Implications of crude oil pollution on natural regeneration of plant species in an oil-producing community in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria

U.D Chima · G. Vure

ORIGINAL PAPER

Implications of crude oil pollution on natural regeneration of plant species in an oil-producing community in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria

U.D Chima · G. Vure

Received: 2012-03-15; Accepted: 2013-05-21

? Northeast Forestry University and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014

The study evaluated the impact of crude oil pollution on natural regeneration of plant species in a major oil-producing community in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Three sites—unpolluted site (US), polluted and untreated site (PUS), and polluted and treated site (PTS)—were purposively chosen for the study. The seedling emergence method was used to evaluate soil seed banks in the various sites at two depths, 0 to 10 cm and 10 to 20 cm. Woody-plant species richness, abundance, and diversity were higher in the US seed bank than in the PUS and PTS seed banks. The highest number of non-woody plants was observed in the US, followed by the PTS, and then the PUS. Both species richness and diversity of non-woody plants were highest at the US, followed by the PUS, and lowest in the PTS. Woody species in the US seed bank were 87.5% and 80% dissimilar with those of the PUS and PTS at 0–10 cm and 10–20 cm respectively. No variation was observed between woody species in the PUS and PTS seed banks. Non-woody species at 0?10 cm US seed bank were 73.08% dissimilar with those of PUS at the two soil depths and 81.48/88.46% dissimilar with those of the 0–10/10–20 cm of the PTS respectively. At 10–20 cm, non-woody species of the US were 69.66% dissimilar with those from each of the two soil depths in PUS; and 73.91/81.82% dissimilar with those of 0–10/10–20 cm of the PTS respectively. Non-woody species variation between the PUS and PTS was higher at 10–20 cm than 0–10 cm. The poor seed bank attributes at the polluted sites demonstrates that crude oil pollution negatively affected the natural regeneration potential of the native flora because soil seed banks serve as the building blocks for plant succession. Thorough remediation and enrichment planting are recommended to support the recovery process of vegetation in the polluted areas.

Ogoni land, crude oil pollution, remediation, plant regeneration

Introduction

Contamination of soil by crude oil spills is a global environmental problem. Crude oil, the raw component of nearly all petroleum products, contains a wide variety of elements combined in various forms: the main components are carbon and hydrogen, which in their combined form are called hydrocarbons (ABB 1997). Shifts in the composition of the soil’s microbial community—as a response to low levels of gaseous hydrocarbons from underlying petroleum formations—have been investigated as support for further monitoring in case of accidental spills. Michel et al. (2002, 2005) state that petroleum is a pollutant that can persist in the environment for a long period until vegetation recovers completely; its persistence can be explained by the slow biodegradation of hydrocarbons.

The inhibition of germination and reduction of plant growth are indicators of the toxicity of hydrocarbons (Powell 1997). Oil contamination causes a slow rate of germination in plants (Ogbo et al. 2009), which has been attributed to the prevention or reduction of the seeds’ access to water and oxygen (Adam and Duncan, 2002). Cell membranes are damaged by penetration of hydrocarbon molecules, leading to leakage of cell contents. Oil reduces the transpiration rate, probably by blocking stomata and intercellular spaces (Baker 1970).

Coastal ecosystems in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria are under increasing pressure from hostilities and other developmental activities. The region has a long history of crude-oil pollution. Causes of oil spills in the area are usually accidental or operational. Accidental spills occur mainly due to equipment failure. Such spills have occurred at several times and places within the region (e.g., July 1970, April 2009, and April 2012, etc. at Bomu Oil Field in the Kegbara Dere Community). Operational spills occur due to loading and discharging oil from ships and illegal bunkering activities. These spills usually cause a lot of harm to the biological resources of the area.

Recovery of the area after spills will depend on thorough remediation or degradation of the oil and regeneration of the plantcommunities. Although the oil companies responsible for these spills in the Niger Delta sometimes carryout remediation activities, no studies have been conducted to either ascertain the impact of the spills on the regenerative potentials of the soil seed banks, or the effectiveness of the remediation effort, especially as it concerns regeneration of the native woody species of the area. Our study was a step in that direction: the specific objectives were: (1) to identify and compare the plant species composition of the soil seed banks in the unpolluted, polluted, and remediated sites; (2) to ascertain the impact of crude oil pollution on the viability and diversity of the soil seed bank; (3) to determine the effectiveness of the remediation carried out with respect to plant regeneration; and (4) to ascertain the impact of soil depth on the abundance of soil seed banks in the three sites considered.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area

Kegbara Dere is located in Gokana Local Government Area of Rivers State. It lies in the humid tropical zone with annual rainfall that ranges from 2000–2470 mm and an annual temperature ranging from 23°C minimum to 32°C maximum (NDES, 2001). The vegetation of the area is made up of an intricate mixture of plants that belong to different plant families, genera, and species. However, for the areas polluted with crude oil, the plants (mostly grasses) are in patches and are sparsely distributed on the site.

