Teaching Syntactic Relations: A Cognitive Semiotic Perspective

Ghsoon Reda

Yanbu University College, Saudi Arabia

Teaching Syntactic Relations: A Cognitive Semiotic Perspective

Ghsoon Reda

Yanbu University College, Saudi Arabia

This paper suggests a theoretical model for teaching syntactic relations to foreign students of English Linguistics using insights from Cognitive Grammar as developed in Langacker (e.g. 1987, 1991, 1999) and elaborated on in Radden and Dirven (2007). The model deals with syntactic relations as participants in a prototypically structured network of events, radiating out from the experientialaction chain schema(a skeletal concept of force dynamics involved in the interaction between entities) (see Langacker, 1999). This involves dealing with syntactic relations as meaning-making tools that collaborate with the verb in a regular manner manipulating the prototypical schema. The aim is to draw attention to the need to add a cognitive semiotic dimension to the teaching of sentence structure. Such a dimension exposes learners to the cognitive factors behind grammatical meaning making and may, therefore, result in a better understanding of language structure and use on the part of learners who can become English language teachers.

action chain schema, Cognitive Grammar, figure-ground perception, event schemas, syntactic relations

1. Introduction

Syntactic relations, or the functions that constituents play in an occurrence expressed by a verb (e.g. subject, object, etc.), are surprisingly difficult for most learners of English as a foreign language to grasp, even for those majoring in Linguistics. This may be due to the fact that, despite evidence brought by cognitively oriented approaches to grammar that linguistic knowledge is an ordered inventory of constructions (form-meaning pairings) (see, for example, Langacker, 1987; Goldberg, 1995), the teaching of language structurecontinues to be placed in theories in which the atom of the sentence is the phrase. This study provides a theoretical model for teaching syntactic relations to foreign students of English Linguistics that takes this problem into account.

The model suggested is based on insights drawn from Cognitive Grammar as developed in Langacker (e.g. 1987, 1991, 1999) and elaborated on in Radden and Dirven (2007). Cognitive Grammar was selected for two reasons. First, it can facilitate the understanding of grammatical structure and use because it exposes learners to the cognitive factors underlying grammatical meaning making, such as conceptual motivation and figure-ground perception (based on the notion of salience which involves foregrounding/ backgrounding part(s) of a scene). Second, it is appropriate for the purpose of the study because it deals with constructions as schematised representations of whole events and, at the same time, shows how their meanings are made and construed through the organization of participants (see Evans & Green (2006, pp. 699-701) for an overview of the different constructional approaches to grammar). Teaching syntactic relations from the perspective of Cognitive Grammar is similar to incorporating Frame Semantics into the teaching of sentence structure (see, for example, Fillmore, 1968; Kay & Fillmore, 1999), but with the addition of a cognitive semiotic dimension. In fact, Radden and Dirven’s (2007) model of Cognitive Grammar is the product of bringing together the notions of sentence formation rules and Langacker’s constructions as conceptually motivated symbolic units. Within this model, sentence patterns form an inventory of event schemas that are characterised by a unique configuration of thematic roles (the semantic aspects of grammatical functions).

There are many proposals for using Cognitive Grammar as a tool for teaching English as a foreign language. Some important proposals concern using the framework for teaching tense, aspect and voice (see, for example, Bielak & Pawlak, 2013; Niemeier & Reif, 2008). Other proposals include using Cognitive Grammar as a complementary approach to the traditional contrastive analysis framework (Lado, 1957), which involves describing linguistic constructions in a given language and finding areas of conceptual similarities and differences between learners’ first and second language in order to determine or predict potential difficulties and errors (see the collection of papers in Knop & Rycker, 2008). What all such proposals have in common is that they draw on the notions of conceptual motivation and figure-ground perception shown in Cognitive Grammar to underlie grammatical meaning. However, teaching syntactic relations through Cognitive Grammar, which is the focus of this study, does not seem to have received attention in the literature.

What triggered the idea of the study was the observation that foreign students majoring in English linguistics make typical mistakes while taking a Syntax course. For example, when analysing sentence components in terms of function, they tend to confuse the subject complement with the object, and the object complement with the postmodifier. When analysing sentences in terms of tree structure diagrams, however, they regularly branch the two objects of a ditransitive verb from one node in the diagram, and an adverb phrase in the predicate from any node under the verb phrase (rather than from the verb phrase node itself as conceptually independent components). Such mistakes can only bemade if students fail to identify the number of participants and their different functions. The model suggested in this study may help to eliminate such mistakes because it is based on teaching syntactic relations as participant roles in meaningful events that relate to one another in a regular manner, or as category members of decreasing similarity to a prototypical concept theaction chain schema—a mental representation of force dynamics involved in the interaction between entities.

The study is organised as follows. The first section sketches the developments of work on grammatical constructions and syntactic relations that form the basis on which cognitive grammars developed. The sections to follow bring details on cognitive grammars, highlighting their treatment of syntactic relations as meaning making tools. This is followed by a model designed for teaching syntactic relations to foreign learners of English Linguistics. The study concludes with a summary of points and suggestions for further research.

2. Theoretical Prerequisites

Syntax in the classroom does not seem to reflect the relatively recent developments in the area; namely, the shift of focus from sentence formation rules to constructions as an ordered inventory of form-meaning pairings, a shift that may be described as a return to Saussure’s (1959) semiotic model of the linguistic sign (sound-meaning pairing) that includes a cognitive dimension. Although in all views on sentence structure the verb is the central element of the sentence, there are controversies that concern the relationship between the verb and the other sentence constituents.

In traditional grammars, like Chomsky’s Phrase Structure Grammar, Transformational Generative Grammar and the Minimalist Program, this relation is purely grammatical in the sense that it is divorced from its semantic and pragmatic aspects. For example, a constituent can simply play a grammatical function like the subject or object of the verb in a subject-predicate structure (see Chomsky, 1956, 1965, 1995). However, in later approaches, such as Cognitive Grammar, the verb and the other sentence constituents (the verb’s arguments) are dealt with as forming a conceptual core (in Radden & Dirven’s (2007) terminology). Within such approaches, the semantic and pragmatic aspects of grammatical patterns constitute the main focus, being rooted in perspectives like Fillmore’s Frame Semantics and Lakoff and Johnson’s Conceptual Metaphor Theory.

