CIRCUIT BREAKERS

CIRCUIT BREAKERS

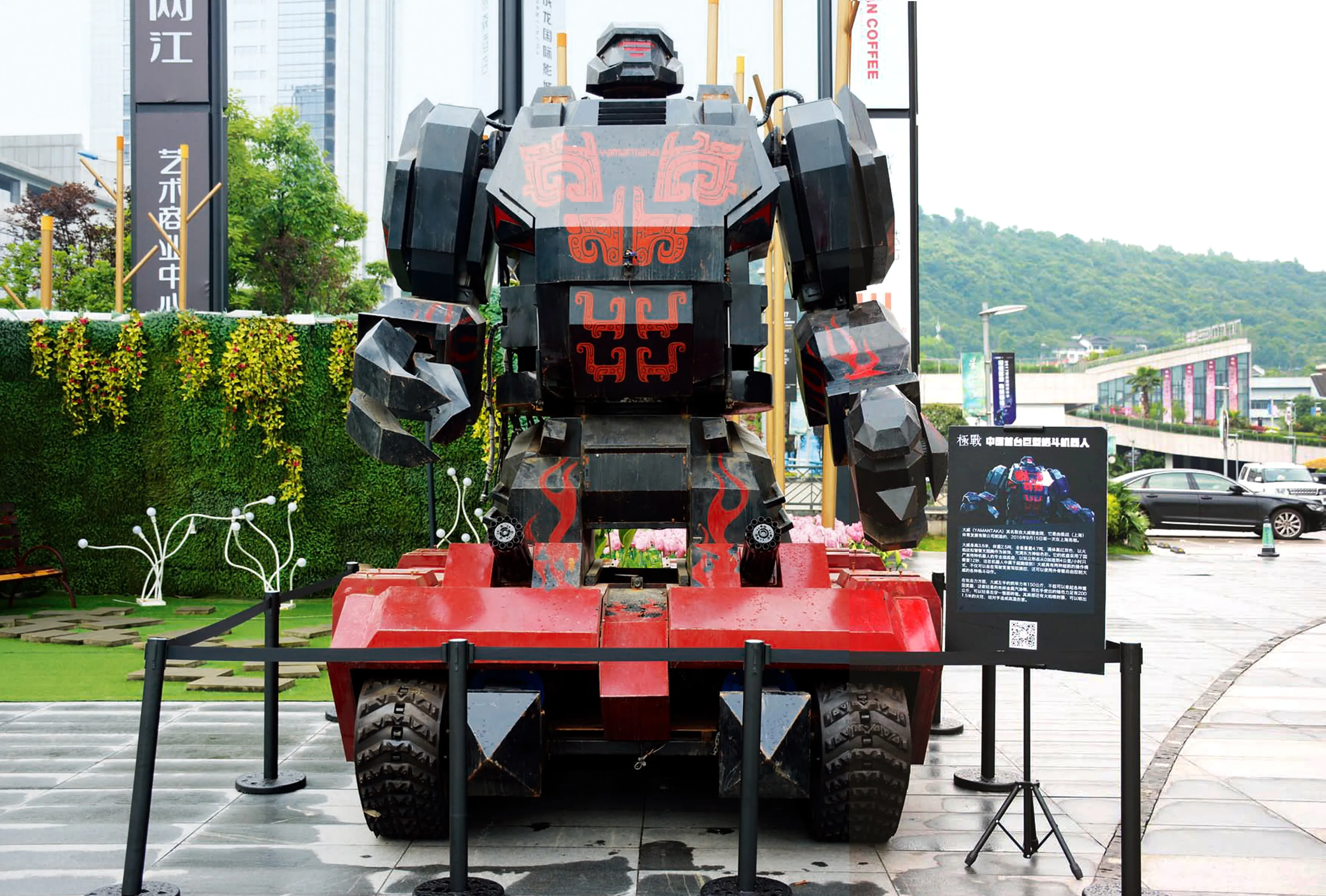

Far bigger than the actual bots used in the FMB matches, Yamantaka, built by a Shanghai robotics company in 2016, is a functional combat bot occasionally used for spectacle

When Fang Lei first went into combat, he brought Thor’s Hammer with him. But Fang made a mistake that was to prove tragically fatal. “We forgot to assemble one of the parts,”he said.

