The ‘physical-mental’ treatment of cardiovascular disease co-morbid with mental disorders

Yanping Ren, Hui Yang, Colette Browning, Shane Thomas

The ‘physical-mental’ treatment of cardiovascular disease co-morbid with mental disorders

Yanping Ren1, Hui Yang2, Colette Browning2, Shane Thomas2

A 47-year-old woman complained of sudden chest tightness, shortness of breath, palpitations and a severe headache. Her highest blood pressure had reached 200/120 mmHg before and was diagnosed as hypertension. One month ago, the results of her cranial CT scan showed multiple lacunar cerebral infarctions. She then complained of insomnia, extreme fatigue, poor appetite, loss of interest in everything and paid more attention to her blood pressure and measured blood pressure over five times per day at home. The patient went to visit a psychologist who drew the conclusion of depression. She took sertraline (50 mg once a day) and followed up with the psychologist in the following 2 weeks. During the last month, she has taken 30-mg nifedipine controlledrelease tablets once a day and the blood pressure was well-controlled. More attention should be paid to the mental status of patients with cardiovascular disease. There are many screening tools to assess depression in cardiovascular disease patients. The ‘physical-mental’ treatment of cardiovascular disease cannot be conducted at one time and follow-ups are necessary.

Hypertension, mental disorder, physical-mental, treatment

Introduction

Hypertension is the most common risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and is recognized as a global, chronic, non-communicable disease, and as a ‘silent killer’ because of its high mortality and lack of early symptoms [1]. One-quarter of the world’s adult population has hypertension, and the prevalence is likely to increase to 29% by 2025 [2]. A systematic review of the prevalence of hypertension in Chinese cities published in early 2013 showed a pooled prevalence of 21.5% [3], which was higher than the Chinese national average of 18% [4]. A recent study estimated that approximately 173 million Chinese, or nearly one in five adults, have a mental disorder, including depression, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)-IV [5]. The association between depression and hypertension has been increasingly reported. Depression is also the most important risk factor for hypertension [6]. Clinicians should therefore consider the mental status of the patient in the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of hypertension. In this case study, the author discusses the model of ‘physical-mental’management in hypertension co-morbid with depression.

History

The patient was a 47-year-old woman and mother of a university student. She had been a school teacher for 20 years. She visited the hospital emergency department accompaniedby her husband. She complained of sudden chest tightness, shortness of breath, and palpitations. Before leaving home, she measured her blood pressure, which was 180/100 mmHg. She had taken a 30-mg nifedipine controlled-release tablet (Baixintong), as prescribed by her physician at her last visit. Ten minutes later, her blood pressure increased to 190/110 mmHg. She lay down, rested for 10 min, and measured the blood pressure again. The blood pressure was now 200/110 mmHg. She also complained of a severe headache.

She was diagnosed with hypertension 1 year ago at X Hospital. Her blood pressure was 200/120 mmHg. She then sought evaluation at a number of hospitals and secondary hypertension was ruled out. She was informed of the possibility of target organ damage to the heart, kidneys, and fundi. The diagnosis was grade 3 hypertension (high risk). Although her treatment plan was adjusted after visiting different hospitals, her blood pressure still fluctuated. Because of her headache and fluctuating blood pressure, she sought evaluation at a hospital recommended by an acquaintance 1 month ago. The results of a cranial computed tomography (CT) scan showed multiple lacunar cerebral infarctions. She unintentionally heard the physician say “You are too young to suffer cerebral infarction” after she received the results of the brain CT 1 month ago. This comment made the patient more anxious. As a result, her emotions changed. She always complained of poor sleep, extreme fatigue, a lack of appetite, a loss of interest in everything, except paying more attention to her blood pressure and measuring her blood pressure >5 times per day at home. Of note, she had more fluctuations in blood pressure.

