flows.

(2) Secondly, organic products are immediately exchanged and distributed within a population according to some principles allowing the sharing of food, services, and basic goods. A community must therefore create and maintain pathways and places, where transportation, presentation and exchange of such entities can happen. We may call such accessible places, in a very elementary sense, foodmarkets.

(3) Thirdly, as mentioned, we may acknowledge the stasis of urbanization, the creation of cumulative habitats where systematic technical production and products (artefacts)can be sheltered and connected (workshops, factories, storages), and where larger-scale social and cultural communication can happen. This ‘public’ sphere of urbanized activity includes the social accumulation of material goods and corresponding ‘wealth’, and the display thereof. Material wealth in turn leads to the development of abstract juridical concepts of property: principles of ownership, ‘private’ or ‘public’, passed down through generations and expressed by real estate; legal charters that allow private interests to emerge within the public domain.6

(4) Exchanges on the level of ‘property’ lead to higher orders of distribution and market formation. On this level, real estate, land, and human beings (workers, women,slaves) are among thegoodsexchanged. The modern labor market is one of the aspects of this instance of the market; but much else is of course bound to happen before we get that far. This level is where production becomes industrial and capitalistic in the basic sense,and where the marxian theory of Capital, surplus value, profit, and subsequent class struggle then relevantly applies. Here is where societies acquire their so-called political economies, to be distinguished from their ‘general economies’ in Bataille’s sense, which includes all three levels.

(5 and 6) On the third stream, the symbolic one, there are two universally unfolding forms of stasis. One is what we call the instance ofsovereignty, the place and institution of the ruler, the incarnation of the privilege and physical power to make binding decisions for entire populations on a territory and to declare wars: to define a ‘country’, and later,a ‘nation’, or even an ‘empire’. Physically, this stasis is expressed by lavish buildings, displays of provocative architecture with monumental dimensions and emphatic use of extracted and preferably rare and costly materials. The other form is the materialization ofreligion, the equally provocative and awe-inducing temple, which in modern societies,especially after the introduction and generalization of the use of money, is doubled by a parallel variant, the bank.7

The following graph summarizes this simplified analysis of stases in the formation of a shared human reality. There is of course much more interaction between these instances than shown by the arrows of the graph. The idea is that an elementary deep-structure like the one proposed here must underlie the specification of distinct social formations,modes of production, and politico-economic structures and conjunctures, making them comparable. The contrasts between an isolated tribal society and a modern industrial society are evidently huge, but my claim is that we need a materialistic, ‘pre-structured’ecological basis like the one sketched out in this model to be able to structurally and more precisely specify and understand the differenthistoricalformations. History would thus be the temporal unfolding of a largely pre-determined structure.

Fig. 3. Three strata and six stasis categories in the formation of social reality

The three basic streams articulate the presupposed human population, a part of which is mainly active on the organic level, whereas other parts are active on the technical level of production; a much smaller part is active on the symbolic level, where power and sacredness are fabricated. Hence the intuitive model of a society as a pyramid. A population8will become a class or caste society if the level of activity, in terms of strata,of one generation is transferred to and thus inherited by subsequent generations. The access or non-access to property and sovereignty is then of course particularly important to the social status of a population segment. And as Marx and Engels stated, theextension of private ownershipof collectively produced products is one of the preconditions of the formations we call capitalistic. However, a prerequisite of the same magnitude is the existence and functionality ofmoney.

2. Money

There are reasons to believe that the phenomenon and the extended use of money, in the form of coins, emerge during the so-called Axial Age9, and that the religious instance (6,above) is directly involved.10Precious materials and, in particular,metalsare first used for the adornment of iconic representations of rulers and divinities (statues, imagery).These metals, gold, silver, electrum, bronze etc., are thereby—namely through the magical contact with the artistically embodied sacred entity—rendered even more precious, and are then, we suggest, interpreted as inheriting and containing the power of the divinities they adorn and magically touch. The priests discover that they can make poeple work for them by ‘paying’ them with these metallic items. Then the priests can‘lend’ people certain quantities of them for similar purposes, but against mortgage.They acquire an inherentprotective value11that makes them desirable in social life,in the shape of artistic adornments, and then in the shape of smallcoinscarrying the signs of a ruler who may in principle be seen as guaranteeing their metallic authenticity and volume. The ascribed inherent ‘value’ of pieces of such metal of equal weight and authenticity is then relatively equal and stable. The temple is originally the place where such money is coined and issued, and where larger quantities or amounts of ‘monetary’value is kept, hence the historical link between (ancient) temples and (modern) banks.But of course, the efficiency of these shining items is proven outside the temples, and especially in marketplaces on lower social levels. The use of uniform metallic units containing the abstract, imaginary property ofprotectingits owner is reinforced by the practical demonstration: in fact, the more you acquire of these entities, the better off you are.12You can exchange them for goods, services, including services of material protection. The semantics of money is in fact self-reinforcing.13However, let us not forget that trade, distribution, and accounting may well be much older than money. The first manifestations of writing, from the eighth century BC, namely the token systems found by Schmandt-Besserat14, are dedicated to counting kept animals, and therefore probably to the ‘a(chǎn)ccounting’ of such animals, own or owed. We know that cattle can be used as trading equivalents, or ‘capital’15, as seen from the Roman distinctionpecuniaversusfamilia, “small cattle” versus “big cattle”, the latter not used for ordinary trade but for more radical investments. When money filters into the practices of exchange, maybe five millennia into the agricultural societies emerging after the end of the last glaciation,something radically new happens to social life and cultural activity: a huge growth of societies under unifying rulers, and the beginning of monotheism (such as early zoroastrianism).16Both may be causally related to the way social formations are slowly and gradually permeated on all levels by the same massively and intensely repeated symbolic references. The next version of the stratification graph shows the principle (fig. 4). We may therefore distinguish three forms of monetary capital: 1) the concrete exchange-based, organic and reproductive capital, 2) the investment-based productive capital, and 3) the speculation-based financial, or symbolic capital17.In a sense, the third, symbolic level of monetary practice is primordial, since money originates there, if I am right; so, in the same sense, financial capital is a primordial form of money.18But as early religious and law texts illustrate, it is immediately used for buying work force, services, goods, and of course food. On the organic level, it constitutes thereproductive capitalthat circulates between food markets and income from paid work or sold products; small communitary capital formations—created by the invention oftaxes—cover the necessary infrastructure, education initiatives (schools), health-improving initiatives etc. The finality of this basic circulation of money is evidently thereproduction of human lifein the framework of various sorts of households: the simple meaning of the termoiko-nomy,19which is further used as a (problematically inaccurate and misleading,hence ideological) metaphor for the political “economy” of entire societies.

