A modified Murashige and Skoog media for efficient multipleshoot induction in G. arborea Roxb.

Shilpa S. Madke · Konglanth J. Cherian · Rupesh S. Badere

Introduction

Gmelina arborea Roxb. of the family Verbenaceae is generally found scattered in mixed forests in moist regions and occasionally in evergreen forests of India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Philippines. It is a deciduous tree attaining the height of more than 30 m. G. arborea wood has many uses and construction is one of the most important. The properties of wood like high durability (Class I), termite resistance (Class II), high working quality index makes it the material of choice for making artificial limbs, matches, and making musical instruments. The plant has great medicinal value as well. The juice of tender leaves is demulcent and useful in treating gonorrhoea, catarrh of the bladder, and cough (Tewari 1995).

Woody perennials are among the essential components of the rural ecosystem since they cater to multipurpose needs (Pathak 1992). Recently, various government agencies and international organizations have also realized the potential benefits of multipurpose trees in the agroforestry system. It is, therefore, important to explore the MPTS (multipurpose trees and shrubs) germplasm to harvest its multidimensional benefits and their in situ and in vitro preservation (Mirza et al. 2008).

Cultivation of plants ensures genetically homogeneous stock in large number and therefore, seed propagation is not advisable as propagation of selected genotype through seeds is difficult. Although vegetative propagation through root suckers and cuttings guarantee genetic homogeneity, there are inherent limits like dependence on age and season. Such problems can be overcome by micropropagation because it ensures uniformity and scheduled year-round production of disease-free or pathogen-free plants (Kozai et al. 2000).

During the past few years, there has been great interest in propagating economically important tree species (Town et al. 2008). Various laboratories worldwide have attempted to employ in vitro techniques for propagation of ornamental and horticultural plant species. The in vitro production of plantlets of G. arborea has been reported by Chen et al. (1990), Kannan and Jasrai (1996), Sukartiningsih et al. (1999 and 2012), Naik et al. (2003), Behera et al. (2008) and Nakamura (2006).

Earlier attempts at micropropagation of tree species have been successful. Detailed protocols for other important species viz., Tectona grandis- a source of timber (Tiwari et al. 2002), Hevea brasiliensis- a source of natural rubber (Ighere et al. 2011), gum yielding trees like Sterculia urens (Town et al. 2008) and Acacia Senegal (Khalafalla and Daffalla 2008), and medicinal trees like Nothapodytes amamianus and Unacaria rhychophylla (Ishii et al. 2011) are available. Several factors play a role during organogenesis in plants: the most important are plant growth regulators (PGRs) and source of explants (Zulfiqar et al. 2009). Media constitution and genotype also decide the fate of explants over the media (Michel et al. 2008). Keeping this in mind, we designed a study to investigate the effect of PGRs, salts, carbon source, and explant source on multiple shoot induction in G. arborea.

Materials and Methods

Induction of microshoots

Seeds of G. arborea were purchased from the market and soaked in water for 24 hours before sowing in an autoclaved germination mixture (sand, coco-peat and vermicompost in 1:1:1 proportion) in a tray. The tray was kept at 90% relative humidity, 27 °C for a photo period of 16 hours. Seedlings of different ages (1, 2, and 3 weeks) were used to harvest explants like hypocotyl, cotyledonary leaf, epicotyl, true leaf, and shoot tip. Initially, the seedlings were washed with ExtranTM(Merck, Germany) for 30 min. Subsequently, the explants were harvested under asceptic conditions and surface sterilized, which was carried out by sequentially washing the explants with 0.1% HgCl2for 90 s and 70% ethanol for 60 s. The explants were washed with sterile distilled water between the two sterilents. The surface sterilized explants (50 each) were inoculated over agar-gelled MS medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962) containing, various concentrations of BAP, Kinetin, NAA (1-Naphthaleneacetic acid) and 2,4-D (2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) either alone or in combination. The cultures were maintained at 25±2 °C and a 16 hour photoperiod for four weeks (Table 1-3).

Rooting of shoots

Fifty microshoots, in each case, were cut when they attained the height of about 5 cm and then transferred to full-strength MS medium containing various concentration of IBA, NAA, IAA (3-Indoleacetic acid) and TCA (2,4,5-Trichloroacetic acid). The shoots were incubated under the same conditions as mentioned above for three weeks (Table 4).

Acclimatization

Fifty plantlets with well-developed roots were removed from the culture medium and washed gently with distilled water to remove the agar. Subsequently, the plantlets were planted into pots containing a sterile mixture consisting of sand, coco-peat, and vermi-compost in equal proportion and were covered with transparent polythene membrane to ensure high humidity. These plantlets were maintained at 25±2oC for a 16 hour photoperiod and irrigated with 1/8thstrength MS medium nutrient containing macronutrients, CaCl2and Fe-EDTA. After one month, the plantlets were transferred to bigger pots and kept in nursery under natural conditions for two months before being transplanted to the field.