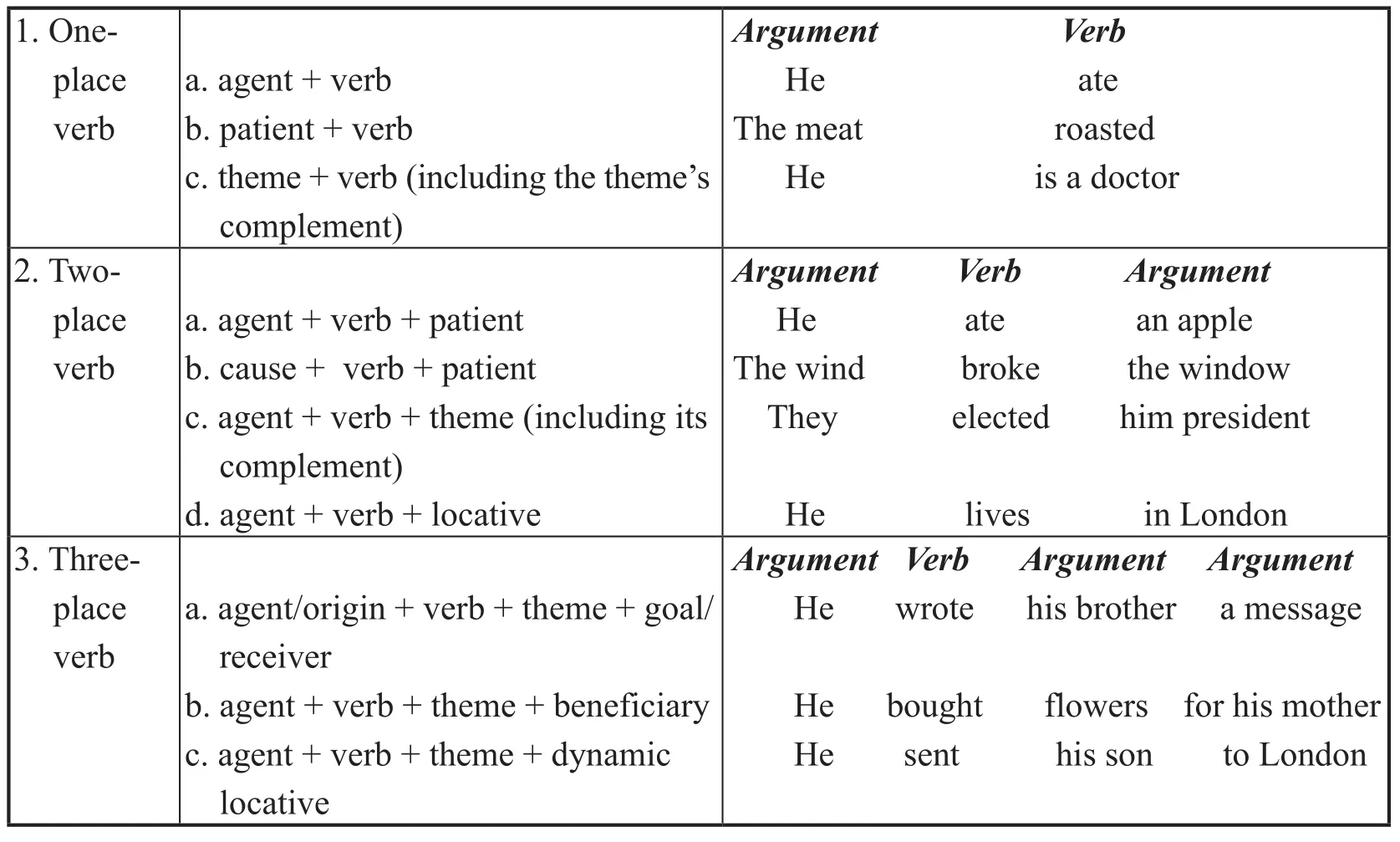

In Frame Semantics, grammatical meaning is seen as assembled through the verb and its arguments. This involves treating syntactic relations as thematic roles (e.g. AGENT, THEME, PATIENT, CAUSE, ORIGIN, LOCATION, POSSESSOR, EXPERIENCER, etc.) that are assigned by the verb. This entails showing how different verbs take different arguments. For example, a verb like ‘kick’ takes an AGENT and a PATIENT, whereas a verb like ‘love’ takes an EXPERIENCER and a THEME. In addition, different types of verbs take different numbers of arguments (valency). For example, while a verb like ‘eat’ requires one argument (an AGENT), some other verbs require at least two or three arguments. All this inturn involves viewing constructions as understood against complex knowledge structures (frames). Fillmore adopts the termsfigureandgroundfrom Gestalt psychology in order to demonstrate his point that a word or construction (figure) profiles part(s) of a frame (ground) (see Fillmore, 1968, 1982). Table (1) introduces basic sentence patterns in terms of the above view, showing that the different patterns are determined by the number of arguments that a verb can take.

Table 1. Basic sentence patterns

The first sentence pattern, one-place verb, can describe an event involving one argument, or one participant (i.e. the subject). The instance in (1.c) belongs to this pattern because the verb is followed by a complement (the subject complement) that describes the state of one participant. The second pattern is a two-place verb involving two arguments: a subject and an object. In (2.c), the second argument is complex as it includes an object complement coding the resultative effect of a transitive action. Some intransitive verbs such as ‘live’ in (2.d) require a complement like the locative to complete their meaning. As for the third pattern, it can describe events involving three participants; namely a subject and two objects or an object and a dynamic locative. The former type is a ditransitive construction and the latter is a prepositional dative construction. The ditransitive construction also applies to beneficiaries, as in (3.b).

Frame Semantics may be said to have been complemented by Conceptual Metaphor Theory (see, for example, Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Lakoff, 1987) through the exploration of frames from a cognitive point of view. On this view, meanings are concepts that are built on the basis of schematic knowledge structures, or reasoning images, representing recurring experiences (e.g. CONTAINER, SOURCE-PATH-GOAL, UP-DOWN, NEAR-FAR, PART-WHOLE). Such image-schematic structures give rise to meaningful concepts because they derive from bodily experience, which is directly meaningful. For example, our conceptualisation of the body as a container, which is reflected in a sentence likeHe hasn’t got an honest bone in his body, is based on our actual experience with our bodies (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980, p. 50). Extensions from such image schematic concepts are motivated by different types of conceptual structures such as metaphors (see Taylor, [1989]1995). Grady (1997) distinguished between two kinds of conceptual metaphors that generate concepts: primary and secondary. For instance, AFFECTION IS WARMTH (e.g.We have a warm relationship) is a primary metaphor which shows that the abstract concept AFFECTION is directly conceptualised in terms of the image-schematic concept WARMTH. This understanding is believed to arise naturally, considering that WARMTH and AFFECTION correlate in experiential terms. However, LIFE IS A JOURNEY (e.g.It is time to get on with your life) is a compound metaphor that explains the structuring of the abstract concept LIFE in terms of the more concrete concept JOURNEY. This mapping in turn has an image-schematic basis because it involves the concept of PATH. Hence, Conceptual Metaphor Theory portrays semantic structure as represented by a radial category of domains of experience (frames of knowledge) whereby more abstract experiences are understood in terms of more concrete ones in a regular manner (i.e. motivated by conceptual structures in a systematic way).

Cognitive Grammar may be said to be the result of merging insights from Frame Semantics and Cognitive Semantics within a Saussurean environment that has added a semiotic dimension to the study of grammatical constructions, as shown below (see Reda, 2016) for more insights on the Saussurean effect on the era of Cognitive Linguistics).

3. Cognitive Grammar: Constructions as a Radial Category

Cognitive Grammar, like any cognitively-oriented framework, is based on the assumption that language is inseparable from human cognition, including human perception and categorisation. Langacker (1986, p. 13) wrote that:

Like lexicon, grammar provides for the structuring and symbolization of conceptual content, and is thus imagic in character. When we use a particular construction or grammatical morpheme, we thereby select a particular image to structure the conceived situation for communicative purposes.

