Epidemiological study of hypertensive retinopathy in the primary care setting: Retrospective cross-sectional review of retinal photographs

Lap-kin Chiang, Michael K.C. Yau, Cheuk-wai Kam, Lorna V. Ng, Benny C.Y. Zee

1. Family Medicine and General Outpatient Department, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China

2. The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care,The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Epidemiological study of hypertensive retinopathy in the primary care setting: Retrospective cross-sectional review of retinal photographs

Lap-kin Chiang1, Michael K.C. Yau1, Cheuk-wai Kam1, Lorna V. Ng1, Benny C.Y. Zee2

1. Family Medicine and General Outpatient Department, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China

2. The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care,The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Objective:The objective is to estimate the prevalence and grading of hypertensive retinopathy in the primary care setting; examine the patient characteristics associated with hypertensive retinopathy; and examine the association of hypertensive retinopathy and other hypertension complications.Methods:This is a retrospective cross-sectional study. Subjects included adult hypertensive patients with available and gradable retinal photographs.Results:Two hundred fifty-six male hypertensive patients (34.3%) and 491 female hypertensive patients (65.7%) were included. The average duration of hypertension was 7.2 years, and 49.8% and 41.2% of patients were taking one or two antihypertensive medications respectively.Among 1491 qualified retinal photographs (744 right eye and 747 left eye), 24.9%, 62.6%, and 12.5% were classified as showing normal, mild, and moderate hypertensive retinopathy respectively. The three commonest retinal signs were generalized or focal arteriolar narrowing (650 cases,43.6%), hard exudates (168 cases, 11.3%), and opacity (copper or silver wiring) of the arteriolar wall (166 cases, 11.1%). Patients older than 61 years, having hypertension for more than 15 years,or taking three or more antihypertensive medications were significantly associated with hypertensive retinopathy (P<0.05).Conclusion:In a primary care clinic in Hong Kong, 77.1% of hypertensive patients had hypertensive retinopathy. Advanced hypertensive retinopathy was the commonest target organ damage for hypertensive patients in a primary care clinic.

Hypertensive retinopathy; retinal photograph; primary care

Introduction

Hypertension remains a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease, the greatest cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Poorly controlled hypertension results in damage to the retinal microcirculation, and therefore recognition of hypertensive retinopathy (HTR)may be important in cardiovascular risk stratification for hypertensive individuals [1].Evidence from studies showed that retinopathy signs were related to the risk of stroke,including incident clinical stroke, ischemic stroke, and subclinical silent lacunar infarct[2–7]. The prevalence or incidence rate of various retinal microvascular lesions of in between 2% and 51% have been reported by previous studies [2, 8–11]. Various studies have shown that retinal microvascular changes can be reliably documented by retinal photographs [8, 9, 12–14].

The Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection,Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure indicates retinopathy as target organ damage [15]. The WHO–International Society of Hypertension [16], the British Hypertension Society guidelines [17], and the European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology guideline [18] indicate HTR grades III and IV as target organ damage.

In contrast to diabetic retinopathy, there is no widely accepted classification or definition of HTR [19]. International management guidelines are not consistent in this respect [19].The strongest evidence for the usefulness of HTR for risk stratification is based on its association with cardiovascular outcomes such as stroke and myocardial infarction [20].Epidemiological data on HTR were lacking in the primary care setting. This study aimed to estimate the prevalence and grading of HTR in the primary care setting, to examine the patient characteristics associated with HTR, and to examine the association of HTR and other hypertension complications.

Methods

This is a retrospective cross-sectional survey; see the Appendix for the study flowchart. All hypertensive patients who had completed hypertension complication screening during the period from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2013 at one regional primary care clinic in Hong Kong were included. There were approximately 7000 hypertensive patients being treated by the clinic during the study period, and they were arranged for complication screening in a triennial cycle. HTR was examined by use of a direct ophthalmoscope by a clinician or by retinal photographs.Retinal photographs were taken by a retinal photo camera (model Topcon TRC-NW8) at resolution of 3216X2136 after pupil dilation. Hypertensive patients with available and gradable retinal photographs were recruited, whereas patients with the comorbidity of diabetes mellitus or patients whose retinal photographs were either lost or of poor quality for interpretation were excluded.