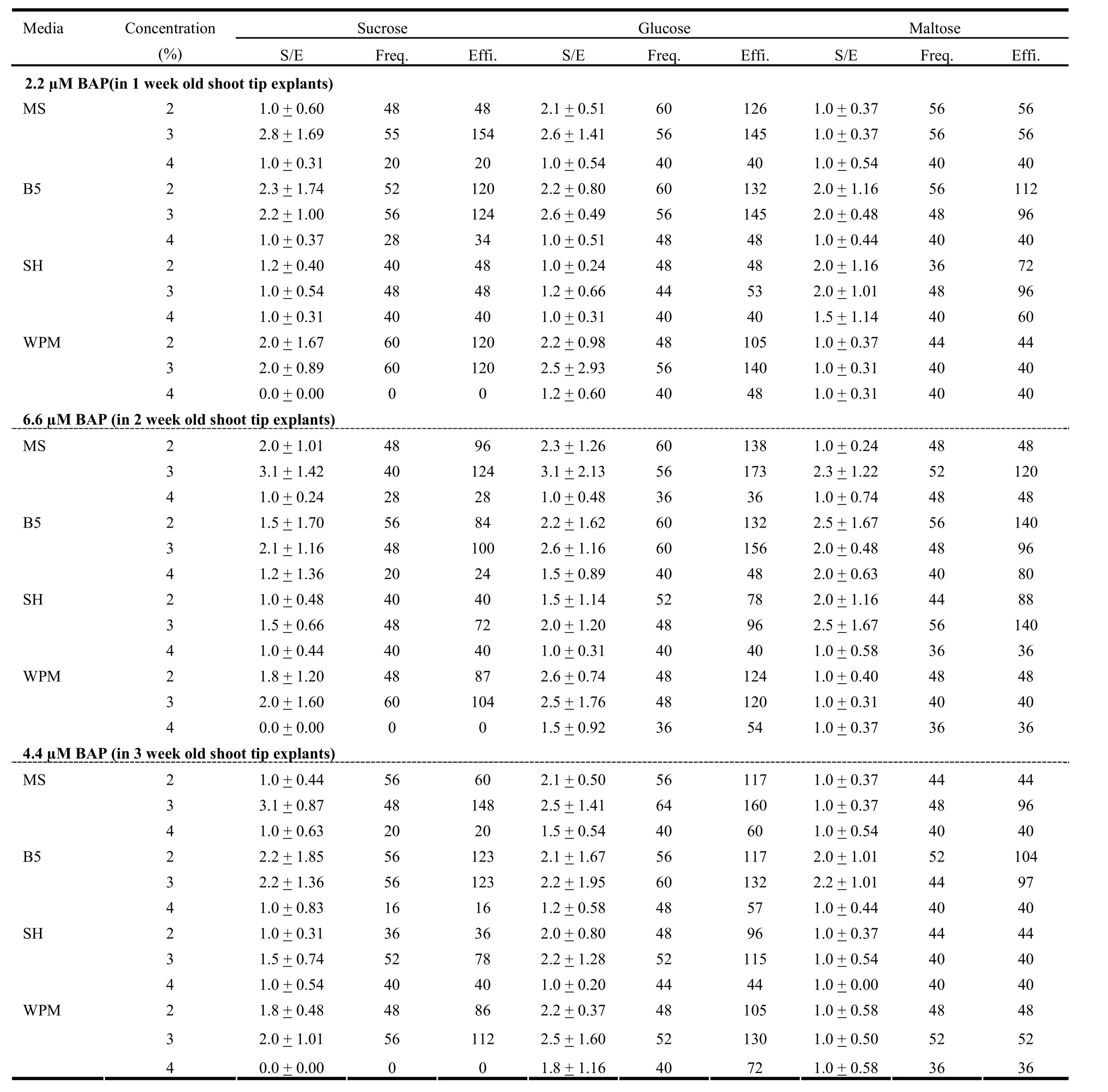

Effect of salt composition and carbon source on multiple shoot induction

Three different media viz., B5 (Gamborg et al. 1968), SH (Schenk and Hilderbrandt 1972) and WPM (Lloyd and McCown 1980) in addition to MS were used for this purpose. These media were fortified with different concentrations (2%, 3%, and 4%) of carbon sources like sucrose, glucose, and maltose. We selected the source and age of explants and the concentrations of PGRs, which performed well in the preliminary experiments. Next, 1, 2, and 3 week old shoot-tip explants (50 each) were inoculated over the media containing 2.2, 6.6 and 4.4 μM BAP, respectively. All of the combinations were supplemented with PGRs at a concentration that induced maximum multiple shoots in the preliminary experiments. The source and age of explants used in this study was the one that yielded multiple shoots in earlier attempts (Table 5 and Fig. 1 –3).

Statistical analysis

The results were statistically analysed, looking at mean, standard error, ANOVA, and Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) (p = 5%), using MS-Excel and XLSTAT (Table 6–8).