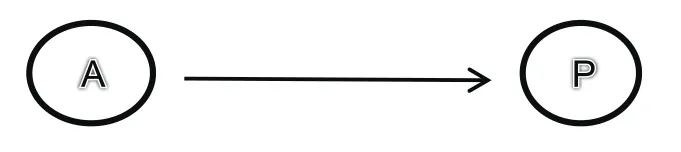

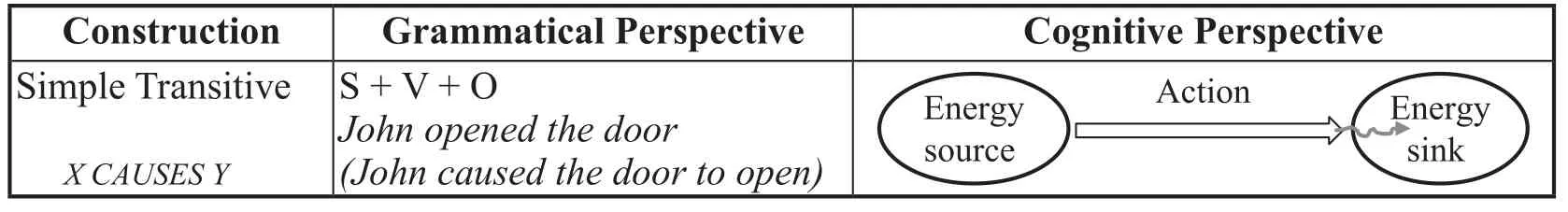

This means that constructions are like words in that their meanings derive from experiential conceptual structures. Take the transitive construction as an example. According to Langacker, this construction reflects our basic conceptualisation of action as a chain involving energy transfer from AGENT (subject as the energy source) to PATIENT (object as the energy sink). Figure (1) represents the action chain model (A stands for AGENT and P for PATIENT).

Figure 1. An adaptation of Langacker’s (2002) prototypical action chain model (Evans & Green, 2006, p. 545)

Grammatical constructions in turn reflect our categorisation of the world as things and relations. THINGS are designated by nouns and RELATIONS are designated by the other lexical classes, i.e. verbs, adjectives, prepositions and so on. These two things are assembled to express thoughts. Put differently, the conceptual core of a construction is formed by combining verbs with other participants. The structure of the conceptual core is based on the principle of figure-ground perception. This principle relates to the notion of salience which involves foregrounding/backgrounding part(s) of a scene by creating an asymmetry between the participants in a given grammatical construction (Langacker, 1987; Radden & Dirven, 2007). This asymmetry is dealt with in terms of the Trajectory (TR)-Landmark (LM) organization (which reflects the structure of the action chain schema) and connected to the notion of construal. Construal can be thought of as our ability to conceive and portray the same situation in alternative ways. According to Langacker (1987), grammatical meaning refers to how we invite the hearer to construe a situation by imposing a profile on a base, or by evoking a scene (base) and highlighting part of that scene (profile). Profiling involves elevating one of the participants in a scene to the status of trajectory (the most prominent component in a construction). Less prominent components are landmarks. For example, in the simple transitive construction, which is represented by the action chain model in Figure (1) above, the AGENT (subject) is given the status of the trajectory, whereas the PATIENT (object) is given the status of the landmark.

The manipulation of the TR-LM organization can give rise to different constructions like the passive construction in which the LM (PATIENT) is profiled, or shown as more prominent than the TR (AGENT), by placing it closer to the energy source. Similarly, the different realisations of the ditransitive construction (i.e. the double object construction and the prepositional dative construction) are the result of profiling one of the two objects by placing it closer to the energy source. The closer the component to the energy source, the more salient it is in a construction.

Hence, basic constructions can be described as the result of manipulating the action chain schema. The above examples showed one type of this manipulation that relates to the TR-LM organisation. More basic types involve increasing or decreasing the participants of the prototypical simple transitive construction. For example, the complex transitive can be included in the category of basic constructions as a member that encompasses a further participant (the object complement). The intransitive construction can thus be included in the category as a member that lacks a participant (the object). This is the structure of the teaching model developed below. Other points related to the relationship between constructions and participants are drawn from Radden and Dirven’s model of grammatical constructions as event schemas.

4. Grammatical Constructions as Event Schemas

Radden and Dirven (2007) concerned themselves with basic grammatical constructions and how they express event schemas. The most important thing about this grammar is its focus on demonstrating the non-arbitrary relationship between event schemas and thematic role configurations. Such a model can facilitate the understanding of the semiotic roles played by syntactic relations in different constructions.