Fig. 4. The three forms of monetary capital (in blue on the graph): reproductive, productive, and financial

On the technical level, theproductive capitaloffers a different form of monetary circulation, and a different set of semantic concepts. Here, money can be stocked in‘property’ and can be ‘invested’ in industrious or industrial processes of paid work whose products are sold on the market of goods, so that the circular effect of ‘making money’by organizing production and distribution based on proletarian20workers paid by the money just ‘made’, that is, the surplus value ingeniously described by Karl Marx, can createprofitto reinvest, to stock in property, or to place in ‘speculative’ enterprises on the higher, symbolic level. If a section of the population cannot access the technical level as proprietors, it becomes in fact a ‘proletariat’, and the part accessing and controlling the productive capital becomes historically the ‘bourgeoisie’, the class of classical capitalists.

Thespeculative capital,on the symbolic level, allows a non-working proprietor elite of a population to ‘invest’ in entire productive enterprises and to treat these as abstract ‘goods’ whose profits—typically becoming rents—are objects of conjecture and‘speculation’, that is, moving capital in and out of entire production zones, and countries.Speculative profits are obtained by investments in investments, and are used in many ethically more or less problematic ways, essentially for political manipulation, lobbying,buying rulers or propagandists and feeding secret agencies and mafias; for imperial,expansionist, colonial, energy-related or religious warfare; and for controlling illegal and secretive mega-markets exchanging reference values such as uranium, gold, drugs, art works, jewellery, etc. It is worthy of notice that the activities happening on the symbolic level of capital and power are considered as situated ‘a(chǎn)bove’ ordinary legality; sovereignty is allied with sacredness and is therefore essentially untouchable and not accessible to formal lawmaking and jurisdiction.21Laws mainly exist as immanent regulators of productive and reproductive life, on the second level of social structure. They presuppose a public sphere of discourse, whereas the symbolic transactions transgress this sphere of discourse; they are only displayed if the ‘show’ serves the imaginary construction of beliefs and support (the social dream factory, so to speak). Money buys lives and deaths, and modern ‘lobbying’ is a good model of the alliance of secrecy and display that dominates on this level. It is, in this sense, constitutively transgressive, which is no doubt the most important obstacle to all political or judicial attempts to limit its dangerous effects on societies, but it is no doubt also the most forceful motive for individual and pathological aspirations to power—meaning “total”, and totalitarian, unbridled power beyond moral restrictions. Power in this sense is psychologically sexy to the point of inducing psychopathy and psychosis: madness.22It can be strongly seductive if supported by submissive social communication, and it has demonstrated its appeal to ‘the People’throughout the various, more or less irrational, totalitarian populisms, or despotic populocracies, of world history.

The most important effect of the introduction of the systems of capital in a social formation is, however, the modern vertical integration of the instances (1), (3) and (5),community, property, and sovereignty, which finally become levels of institutional,hierarchical Nation States.23The Statewas basically and primordially just the reproductive community, but it is now also materialized in property as real estate, the ‘property of the people’, ‘res publica’, an independent, overarching social Subject that can own and manage productive capital. The holder of sovereignty becomes a ruler of this vertical(three-level) State apparatus, paid by generalized taxation and supported by both a currency-controlling ‘national bank’ and, often, a religious establishment.

The phenomenon of the integrative and ‘national’ State is thus inseparable from the monetarization of the social formation. The smooth trans-capitalistic (three-level)circulation of monetary values and the subsequent material exchanges are what gives rise to the protective (monetary, currency-based) feeling of social oneness we find in nationalisms,paradoxically running in parallel to the still more exacerbated contrasts between the forms of capital—the speculative, the productive, and the organic-reproductive—and the population’s class gaps, an inequality following from these contrasts. Money, State, and‘People’ are interdependent concepts. But markets currently integrate internationally, and financial operations do that particularly fast; markets and speculative movements expand the domination of money so intensely that it tends to dissolve the national, that is, Statebased, legal boundaries in favor of unstable networks of capital streams, a process now referred to by the termglobalization(French:mondialisation). The globalization of money means that nation states can all be indebted to non-national, globally active banking systems connecting the speculative capitals and sovereignties of the world. In this process,money seems to lose all reference to currencies and metals, and to become a purelyfiatentity that can be createdex nihiloby issuing debts, as Graeber (2011) suggests. Money seems to become radically infinite, since nothing limits its continuous creation and the subsequent creation of indebted instances. This historically important process is now reaching the limits of possible substantial growth of production, and its destructive effects on the planet make it clear that numerically infinite economies cannot harmonically coexist with a qualitatively finite and fragile planetary ecology.

The political consequences of this dilemma are not yet known, but international confusion is increasingly felt, and the human costs of the political unrest caused by the current frenetic behavior of capitalism are already unbearable.

What we call representative democracy is clearly an effect of the integrated State,where the hierarchical ordering of the levels of stasis can be expressed in terms of formalrepresentationof individuals and groups by other individuals and groups. Since the entire system is constitutively permeated by money, and representative status can be handled as a sort of commodity, the representative principle is, however, essentially unstable. Its monetary origin and ground remain manifest in its instability: mafias, lobbies, totalitarian excesses are never far away from the pockets of democratic ‘representatives’. In this framework, social life will thus contain a political life, which mainly regulates the relative strength of the statal institutions on all levels and the market interests on all levels, as these functions affect reproduction, production, and sovereignty.