A report from Port Harcourt Appeals Court (1994) observed that the soils of the polluted areas of the community are resistant to penetration by plant roots; have high bulk densities, low hydraulic conductivities, and infiltration capacities; and consequently, very poor plant growth. The report also stated that soil samples from the polluted areas are very acidic, poor in total nitrogen, available phosphorous, and organic carbon, and generally have low levels of exchangeable cations and micronutrients, and high level of manganese, all toxic to plant life.

Selection of the study sites

Three sites were used for the study. The first site (4°39'8" N and 7°14'26" E) was selected from an unpolluted area (about 5 km away from the Kegbara Dere/Bomu Oil Field). The second site (4°39'37" N and 7°15'8" E) was selected from a polluted but treated or remediated area; while the third site (4°39'41" N and 7°15'6" E) was selected from a polluted and untreated area. The remediation carried out at the polluted/treated site involved manual tillage and bulking of soil; this was done in 2007 and 2008. These sites were chosen to ascertain the impact of crude oil pollution on the regenerative abilities of the sites and the effectiveness of the remediation exercises.

Studies on soil seed bank

Ten (10) random plots, 20 cm x 20 cm. were marked out at each site. Soil samples were removed from the 0–10 cm and 10–20 cm soil layers of each plot, using a sharp knife and hand trowel. Soil samples from corresponding soil layers were bulked for each site and divided into four equal parts. Germination trials were conducted for the different soil samples in the nursery. Soils were spread to a thickness of 3 cm on perforated plastic trays that were continuously kept moist. The seedling emergence method was used to assess the composition of the soil seed banks over a period of six months. Emerging seedlings that were readily identifiable were counted, recorded, and discarded on a monthly basis. Seedlings that were difficult to identify were counted, labeled, transplanted, and grown separately until they could be identified. After identification and counting of seedlings each month, the soil samples were stirred to stimulate seed germination.

Measurement of seedling diversity

The Simpson Diversity Index (Simpson, 1949) and Shannon Diversity Index (Odum, 1971) were used to measure diversity of the soil seed banks using Paleontological Statistics (PAST) software.

The Simpson Index is expressed as:

where: N is the total number of individuals encountered, ni is number of individuals of ith species enumerated for i=1……q, q is number of different species enumerated.

Shannon Diversity Index is expressed as:

where: pi is the proportion of individuals in the ith species, s is the total number of species.

Comparison of seed banks at different sites

The Sorensen Similarity Index was used to compare soil seedbank species composition between sites and soil depths. The index was computed using the methods found in Ogunleye et al. (2004), Ojo (2004), and Ihenyen et al. (2010), as expressed below:

where: a is the number of species present in both sites; b is the number of species present in site 1 but not present in site 2; c is the number of species present in site 2 but not present in site 1.