A heavily armored robot developed by Fang’s team, the Mr. O. Robot Fighting Club, Thor’s Hammer’s defining feature was, indeed, a hammer-like weapon worthy of a robotic Norse god. Its thick armor might have been able to deflect the worst effects of its opponent’s horizontal rotating blade, but the team had a more pressing problem to contend with.

“Our robot was over the weight limit, so we had to remove the armor on the sides,” Fang said. By the time the match began, the hammer was gone too—due to technical trouble—leaving a robot with no protective plating and limited avenues for attack. “As a result, our wheel was broken by our opponent and we lost all the matches after that. We felt heartbroken,” Fang said.

Fang’s team is among dozens in China—and soon, it’s hoped, the world—participating in Major League Fights (MLF), the robo-fighting tournament series run by the Fighting My Bots (FMB) league. Founded in 2015, FMB is at the forefront of a push to take China’s robot combat global. But if their entrants seem ill prepared, that’s probably because it’s all a bit new—at least in China.

FMB’s first event was in late 2016 and organizers have been cobbling together rules and requirements for matches ever since, while trying to maintain some flexibility in terms of robot design.

These efforts will kick into high gear in August, when an MLF warm-up event takes place in Guangzhou. A FMB tournament will follow in September in Xi’an, before organizers set their sights on the finals in October.

According to FMB’s official website, the goal is to move beyond tournament leagues and “make the fighting ring an incubator for scientific, humanistic, and artistic innovation.” The plans involveturning FMB into an “entertainment media brand” producing reality shows, live broadcasts, and television dramas, while providing workspaces and venture capital for a “comprehensive eco-system of robot-themed innovation.”

Forget Transformers. David Dawson gets in the ring with China’s real-life robot warriors

機(jī)器人格斗大賽點(diǎn)燃科技熱情

Chinese fan site Gedoumi (“Combat Fanatics”), which covers martial sports in an occasionally nationalistic tone, complained that, at the height of US seriesBattle Bots’ popularity in the early 2000s, “the situation in China was a vacuum,” with robot mêlées limited to student hobbyists.

Announcing FMB’s latest tournament in an April 2017 article titled “Chinese Combat Robots Have Declared Against Japan and the US!” the site crowed “the teams’ imagination is not in any way weaker than foreign teams.” Historically, though, China’s robotics industry has been in default catch-up mode to the US.

Xianxingzhe (先行者, “Pioneer”), China’s first bipedal humanoid robot, was unveiled in 2000 to some fanfare in China and amusement abroad due to its vintage appearance and rudimentary functions. The same year saw the launch of the country’s first robotics competition, the China Intelligent Robot Contest (or xPartners Cup), followed by numerous robotics tournaments, few of which focused on combat.

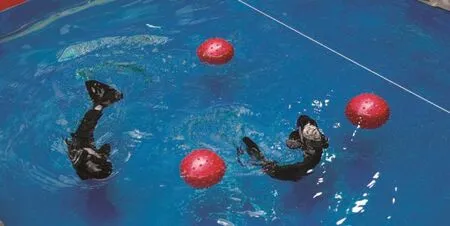

The RoboCup China Open, first held in 2006, included events from safety-and-rescue obstacle courses to soccer tournaments (an event broadcast on CCTV). There are also regular water polo matches featuring electronic fish, and robot chef tournaments.