Since political life unfolds in the substance of discourse, the statal side opposes the commercial side as a ‘left wing’ opposes a ‘right wing’ in the discursive public sphere, or as a ‘progressive’ versus a ‘reactionary’ attitude in discourse. We might call this standard variation thehorizontal dynamicsof political discourse. State supporters versus market supporters. There is, however, a different determination of discursive style to consider,namely the vertical dynamics stemming from the superimposed capital forms. The third,symbolic stream generates a ‘wild’, transgressive motive that conceptualizes social power in terms of charisma-baseddespotism, whether autocratic or theocratic, or both. This style contrasts with the conceptualization of social power emanating from the productive capital,which is and must belegalistic. Legislation, based on bureaucracy, is central in political life on the level of the productive capital.24Despotism and legalism form an essential vertical opposition, or variation in style, crossing the horizontal left–right opposition. So just as we find two forms of ‘left-wing’ discourse, one revolutionary (‘hard’ and more or less despotic) and the other reformist (‘soft’ and legalistic), we find in ‘right-wing’ discourse a split between ‘hard’, despotic reactionaries (populist, fascist) and ‘soft’ legalistic conservatives. However, on the basic level of reproductive capital, the discourse is rather of a third type, namelypragmatic. In the perspective of this discourse, on the one hand, even bad solutions are better than bad problems, so in some cases ‘hard’, terroristic anarchism,in other cases ‘softer’ and more democratic anarchism will be preferred, depending on the immediate effect of the remedy.25On the other hand, short-term pragmatism,opportunism, can contrast long-term pragmatism, grass-root ecology, seriously; short-term solutions to the problem of ‘getting rid of’ waste by dumping it in the oceans create longterm problems by eliminating aquatic animal life, an important source of human food.Ecology in the sense of this essay is in fact a form of long-term pragmatism, namely what economists call ‘negative externalities’—the fundamental problem being how to maintain the planet as a human habitat. Capitals, that is, the agents of capitals on all levels, are not inherently organic and not naturally interested in questions of life; money is not a biological species, just a predominant form of human symbolization regulating life and, in the current historical situation, more than ever deregulating it.

3. Problems

3.1 The ecological problem

In the integrated and globalizing capitalistic perspective, coherence can only exist in terms of monetary coherence, which means that the semantics of money must prevail.Themeaning of moneyis to circulate—protectively26—and in order to do so, since circulation however smooth is costly and implies loss, to increase, instead of decrease:growthmust happen. An ideology of necessary growth must develop. But for material growth to happen, the negentropic-entropic loops exploiting natural resources on all levels (organic, technical, symbolic; affecting soils, oceans, atmosphere etc.) must be exploited infinitely, that is, must be handled according to the formal infinity of capitals; and this has led to such destruction, pollution, and exhaustion of habitats and resources that human and animal life on the planet is now becoming seriously threatened. The metaphorical use of the organic termgrowthfor the inanimate, purely symbolic finality of capitals is tragically ironic. Money is not a living organism that can “grow”, as this metaphor has it. The problem is whether it will manage to fully exhaust and destroy its own necessary material foundation, the natural loops that carry it, before it is itself ‘outgrown’ by a healthier principle of human organization, a sustainable form of reproduction, production,and symbolization. We may have to discuss the possibility of ‘sustainable symbolization’and thus, of the sustainability of money as such. What is bound to happen globally is a dramatic matter of time, as ecology always is and locally has been. Can money be separated from capitalism and be cured from its apparently inherent madness? Can some humanethicsfinally make money rational and ecologically viable? Or can human civilization, as we know it, exist without the symbolic medium we call money? The latter question evidently presupposes an understanding of what moneyis, which is the question that motivates our semiotic inquiry.

3.2 The political problem

If the “growth” of the generalized and globalized capital is slowed down by the ecological difficulties it has created, and in particular by the impossibility of obtaining the quantities of energy needed for increasing the material production, then an increasing part of the total capital will move ‘upwards’ toward the pure symbolic and speculative level. This is happening now and may account for the current ‘growth’ of diffuse and irrational outbursts of sovereign insanity, including neocolonial warfare, religious militancy, and,no doubt, a very dangerous general turn to religiousandneocolonial belligerence, in many parts of the planet—again, capital must stay active, circulate, flow, move and be used in order to exist. It exists ‘growingly’, andsymbolic hyperactivityof this kind can probably only be stopped by political intervention. But such intervention would mainly or only spring from the basic, pragmatic level, where populations are hit by corresponding misery; and here, the weakened monetary flow reduces them to just asking again for... protection, i.e. more money and insanity. Intellectual political resistance is additionally inhibited by the lack of conceptual distinctions between capital forms, and by the predominant vision oftheCapital,das Kapital, as one tremendous, homogeneous,indivisible, and maybe invincible block, not a stratified system whose strata might be made relatively independent and amenable to regulation. The semio-ecological view may therefore become useful.27

3.3 The problem of knowledge

Institutions for the development and the transmission of knowledge are collective Subjects or persons that are in the hands of either the State or the Market, and often in both sorts of hands. These share the fate of the ‘public sphere’ of information, debate, critical discourse, entertainment, advertisement, and propaganda – namely to be a plaything between States and an integrated, overarching Market. Human minds naturally strive for insights and accurate knowledge of the world, and at least what we callscience, history,and philosophy, three main branches of real systematic and critical search for knowledge,are essentially the developed collaborative versions of this natural human drive.However, knowledge and its ‘truths’—however approximate—can be disturbing, and morally challenged persons can be persuaded monetarily to hide, deny, and distort such disturbance. As organic, technical, and symbolic knowledge is becoming increasingly important to the survival of human beings in the current dangerous physical and organic state of the planet, these counter-epistemic inhibiting factors are becoming particularly problematic. Thetechnologies of epistemic and counter-epistemic agency, the industries of information and delusion, including the media of the ‘public sphere’ and of the new‘private sphere’ of more intimate personal digital media, make the task of politically building on real knowledge, rather than on interested misinformation, extremely difficult. As Plato already observed, truth should not be a commodity that you can buy (as you can buy and take a course in rhetoric with Gorgias). Neither truths nor money are ordinary commodities; they are ‘sovereign’ symbolic entities. But money can therefore oppose truth, and knowledge is often ‘taken hostage’, ‘bought’: privatized, patented as property,made inaccessible and useless. However, truths are the necessary weapons of an ethical regulation of money-based power, because truth is a supreme form of authority that power must itself appear to possess. Why else would it have a tendency to lie?

3.4 The problem of culture

The frequently occurring direct fusion of sovereignty (5) and religion (6) in a conjuncture of inflated financial-speculative capitalism creates a particularly dangerous and explosive situation in a technically fragilized world-system of societies.28Religions merging with sovereignty potentially create a dangerous caste of priest-warrior-bankers-rulers on top of weakened political States. In such conjunctures, ethnic passions will replace rationality and inhibit, censure or exclude deliberative discourse, and the local and global results will be utterly destructive. By contrast, when ethno-cultural particularities are maintained and only transmitted on the basic organic level of households, their pretentions are limited, and they mainly assure elementary reproductive functions in family lives:ritualized burials, marriages, baptisms, celebration of events in the mythical calendar.However, these cultural functions ofcult(in the instances 1 and 2 of fig. 3, above) are easily subsumed by the religious-financial elites (6), which can then mobilize the organic masses, already distressed and disoriented by the destructive effects of speculative capitals, and manipulate these to follow irrational orders and interests of inflated religious rulers (5-6).