She had experienced irregular menstruation for nearly 1 year. Her father died of hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 48 years. Her mother, who was 76 years of age, was healthy. Her elderly brother had a history of hypertension. Her husband was healthy and they had a good marital relationship. The couple had a daughter, who was a student at a music college.

The physical examination showed painful anxiety, with her hands clenched to her husband. Her temperature was 36.4°C, her pulse was 92 beats/min, her respiratory rate was 28 breaths/min, and her blood pressure was 190/120 mmHg. There were no other positive findings.

Questions

1. What is the preliminary diagnosis? What are the reasons for the uncontrolled and fluctuating blood pressure?

2. How should patients with cardiovascular disease be screened for mental disorders?

Answers

1. The diagnosis of grade 3 hypertension was clear, according to the definition of the 2010 China guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension; specifically, values ≥140 mmHg systolic blood pressure (SBP) and/or ≥90 mmHg diastolic blood pressure (DBP) three times on different days and use of antihypertensive medicines meet the diagnostic criteria for hypertension. grade 3 hypertension is considered high risk because of the blood pressure level and combined cardiovascular risks; however, the diagnosis of grade 3 hypertension cannot explain all of the patient’s symptoms. There should be another diagnosis for the patient’s mental status. After assessing this patient, we found that there were other possible explanations for her unstable blood pressure. The patient was a 47-year-old woman, who was menopausal. Mood during the menopause is unstable and prone to be affected by external factors. The patient’s father died of cerebral hemorrhage at 48 years of age. She did not understand the relationship between hypertension and cerebral hemorrhage and thought she would follow her father. Hence, she had been treated for anxiety for a long time. Moreover, there may have been some iatrogenic effect of the physician’s comment (“You are too young to suffer cerebral infarction.”). The term (iatros=healer, curer) was introduced in 1951 by the german psychiatrist Oswald Bumke, who restricted the definition to mental disorders induced by negative mental influences by a physician.

Considering the above reasons and the complaints of extreme fatigue, poor sleep, lack of appetite, lack of confidence, and anhedonia for 1 month, depression is a likely diagnosis.

2. Screening for mental disorders in patients with cardiovascular disease is not the same as screening for simple mental disorders. The special situation of heart disease should be considered and a simple, practical, and easy screening tool is needed. There are many screening tools for assessing depression in cardiovascular disease patients,such as the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the geriatric Depression Scale (gDS) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2 and PHQ-9). There are no consistent screening tools recommended in different countries. PHQ-9 is a self-administered and easily-scored measure of depressive symptoms comprising 9 items that map onto the DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) [7]. PHQ-9 is commonly used to assess depressive symptoms among patients in medical settings, including patients with coronary artery disease [8]. The American Heart Association (AHA) Science Advisory recommends PHQ-9 for use in routine depression screening among patients with coronary heart disease in clinical settings. Figure 1 shows the flow chart used to screen for depression [9]. Tables 1 and 2 show the items on PHQ-2 and PHQ-9, respectively. The current patient responded ‘yes’ to two questions on PHQ-2, and the score on PHQ-9 was 18, which met the criteria for moderate depression. We provided a detailed explanation about the relationship between hypertension and depression, prescribed the same medication as prescribed at her last visit, referred the patient to a psychologist, and made a follow-up appointment.

Follow-up visit

The patient returned 1 month later with her husband and stated that she had visited the psychologist after the last emergency room visit. The psychologist interviewed her, used CIDI, and gave her a diagnosis of depression. She took sertraline (50 mg once a day)and followed up with the psychologist 2 weeks before. During the last month, she had taken 30-mg nifedipine controlled-release tablets once a day and her blood pressure was well-controlled.