Outcome measures

Relevant data – namely, smoking status, number of years diagnosed hypertension, number of antihypertensive agents,comorbidities, and the summary of complication screening were retrieved from the patient computerized medical system. All retinal photographs were reviewed and graded by two researchers independently. The researchers had completed training in retinal photograph viewing and grading. Retinal findings were recorded as an exact description based on the visual impression of the researchers and then graded according to the classification proposed by Wong and Mitchell [20].If a discrepancy in grading existed between the two researchers, a consensus would be reached after a group discussion by at least three researchers. All retinal photographs (both available right and left eyes) were included for grading. The eye with higher severity of grading determined the grade of HTR for the patient.

Definition of HTR

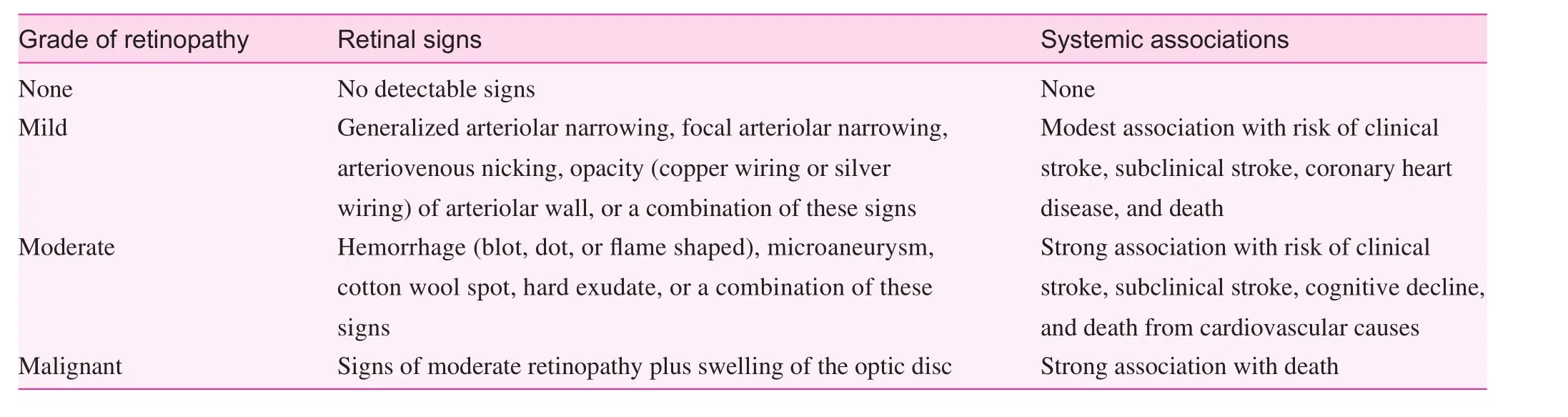

The definition of HTR was based on the Wong and Mitchell[20] classification (Table 1).

Table 1. Wong and Mitchell classification of hypertensive retinopathy

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including the mean, standard deviation(SD), frequency, and percentage were used to summarize the characteristics of the variables. Descriptive information for each of the explanatory variables are presented. Bivariate association of the variables with HTR was assessed by the chisquare test for categorical variables. Multivariate analysis with logistic regression was applied to examine the predictive factors. APvalue of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.Data analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 21.0, SPSS, United States).

Research ethics

The study was approved by the Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee of the Hong Kong Hospital Authority.