4. (Im)possible Alternatives

Contemporary philosophers frequently argue against the current structural reign of money,which now causes these spectacular disasters; but most often they argue without indicating realistic means of changing the situation. Certain forms of hope are indeed expressed. So, economists hope that more and new, hitherto unseen forms of ‘growth’ will eventually ease the situation and repair the damage caused by capital-driven violence and destruction.Such expectations of course do not include the devastation of nature; for economy is not ecology. On the other hand, revolutionary mysticisms thrive, among mundane philosophers and intellectuals hoping that the global proletariat will somehow again climb the mythical barricades; and yet the elementary question remains: what to do about the monetary or otherwise symbolic condition, even after a new revolution, global or local. The question concerns all inhabitable areas of the planet—will mankind be able to reorganize and develop a high-technological global social formation without its ‘wild’ speculative money? Or would we have to scale down to tribal society formats and try to make that work? Or again:can money stay with us but without capitalism? This sounds like a rhetorical question. But it may become a realistic and even an urgent problem to solve.

Certain anti-capitalistic views would see the solution in a new strengthening of the State, making it possible to fight the strong integration and hegemony of the markets. But as we are seeing already, States and markets can be strengthened at the same time; we could reanimate or generalize one of history’s particularly unfortunate anti-capitalistic models, but global ecology is not likely to be served.

Neo-liberal thinkers are convinced that new technologies of some kind will overcome the hurdles of growth; they hope that increases of energy consumption will therefore not be necessary. Production is supposed to grow but the energy flow will proportionally shrink or stay on current levels. The new technology will not need increased extraction, just immaterial smartness. But smartness alone is not relevant production in any sense before it producesmorethan is presently the case, which again requires increased extraction and energy and material consumption, and if growth is just stagnation with lowered costs due to smart robots, the production and maintenance of these new machines will again require increased extraction and consumption. A growth with zero-increase in energy consumption and waste is simply impossible. Believing otherwise amounts to relying on miracles.

Money has created the human historical world as we know it. And money is now about to destroy it. Still nothing is in view that could replace it without itself being money(e.g. bitcoin29). The remaining question is therefore the deepest and simplest: Can money be changed into something less pervasive and destructive?30Or is there another semiotic way to organize an intelligent post-capitalistic society?

The answer may depend on the interpretation of the underlying flows and the social stases that these flows must create for human populations to live.31Maybe new attention should be paid to the sacred origin of money32as an atavistic means of contact with the divine. It should be clear that reducing the capitalistic size and importance of this instance((6) in the model) and its alliances with political rulers ((5) in the model) could reduce the toxic effects, initiatives, and attitudes that flow from this sphere and that inhibit human political thinking: intolerance, arrogance, fanaticism—irrationalisms of all kinds.No viable solution can be worked out under the dominance of violence, corruption,and financially militarized religion. If the symbolic flow of financio-religio-despoticospeculative capital can be reduced and weakened,state rulers may gain rationality,which is a prerequisite for gaining control of the lawless forces at work on this third level. The goal would be a significant reduction of the role of ‘wild money’ in the global circulation, that is, a certain ‘de-capitalization’ of the third level, and a corresponding ‘rerationalization’ of governance.

Instead of yielding to despair faced with the global capitalization of money, it may be possible to dwell on its substantial layering, which subsists despite all types of State and Market integration, combination, and conflict. It may be important to remember that the role of money is stilldifferentfrom one ecological level to another, and that the danger to mankind of activity being determined mainly by monetary flows increases drastically from level to level upwards, and decreases in the opposite direction. Money needs to be taken ‘down’ from speculative dominance. The fatal lack of rationality occurs mainly at the highest level; therefore, initiatives to limit the severe ecological and human damages caused by the functions of capital in our contemporary societies should primarily target the symbolic top of the monetary flows and their influential bodies of power, the ties between speculative wealth, politico-economic ruling power and religious mind control.The theme of growth may be crucial here: it needs to be deeply problematized.

Since the Axial Age, through Antiquity, the feudal Middle Ages, the commercial Renaissance, the agonistic Baroque, Industrial Romanticism, and technological Modernism, money has given rise to many great and impressive social and cultural developments and achievements worldwide, however often obtained to a saddening price paid by nature and life. Currently, the planetary situation calls for a profound rational reconsideration of the monetary world order, and we must find ways to empower forms of political rationality capable of changing the perspective, and in particular, to reduce the irrational agency caused by the monetary world orderas it is.

If I am right, the symbolic flow, which is the main historical cause of the disaster,has an interesting weak spot, namely that it is and remains—symbolic. It is semiotically symbolic and refers to itself; this is the root of all irrationalism, but also of rationalism:‘meta-language’, self-reference. Symbolicity is necessarily driven bylanguage, which is easily used self-referentially. And money has often been compared to language.33It is strikingly true that language, in the shape ofdiscourse—in fact a rich display of differentdiscourses, political, religious, ideological, etc., each with its own aesthetical norms of well-formedness and rhetorical forms, which constitute the delight of semiotic analysis34—pervades social and cultural formations as much as, and even more than money. Money itself would not exist without language to negotiate, define, and compare the properties of pieces or quantities of monetary value. But furthermore, religious practices as well as political acts are entirely shaped by language—their operations and terms depend on the intelligibility and thecredibilityof political and religious discourse, and of their combinations. That is why social rulers and religious authorities must spectacularlydisplaytheir agency in constant massive and, of course, ostentatiously costly, lavish and wasteful theatrical setups. If an equally massive or socially audible rational critique of these displays, and their inherently vacuous futility and essentially stultifying simulacra,could obtain sufficient material support to become a real challenge, despite all technical attempts to silence it, then therolesof money may in fact be changed, and the fate of mankind made to look less sombre.