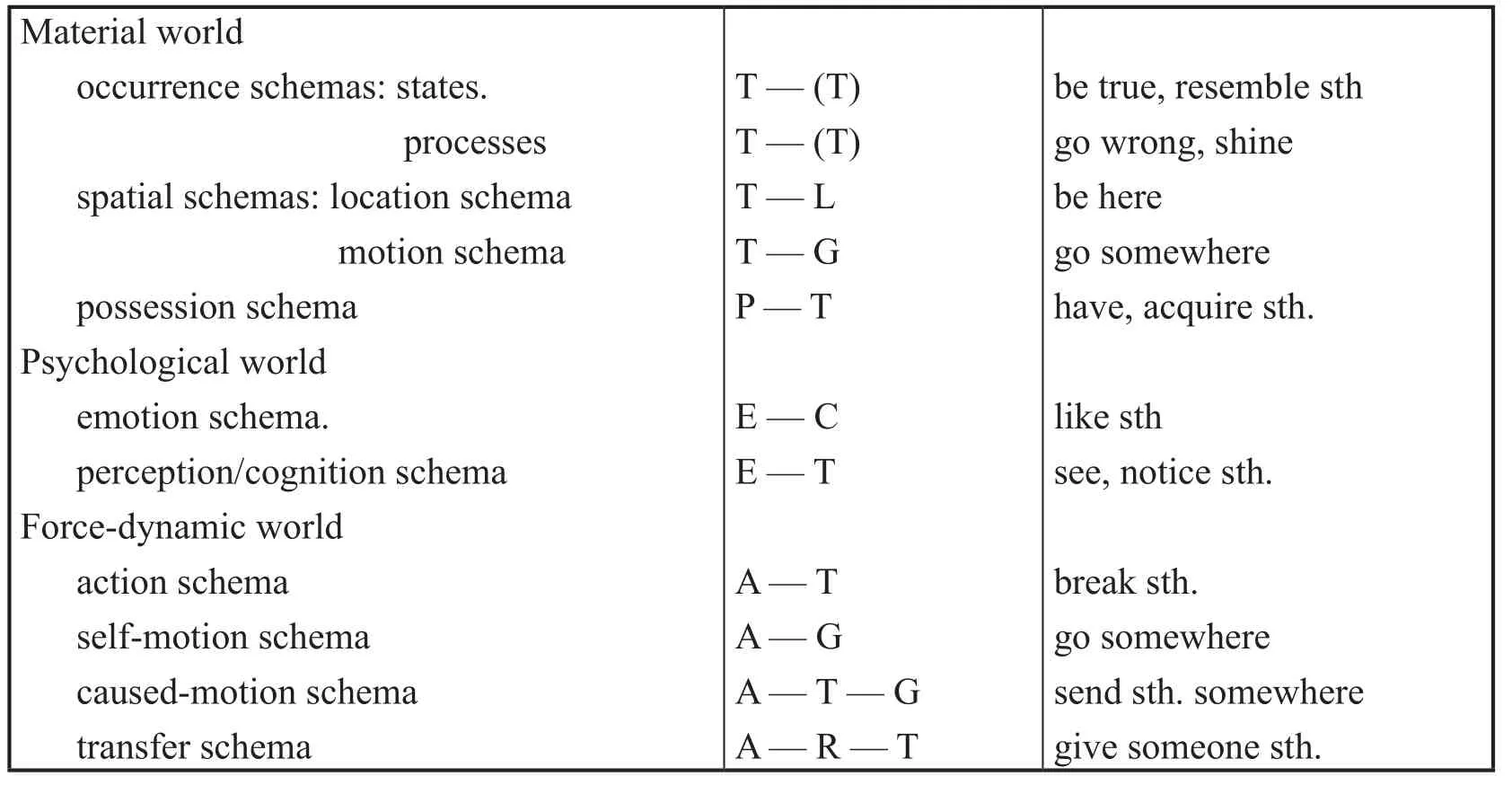

Radden and Dirven subsumed event schemas under three worlds (material, psychological and force-dynamic), showing how situations in these worlds involve a unique configuration of thematic roles, as in Table 2 (T = theme, L = location, G = goal, P = possessor, E = experiencer, C = cause, A = agent, R = recipient).

Table 2. Survey of event schemas and their role configurations (Radden & Dirven, 2007, p. 298)

As shown by this table, events in the material world comprise the following types of schemas, all of which involve the role THEME as the subject participant: 1) occurrence schemas that describe the state or process an entity is in (e.g.The food is delicious;The food is cooking), 2) spatial schemas that focus on the location and motion of a thing (e.g.The ball is in the goalandThe ball rolled into the goal), and 3) possession schemas that involve a possessor and a thing possessed, as inHe has the key.

Similarly, events in the psychological world are categorised into three types of schemas: emotion, perception and cognition. The emotion schema describes the emotional state or process that a human sentient experiences and, hence, involves the roles EXPERIENCER and CAUSE. For example, inHis stupidity amazes me, the stupidity of a person functions as the cause, or the stimulator, of the experiencer’s emotion of amazement. Perception and cognition are closely related in that they describe an experiencer’s perceptual or mental awareness of a thing and involve the rolesEXPERIENCER and THEME (e.g.I can see your point).

Finally, events in the force-dynamic world include actions, caused motions (expressed by the prepositional dative construction) and, transfers (expressed by the double object construction). The self-motion schema is a type of event that belongs to this world. It describes an agent’s initiated motion and is typically conflated with aspects of ‘manner’, as in ‘jumping’ or ‘hammering’.

Based on the above, psychological world schemas can be said to be only different from force-dynamic world schemas in regard to the participants due to their expression of metaphorical actions. Accordingly, they can be treated as metaphorical instantiations of the simple transitive in the same way as events of metaphorical transfer can be treated as instantiations of the double object constructions (e.g.He gave me a brilliant idea). Material world schemas can also be treated as manipulations of the action chain schema that involve backgrounding/foregrounding a certain aspect of an action like its result or process. In the possession schema, for example, the focus is on the final state of an action or the process that resulted in a possessor having or acquiring something (i.e. on what a possessor has or has acquired rather than on how they ended up having or acquiring something). If Radden and Dirven’s three world schemas can be organised as extensions of the action chain schema, the different instantiations and realisations of constructions can be presented in an ordered, meaningful manner that is easy to understand and analyse. This is the order adopted in building the model for teaching syntactic functions.

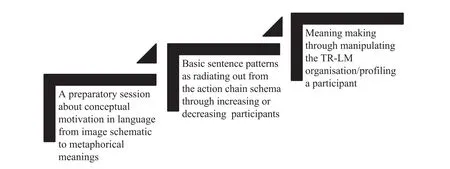

5. A Cognitive Semiotic Model for Teaching Syntactic Functions

The model suggested below consists of two phases preceded by a preparatory session that introduces students to the notion of conceptual motivation behind grammatical meaning. In the first phase, constructions are taught as a prototypically structured category. In the second phase, however, the focus is on teaching grammatical meaning making. The structure of the model is depicted in Figure 2.The notions of conceptual structures like image schemas and metaphors should be familiar to students of Linguistics as they study them in Semantics courses. The new thing in this model is that it will make students more conscious of how these conceptual structures shape the understanding and use of linguistic items.

Figure 2. A cognitive semiotic model for teaching syntactic functions

5.1 The preparatory session

This is a 2-3 hour preparatory session to be prepared with the objective of giving students the opportunity to deal with linguistic meaning as structured in terms of embodied experience. With the use of visual demonstrations like Figure 3 below, the session can start by discussing the point that meaning comes from human pre-conceptual bodily experience as infants of UP-DOWN, SOURCE-PATH-GOAL, LINK, CONTACT, SUPPORT, CONTAINER (the body is a container), PART-WHOLE, and so on.

Figure 3. A demonstration for embodied experience behind linguistic meaning

It can then be demonstrated how humans build networks of meanings on the basis of these schematic structures by using image schemas as source concepts for more abstract ones. Examples can be given from vocabulary first and then grammar.