Results

Woody plant species composition of the various sites

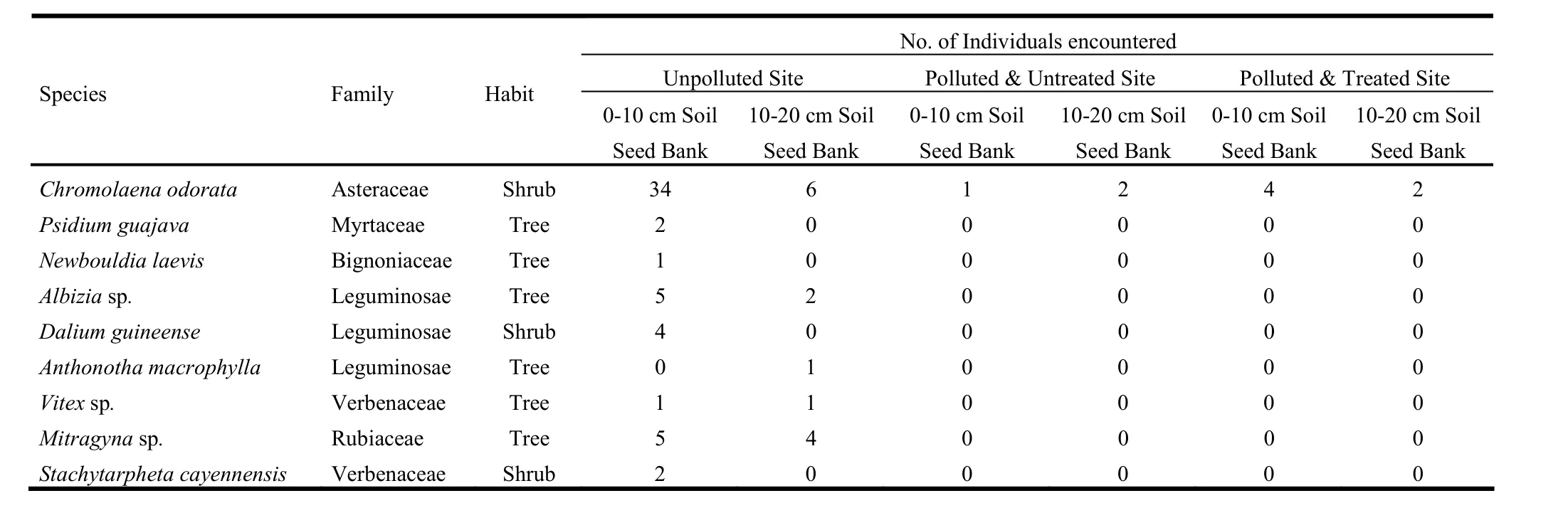

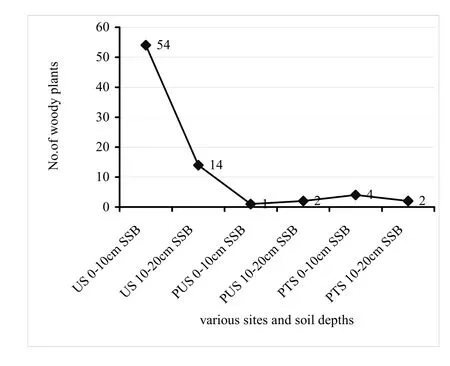

Table 1 shows the woody plant species that germinated from soil seed banks at various sites and soil depths. The abundance of woody plant species was greater in the seed bank of the unpolluted site than in the polluted/untreated site and polluted/treated site (Fig. 1). No woody tree species was recorded at both the polluted/untreated site and polluted/treated site (Fig. 2).

Non-woody plant species composition of the various sites

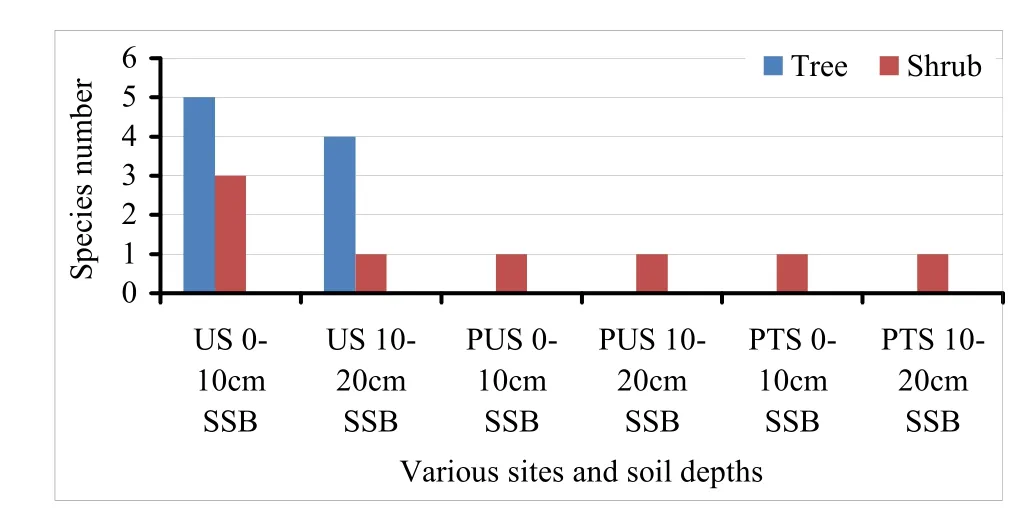

Table 2 shows the non-woody species recorded from the soil seed banks at various sites and soil depths. The highest number of non-woody plants was observed at 0–10 cm seed bank of the unpolluted site, followed by 0–10 cm soil seed bank of the polluted/ treated site, while the lowest number was observed at the 10–20 cm seed bank of the polluted/untreated site (Fig. 3). The abundance of non-woody plants decreased with the increase in soil depth in all the sites.