An explicit critique of transgressive sovereignty—what sort of discourse could materialize its task?Wherewould it speak from, as Michel Foucault (1971) would ask. While symbolic capital and activities in general are inherently aggressive and transgressive, the authority of the law is inoperative on this transcendent level, often technically powerless, as demonstrated every day in contemporary social and political life. Still, language has an advantage, and even sacred versions of sovereignty have a weak spot where this advantage is located: language and only language can make it exist socially, and language comes with a built-inethics of enunciation: to speak is to care for others, to give voice to an elementary ethical claim of respect for life and therefore for truth. Evil is inherently silent or nonsensical. Anethical critique of sovereignty,formulated in the prosaic or poetical language of organic human experience and subsequently in the discourse of a philosophy of responsibility, may be a means to obtain the necessary change of mind. All humans capable of following a story and grasping its narrative logic in principle do understand the distinction between serving life and serving death, between helping and harming, and between responsible reason and irresponsible madness. The semantics of a fundamentally ethical claim in fact should have a chance to at least transcend ethnic passions and powerful pathological behaviors. Lawyers of the current academic sort will probably reject it, but beyond the unavoidable formalisms of laws, there is anethical conditionfor human life to make sense, namely the call toprotect the other, not as money was supposed to do according to its semantic ‘value’, justprotect yourself. This grounding ethical call to protect others around you (the individual you),including those of the still more precarious future, is a strong call deeply rooted in human nature, and it is, I think, strong enough to fight and defeat the speculative madness of money, when the ecological catastrophes accumulate.35As idle capitals accumulate, so do these catastrophes, by direct proportionality—and there will be a tipping point where the discourse of ethical ecology becomes the only voice capable of countering radical pessimism. It would however be cynical to passively await such a moment.

The monetary sign is performative, that is, it has the same performative force as the utterance of a declaration, a promise, a threat. It is a materialized promise. Either the money is given by A to B or not; either the promise by A addressing B is made or not. If given, made, a situation has changed. But money can only be given and received within a frame of specified exchange that must be defined by language. This exchange is an act of ‘buying’, of ‘lending’, of ‘donating’, or of ‘bribing’, etc. Language is therefore conceptually superimposed on money. This is interesting, because in the last instance,and especially when used for illicit, transgressive purposes, as shown in crime fiction and corresponding reality, language must follow an inherent principle ofdiscursive ethicsthat forces the user todo as promised(in casu, keep a secret, tell the same lie as someone else, etc.), that is, to be linguistically reliable. If this principle is not respected, the subject is excluded even from a criminal community. Only psychosis or brain damage can make the speaker deviate from this fundamental principle of ethics of language use. Ethics in this sense is stronger than morality and law, and therefore it can bewhere to speak fromin a future critique of destructive capitals. Laws can be bent, ignored, interpreted in many fanciful ways; but the ethics of language use, which is the grounding ethics of the human being as such, cannot. This source, the grounding human ethics of meaning and truth, is from where art, literature, music come, and from where responsible scholars, scientists, and philosophers speak and write, if they have the personal capacity and integrity to assume their task, which admittedly is not always the case. In particular, one may quite often suspect academic economists to neglect to display such conceptual and ethical integrity.

Money may be pervasive, but it is ruled by language. It may therefore be politically and structurally changeable by language, art, music, emotional expressions of commitments to life, in the name of the very ethics that makes us human. We may have to find our wayintothis critical core of our communicative being if we want to find our wayoutof the current maze of despotic or erratic capitalism, mental confusion and ecological disaster.

5. The Realms of Meaning

In Georges Bataille’s so-called heterology, which describes experiences and observations of behaviors corresponding to what is happening on the symbolic level in my analysis of societal structure, power and madness are linked to excess, transgression of rationality and of norms, behaviors of ‘sovereignty’ both in a collective and in the individual scale.His social phenomenology is indifferent to such scale shifts between the macro-social and the micro-social or even intimate realms. It strikes me that this conceptual plasticity calls for justification, and that we might now have an explanatory argument at hand.

The three levels of societal organization, including their interactions and interdependent processes, with or without the intervention of money, are matched by three levels of semantic organization that we find inall human semiotic phenomena of meaning-making:in language, art, music, affectivity, normativity. We will briefly consider this subjective perspective and its consequences.

5.1 Levels of meaning in socio-cultural life

The terminology proposed by psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan36to characterize the main instances active in the human mind:the Symbolic, the Imaginary, the Real, can be transposed to describe the levels of meaning in socio-cultural life:

III. TheSymboliclevel of meaning: authority and ritual force; ‘identity’ and violence;POWER.

II. TheImaginarylevel of meaning: social representations and projects of all kinds; WORK.

I. TheReallevel of meaning: family, friendship, love, births, deaths. Existential aspects; LIFE.

We experience social life first by growing up in a collective setting, by being and taking part in its daily endeavors. Our existentialrealityconsists of passionate bindings to others and learning to follow their rules and norms, their ‘moral’ principles. But we soon learn that there are larger social horizons regulated by laws issued by institutions and addressing us as citizens, as principles of ‘legality’ to follow (or fight). We encounter this sort of meaning as an encyclopedic mass ofimaginaryentities: projects, political ‘dreams’and ideologies, references to knowledge, myths, stories, information, propaganda, etc.Finally, we discover that there are ‘higher’ orders of decision making, transcendent principles of authority, sacredness, andsymbolicacts without rational explanations, which seems to venerate some sort of shared destiny that calls upon our participation. The latter‘order’ is no longer regulated by the civil and ordinarylaw, nor by themoralnorms of the basic, real level, but either by the sovereign madness of sacralized rulers or else by some superordinate principles of universalethics—such as what we call the Human Rights and an ethics of care for nature: ecology.

5.2 Language and subjectivity

A division in the registers of meaning characteristic of language is straight forward and appears natural. In the register of speech acts, the presupposed authority of the speaker and the relevance of the hearer makes it possible to create new interpersonal and social situations by declaring, promising, imperatives, curses, conjurations, oaths, and other performative utterances in the present tense. This is the symbolic semantics of language.But in the framework of the non-performative functions of language, communication simultaneously builds universes ofimaginarypolitical, educational, esthetic, narrative meaning allowing human societies to operate as huge networks of connected and collaborative (incl. polemically responsive) minds. The open-class words that constantly change their meaning and reference, migrate between languages, and follow the historical and technical developments of cultures and countries, form the necessary grounds of all social life. Finally, the phenomenological,realregister in language is dominated by proper names, place names, pet names, nicknames, markers of singular (numerical) identities that are essential in our affective and intimate life; idiomatisms, dialects, sociolects, and sexolects may therefore pertain to the same register.

In the domain of the personal pronouns,you (singular) and Iare anchored in the basic, real, phenomenological register, whereaswe and you (plural)mark the collective imaginary, and thewe (singular),as in “we, the king”, refers to the symbolic instance.