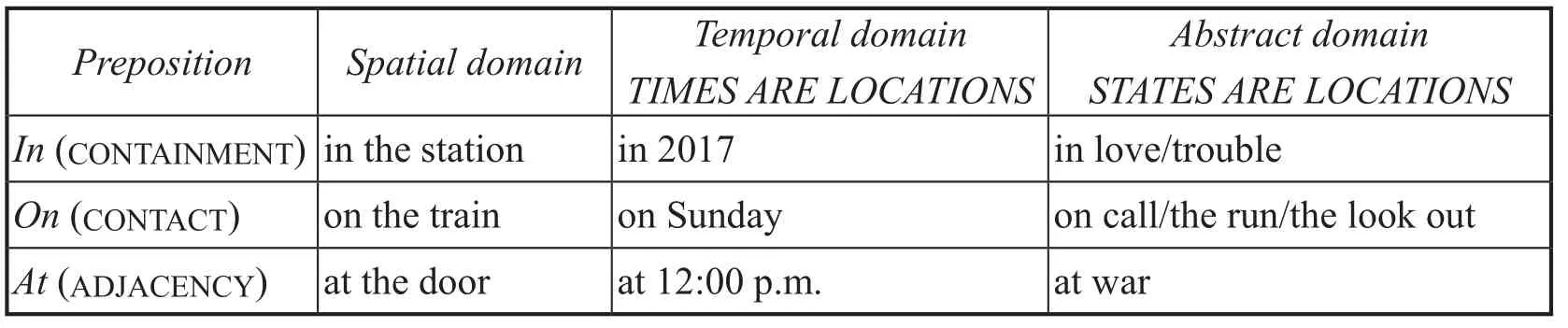

The notion of conceptual motivation behind grammatical meaning can be best demonstrated by the polysemy of prepositions. Radden and Dirven (2007) classified prepositional meanings into three domains: spatial, temporal and abstract. The spatial domain can be taught through image schemas. Then, the spatial domain can be treated as the source domain for the temporal and figurative meaning extensions. The table below is an example in which the temporal meanings of three propositions,in,onandat, are introduced through the image schemas CONTAINMENT, CONTACT and ADJACENCY. The temporal and abstract meanings are shown to be metaphorical extensions that are structured in terms of the metaphors TIMES ARE LOCATIONS and STATES ARE LOCATIONS. These metaphors involve mapping an image schematic spatial concept (be it bounded like CONTAINMENT or unbounded like CONTACT and ADJACENCY) onto the more abstract concepts of TIME and STATE.After such an activity, conceptual structures can be shown to belong to the EVENT STRUCTURE METAPHOR, whereby more abstract concepts are regularly understood in terms of imageschematic concepts. A case in point is the conceptualisation of STATES as LOCATIONS and CHANGE as MOTION. This system can then be shown to underlie complete sentences, as inHe is over the moon(STATES ARE LOCATIONS),He reached puberty(CHANGE IS MOTION) andHe got a head start in life(CAUSES ARE FORCES) (see Lakoff, 1993; Lakoff & Johnsons, 1980).

Table 3. The polysemy ofin,on, andatas motivated

The preparatory session should proceed by giving students more examples and training them to pinpoint the motivating conceptual structures behind linguistic meaning. This can be done by giving them a list of linguistic items to match with image schemas and metaphors. The following websites can be used for preparing activities for such a session: http://rhizomik.net/html/imageschemas/ and http://www.lang.osaka-u.ac.jp/~sugimoto/MasterMetaphorList/metaphors/. A more advanced activity would involve asking students to provide sentences for given image schemas and metaphors (see Appendix A for a sample activity).

5.2 Phase I: Basic constructions from grammatical and cognitive perspectives

This is a two-month phase that adds a cognitive dimension to the teaching of syntactic analysis by showing students how basic constructions (i.e. the simple and complex transitive, the ditransitive, intransitive and copular constructions) are different realisations of the action chain schema. By the end of this phase, students should be able to provide an analysis of constructions as forming a prototypically structured category whereby members are of decreasing similarity to the action chain schema.

5.2.1 The simple transitive

The simple transitive is to be presented as the prototypical construction, or as the structure that reflects the action chain schema. This involves highlighting the concepts of FORCE APPLICATION and CAUSE-EFFECT implied in this construction. Table 4 can be used for teaching the simple transitive from grammatical and cognitive perspectives.The cognitive perspective, which shows that the simple transitive involves an energy source (or an agent) whose action affects the state of an object (the energy sink), may help eliminate mistakes related to confusing the object with the subject complement in copular constructions.

Table 4. The simple transitive construction

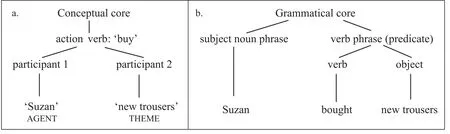

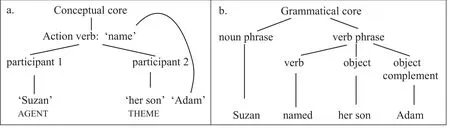

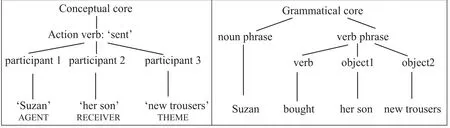

The syntactic analysis of the simple transitive in terms of a tree structure diagram can also be aided by a cognitive perspective, as in Figure 4. The conceptual core representation can make the transitive construction a meaningful event involving participants that play specific roles. Although the grammatical perspective focuses on grammatical functions, yet understanding the thematic roles can help students identify the grammatical function, especially in more complex constructions.

Figure 4. An adaptation of Radden and Dirven’s comparison between the grammatical and conceptual cores of the simple transitive (Radden & Dirven, 2007, p. 48)

The material world possession schema should be taught in the context of the simple transitive construction as students may find it hard to deal with verbs of possession as transitive verbs. As mentioned above, the possession schema can be presented as a realisation of the action chain schema in which the action or process that resulted in a possessor possesssing something is backgrounded. For example, inHe has a MercedesandShe has a diploma in Linguistics, possession can be shown as the result of a backgrounded action or process undertaken by an agent.

Emotion and perception/cognition schemas can also be introduced as figurative instantiations of the simple transitive, or as transitive constructions expressing nonphysical force dynamics. For example, figurative extensions likeShe showed compassionandThe students grasped the ideacan be taught through a metaphor like PSYCHOLOGICAL/ MENTAL ENTITIES ARE PHYSICAL OBJECTS in which non-physical entities are brought into the open as concrete physical objects. This is an important point to include because students may misidentify the syntactic functions in metaphorical sentences.

In this way, the simple transitive can be presented as the prototypical member of the category of constructions, showing that it forms a subcategory that includes the following members: the possession schema as a different realisation of the construction and the metaphorical extensions emotion and perception/cognition schemas. A peripheral member that can be added here is the occurrence schema expressing states likeShe resembles her father. This realisation can be explained as a simple transitive construction which includesthemes (one functioning as the subject and the other as the object) but lacks an agent and action. Teaching the subcategory of the simple transitive in connection with the thematic roles characterising its different members can play a vital role in helping learners understand the logic of the transitive construction and the functions of its possible participants.

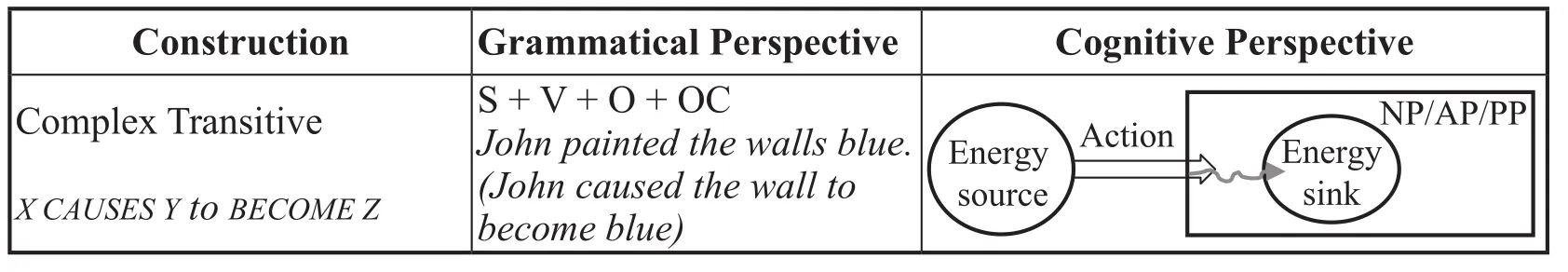

5.2.2 The complex transitive

The complex transitive construction can now be introduced by showing students that it is also structured in terms of the action chain schema, but with the addition of a further element. This element is an NP, AP or PP that functions as the object complement describing the resultative state of the object after undergoing an agentive action (see Langacker, 1999). The information in Table 5 can be used to demonstrate to students that the complex transitive is an extension of the simple transitive (X CAUSES Y) that codes anX CAUSES Y to BECOME Zevent.