Results

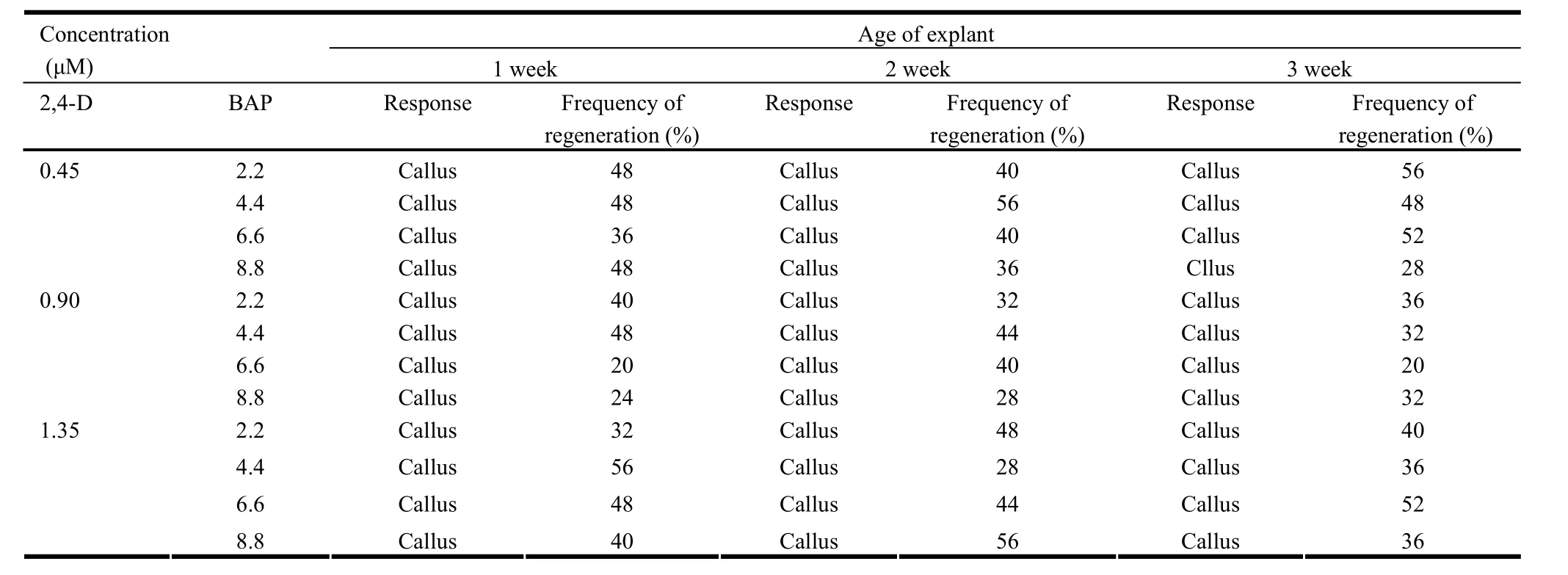

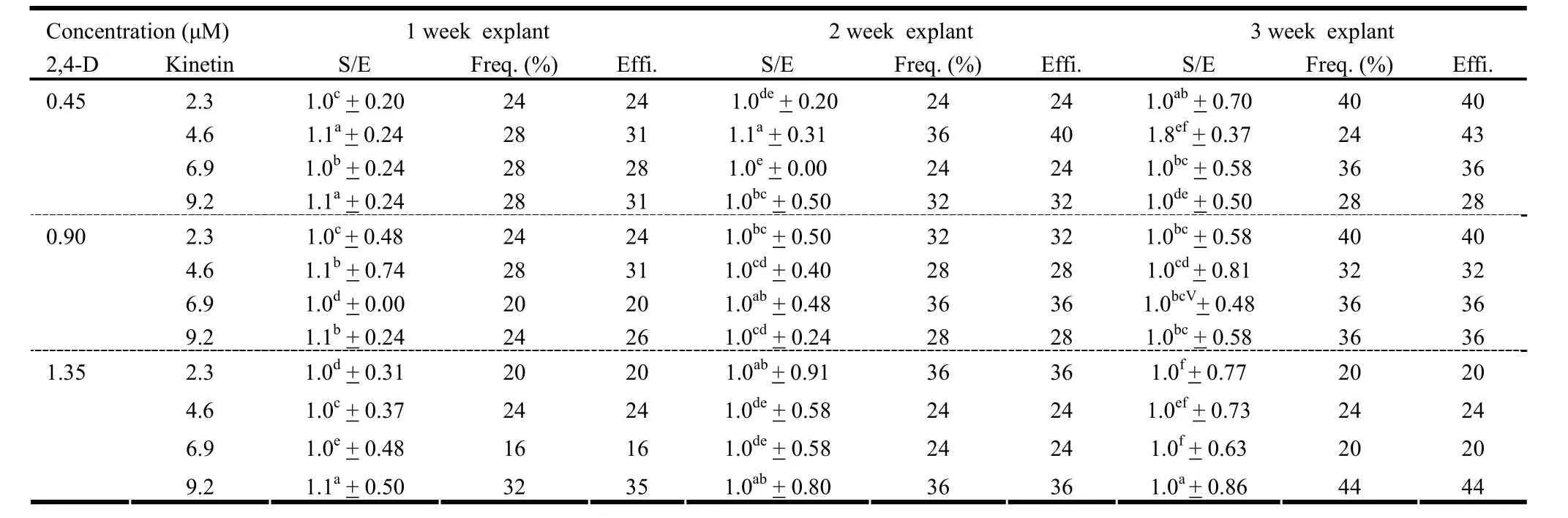

The response of explants varied according to the source, age of seedling and the PGR. Out of all the explants studied, only shoot tips formed microshoots in most cases. Besides, significant differences in the effect of PGRs on formation of microshoots were revealed by DMRT (Table 1-3). While the epicotyl and true leaf developed callus, cotyledonary leaf and hypocotyl showed no response in any of the cases (Data not given). BAP formed microshoots either alone or in combination with NAA (Table 1). However, in combination with 2,4-D, BAP formed calli with varying frequency (Table 2). In contrast to this, kinetin with NAA or 2,4-D formed microshoots but the frequency was too low (Table 1 and 3).

BAP alone was more efficient in inducing microshoots compared to in combination with NAA. Irrespective of the age of explants, number of shoots per explant, percent frequency of regeneration and thus, the regeneration efficiency, was noticeably high over the media containing BAP alone rather than in combination with NAA (Table 1). However, use of kinetin alone resulted in a slight increase in percent frequency of regeneration. On the other hand, no apparent effect of kinetin, alone or in combination with NAA or 2,4-D, was visible on number of shoots per explant (Table 1 and 3).

The regenerated shoots were transferred to full-strength MS medium for rooting. IBA, NAA, IAA and TCA at various concentrations were added to this media. In this case, the effect varied according to the PGR and its concentration. IBA was found to be the best auxin as its effect was not only early but the frequency was also high. In contrast, other PGRs had delayed less effect (Table 4). The regenerated plantlets were then acclimatized and hardened. After this, the plantlets were transferred to field conditions but the survival rate during this process was 56% (data not shown).