In these respects, language is shaped by deep ecological structuration of human sociality. It can be argued thatsignsin general, not only linguistic signs, but visual,auditive, gestural, or otherwise humanly configured expressions, including artistic expression, which are often complex integrations of expressions of various modalities, manifest a similarly differentiated semantic unfolding. One part of a sign always signifies an instruction: thesymbolicaspect; another part always to some extent indicates what something referred to is like: theiconicaspect; and one part of the sign connotes its context or origin and value to the speaker, therealaspect, in Lacan’s sense.

One of the most important categories of subjectivity is of course affect. Human affectivity divides in several independent but interrelated systems, including regulators of our mental and bodily state in different time scales. The ‘fastest’ affects are the shiftingemotionsby which we experience our constantly changing social situations: joy, surprise, anger, fear, sadness, concern, sorrow, shame, pride, contempt, disgust... The time scale refers to minutes of expression and feeling. This category corresponds directly to our insertion in the socialimaginary.

The category of what we callmoodscover the somewhat ‘slower’ affective states of excitement, elation, ecstacy, and their opposites: depression, dejection, melancholy. Between these polar extremes, there is a neutral state; the time scale for being in the nonneutral states of mood is the day, because they are regulated by our circadian rhythms,and because thesymbolic calendarand our ritual behavioral routines let our binding to the symbolic instances determine the choice of state, at least to a certain extent. Religion is therefore a regulator of mood, and one that easily binds our subjectivity to sacredness and authority.

Finally, the sort of affect we call passions relates to our existential feelings: being-inlove, love (itself), grief, affection, bitterness, resentment, hatred... Those states of mind and body are ‘long-term’ affects. Their scale is the year; they regulate and often dramatize our real existential life.

5.3 The architecture of the human mind is identical to that of society. Madness

It is thus a reasonable assumption that the three levels of social flow are imprinted in the human minds and bodies, that is, that they have been shaping our subjectivity during the many—maybe at least ten—millenia in which we have been living in social formations articulated in this way. This would explain that social events immediately affect us individually; from gossip to news programs and media messages, what ‘happens’around us directly determine our personal thoughts and feelings to a striking degree:the individual experiences society as a part of itself. So social ‘crises’ often become individual crises as well. And madness in one sense becomes madness in another sense:social rulers experience their body as a country; psychotic conditions can induce similar feelings, for example the feeling of being a ruler because the body has become a country. Psychology and sociology coincide as to their orders, levels, and semiotic processes—the human mind is a radically social machine, one may say.

If this is correct, at least as a first approximation, we may begin to understand how money can enter the human mind with such a tremendous imperative force, as the semiotic entity that the individual feels it must relate to. Money can enter the mind exactly as language does and by following the very example of language (given that language must have preceded it in the human symbolic evolution). Money becomes an irresistiblemaster signin the flows of our affectivity, and quasi-automatically regulates our reasoning, giving rise to the so-calledeconomical rationalitythat critical theories have problematized. However, we do not need any theory of authoritarian personalities in order to grasp the endemic logic of monetary submission in modern human psychology.We do not even need theories of ‘reflection’ by which the mind mirrors social processes;our mindsarethese processes. What we instead do need in order to fight and limit the madness of money in our real, political, and symbolic lives is an understanding of the genealogy and general semiotic economy of money and the underlying ecology. In the finiteness of our ecology is the remedy for the delirious infinity of our economical imagination.

Villeneuve-sur-Yonne, June 2017

Notes

1 Walt Disney’s, that is, Carl Barks’, philosophical and pedagogical masterpiece, the cartoon Donald Duck, has a character, Scrooge McDuck, who owns a money tank filled with gold coins; it serves as his swimming pool and allows him to physically enjoy his immense wealth by bodily contact with the liquid of his ‘money’.

2 To ‘give someone your word’, in the sense of making a promise, has the same effect of irreversibly depositing an entity of value. You ‘pawn’ your language and must ‘pay’ (fulfil the promise) to get it back.

3 Critical semiotic approaches are taken by social philosophers such as Jean Baudrillard (1972)or Ferruccio Rossi-Landi (1974). The assumption of these attempts is that linguistic and monetary signs essentially work the same way. Words are the money of our bodies. Both are conventional, and both have performative force. We will return to this analogistic view, which calls for serious modification, a modification that can profit from a closer study of monetary functions.

I should specify that I am talking about standard neoclassical economics. I admit that several heterodox economists, and the school called Modern Money Theory (MMT), or Chartalism, do place monetary institutions at the center of macroeconomics. A main distinction is made between metal money and paper money, the latter seen as being created by states through declarative acts (therefore nicely called:fiatmoney). The first modern theoretist of money, Ferdinando Galliani, whoseDella moneta, inspired by Hume, appeared in 1751, was a‘state metallist’: he suggested that metal money emerged spontaneously out of states’ need for a manageable tax-paying reference.

4 Georges Bataille (1944). The negentropic loop referred to here also underlies Bataille’s (1947)concept of a ‘general economy’, which opposes the restricted economy of production, profit,and reinvestment, by including the instances of destruction of wealth, as in wars or costly displays, typically related to the symbolization of sovereignty.

5 I will argue that money arises from symbolic activity in this sense. The contemporary ‘Modern Money Theory’ economist L. Randall Wray, a student of the fiat-money pioneer Hyman Minsky, supports the view that all these psychological and symbolic aspects of collective life are involved in capital formation (Wray, 1990). He opposes the standard and Marxian view that money emerges from exchange of goods. Whereas the exchange-based view imagines that money as such develops bottom-up, so to speak, i.e. from barter, he reaches a conclusion similar to that of the present author, namely that it originates in a top-down process, from the symbolic level.

6 This statement sounds like an ideological standard phrase. But understanding the origin of‘private’ (person-assigned) property is not a problem solved by Morgan, Marx, Engels or any other modern social scientist. Here, we will bluntly assume that the concept of real property evolves out of ownership applied to objects and entities on the level of the technical flow. How‘private’ it eventually becomes, or again ceases to be, is a historical question. Friedrich Engels’(1884 – 1892) work on the subject,The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State,remains a major contribution to the discussion.

7 In ancient cultures, temples often also served as banks. The biblical Jesus caused scandal by expelling the bankers from the temple of Jerusalem, thus marking the modern distinction—which remains relative. The original unity is recalled by institutions like the most CatholicBanco del Santo Spirito.

8 For there to be a population, there has to be a territory inhabited by people sharing language,moral and technical habits, history, and interpreting that territory in terms of its life forms.