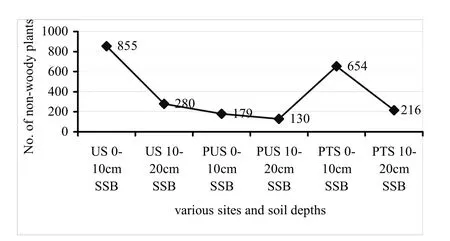

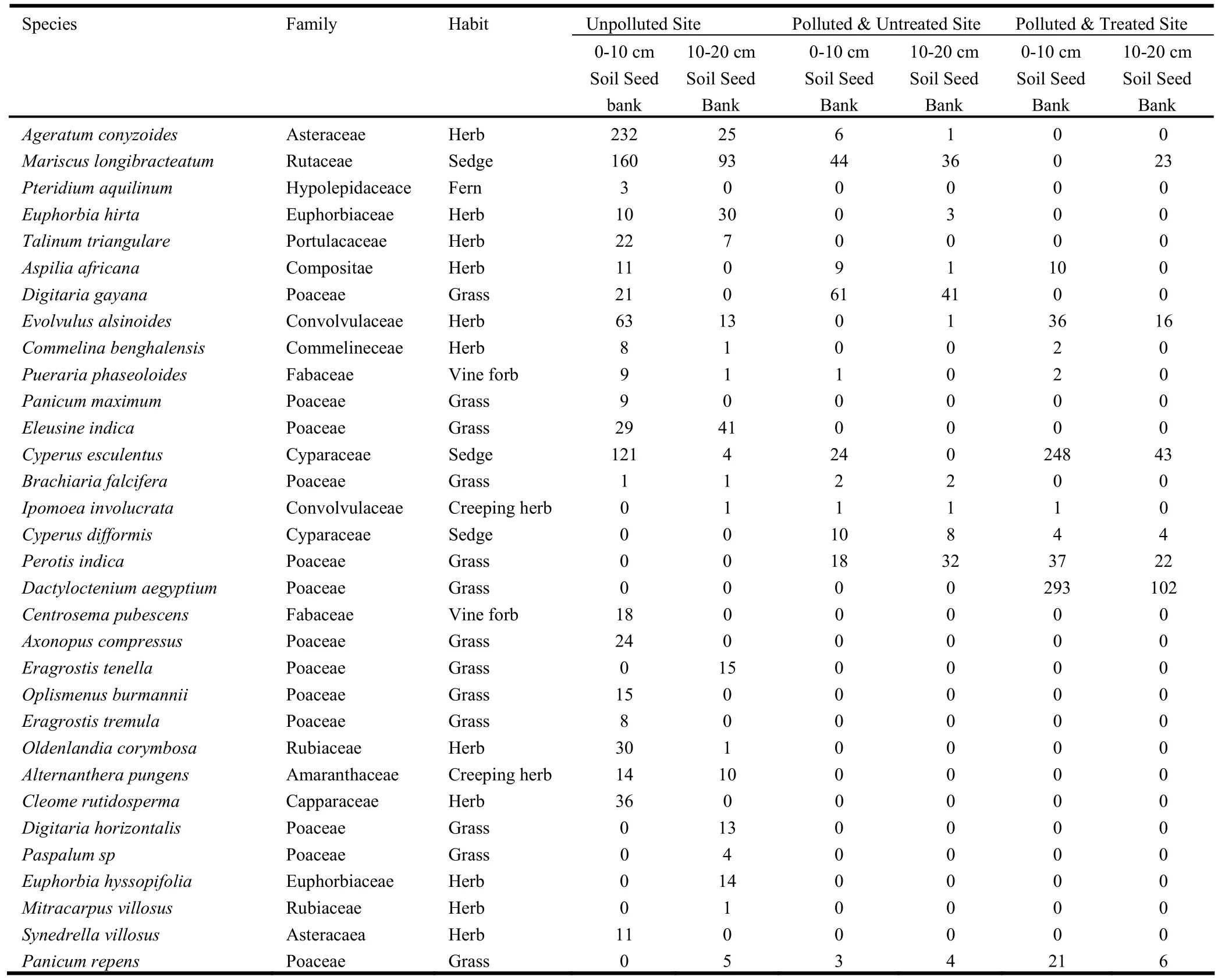

Table 1: Checklist of Woody Plant Species and Number of Individuals encountered in all the Sites

Fig. 1: Number of woody plants that germinated from soil seed banks at various sites and soil depths. US 0-10 cm SSB = Unpolluted Site 0-10 cm Soil Seed Bank; US 10-20 cm SSB = Unpolluted Site 10-20 cm Soil Seed Bank; PUS 0-10cm SSB = Polluted and Untreated Site 0-10 cm Soil Seed Bank; PUS 10-20 cm SSB = Polluted and Untreated Site 10-20 cm Soil Seed Bank; PTS 0-10 cm SSB = Polluted and Treated Site 0-10 cm Soil Seed Bank; PTS 10-20 cm SSB = Polluted and Treated Site 10-20 cm Soil Seed Bank. Same explanation for Figs 2-4.