Results

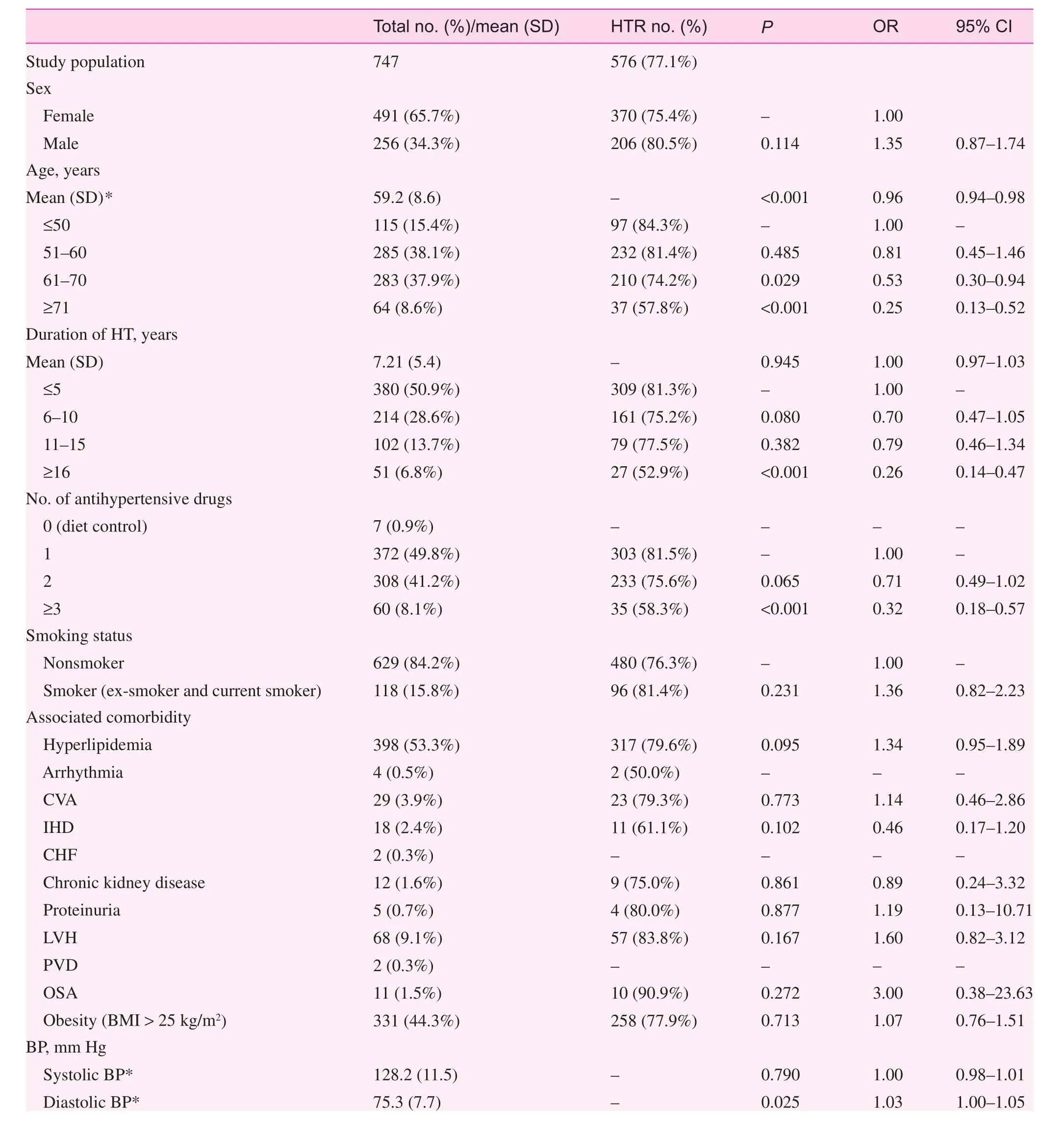

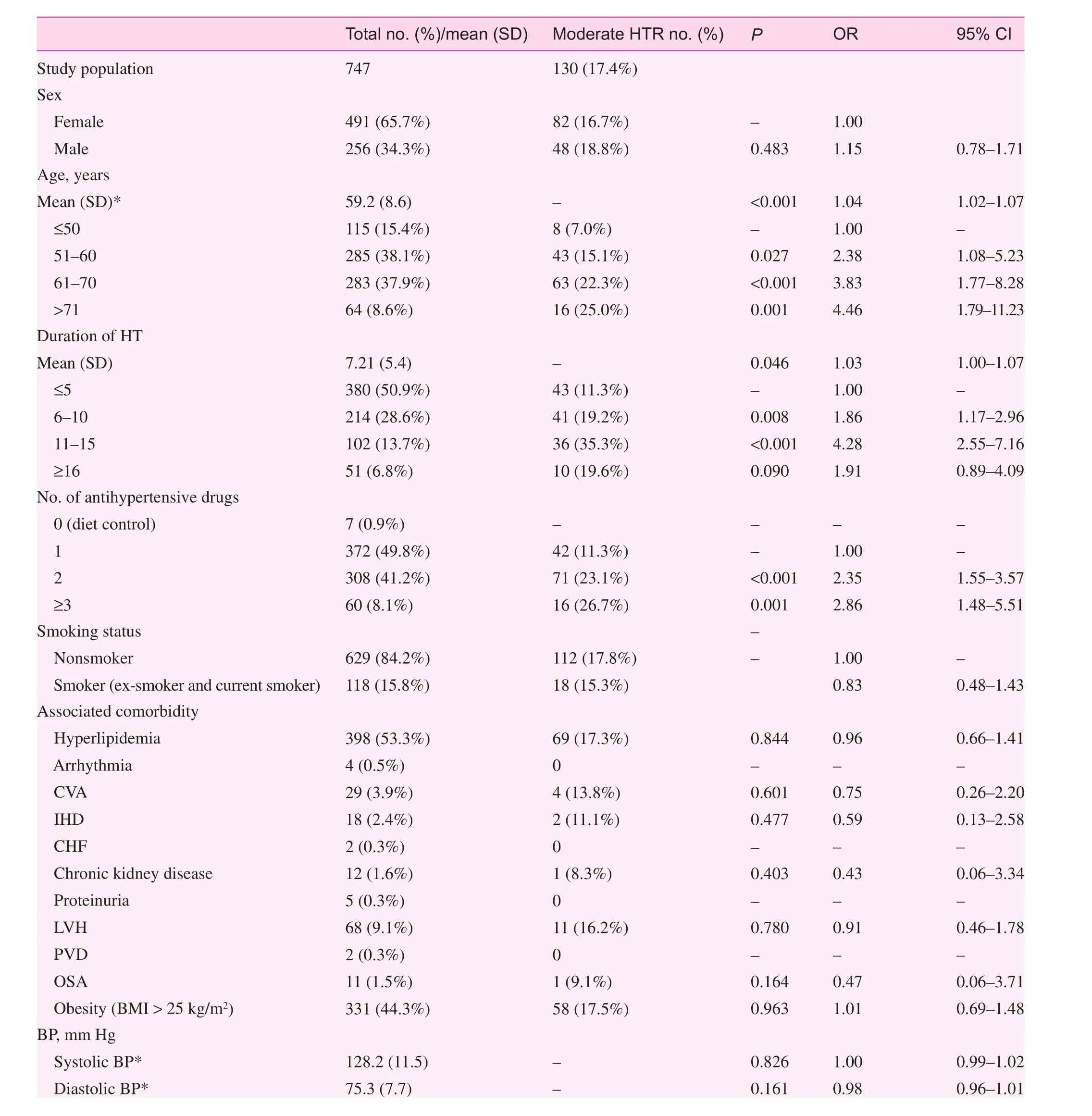

Two hundred fifty-six male hypertensive patients (34.3%) and 491 female hypertensive patients (65.7%) were included, with a mean (SD) age of 59.2 (8.6) years (Table 2). The average duration of hypertension was 7.2 years, and 49.8% and 41.2%of patients were taking one or two antihypertensive medications respectively. The three leading associated comorbidities were dyslipidemia (53.3%), obesity (44.3%), and a history of stroke (3.9%). The mean (SD) blood pressure was 128.2(11.5)/75.3 (7.7) mm Hg.

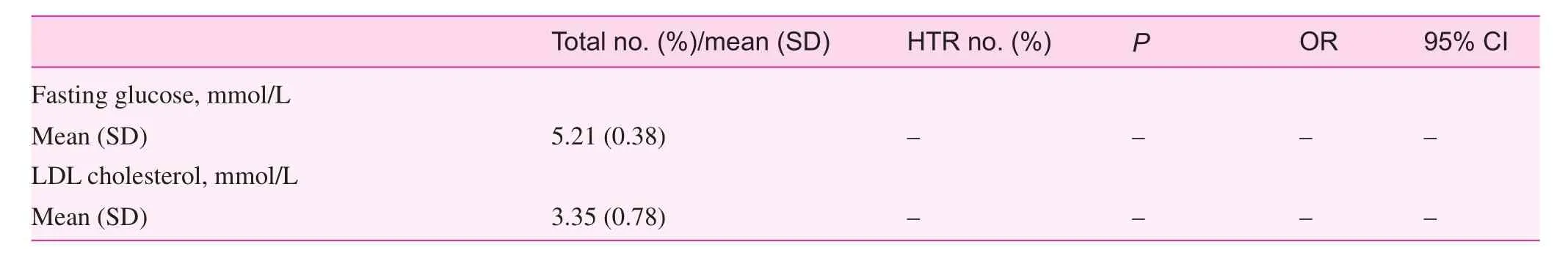

Hypertensive retinopathy

One thousand four hundred ninety-one retinal photographs(744 right eye and 747 left eye) were qualified for classification(Table 3). Among these 24.9%, 62.6%, and 12.5% were classified as showing normal, mild, and moderate HTR respectively.No severe retinopathy was reported. The three commonest retinal signs were generalized or focal arteriolar narrowing(650 cases, 43.6%), hard exudates (168 cases, 11.3%), and opacity (copper wiring or silver wiring) of the arteriolar wall(166 cases, 11.1%). No swelling of the optic disc was reported.Overall, 576 patients (77.1%) had any HTR and 130 patients(17.4%) had moderate HTR.