9 Graeber, 2011. The original German term isAchsenzeit, the period from about 8th to 3rd century BC, suggested by the philosopher Karl Jaspers (1949) to be a decisive founding phase of the great civilizations that would follow in many areas of the planet simultaneously.In Mesopotamia, gold ornaments first appeared in the fifth millenium BC. Gold played a prominent part in funeral gifts and ceremonial objects. Cult statues was often covered with gold foil. In the mid-second millenium, gold from Egypt was imported in exchange from the pharaoh by the Babylonian kings in exchange for richly worked textiles, war chariots, etc.

10 Brandt, 2015a, 2015b.

11 Remember that, e.g., the etymologically important JunoMonetawas a powerful protective Roman goddess. The imputed inherent protective force of money therefore grounds its semantics of abstract ‘value’.

12 Money thus also exists as a store of value. In contrast toSay’s law,as J. M. Keynes critically named this well-known belief that money is just a momentary link between two acts of buying,and that the market is thus self-regulating, we in fact hoard money as a bulwark against uncertainty. Jean-Baptiste Say formulated the principle in hisTraité d’Economie politique,1803. “Money performs but a momentary function in this double exchange; and when the transaction is finally closed, it will always be found, that one kind of commodity has been exchanged for another.”

13 Of course, the affective background of the semantics of money, on this account, is the omnipresence of the universal basic emotionfear. Money is experienced as a remedy against this feeling. Through the three millennia of the history of money, this circumstance has stayed stable. Money is still experienced as protective. This is true even when it is used as female adornment, for example. Or in wedding rings, protecting the contract. And it is characteristic of sacred imagery to still use precious metal adornment abundantly, as if to constantly remind us of its origin.

14 Schmandt-Besserat, 1996.

15 The wordcapitalis derived from the same Latin root as cattle:caput, “head” (of cattle).

16 Religion and sovereign money seem to cooperate across cultures and through history. On the websiteNew Economic Perspectives, L. Randall Wray critically quotes Nobel Prize winner Paul Samuelson’s remark, that “[...] one of the functions of old fashionedreligionwas to scare people by sometimes what might be regarded as myths into behaving in a way that the longruncivilized liferequires. We have taken away a belief in the intrinsic necessity of balancing the budget if not in every year, [then] in every short period of time. [...]” Wray does not believe in the religion of balancing state budgets for the mythical reason that ‘one must always pay what one owes’. He writes: “We don’t need myths. We need more democracy, more understanding, and more transparency. We do need to constrain our leaders—but not through dysfunctional superstitions.”

17 Hyman Minsky, one of the founders of MMT, distinguished three forms: commercial, welfare state, and money manager capitalism, fairly comparable to our three strata of capitalin general. Minsky (1986) noticed that a surplus of productive capitalimmediatelyspills over into speculative capital, which destabilizes the ‘system’.

18 Commodity money (coins) was first replaced by representative money (paper) in China,according to Marco Polo, and became then “represented” by bank notes in the 17th century in Europe. Paper money remains anchored in references to gold or silver until the second part of the 20th century, when the references seem to become autonomous: the pieces of paper finally inherit the protective magic of the metals, if properly authenticated. Paper money consists in documents stating debts to the person owning the documents. The debt statement is a performative act, adeclaration of a promise, signed by the issuer of the unique and singular piece of paper to whoever will own it.

Commodity money represents value as a link between nominal units of currency and quantity of coined metal. A very interesting debate involving the philosopher John Locke took place in the last decade of the English 18th century, around the Great Recoinage 1696-1700;guided by the philosopher, the run-down shilling was recoined with as much silver as there had been a century before, and it was decided to keep the rate fixed. Soon, the pound was bound to fixed amounts of gold in the same way, by the Bank of England. See John Locke, “Further Considerations Concerning Raising the Value of Money”, in Kelly, 1991.

19 Theoikosis of course a house, a home, but it does not yet really count as a value, contrarily to what is the case on the technical level, where it becomes a priced Property. Mostly, either the dwelling is built by the owner or it is rented. On the other hand, the termecology—introduced by the German biologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel in 1866—refers to the sameoikos,now in the sense of “niche”, and tologosin the sense of study: the biological or social study of the interactions between organisms and their environments.

20 Banks define the difference between capitalists and proletarians: the former can borrow money, because the can offer mortgage, the latter cannot, since their ‘property’ is considered null.

21 That sovereign governments can create money ‘out of thin air’ still scares modern citizens.

22 Sergio Tonkonoff (2012) offers a fine and finely written account of Bataille’s view of human transgression. Sovereignty in this dramatic sense can be seen as a paradoxically permanent ‘state of emergency’, as in the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s thinking, inspired by Carl Schmitt. See Agamben 1995. He understandably wishes to get rid of it altogether; I doubt the possibility of building a society without a symbolic level. But since thelawthat regulates the conflicts on the second level does not have much effect on the third level, we might instead look at transcendent principles such as the Human Rights to find the ethical principles that can limit the irrationality of this third, dangerously destructive level of sociality.

23 This conception is not far from the Chartalist view of the multiple functions of money (see

note 3).

24 We rediscover in this context Karl Jaspers’ friend Max Weber’s (1905) famous opposition of charismatic and bureaucratic power, both superseding the power of traditions and conventions,which are of course rooted in the necessities of reproductive life. In my view, Weber’s categories are essentially superimposed on each other, rather than historically sequenced.

25 We could call this style of management acowboy logic. The hero of such conflicts and stories is typically a pragmatician, which can be felt as a relief from the stressing higher-order conflict between the four predominant styles described here.

26 The meaning of money is to yield protection, if my analysis is correct. The fundamental concept of ‘value’ in economics is based on this semantic effect. Some heterodox economists, from Keynes and Minsky to Wray, may agree, whereas neo-classical mainstream economists just consider money as a neutral, insignificant element of macroeconomics.

27 There is certainly a dynamic Agonist-Antagonist relation between productive and speculative instances, and wild speculation stemming from stases 3 and 4 profits can be ruled in and stabilized by stasis 5. There is a feedback loop from stasis 5 to stasis 1: ‘financial reason’, in a sense.

28 I insist that there is nothing new in this alliance between sovereignty and religion. Its basic expression is the very existence of money, created at least 3,000 years ago. Still, stasis 5 and 6 can be kept distinct, as in ‘secular’ regimes. Ethno-religious passions frequently disturb this distinctive condition.