Fig. 2: Distribution of germinated woody plant species among woody plant forms

Fig. 3: Number of non-woody plants that germinated from soil seed banks at various sites and soil depths

Table 2: Checklist of Non-Woody Plant Species and Number of Individuals encountered in all the Sites

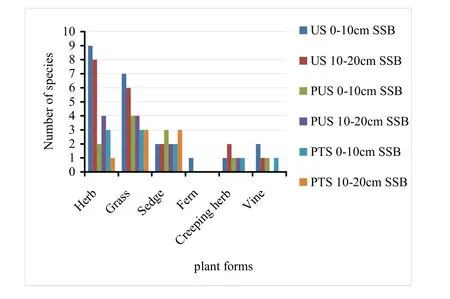

The distribution of germinated non-woody plant species among plant forms is shown in Fig. 4. The herbs and grasses were greater in the two soil depths of the unpolluted site than in both soil depths at the other sites. More sedge was found at 0–10 cm seed bank of the polluted/untreated site and 10–20 cm soil seed bank of the polluted/treated site. Creeping herbs were more in the 0–10 cm soil seed bank of the unpolluted site, while fern was recorded only at this site and soil depth.

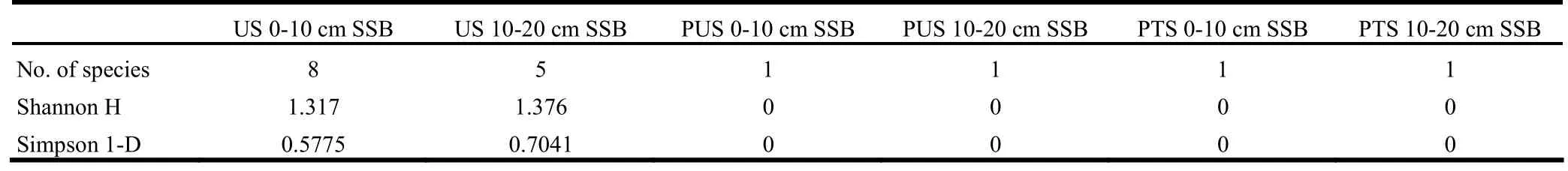

Diversity of woody plant seedlings at various sites/soil depths

The diversity of woody plant seedlings are shown in Table 3. The richness of woody plant species was greatest at the 0–10cm seed bank of the unpolluted site followed by the 10–20 cm seed bank of the same site while only one woody species was recorded at the two soil depths in both the polluted/untreated and polluted/treated sites. Woody plant species diversity was zero for both soil depths at the polluted/untreated and polluted/treated sites.

Fig. 4: Distribution of germinated non-woody plant species among plant forms

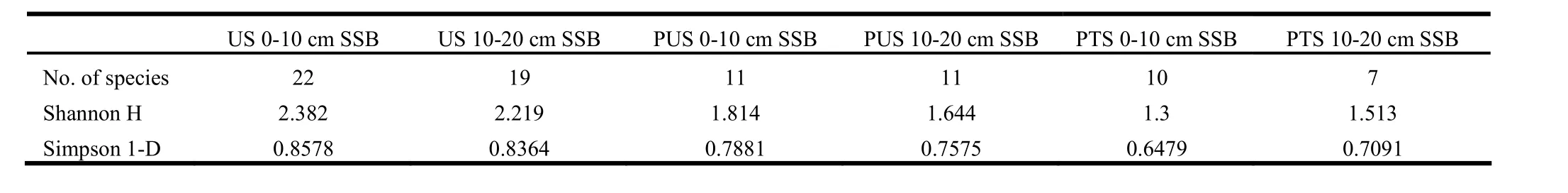

Diversity of the non-woody plant seedlings at various sites/soil depths

Table 4 presents diversity indices for non-woody plant species at various sites and soil depths. Both species richness and diversity were highest at the unpolluted site, followed by the polluted/untreated site while the polluted/treated site had the lowest species richness and diversity.The diversity of non-woody plant species decreased with soil depth except at the polluted/treated site.