Patient characteristics associated with HTR

Table 2 illustrates that 77.1% of patients (576 of 747) had HTR of any severity. Bivariate analysis with the chi-square test revealed that hypertensive patients older than 61 years, having hypertension for more than 15 years, or taking three or more antihypertensive medications were negatively associated with HTR. By means of univariate logistic regression analysis, diastolic blood pressure significantly predicted HTR (P=0.025).

Multivariate analyses by a logistic regression procedure were applied to determine the patient characteristics associated with HTR. Factors including age, duration of hypertension, number of antihypertensive drugs, and diastolic blood pressure were included for analysis. The final fitted model revealed that patient age was statistically significantly associated with HTR. The odds ratio was 0.96 (95% confidence interval 0.94–0.98,P<0.001).

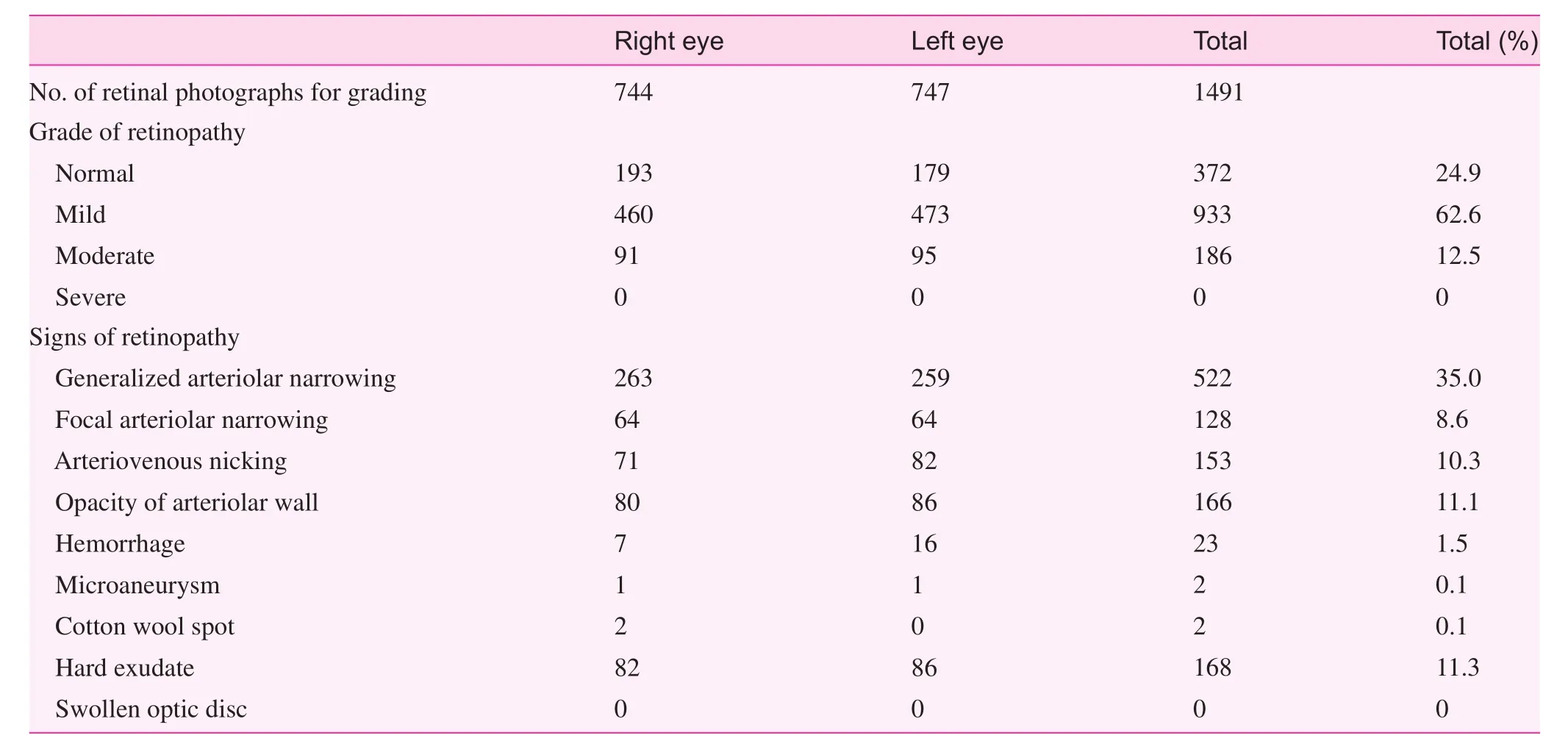

Patient characteristics associated with moderate HTRTable 4 summarizes the patient characteristics associated with moderate HTR. One hundred thirty patients (17.4%) had moderate HTR. Advanced patient age, longer duration of hypertension, and taking a greater number of antihypertensive agents were statistically significantly associated with moderate HTR.Both systolic and diastolic blood pressure were associated with moderate HTR.