Table 1: Effect of BAP and NAA and Kinetin and NAA on multiple shoot induction in the shoot tip explants derived from seedlings of different age

Table 2: Effect of BAP and 2,4-D on multiple shoot induction in the shoot tip explants derived from seedlings of different age

Table 3: Effect of Kinetin and 2,4-D on multiple shoot induction in the shoot tip explants derived from seedlings of different age

Table 4: Effect of auxins on root induction in microshoots

Based on this preliminary study, we finalized the age of explants and concentration of PGR for further studies. We found BAP was the best PGR for inducing microshoots formation. Although the shoot tips of 1, 2, and 3 week old seedlings showed similar regeneration efficiency, the concentration of BAP at which such response was seen differed. For the 1, 2, and 3 weekold seedlings, maximum regeneration efficiency was found with 2.2, 6.6, and 4.4 μM BAP, respectively. Therefore, we conducted three different experiments each using explants of specific age and BAP concentration combination. Each experiment included four different media viz., MS, B5, SH and WPM and three different carbon sources viz., sucrose, glucose and maltose. These sugars were used at the concentration of 2, 3, and 4%.

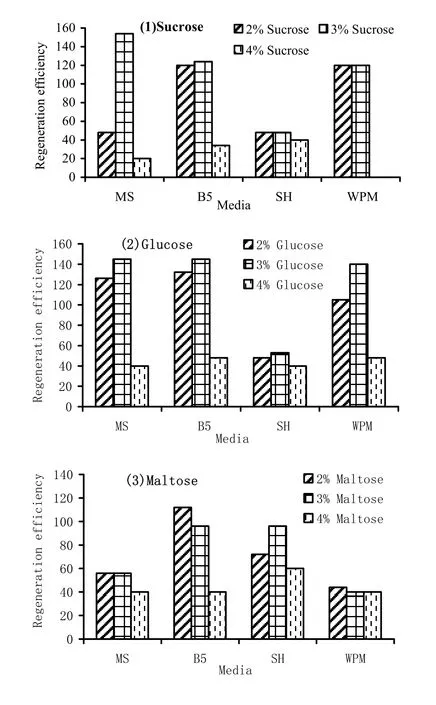

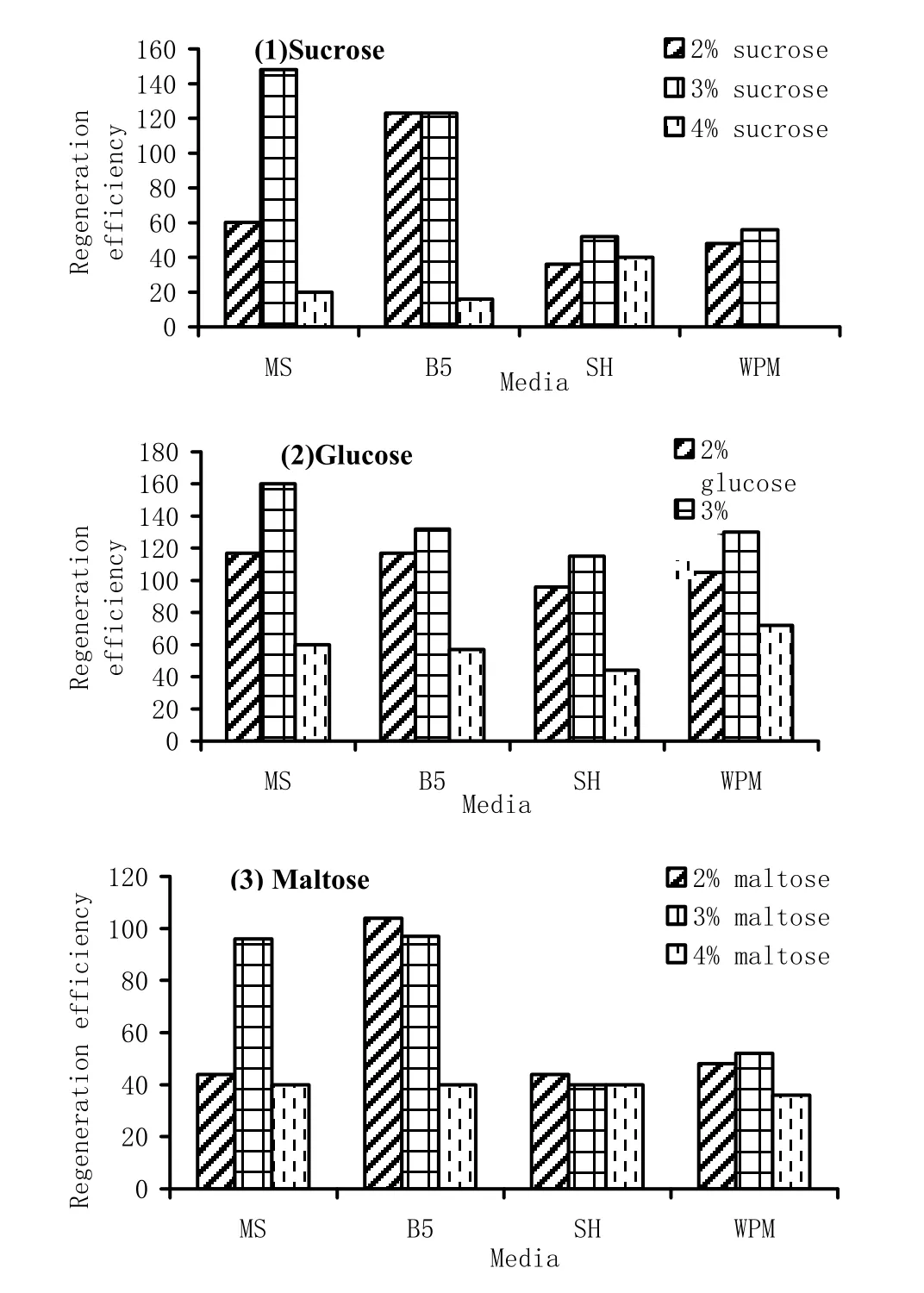

In the first experiment, the response of 1 week-old shoot tip explants over various media containing 2.2 μM BAP was studied. SH and WPM formed less shoots per explant compared to MS and B5 (Table 5). Besides, the frequency of shoot formation in SH and WPM also was less than MS and B5. Among all the three sugars used, maltose was least effective in inducing microshoots in terms of both shoot per explant and frequency. Sucrose and glucose had almost similar effect on these two aspects (Table 5).