Table 3: Alpha Diversity Indices for Woody Plant Seedlings

Table 4: Alpha Diversity Indices for Non-Woody Plant Seedlings

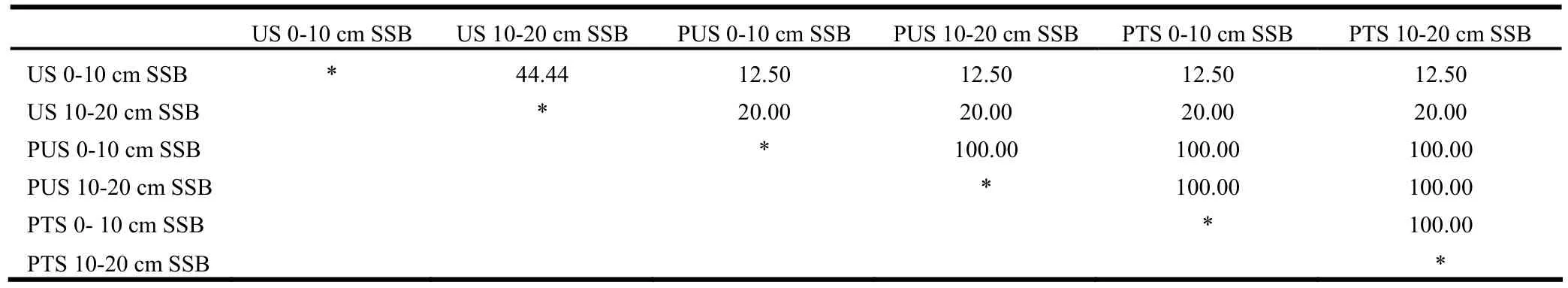

Plant species compositional variation among sites and soil depths The extent of plant species compositional variation between sites and soil depths is shown in Table 5 for woody species. Woody species in the seed bank at the unpolluted site were 87.5% and 80% dissimilar with those in the polluted/untreated and polluted/treated sites at 0–10 and 10–20 cm respectively. No variation was observed between woody species from seed banks in the polluted/untreated and polluted/treated sites.

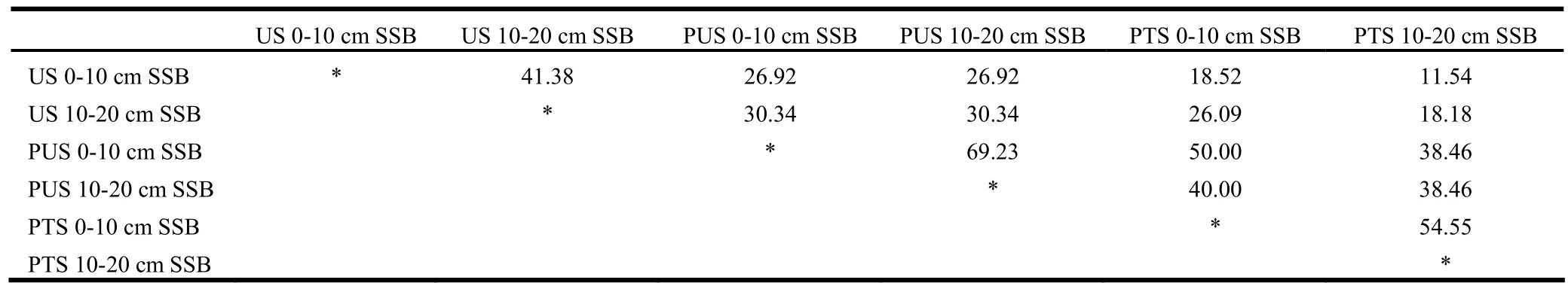

The level of variation in non-woody species composition was higher between the unpolluted site and the polluted/treated site than between the unpolluted site and the polluted/untreated site (Table 6). Non-woody species variation between the polluted/untreated site and polluted/treated site was higher at 10–20 cm than 0–10 cm.

Table 5: Sorensen’s Similarity Indices for seed bank woody seedlings

Table 6: Sorensen’s Similarity Indices for non-woody plants at the various sites

Discussion

The germination trials showed more plant species in the seed bank of the unpolluted site than that of either the polluted/untreated or polluted/treated sites. Although woody plant species were generally few in all of the sites compared with the non-woody species, the unpolluted site compared better than the polluted/untreated and polluted/treated sites where only one woody species, Chromolaena odorata, was observed. Nonwoody species dominated the soil seed banks in all sites, although the unpolluted site also demonstrated greater species richness and abundance than the other two. The polluted/untreated site had higher non-woody species richness than the polluted/treated site while non-woody plant abundance washigher in the polluted/treated site than in the polluted/untreated site.

Several studies on seed banks also show few woody species in comparison to non-woody species (Kebrom and Tesfaye 2000; Senbata and Teketay 2002; De Villiers et al 2003; Jalili et al. 2003; Wassie and Teketay 2006; Oke et al. 2007). Oke et al. (2007) observed that herbaceous species dominated the seed bank, consisting of 98% of the total seed density in each of the four plantations studied, with only three woody species emerging. The paucity of woody species in the seed bank of the unpolluted site may be attributed to the short-lived nature of their seeds. (Garwood 1989, Wassie and Teketay 2006). However, the higher species richness and seedling abundance recorded in the unpolluted site are indicative of the harmful impact of crude oil pollution. Although, there is no available literature on the effect of crude oil pollution on seed banks, Tefera et al. (2005) reported that disturbed lands had less seed density compared to adjacent undisturbed land. Powell (1997) equally asserted that the inhibition of germination and the reduction of plant growth, as well as death, are indicators of the toxicity of hydrocarbons in an oil polluted area.