Table 5. The complex transitive construction

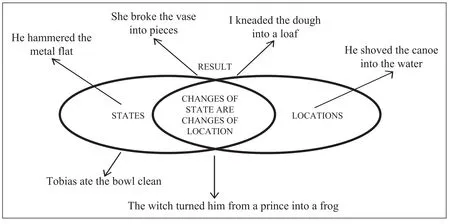

The object complement, or the additional element in the transitive construction, can further be shown to result from collapsing part of the action into the grammatical unit of an NP, AP and PP (see Langacker, 2004). This point can be demonstrated by diagramming the conceptual core of the structure, as in Figure 5. In Part a of the figure, the link between the verb ‘name’ and the NP ‘Adam’ can be explained as representative of the complementarity of meaning between the two components. Such a representation may help students to see the object complement as part of the action and branch it from the verb phrase, a point that is represented in Part b of the figure. As mentioned above, a typical error in students’ tree structure diagrams concerns the branching of the object complement from the object phrase node rather than the verb phrase, which can be due to the semantic relation that also holds between the object and its complement.Example sentences in which the three different phrases (i.e. NP, AP and PP) are used as object complements need to be given as different realisations of the complex transitive construction. Ruiz de Mendoza dealt with the object complement in terms of the metaphor A CHANGE OF STATE IS A CHANGE OF LOCATION, showing that it is a ‘result’ which may either be a change of state or a change of location, as in Figure 6 which can be used for teaching the different realisations of the complex transitive construction. Note that a typical complex transitive construction is one in which the verb’s meaning expresses the manner or tool used in the action.

Figure 5. A representation of the complex transitive as an extension of the action chain schema

Figure 6. A simplified version of Luzondo and Ruiz de Mendoza’s (2014, p. 9) representation of the family of the complex transitive construction

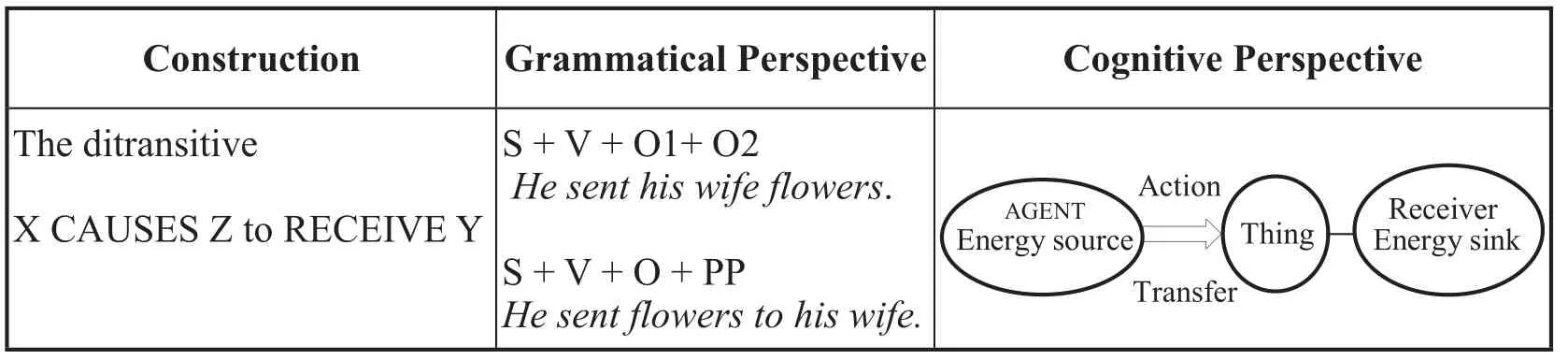

5.2.3 The ditransitive construction

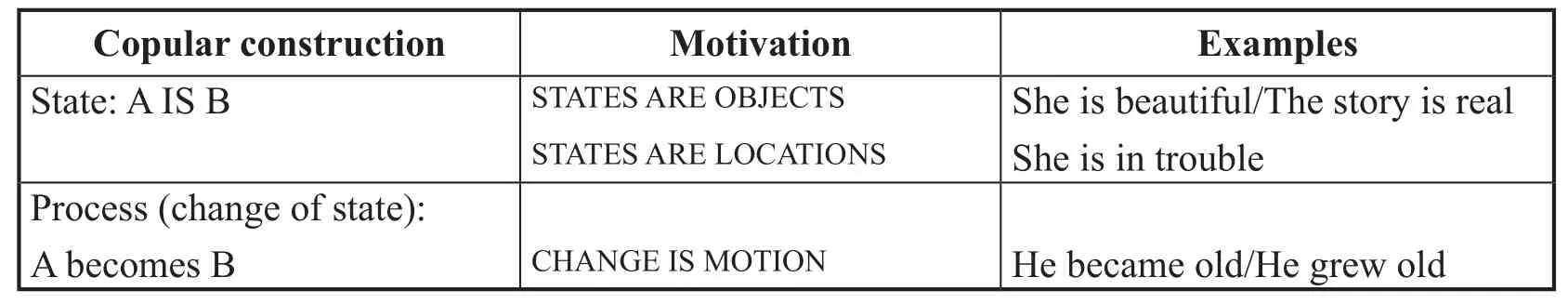

The ditransitive construction can be presented as the result of the manipulation of the action chain schema that involves the addition of a second object. The second object is needed because the construction expresses the semantics of transfer. According to Bergen and Chang (2005), three schemas cooperate in the interpretation of the ditransitive construction: FORCE APPLICATION, CAUSE-EFFECT and RECEIVE, all of which involve the schematic roles of ENERGY SOURCE and ENERGY SINK (Langacker, 1987). It is on the basis of these three schemas that the ditransitive is understood as X CAUSES Y to RECEIVE Z. The information in Table 6 can be used for teaching the ditransitive construction. The meanings of the different realisations of the construction in the table (i.e. the double object construction and the prepositional dative) are examined in the next section.

Table 6. The ditransitive construction

In addition to the above, the treatment of the ditransitive construction as less prototypical than the complex transitive should be pointed out and explained. A possible explanation is that the additional constituent in the complex transitive is part of the action (its result). In the ditransitive construction, however, there is a new participant involved with the other participants in a specific kind of action (i.e. transfer). The structure diagrams in Figure 7 below can be used to demonstrate to students that the participants in a transfer event are conceptually independent and should be branched individually from the verb phrase.

Figure 7. The ditransitive construction

As mentioned above, it is very important to expose students to the metaphorical instantiations of a construction as students may misidentify the functions of the participants in figurative events. Table 7 below summarises the literal and metaphorical meanings of the ditransitive construction. Note that the concept of transfer in the ditransitive extends from giving a material object to taking a physical or verbal action. The metaphors motivating non-literal meanings are also given in the table (see Huelva-Unternbaumen (2010) for a thorough study of the meanings of the ditransitive construction).