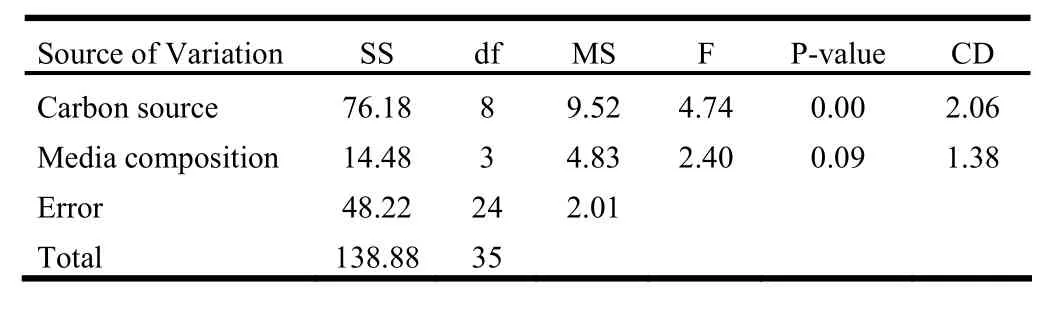

The overall effect of salts and sugars on regeneration was assessed in terms of regeneration efficiency. The two-way ANOVA revealed that sugar affected regeneration efficiency at the significance level of 1%. However, media composition had no significant effect. Apparently, all the sugars at 4% concentration drastically reduced the regeneration efficiency when compared to the 2 and 3% concentration (Table 6, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Regeneration efficiency of 1 week old explants over different media containing (1) sucrose, (2) glucose and (3) maltose and 2.2 μM BAP

Table 5: Effect of carbon source, its concentration and culture media along with 2.2, 6.6 and 4.4 μM BAP on multiple shoot induction in 1-week, 2-week, and 3-week old shoot tip explants

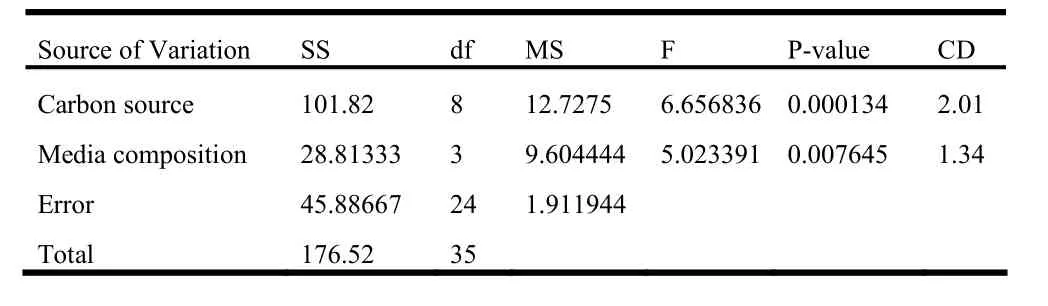

In the second experiment, 2 week-old shoot tip explants were inoculated over different media fortified with 6.6μM BAP. As far as shoots per explant and frequency are concerned, glucose was found to be the best sugar followed by sucrose and maltose. Among the media, MS had slightly more pronounced effect than B5, while SH and WPM had lower effect (Table 5). Regeneration efficiency was noticeably low with 4% of sugars compared to the other two concentrations in all the cases. In most cases the, efficiency was better with 3% sugars than with 2% sugars. Glucose was more effective in regeneration of shoots compared to sucrose and maltose. On the other hand, SH was the least effective media followed by WPM in most of the cases (Fig. 2). The two-way ANOVA test revealed that in this case the carbon source as well as media composition had significant effect (p =1%) over regeneration efficiency. Among sugars, the effect of 3% glucose differed significantly with 2% sucrose as well as maltose at all concentrations. Similarly, an important difference was also found between the effect of 2% glucose and 2% maltose. On the other hand, regeneration efficiency over B5 media was significantly different from SH and WPM (Table 7).

Table 6: Two-way ANOVA table for 1-week old shoot tip explant inoculated over media containing 2.2 μM BAP

Fig. 2: Regeneration efficiency of 2 week old explants over different media containing (1) sucrose, (2) glucose and (3) maltose and 6.6 μM BAP

Table 7: Two-way ANOVA table for 2 week old shoot tip explant inoculated over media containing 6.6 μM BAP

In the third experiment, 3 week-old shoot tip explants were inoculated over different media containing 4.4 μM BAP. The chemical nature of the sugar influenced the number of shoots per explant and regeneration frequency, which were maximum with glucose and minimum with maltose. Like in the earlier two cases, the shoot per explant and frequency were the minimum with 4% sugar in most of the cases (Table 5). The regeneration efficiency was the minimum with maltose in all the media studied. While in the case of sucrose and glucose, the effect on efficiency was almost equal with MS and SH media, but for SH and WPM, the efficiency was drastically reduced with sucrose (Fig. 3). As revealed by a two-way ANOVA, carbon source and media composition affected the regeneration efficiency significantly (p = 1%). A significant difference was found between various sugars and their concentration. Similarly, the effect of B5 was significantly different from MS, SH and WPM (Table 8).