An FMB tournament in Nanchang, Jiangxi, in April 2017 was the first to feature other countries, according to FMB organizer Chen Xin. Teams from the US, Brazil, and Turkey, some of them veterans of the international robot circuit, were among 40 competitors, some sponsored by corporations, with 10 engineers and designers working behind the robots’ringside controllers. But many are amateur outfits, who work in robotics but enter competitions on their own dime.

As Jiang Jun, the engineer on Fang’steam, points out, each robot fighter can cost around 30,000 to 40,000 RMB to build, discounting labor costs. While the team compete for cash prizes of 15,000 RMB in the 15-kilo class or 40,000 RMB (60 kilos), most are in it for the love of the sport as well as the chance to hone their robotcrafting skills.

At this stage of the sport, design options are still flexible, with less emphasis on limitations and more on fair play: Magnets or Electromagnetic Pulses (EMPs), which would fry the electronics of any bot in the vicinity, are not allowed. Liquids are not permitted—you couldn’t attach a water pistol to your robot—but a flamethrower is fine. Another rule bans any objects independent of the main body of the bot—no projectile weapons, or multiple robots acting as a swarm.

The results are decided by judges—if one robot is incapacitated and the other isn’t, that’s an easy decision, but once a match goes on for three minutes, then the judges must decide which put up a better fight according to their criteria.

Chen says that the rules basically follow the principle of being fair and open.

“Our aim is to promote robotic technology, so we adjust our rules based on this, in order to encourage the participants to use the newest technology,” Chen said. “Once we find anyone breaks the rules or exploits loopholes in those rules, our judges can respond accordingly.”

And the technology can scale up pretty fast, with plenty of room for invention and rapid evolution as weaknesses are discovered. Take, for example, the common “wedge”design, familiar to any casual viewer of televised tournaments such as the BBC’s long-runningRobot Wars.

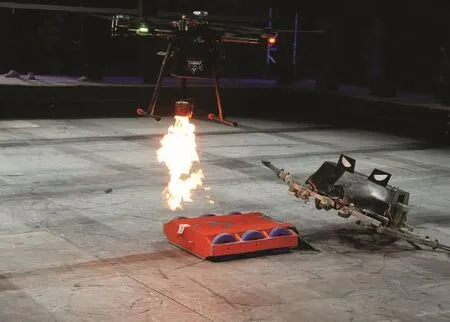

Given the fact most robots are wheeled, a handy counter-strategy is a flat robot with a slanted front that can simply ram and flip the opposing robot, leaving it as helpless as a tortoise. The wedge design is easy—some wheels under a flat platform to maximize stability, and no weapons needed—and very dull. But while it may be effective against most wheeled robots, it suddenly runs into trouble when facing off against a drone with a downward-facing flamethrower.

Yes—robots are permitted to fly, and even if a flying flamethrower doesn’t succeed in totally incapacitating the helpless wedge, scorching it might be enough to give the win.

“The robots are getting more and more sophisticated,” Chen points out. “In terms of the technology…it’s already beyond many people’s imagination.” This advanced tech is being recognized in the ring, as FMB CEO Zhang Honglei told People’s Daily Online in April. “The prize for best technology targets specific types each year,” Zhang said. “In 2016, the prize targeted multi-ped robots and those with two arms.”

The next step is greater audience engagement. A match in Beijing in April was broadcast on CCTV 5, but, despite increasing censorship and restrictions on video content, online streaming is already proving effective at targeting the relatively young audience that’s happy to watch robots battling it out on a mobile screen via platforms such as Youku and Bilibili. FMB’s media outreach has been surprisingly international given their relative infancy, with numerous FMB-focused discussions active on Reddit, including clips of previous fights.

Meanwhile, Chen points out that next year, FMB hopes to double the number of fights, with a New Year’s event planned in the tropical getaway of Hainan Island after the finals in October. Organizers hope that the sky’s the limit—although flying robots have already made their debut.

Robot fish playing water polo at the 2013 International Underwater Robot Competition in Ningbo

A drone-bot roasts its opponent

Rushed repairs and inspections are common between matches