Multivariate analyses by a logistic regression procedure were applied to determine the patient characteristics associated with moderate HTR. Factors including age, duration of hypertension,and number of antihypertensive drugs were included for analysis.The final fitted model revealed that patient age was statistically significantly associated with moderate HTR. The odds ratio was 1.04 (95% confidence interval 1.02–1.06,P=0.001).

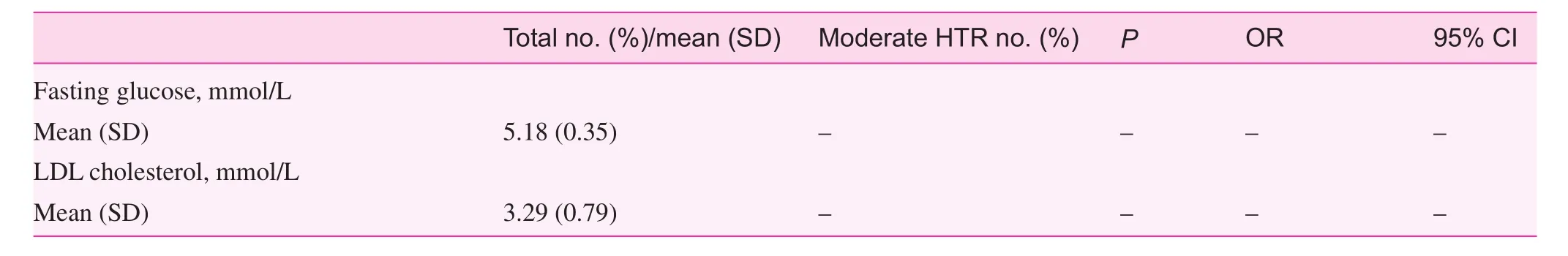

Hypertension complications

As illustrated in Table 5, the hypertension complications were reported as either target organ damage or associated clinical conditions according to the European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology guidelines[18]. The leading three complications or target organ damage were advanced HTR (17.4%), heart disease (7.1%), and cerebrovascular disease (3.9%).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study revealed that HTR was prevalent among hypertensive patients in a primary care setting.

Table 2. Patient demographics and association with hypertensive retinopathy

Table 2 (continued)

Table 3. Retinal photography outcomes

Advanced HTR (moderate or malignant retinopathy) was the commonest hypertensive target organ damage.

'Hypertensive retinopathy' (HTR) refers to retinal microvascular signs that develop in response to raised blood pressure[14, 21–23]. It is predictive of incident stroke, congestive heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality independently of traditional risk factors [2, 23]. The initial response to raised blood pressure is a vasoconstrictive phase, which manifests itself clinically as generalized retinal arteriolar narrowing. The subsequent arteriosclerotic phase is characterized by hyperplasia of the tunica media, hyaline degeneration of the arteriolar wall,and intimal thickening, which manifest themselves clinically as vessel attenuation, increased arteriolar reflex, arteriovenous nicking, and increased tortuosity of arterioles. With more pronounced high blood pressure, the blood–retinal barrier breaks down, resulting in exudation of blood (hemorrhage), lipids(hard exudates), and subsequent ischemia of nerve-fiber layers(cotton wool spots). In the setting of severely high blood pressure, raised intracranial pressure and concomitant optic nerve ischemia can lead to disc swelling (papilledema).

Table 4. Patient demographics and association with moderate hypertensive retinopathy

Table 4 (continued)

Table 5. Hypertension target organ damage or associated conditions

The prevalence of HTR in our study was remarkably higher than in previous studies; that is, 2–15% [8–11]. However, those were population-based studies including individuals with or without a history of hypertension. In the study by Ong et al. [2]involving hypertensive participants, the prevalence of mild HTR was 46.6% and that of moderate HTR was 5.1%. The higher prevalence in the more recent studies was probably due to the higher sensibility of photography as compared with clinical ophthalmoscopy for detecting certain signs of retinopathy [20].