Fig. 3: Regeneration efficiency of 3 week old explants over different media containing (1) sucrose, (2) glucose and (3) maltose and 4.4 μM BAP

Discussion

Mature explants have not worked as well in trees compared with herbaceous plants. This is because of factors like juvenility versus maturity, slow growth, infection and presence of phenolic compounds (Warrier et al. 2010). On the other hand, seedlingderived explants, because of their juvenility, are easily amenable to in vitro manipulation (Rathore et al. 2008). Being juvenile, active meristems are proportionately higher in seedlings, which could be stimulated for proliferation by using PGRs. Therefore, we have used only seedling-derived explants for the present study. Only shoot tip explants, among all tested, formed microshoots. This indicates the exclusive proliferation of axillary buds under the experimental conditions at least in this case. Nakamura (2006) has also reported the micropropagation of G. arborea through shoot tip explants. Similarly, Chen et al. (1990), Kannan and Jasrai (1996) and Behera et al. (2008) have also reported the proliferation of axillary buds under influence of BAP and TDZ (Thidiazuron) in G. arborea under in vitro conditions. Sukartiningsih et al. (2012) have exploited such proliferation of axillary buds in producing artificial seeds.

However, in contrast to this and our finding, Sukartiningsih et al. (1999) reported the induction of adventitious shoots in nodal explants of G. arborea by BAP, zeatin and TDZ. Although both the cytokinins used, BAP and kinetin, were successful in inducing microshoots, BAP was significantly better than kinetin. High cytokinin to auxin ratio seemed to be essential for higher regeneration efficiency when both cytokinins were used. But BAP alone was better for higher regeneration efficiency in G. arborea. Similar observations are reported by Rathore et al. (2008) in Terminalia bellarica, Rehman et al. (2004a) in F. benghalensis, and Khalafalla and Dafalla (2008) in A. senegal.

In the present study, although explants of all the age responded best with BAP alone, the concentration was different for each age. While for 1 week-old seedlings 2.2 μM BAP was best, for 2 and 3 week-old explants, the best BAP concentrations were 6.6 and 4.4 μM, respectively. The response of explants over the media is a combined effect of endogenous levels of PGRs in the tissue and PGRs supplied exogenously (Badere et al. 2002).

The highest rooting frequency was induced in microshoots by IBA. Similar observations have been made by Amin et al. (2005) in Annona squamosa, Rehman et al. (2004a, b) in Elaeocarpus robustus and F. benghalensis and Rathore et al. (2008) in T. bellarica.

Composition of media in terms of salts and their concentration also affects organogenesis and several media have been designed for this purpose. Therefore, an attempt was made to study the effect of various media on formation of microshoots. In all cases, MS was the best media for shoot induction, followed closely by B5. SH and WPM, on the other hand, had poor influence on shoot induction, particularly WPM. Notably, it is a low-salt medium with poor content of nitrogen, which is an important element in plant nutrition. WPM is also lower in potassium and chloride content. In addition it is high in copper which may be toxic to the soft tissues.

SH is a high-salt medium, it is poor in sulphur and iron, which play an important role in plant metabolism. MS and B5 are also high-salt media with mostly similar elements and therefore gave the similar responses. A similar study carried out on pomegranates by El-Agamy et al. (2009), reported WPM to be the better medium than MS and NN with respect to plantlet height, leaves per shoot, nodes per shoot, and length of internode.

Carbon is an important element in all living organisms as it forms the backbone of organic molecules. In plant tissue culture, sugar is the main carbon source for growing explants. In the present investigation, sucrose, glucose and maltose were tested for their efficacy on shoot induction. In all cases, the explants performed poorly over maltose. Although sucrose and glucose gave similar results but, mostly glucose proved to be better than sucrose. This was evident by the higher regeneration frequency with glucose as compared to that with sucrose in most of the cases. In addition to various carbon sources, different concentrations of sugars were also tested for their influence on regeneration in G. arborea.

All sugars at 4% concentration affected regeneration adversely. Being osmotically active, higher concentration of sugars must have increased the water potential of media, which affected the explants adversely. At 2% concentration, albeit, the effect of sugars on regeneration was better; but it was still lower than at 3%. In this case, the lower concentration might have limited the supply of adequate carbon to the growing explants. The superiority of glucose over other sources of carbon in regeneration has been known in other cases like in rice (Thapa et al. 2007), Gossypium hirsutum (Ganesan and Jayabalan 2005) and bitter almond (Rayya et al. 2010).

Glucose, being the preferred sugar for oxidative phosphorylation, seems to have performed well. Sucrose, on the other hand, serves as temporary reserve of carbon and is preferred for translocation in plants. Therefore, it seems obvious that it affected regeneration in a similar way to glucose. The presence of assimilable sugar affects regeneration efficiency by influencing the action of cytokinin, which controls cell division and the use of nitrate and ammonium ions, which are necessary for growth .