Table 7. Meanings of the ditransitive construction (after Huelva-Unternbaumen, 2010)

5.2.4 The intransitive constructions

The intransitive constructions can be presented as an elaboration of the action chain schema that is lacking in the schematic role ENERGY SINK. In some cases, this is simply due to profiling the action. For example, the intransitive sentenceHe sleptdiffers in meaning from the transitive oneHe had some sleepin that while the former sentence profiles the act of sleeping, the latter profiles the duration of sleep the agent had.

Material world schema that describes the process an entity is in (e.g.The food is cooking) can be taught here as a realisation of the intransitive construction in which a theme occupies the agent’s position. Spatial schemas that describe the motion and location of a thing can also be introduced here as realisations of the intransitive construction in which the focus is on the goal or location of a theme undergoing the action of moving. Teaching spatial schemas as realisations of the intransitive construction that are characterised by the thematic roles goals and locations (i.e. adjuncts) may eliminate the possibility of misidentifying these roles as objects on the part of students.

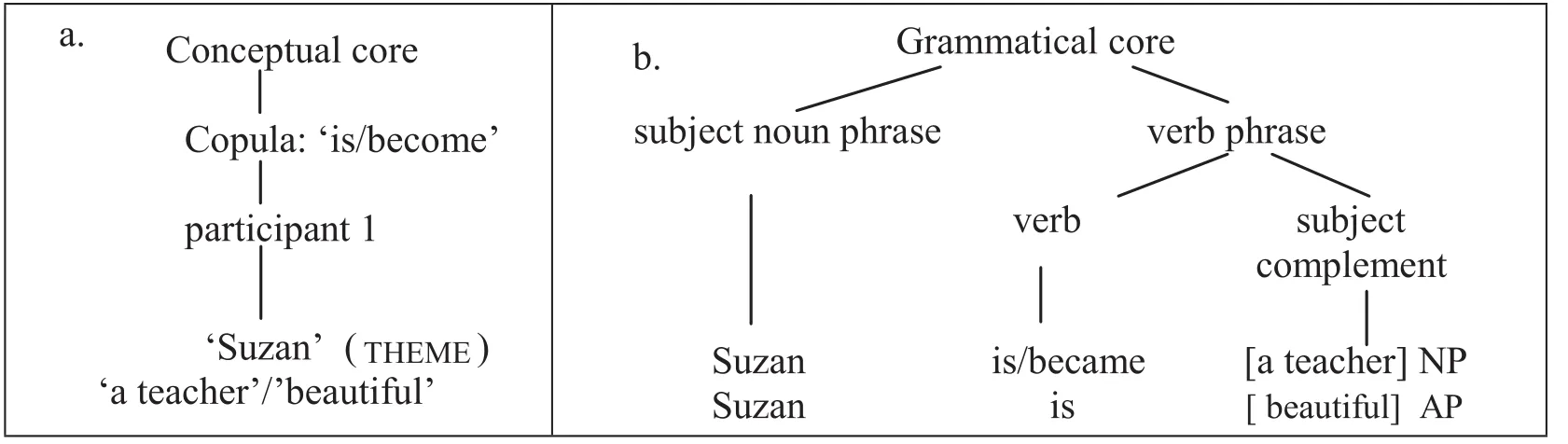

Students also typically confuse the object with the subject complement in copular constructions (or the occurrence schema ‘state’). This construction can be introduced as a realisation of the intransitive construction by showing that it is lacking in the schematic role ENERGY SINK because what is profiled is the state of the one participant (the theme). The action or process that led to that state is backgrounded. For example, inShe is a doctorthe action or process the one participant went through to become a doctor is backgrounded. Similarly, in theThe food is delicious, the act cooking (including the agent) is backgrounded. As there is no action, there is no object. Rather, there is a complement that describes the state of the participant occupying the subject position (i.e. a subject complement). The intransitive constructions considered above can be introduced with the aid of Table 8 below.

Table 8. Intransitive constructions

The diagrams in Figure 8 below can be used to show learners that copular constructions have one participant that plays the grammatical function of the subject, and that the state of the one participant is treated as the subject complement. In addition, as demonstrated by the example sentences in part b of the figure, this complement can be an NP or AP.

Figure 8. The copular construction

The information in Table 9 below can also be used to help students understand copular constructions through conceptual motivation.

Table 9. Meanings of copular constructions (after Radden & Dirven, 2007)

Phase I ends with the copular construction. Before moving on to phase II, students’understanding of basic constructions as forming a radial category needs to be examined. This includes their understanding of the different semantic and grammatical realisations of constructions. An assignment requiring from them to draw a diagram showing semantic and syntactic differences among constructions (as subcategories) can be very effective.

5.3 Phase II: Meaning making

This is also a two-month phase that provides students with meaning making activities involving manipulating the TR-LM organisation and using complex structures for participant roles. The activities involve students in making meaning, and not simply in analysing constructions. A lot can be taught through this meaning making strategy. Below are just examples of how the strategy can be applied.

5.3.1 Manipulating the TR-LM organisation

One example of using this operation is getting students to change active constructions into the passive, demonstrating to them that the passive is the result of profiling the object by placing it closer to the energy source, and that the subject can be either eliminated or made less prominent by placing it at the energy sink (e.g.The door was unlocked;The door was unlocked by the building manager). Teaching the passive construction through this meaning-making operation might be an effective way for helping students to understand the difference between active and passive sentences, which is an important point to learn in a Syntax course.

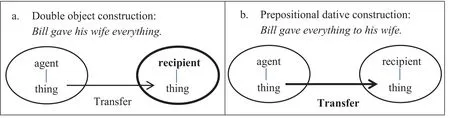

Likewise, students can be asked to use the different realisations of the ditransitive construction, demonstrating to them that any of the two objects of the verb can be profiled by placing it closer to the energy source. The second object occupies the less salient, or secondary LM elaboration site; namely, the site that is closer to the passive energy sink. An example that can be used to demonstrate the point is the sentenceBill gave his wife everythingwhich expresses the concept of transfer of possession that is built through an agent, a recipient and a thing. The placement of the recipient closer to the energy source in this sentence makes it more prominent than the things transferred. However, placing the things transferred closer to the energy source (i.e.Bill gave everything to his wife) will make the transfer of possession element more prominent than the reception of the thing, as represented in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9. Profiling in ditransitive constructions (Radden & Dirven, 2007, p. 294)

This example will make it clear to students the different realisations of the ditransitive construction (i.e. the double object construction and the prepositional dative construction) are not arbitrarily different. Rather, as Goldberg (1995) pointed out, the former construction activates a transfer-of-possession schema (X causes Y to have Z), whereasthe latter may activate a caused-motion schema.