29 My colleague Todd Oakley comments that bitcoin is not money, unless you can pay taxes with it. An open theoretical question; I think he is right, in the sense that to be money is to be able to connect the levels of capital in integrated flows.

30 My reviewer, who evidently is a heterodox economist, comments nicely on the question: “It depends on the institutions around it. The power of sovereign currency systems to fulfill a public purpose that stabilizes societies is indeed possible, at least for a time, but pathological fears of insolvency (not possible for sovereign currencies) and inflation (not on the horizon) is a great hurdle to overcome. It also means embracing the transgressive prerogatives of the state(which can be used to fulfill the public purpose just as much as to aggrandize the sovereign).”

31 Modern Monetary Theory takes the view that the Sovereign or Government sector must run deficits most if not all of the time, as public debt in a sovereign currency is not only a debt in the nominal sense; more importantly, it is mostly savings of the private sector).

32 Weber already pointed out the close connection between economy and religion, but in a different key, namely as a relation between moral standards of Protestantism, especially Calvinism, and the norms of industrial capitalism.

33 See Rossi-Landi, 1975; Baudrillard, 1972 ; Bataille, 1949. The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure famously says ([1915] 1962), in Chapter IV of hisCours de linguistique générale,where he discusses what he callsvalueas opposed tosignification, in language : “To determine what a five-franc piece is worth one must therefore know: (1) that it can be exchanged for a fixed quantity of a different thing, e.g. bread; and (2) that it can be compared with a similar value of the same system, e.g. a one-franc piece, or with coins of another system (a dollar,etc.). In the same way, a word can be exchanged for something dissimilar, an idea; besides, it can be compared with something of the same nature, another word. Its value is therefore not fixed so long as one simply states that it can be ‘exchanged’ for a given concept, i.e. that it has this or that signification: one must also compare it with similar values, with other words that stand in opposition to it. Its content is really fixed only by the concurrence of everything that exists outside it. Being part of a system, it is endowed not only with a signification but also and especially with a value, and this is something quite different.” (Translation by Wade Baskin, Internet Archive). The question is whether signification and value can be separated totally. In the case of money, the quantitative value of coins is dependent on their being carriers of protective force; in the case of words, their interdependent ‘value’ depends on their significance as carriers of meaning that can support the communication of truths. If the ‘true’understanding of things protect us from dangers, we have here an analogous function of money and language in terms of signification.

34 Fontanille, 1998.

35 As the French ecologist Nicolas Hulot writes on the web page of his association: “In 2050, two hundred fifty millions of people will be forced to leave their habitat by extreme meteorological events (cyclones, typhoons, floods…). The rising waters may swallow between ten thousand and twenty thousand islands, many of them inhabited. One out of six animal species may definitively disappear…”.

36 See Jacques Lacan (1966, 1975), and passim. Lacan proposed to see the three orders as intertwined as by a borromean knot of three rings, each of which hold together the two others.Lacan is a difficult read, compared to Freud, but his three orders, developed in the discussion around the structuralist turn of psychoanalysis and the humanities in the sixties, may be one of his lasting contributions to social psychology.

Agamben, G. (1995).Homo sacer. Il poetere sovrano e la nuda vita. Torino: Einaudi.

Bataille, G. (1944).Le coupable(In?uvres Complètes, Vol. 5). Paris: Gallimard.

Bataille, G. (1949).La part maudite(In?uvres Complètes, Vol. 7). Paris: Gallimard.

Baudrillard, J. (1972).Pour une critique de l’économie politique du signe. Paris: Gallimard.

Brandt, P. A. (2015a). La construction sémio-cognitive de la valeur économique. In A. Biglari(Ed.),Valeurs. Aux fondements de la sémiotique(pp. 481-493). Paris: L’Harmattan.

Brandt, P. A. (2015b). On the origin and ontology of money. A brief note. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276970689_On_the_Origin_and_Ontology_of_Money_A_brief_Note

Fontanille, J. (1998).Sémiotique du discours. Limoges: Presses Universitaires de Limoges.

Foucault, M. (1971).L’ordre du discours. Le?on inaugurale au Collège de France prononcée le 2 décembre 1970. Paris: Gallimard.

Graeber, D. (2011).Debt: The first 5,000 years. New York: Melville House.

Jaspers, K. (1949).Vom Ursprung und Ziel derGeschichte [The origin and goal of History]. München:Piper.

Kelly, P. H. (Ed.). (1991).Locke on money. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Keynes, J. M. (1919).The economic consequences of the peace. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Howe.

Lacan, J. (1966).écrits. Paris: éditions du Seuil.

Lacan, J. (1975).Encore(1972-1973). Livre XX du Séminaire(Texte établi par Jacques-Alain Miller). Paris: éditions du Seuil.

Minsky, H. (1986).Stabilizing an unstable economy.New Haven: Yale University Press.

Monsaingeon, B. (2017).Homo detritus. Critique de la société du déchet.Paris: Le Seuil.

Rossi-Landi, F. (1975).Linguistics and economics. The Hague: Mouton.

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (1996).How writing came about.Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Saussure, F. de. (1962).Cours de linguistique générale(5th ed.). Paris: Payot.

Tonkonoff, S. (2012). Homo Violens. El Criminal Monstruoso según Georges Bataille.Gramma,13(49.1), 145-152.

Weber, M. ([1905] 2016).Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus.Berlin:Holzinger.

Wray, L. R. (1990).Money and credit in capitalist economies: The endogenous money approach.Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

About the author

Per Aage Brandt (pab18@me.com) is Adjunct Professor at the Department of Cognitive Science of Case Western Reserve University, USA. He studied with Greimas in Paris(Sorbonne Thesis 1987) and was the founder of the Center for Semiotics (1993) at the University of Aarhus, Denmark, and of the JournalCognitive Semiotics(2007). He was a Fellow of the Centre for Advanced Study of the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford, CA.And he is also a poet and a musician.

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年3期

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年3期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Stasis Salience and the Enthymemic Thesis1

- A Socio-Semiotic Perspective on Boko Haram Terrorism in Northern Nigeria

- Contemporary Discriminatory Linguistic Expressions Against the Female Gender in the Igbo Language

- Facebook Engagement and Its Relation to Visuals,With a Focus on Brand Culture

- Wilhelm II’s ‘Hun Speech’ and Its Alleged Resemiotization During World War I

- A Century in Retrospect: Several Theoretical Problems of Russian Formalism From a Paradigm Perspective