Conclusion

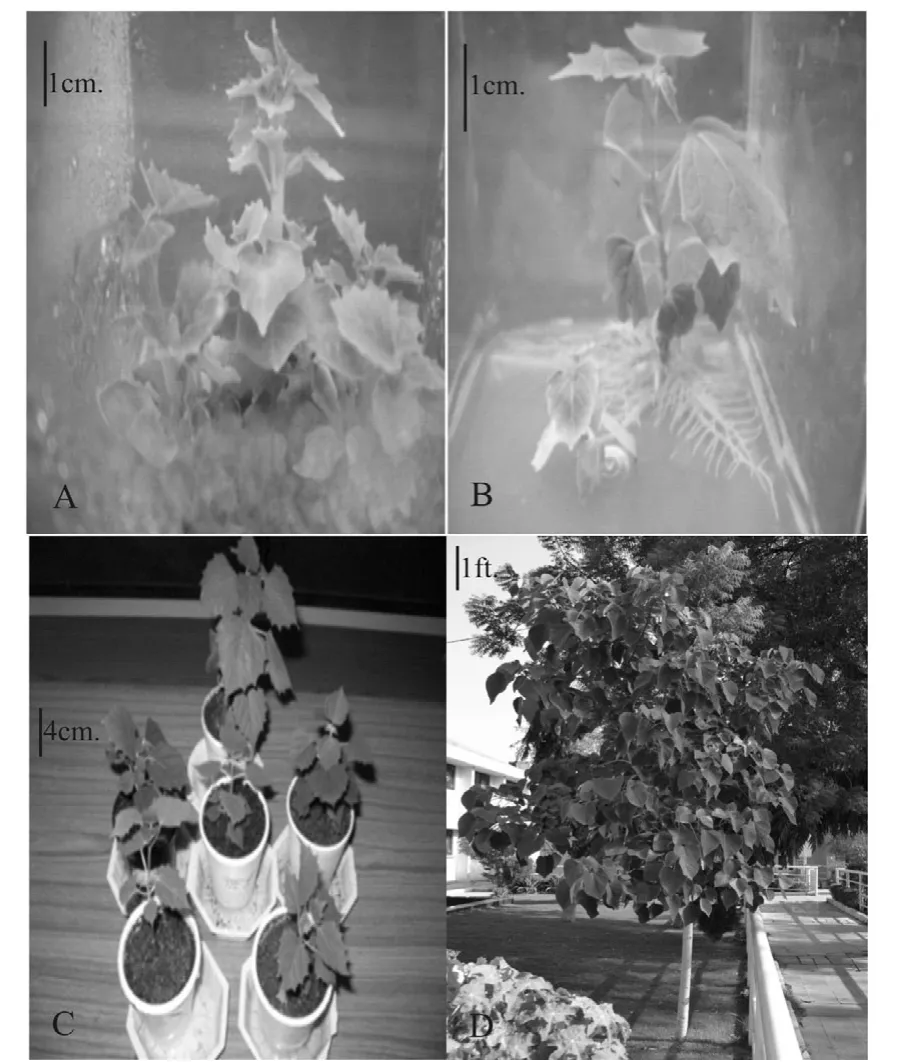

Based on our current research, we recommend the use of modified MS media in which 3% sucrose is replaced by 3% glucose and fortified with 6.6 μM BAP for micropropagation of G. arborea using 2 week-old shoot tip explants. Similarly, we recommend the use of 14.7μM IBA with MS medium of for rooting the microshoots (Fig. 4).

Acknowledgements:

The authors are grateful to Dr. V. Joglekar and Dr. J. Shivalkar, Department of Statistics, Hislop College, Nagpur, for their help in statistical analysis of the data.

Fig. 4. Regeneration of Gmelina arborea Roxb. A- Induction of multiple shoots (The 2 week-old shoot tip explants were inoculated over MS salts supplemented with 3% glucose and 6.6 μM BAP), B- Rooting of microshoots (Microshoots were inoculated over MS medium containing 14.7 μM IBA), CHardening of regenerated plantlets, D- Regenerated tree growing in field (All the in vitro manipulations were done at 25±2 °C and 16 hour photoperiod).

Amin MN, Rahman MM, Rahman KW, Ahmed R, Hossain MS, Ahmed MB. 2005. Large scale plant regeneration in vitro from leaf derived callus cultures of pineapple (Anannas comosus(L.) Merr.) cv. Giant Kew. Int J Botany, 1: 128-132.

Badere RS, Koche DK, Pawar SE, Choudhary AD. 2002. Regeneration through multiple shooting in Vigna radiata. J Cytol Genet, 3: 185-190.

Behera PR, Nayak P, Thirunavoukkarasu M, Sahoo S. 2008. Plant regeneration of Gmelina arborea Roxb. from cotyledonary node explants. Indian J Plant Physiol, 13(3): 258-265.

Chen Z, Evans DA, Sharp WR, Ammirato PV, Sondani MR.1990. Tissue culture of shoot apex from Moulay bushbeech (Gmelina arborea). In: Ammirato P.V., Evans D.A., Sharp W.R., Bajaj Y.P.S. (Eds.), Handbook of plant cell culture, New YorK: McGraw Hill Publishing Company, p. 37.

EI-Agamy SZ, Mostafa RAA, Shaaban MM, EI-Mahdy MT. 2009. In vitro propagation of Manfalouty and Nab EI-gamal pomegranate cultivars. Res J of Agric and Biol Sci, 5: 1169-1175.

Gamborg OL, Miller RA, Ojima K. 1968. Nutrient requirement of suspension cultures of soyabean root cells. Exp Cell Res, 50: 151-158.

Ganesan M, Jayabalan N, 2005. In vitro plant regeneration from the callus of shoot tips in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. cv. SVPR 2). Iranian J Biotech, 3: 144-150.

Ighere DA, Okere A, Elizabeth J, Mary O, Olatunde F, Abiodun S. 2011. In vitro culture of Hevea braziliensis (Rubber tree) embryo. Journal of Plant Breeding and Crop Science, 3: 185-189.

Ishii K, Takata N, Kurita M, Taniguchi T. 2011. Tissue culture of two medicinal trees native to Japan. IUFRO Tree Biotechnology Conference 2011: From Genomes to Integration and Delivery. Arraial d'Ajuda, Bahia, Brazil. BMC Proceedings, 5(supll.7): 137.