Another activity is getting students to manipulate the TR-LM organisation in transitive constructions that can be analysed as consisting of two sub-events that jointly constitute an action chain. An example that can be used to demonstrate the point isJohn opened the doorwhich comprises the event of ‘the door opening’ and ‘john’s action of opening the door’. This example can be analysed as follows. It is a cause-effect structure that can be rephrased asJohn caused the door to open. Profiling the effect gives rise to an intransitive construction (The door opened) in which the patient is brought to the energy source, backgrounding the agent. Such an activity can contribute to a better understanding of material world schemas on the part of students (see Langacker, 1999, p. 29; Radden & Dirven, 2007).

5.3.2 Using complex structures for participant roles

In phase two, students will continue to work on the sentence patterns they learnt in phase I, but they will be asked to use complex structures for participant roles, such as using pre-modifiers and post-modifiers within an NP or AP, as is the case in the following NP functioning as subject complement (e.g.This is [the elderly woman I met in London]). Other possibilities include using nominal relative clauses as subjects and objects (e.g.[What you need] is a long holidayandYou got [what you wanted]). More possibilities include using non-finite verb phrases as post-modifiers, subjects and objects, as in the following examples respectively:I have [the motivation to learn],[Reading books] is my hobbyandI like [reading books].

Such activities need to be complemented by tree diagrams showing the structures of participant roles from cognitive and grammatical perspectives so that students show their understanding of the structures of participant roles, notwithstanding their level of complexity. Students can then be taught to add the participant role INSTRUMENT to transitive constructions (e.g.He opened the tin with a knife) and adjuncts to different constructions. What matters is that they need to be taught to deal with syntax as an area for meaning making that utilises a limited number of constructions.

6. Conclusion

This paper provided a theoretical model for teaching syntactic relations from a cognitive semiotic perspective. The model is based on insights from Cognitive Grammar, which has its roots in different perspectives on language, including the Saussurean semiotic concept of the linguistic sign. The important thing about this model is that it shows how developments in the field of Linguistics can be brought into the classroom. The suggestions made involve teaching grammatical constructions as a category motivated by the action chain schema. Within this category, the simple transitive is the prototypical member. Other members are the result of manipulating the structure of the action chain schema by increasing, decreasing, or profiling less prominent participants. The ideais to teach syntactic relations as participants in meaningful events and then create the environment for learners to use them as meaning making tools. However, an application of the model is needed to test its effectiveness.

Bergen, B. K., & Chang, N. (2005). Embodied construction grammar in simulation-based language understanding. In J.-O. ?stman & M. Fried (Eds.),Construction grammars: Cognitive grounding and theoretical extensions(pp. 147-190). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bielak, J., & Pawlak, M. (2013).Applying cognitive grammar in the foreign language classroom: Teaching English tense and aspect. Heidelberg: Springer.

Chomsky, N. (1957).Syntactic structures. The Hague: Mouton.

Chomsky, N. (1965).Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995).The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Evans, V., & Green, M. (2006).Cognitive linguistics: An introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Fillmore, C. (1968). The case for case. In E. Bach & R. Harms (Eds.),Universals in linguistic theory(pp. 1-81). New York: Holt, Reinhart & Winston.

Fillmore, C. (1982). Frame semantics. In Linguistic Society of Korea (Ed.),Linguistics in the morning calm(pp. 111-137). Seoul: Hanshin Publishing.

Goldberg, A. E. (1995).Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Grady, J. (1997).Foundations of meaning: Primary metaphors and primary scenes(Doctoral dissertation, Linguistics Dept, University of California, Berkeley). Retrieved from www. il.proquest.com/ umi/dissertations/

Huelva-Unternbaumen, E. (2010). The complex domain matrix of ditransitive constructions.Language Design,12, 59-77.

Kay, P., & Fillmore, C. (1999). Grammatical constructions and linguistic generalizations: The What’s X doing Y construction.Language,75, 1-34.

Knop, S. D., & Rycker, T. D. (Eds.). (2008).Cognitive approaches to pedagogical grammar. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lado, R. (1957).Linguistics across cultures. Michigan: Michigan University Press.

Lakoff, G. (1987).Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.),Metaphor and thought(2nd ed.) (pp. 202-251). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980).Metaphors we live by. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Langacker, R. W. (1986). An introduction to cognitive grammar.Cognitive Science,10, 1-40.

Langacker, R. W. (1987).Foundations of cognitive grammar(Vol. I). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Langacker, R. W. (1991).Foundations of cognitive grammar(Vol. II). Stanford, CA: StanfordUniversity Press.

Langacker, R. W. (1999).Grammar and conceptualization. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Langacker, R. W. (2002).Concept, image, symbol: The cognitive basis of grammar(2nd ed.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Langacker, R. W. (2004). Remarks of nominal grounding.Functions of Language,11(1), 77-113.

Luzondo, A., & Ruiz de Mendoza, F. I. (2014). Argument-structure and implicational constructions in a knowledge base. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 293824935_Argument-structure_and_implicational_constructions_in_a_knowledge_base

Niemeier, S., & Reif, M. (2008). Making progress simpler? Applying cognitive grammar to tenseaspect teaching in the German EFL classroom. In S. de Knop & T. De Rycker (Eds.),Cognitive approaches to pedagogical grammar(pp. 325-356). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Radden, G., & Dirven, R. (2007).Cognitive English grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Reda, G. (2016). Ferdinad de Saussure in the era of cognitive linguistics.Language and Semiotic Studies,2(2), 89-100.

Saussure, F. de. (1959).Course in general linguistics. New York: Philosophical Library.

Taylor, J. R. ([1989]1995).Linguistic categorization: Prototypes in linguistic theory(2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon.

Appendix A—Sample activity on conceptual motivation

Write sentences reflecting the following metaphors.

1. HAPPY IS UP; SAD IS DOWN.

2. HAVING CONTROL OR FORCE IS UP; BEING SUBJECT TO CONTROL OR FORCE IS DOWN.

Possible answers

1. I’m feeling up.

You’re in high spirits.

I’m feeling down.

My spirits rose.

I’m depressed.

He’s really low these days.

My spirits sank.

2. I have control over her.

He’s at the height of his powers.

He’s in a superior position.

He ranks above me in strength.

He is under my control.

He fell from power.

He is my social inferior.

About the author

Ghsoon Reda (ghsoon@hotmail.com) has a PhD in Applied Linguistics from Leicester University, UK, and an MA in Theoretical Linguistics from Sussex University, UK. Her research focuses on English Language Teaching, Cognitive Semantics and Semantics-Syntax interface. She has published in international academic journals, including the prestigiousELT JournalandOpen Linguistics—De Gruyter. Her recent work in which she examines conceptual projection and integration in religious texts has appeared in the 2017 Macmillan Interdisciplinary Handbook titledReligion: Mental Religion.

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年2期

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年2期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- A Glimpse of Music and Literature in French Symbolism Through Three Modern Chinese Writers—Shen Congwen, Xu Zhimo, and Liang Zongdai

- A Descriptive Study of Howard Goldblatt’s Translation of Red Sorghum With Reference to Translational Norms

- Cultural Unit Green in the Old Testament

- Self-Retranslation as Intralingual Translation: Two Special Cases in the English Translations of San Guo Yan Yi

- Innovation and Integration: Chinese Exegesis and Modern Semantics Before 1949