Generally, seedling abundance decreased with soil depth in all of the sites with over 70% of non-woody seedlings encountered at the 0–10 cm seed bank of both the unpolluted and polluted/treated sites, and about 58% at the polluted/untreated site. Degreef (2002) observed that most seeds are located on the surface of the soil and that their numbers decline with depth.

Woody plant species diversity was zero at both the polluted/untreated and the polluted/treated sites. Crude oil pollution appears to have a greater impact on the diversity and density of the woody plant species than the non-woody species. This may be due to the advantages most non-woody species have in colonizing degraded sites with respect to the dispersal of their seeds. Because most woody species depend on seed rain for their regeneration due to the short-lived nature of their seeds, the destruction of mature trees due to crude oil pollution may have contributed to the very poor woody species richness, diversity, and abundance. However, higher non-woody seedling abundance in the polluted/treated site than in polluted/untreated site could be attributed to improved site conditions after remediation. Dereje et al. (2003) observed that biological and soil factors contribute to variations in species richness and diversity.

The high variation between the plant species composition in seed banks at the unpolluted site and the polluted sites could be due to the absence of toxic pollutants, and favorable biological andsoil conditions in the unpolluted site. It is well known that hydrocarbons are harmful to animals and plants (Dorn and Salanitro 2000). The inhibition of germination and the reduction of plant growth as well as its death, are indicators of the toxicity of hydrocarbons (Powell 1997). However, the existence of Chromolaena odorata in both the polluted/untreated and polluted/treated sites is indicative of its ability to colonize and thrive in degraded sites.

The poor seed bank attributes at the polluted sites demonstrate how crude oil pollution impairs on the natural regeneration potential of the native flora because the soil seed bank serves as a building block for plant succession. For example, the rapid revegetation of sites disturbed by wildfire, catastrophic weather, agricultural operations, and timber harvesting is largely due to the soil seed bank. A study into the natural process that influence forest dynamics has shown that soil seed bank is one of the principle sources of recruitment for new individuals in the initial stages of forest succession (Butler and Chazdon 1998). It also is partially responsible for dynamic changes that may occur during the development of vegetation (Lunt 1997). Williams-Linera (1993) equally observed that species richness and abundance in soil seed banks may provide information on the potential of a community for regeneration.

Conclusion

The soil seed bank of the unpolluted site compared better than those of the polluted/untreated and polluted/treated sites in terms of plant species richness and diversity, and seedling abundance. Plant species compositional variation was very high between the unpolluted site and the polluted sites. The remediation carried out in 2007 and 2008 seems not to have been very effective.

To restore the plant communities of the polluted areas, thorough remediation should be carried out by seasoned professionals who are committed to the project. . Since natural regeneration cannot guarantee the restoration of the plant communities (especially the woody species) at the polluted sites, enrichment planting using relevant silvicultural practices should be carried out to support and enhance the recovery process. This effort should involve collaboration with all of the stakeholders, including local people, government, oil companies, and professionals, like forest ecologists, soil scientists, and silviculturists.

ABB. 1997. ABB’s Environmental Management Report. ABB, Stockholm, 88pp.

Adam GI, Duncan H. 2002. Influence of diesel on seed germination. Environmental Pollution, 120: 363?370.

Baker JM 1970. The effects of oils on plants. Environmental Pollution, 1(1): 27?44

Butler BJ, Chazdon RL. 1998. Species richness, spatial variation and abundance of the soil seed bank of a secondary tropical rain forest. Biotropica 30: 214?222.

Degreef J, Rocha OJ, Vanderborght T, Baudoin J-P 2002. Soil seed bank and seed dormancy in wild populations of lima bean (Fabaceae); Considerations for in situ and ex situ conservation. American Journal of Botany, 89: 1644?1650.

Dereje A, Oba G, Weladji RB, Colman, JE. 2003. An assessment of restoration of biodiversity in degraded high mountain grazing land in northern Ethiopia. Land Degradation and Development, 14: 25?38.

De Villiers AJ, Van Rooyen, Theron GK. 2003. Similarity between the soil seed bank and the standing vegetation in the Strandveld Succulent Karoo, South Africa. Land degradation and Development, 14: 527?540.

Dorn PH, Salanitro J. 2000. Temporal ecology assessment of oil contaminated soils before and after bioremediation Chemosphere, 40(4): 419?426.