Our study revealed that patient age, duration of hypertension, and number of antihypertensive medications taken were negatively associated with any HTR; however, those factors were positively associated with moderate HTR. The exact reasons for this reverse relationship are not clear. Findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study [24], the Blue Mountains Eye Study [9], and the Beaver Dam Eye Study [8]indicate that the pathogenesis of retinal arteriolar changes (focal and generalized arteriolar narrowing, and arteriovenous nicking) was distinct from that of severer signs of HTR (hemorrhage, hard exudates, or cotton wool spots). Evidence revealed that generalized retinal arteriolar narrowing (i.e., graded as mild HTR) appeared to be more prominent in younger individuals than in older individuals with similar severity of hypertension[14]. Clinical trials showed that the signs of HTR regressed with good control of blood pressure [25, 26]. It was also suggested that antihypertensive medication that had direct beneficial effects on the microvascular structure (e.g., angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors) would reduce the damage caused by retinopathy beyond the reduction effected by lowered blood pressure [20]. The participants in our study were all hypertensive patients, who had an average of 7.2 years of hypertension,and 99.1% were taking antihypertensive medications. However,they achieved good hypertension control, with a mean blood pressure of 128.2/75.3 mm Hg. It is probable that the high proportion of mild HTR (i.e. 62.6%) might be reduced with time after attainment of good control of blood pressure.

Hypertension is prevalent in Hong Kong. The Population Health Survey 2003/2004 of the Department of Health revealed that approximately 27% of the population aged 15 years or older had increased blood pressure [27]. Among those in whom hypertension had been diagnosed, 70% were prescribed blood-pressure-lowering medication, but only about 40% of those receiving treatment attained control of their blood pressure [28]. Worldwide, hypertension awareness, treatment, and control remain less than optimal [29]. Recognition of HTR may be important in cardiovascular risk stratification and in prediction of other cardiovascular complications of hypertensive patients [1, 2]. Physicians should undertake more vigilant monitoring of the cardiovascular risk in patients with mild retinopathy, or adopt an aggressive approach to risk reduction in patients with moderate retinopathy. Urgent antihypertensive treatment and ophthalmologist care should be initiated for patients who have severe retinopathy [20].

As stated by Wong and Mitchell [20], the data from HTR studies might support the development of a photographic classification of HTR that would be similar to the photographic grading of diabetic retinopathy. Secondly, the information will also promote additional prospective studies that aim to demonstrate an independent association of HTR with various cardiovascular outcomes. This information will be important when one is formulating a clinical protocol, planning screening services, or projecting cost, especially in the face of an escalating awareness of hypertension care in our local community.

This study has limitations. It is a retrospective survey, not all hypertensive patients have eligible retinal photographs, and the aquisition of retinal photographs is ordered by all physicians in the department; therefore a patient selection bias cannot be excluded. This study involved patients from one primary care clinic only, and it is uncertain whether this study group represents the whole patient population in the primary care setting.

Conclusion

In a primary care clinic in Hong Kong, 77.1% hypertensive patients had HTR. Advanced HTR was the commonest target organ damage for hypertensive patients in the primary care clinic. Multivariate analysis revealed that patient age was the only factor significantly associated with HTR.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians for supporting this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

Hong Kong College of Family Physicians Research Seed Fund.

1. Chatterjee S, Chattopadhya S, Hope-Ross M, Lip PL. Hypertension and the eye: changing perspectives. J Hum Hypertens 2002;16(10):667–75.

2. Ong YT, Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BEK, Mitchell P, Sharrett AR,et al. Hypertensive retinopathy and risk of stroke. Hypertension 2013;62(4):706–11.

3. Wong TY, Klein R, Nieto FJ, Klein BEK, Sharrett AR, Meuer SM, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and 10-year cardiovascular mortality: a population-based case-control study.Ophthalmology 2003;110(5):933–40.

4. Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Wong TY, Smith W, Klein R, Leeder SR.Retinal microvascular signs and risk of stroke and stroke mortality. Neurology 2005:65(7):1005–9.

5. Witt N, Wong TY, Hughes AD, Chaturvedi N, Klein BEK, Evans R, et al. Abnormalities of retinal microvascular structure and risk of mortality from ischaemic heart disease and stroke. Hypertension 2006;47(5):975–81.

6. Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, Couper DJ, Klein BEK, Liao DP, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions, retinopathy, and incident clinical stroke. J Am Med Assoc 2002;288(1):67–74.

7. Yatsuya H, Folsom AR, Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BEK, Sharrett AR. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and risk of lacunar stroke: Atherosclerosis Risk in Community Study. Stroke 2010;41(7):1349–55.

8. Klein R, Klein BEK, Moss SE. The relation of systemic hypertension to changes in the retinal vasculature: the beaver dam eye study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1997;95:329–48.