Kannan VR, Jasrai YT 1996. Micropropagation of Gmelina arborea. Plant cell Tiss and Org Cult, 46: 269-271.

Khalafalla MM, Daffalla HM 2008. In vitro micropropagation and micrografting of gum arabic tree (Acacia senegal (L.) Wild). Int J Sustain Crop Prod, 3: 19-27.

Kozai T, Kubota C, Zobayed Q, Afreen-Zobayed F, Heo J, 2000. Developing a Mass Propagation System for Woody plants. In: Proceedings of 12thToyata Conference: Challenge of Plant and Agricultural Sciences to the crisis of Biosphere on the earth in the 21st Century.

Lloyd G, McCown B 1980. Commercially feasible micropropagation of mountain laurel Kalmia latifolia by use of shoot tip culture. Proc. Int. Conf. Plant Prop. Soc., pp. 421-427.

Michel Z, Hilaire KT, Mongomake K, Georges AN, Justin KY. 2008. Effect of genotype, explants, growth regulators and sugars on callus induction in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Aust J Crop Sci, 2: 1-9.

Mirza B, Baig Ahmad S, Khan N, Khurshid M. 2008. Germplasm conservation of multipurpose trees and their role in Agroforestry for sustainable agriculture production in Pakistan. Int J Agri Biol, 10: 340-348.

Murashige T, Skoog F. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassay with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant, 15: 473-497.

Naik D, Vartak V, Bhargav S. 2003. Provenance- and Subculture-dependent variation during micropropagation of Gmelina arborea. Plant Cell Tiss Org, 73: 189-195.

Nakamura K. 2006. Micropropagation of Shorea roxburghii and Gmelina arborea. In: K. Sizuki, K. Ishii, S. Sakurai, and Sasaki, S. (Eds.), Plantation technology in tropical forest Science. Japan: Springer, pp. 137-150.

Pathak PS. 1992. Multipurpose trees and shrubs for agroforestry system. In: Jha, L.K. and Sharma, P.K.S. (Eds.), Agroforestry- Indian Perspective. New Delhi: Ashish Publishing House, pp. 31-59.

Rathore P, Suthar R, Purohit SD 2008. Micropropagation of Terminalia bellerica Roxb. from juvenile explants. Indian J Biotech, 7: 246-249.

Rayya AMS, Kassim NE, Ali EAM. 2010. Effect of different cytikinins concentrations and carbon sources on shoot proliferation of bitter almond nodal cuttings. J Ameri Sci, 6: 465-469.

Rehman MM, Amin MN, Hossain MF. 2004a. In vitro propagation of Banyan tree (Ficus benghalensis L.) - A multipurpose and keystone species of Bangladesh. Plant Tissue Cult, 12: 135-142.

Rehman MM, Aminm MN, Ahmed R, Azad MAK, Begum F, 2004b. In vitro plantlet regeneration from internode explant of native Olive (Elaeocarpus robustus roxb.). J Biol Sci, 4: 676-680.

Schenk RV, Hilderbrandt AC. 1972. Medium and techniques for induction and growth of monocotyledonous and dicotyledons plant cultures. Can J Bot, 50: 199-204.

Sukartiningsih, Nakamura K, Ide Y. 1999. Clonal propagation of Gmelina arborea Roxb. by in vitro culture. J For Res, 4: 47-51.

Sukartiningsih, Saito Y, Ide Y. 2012. Encapsulation of axillary buds of Gmelina arborea and Peronema canescens Jack. Bull Univ of Tokya For, 127: 57-65.

Tewari DN. 1995. A monograph on Gamari (Gmelina arborea Roxb.). Dehradun: International Book distributors.

Thapa R, Dhakal D, Gauchan DP. 2007. Effect of different sugars on shoot induction in rice cv. Basmati. Kathmandu Uni J Sci Engg and Tech, 1: 1-4

Tiwari SK, Tiwari KP, Siril EA. 2002. An improved micropropagation protocol for teak. Plant Cell Tiss Org, 71: 1-6.

Town MH, Thummala C, Ghanta RG. 2008. Micropropagation of Sterculia urens Roxb., an endangered tree species from intact seedlings. African Journal of Biotechnology, 7: 095-101.

Warrier R, Viji J, Priyadharshini P. 2010. In vitro propagation of Aegle marmelos L. (Corr.) from mature trees through enhanced axilliary branching. Asian J Exp Biol Sci, 1: 669-676.

Zulfiqar B, Abbasi NA, Ahmad T, Hafiz IA. 2009. Effect of explant sources and different concentrations of plant growth regulators on in vitro shoot proliferation and rooting of Avocado (Persea americana MILL.) cv. 'Fuerte'. Pak J Bot, 41: 2333-2346.

Journal of Forestry Research2014年3期

Journal of Forestry Research2014年3期

- Journal of Forestry Research的其它文章

- Effects of shifting cultivation on biological and biochemical characteristics of soil microorganisms in Khagrachari hill district, Bangladesh

- An integrated method for matching forest machinery and a weight-value adjustment

- Finite element analysis of stress and strain distributions in mortise and loose tenon furniture joints

- The in fl uence of silane coupling agent and poplar particles on the wettability, surface roughness, and hardness of UF-bonded wheat straw (Triticum aestivum L.)/poplar wood particleboard

- Genetic variation and selection of introduced provenances of Siberian Pine (Pinus sibirica) in frigid regions of the Greater Xing’an Range, Northeast China

- Characterization of expressed genes in the establishment of arbuscular mycorrhiza between Amorpha fruticosa and Glomus mosseae