Garwood NC. 1989. Tropical soil seed bank, a review. In: Leck, M.A., Parker, V.T. and Simpson, R.L. (eds.), Ecology of Soil Seed Banks. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press, pp.149?209.

Ihenyen J, Mensah JK, Okoegwale EE. 2010. Tree/shrubs species diversity of Ehor Forest Reserve in Uhunmwode Local Government Area of Edo State, Nigeria. Researcher. 2(2): 37?49.

Jalili A, Hamzeh’ee Y, Asri A, Shirvany S, Yazdani, M, Khoshnevis F, Zarrinkamar M, Ghahramani R, Safavi S, Shaw J, Hodgson K, Thompson M, Akbarzadeh, Pakparvar. 2003. Soil seed bank in the Arasbaran protected area of Iran and their significance for conservation management. Biological Conservation, 109: 425?431.

Kebrom T, Tesfaye B. 2000. The role of seed banks in the rehabilitation of degraded hill slopes in Southern Wello. Biotropica, 32: 23?32.

Lunt ID. 1997. Germinable soil seed banks of anthropogenic native grasslands and grassy forest remnants in temperate south-Eastern Australia. Plant Ecology, 130: 21?34.

Michel J, Henry JR CB, Thumm S. 2002. Shoreline assessment and environmental impacts from the M/T Westchester Oil Spill in the Mississippi River. Spill Science & Technology Bulletin, 7(3-4): 155?161.

Michel J, Trevor G, Waldron J, Blocksisidge CT, Etkin DS, Urban R. 2005. Potentially polluting wrecks in marine waters. In: Annals of the 2005 International Oil Spill Conference, pp. 1-84. Maio 16, Miami.

NDES. 2001. Biological Environmental Research Report. RSUST, Port Harcourt. Volume 46. 251pp.

Odum EP. 1971. Fundamentals of Ecology. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadephia, 574pp.

Ogbo EM, Zibigha M, Odogu G. 2009. The effect of crude oil on growth of the weed (Paspalum crobiculatum L.) – phytoremediation potential of the plant, African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 3(9): 229?233.

Ogunleye AJ, Adeola AO, Ojo LO, Aduradola AM. 2004. Impact of farming activities on vegetation in Olokemeji Forest reserve, Nigeria, Global Nest, 6(2): 131?140.

Ojo LO 2004. The fate of a tropical rainforest in Nigeria: Abeku sector of Omo Forest Reserve, Global Nest, 6(2): 116?130.

Oke SO, Ayanwale TO, Isola OA. 2007. Soil seedbank in four contrasting plantations in Ile-Ife area of Southwestern Nigeria. Resource Journal of Botany, 2: 13?22.

Port Harcourt Appeal Court. 1994. Report of Case between SPDC Nigeria Limited (Appellant/Defendant) and the Kegbara Dere People (Respondents/Plaintiffs).

Powell R. 1997. The use of plants as “Field” biomonitors. In: Wang, W. Gorsuch, J. and Hughes, J. (eds.), Plants for Environmental Studies. Boca Raton: Lewis, pp. 47?61

Senbeta F, Taketay D. 2002. Soil seed banks in plantations and adjacent natural dry Afromontane forests of central and southern Ethiopia. Tropical Ecology, 43(2): 229?242.

Simpson EH. 1949. Measurement of diversity, Nature, 163: 688

Tefera M, Demel T, Hulten H, Yemshaw Y. 2005. The role of enclosures in the recovery of woody vegetation in degraded dryland hillsides of central and northern Ethiopia. Journal of Arid Environment, 60: 259?281.

Wassie A, Teketay D. 2006. Soil seed banks in church forests of northern Ethiopia: Implications for the conservation of woody plants. Flora, 201: 32?43.

Williams-Linera G. 1993. Soil seed bank in four low mountain forests of Mexico. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 9: 321?337.

DOI 10.1007/s11676-014-0538-y

The online version is available at http://www.springerlink.com

Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management, University of Port Harcourt- Choba, P.M.B. 5323, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. email: punditzum@yahoo.ca; phone: +234-803-812-1887

Corresponding editor: Chai Ruihai

Journal of Forestry Research2014年4期

Journal of Forestry Research2014年4期

- Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Growth and yield of two grain crops on sites former covered with eucalypt plantations in Koga Watershed, northwestern Ethiopia

- Full length cDNA cloning and expression analysis of annexinA2 gene from deer antler tissue

- Bamboo resources of Sikkim Himalaya: diversity, distribution and utilization

- Enhancement of seed germination in Macaranga peltata for use in tropical forest restoration

- Bio-amelioration of alkali soils through agroforestry systems in central Indo-Gangetic plains of India

- Spatial variability of soil organic carbon in the forestlands of northeast China