9. Wong JJ, Mitchell P, Leung H, Rochtchina E, Wong TY, Klein R.Hypertensive retinal wall signs in a general older population: the blue mountains eye study. Hypertension 2003;42(4):534–41.

10. Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BE, Meuer SM, Hubbard LD. Retinal vessel diameter and their associations with age and blood pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44(11):4644–50.

11. Wong TY, Hubbard LD, Klein R, Marino EK, Kronmal R, Sharrett AR, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and blood pressure in older people: the cardiovascular health study. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86(9):1007–13.

12. Couper DJ, Klein R, Hubbard L, Wong TY, Sorlie PD, Cooper LS, et al. Reliability of retinal photographs in the assessment of retinal microvascular characteristics: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133(1):78–88.

13. Sharrett AR, Hubbard LD, Cooper LS, et al. Retinal arteriolar diameters and elevated blood pressure. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Community Study. Am J Epidemiol 1999;150(3):263–70.

14. Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BEK, Tielsch JM, Hubbard L, Nieto FJ.Retinal microvascular abnormalities and their relationship with hypertension, cardiovascular diseases and mortality. Surv Ophthalmol 2001;46(1):59–80.

15. Chobonian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA,Izzo JL, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. J Hypertens 2003;42(6):1206–52.

16. World Health Organization/International Society of Hypertension Writing Group. 2003 WHO/ISH statement on management of hypertension. J Hypertens 2003;21(11):1983–92.

17. Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ, Davis M, McInnes GT,Potter JF, et al. British hypertension society guidelines for hypertension management 2004 (BHS-IV): summary. BMJ 2004;328(7440):634–40.

18. Guidelines Committee. 2013 European Society of Hypertension (ESH)/European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2013;31(7):1281–357.

19. Grosso A, Veglio F, Porta M, Grignolo FM, Wong TY. Hypertensive retinopathy revisited: some answers, more questions. Br J Ophthalmol 2005;89(12):1646–54.

20. Wong TY, Mitchell P. Hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med 2004;351(22):2310–7.

21. Wong TY, Mitchell P. The eye in hypertension. Lancet 2007;369(9559):425–35.

22. Sharma K, Kanaujia V, Mishra P, Agarwal R, Tripathi A.Hypertensive retinopathy. Clin Queries Nephrol 2013;2:136–9.

23. Handerson AD, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Hypertension-related eye abnormalities and the risk of stroke. Rev Neurol Di 2011;8(1–2):1–9.

24. Klein R, Sharrett AR, Klein BEK, Chambless LE, Cooper LS,Hubbardet LD, et al. Are retinal arteriolar abnormalities related to atherosclerosis? The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2000;20(6):1644–50.

25. Bock KD. Regression of retinal vascular changes by antihypertensive therapy. Hypertension 1984;6(6 Pt 2):III158–62.

26. Dahlof B, Stenkula S, Hansson L. Hypertensive retinal vascular changes: relationship to left ventricular hypertrophy and arteriolar changes before and after treatment. Blood Press 1992;1(1):35–44.

27. Department of Health. Report on population health survey 2003/04. Hong Kong SAR: Department of Health; 2005.

28. Centre for Health Protection, Hong Kong SAR [Internet]. Hypertension – the Preventable and Treatable Silent Killer. [accessed 2013 May 15]. Available from: www.chp.gov.hk.

29. Wolf-Marier K, Cooper RS, Kramer H, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S,Joffreset MR, et al. Hypertension treatment and control in five European countries, Canada, and the Unites States. Hypertension 2004;43(1):10–7.

Appendix

Lap-kin Chiang, MBChB(CUHK), MSc (CUHK), MFM(Monash)Family Medicine and General Outpatient Department,Kwong Wah Hospital, 1/F, Tsui Tsin Tong Outpatient Building,Kwong Wah Hospital, 25 Waterloo Road, Mongkok, Hong Kong, China

E-mail: chialk@ha.org.hk

14 March 2016;

Accepted 21 April 2016

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Corrigendum to "Sedentary lifestyle among adults in Jordan, 2007"[Family Medicine and Community Health 2016;4(3):4–8]

- Screening of intraocular pressure before routine pupil dilation for retinal photography: Clinical case report

- Healthy China 2030: "Without national health, there will be no comprehensive well-being"

- 'Feeling of despair' as the leading cluster theme of conceptual descriptive analyses in participatory assessment: Russia Oxfam GB case study

- Engaging black sub-Saharan African communities and their gatekeepers in HIV prevention programs: Challenges and strategies from England

- Patient-centered care in a multicultural world