Figure 1. Screening for depression in patients with coronary heart disease

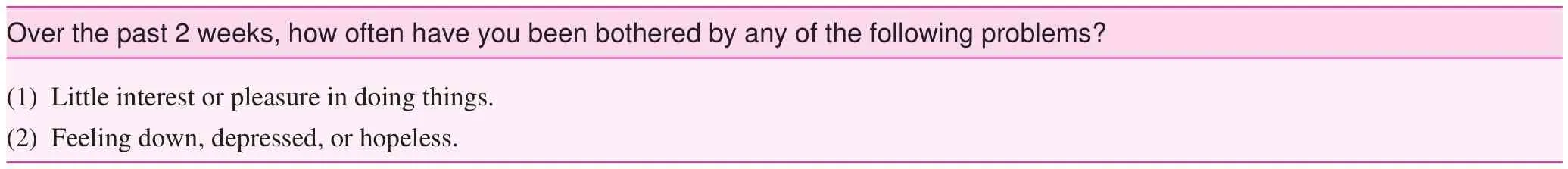

Table 1. Patient Health Questionnaire: 2 Items*

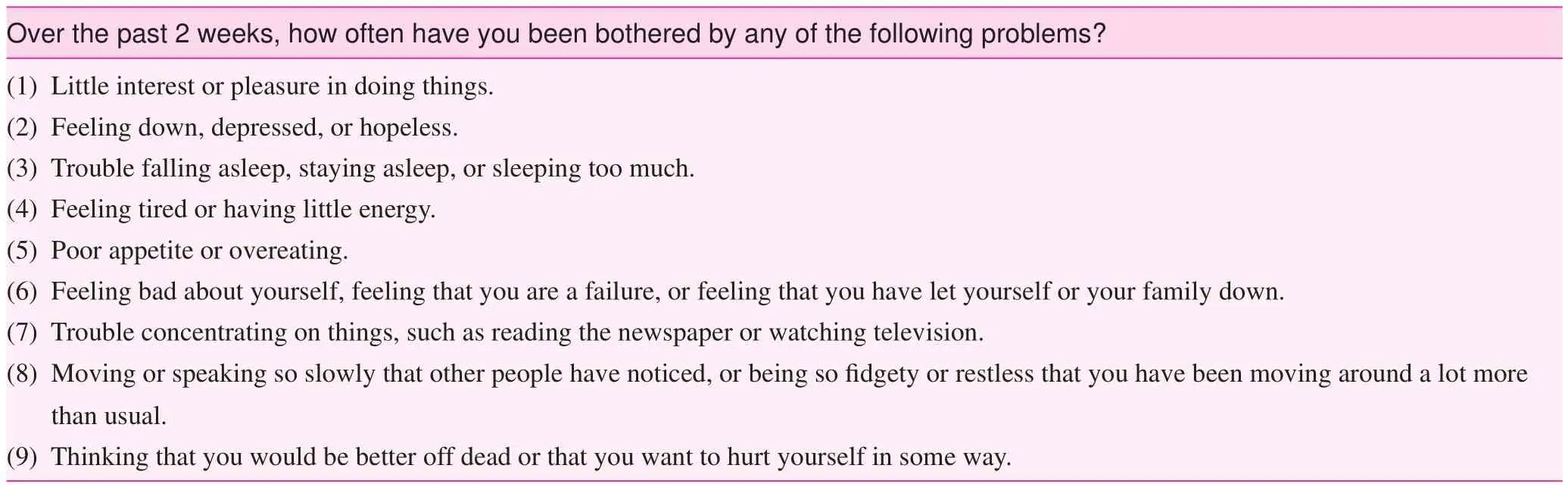

Table 2. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)* Depression Screening Scales

Question: Based on this case, what can we learn from it?

Answer:

? Pay more attention to the mental status of patients with cardiovascular disease because of the high prevalence of co-morbidity.

? Choose a suitable screening tool to assess mental disorders in patients with physical diseases.

? The ‘physical-mental’ treatment of cardiovascular disease cannot be conducted at one time and requires follow-up.

A Establish a trustworthy relationship:A few visits may be needed to establish a trustworthy relationship between the physician and the patient. The physician should let the patient trust the symptoms of long-term blood pressure fluctuation and avoid iatrogenic psychologic barriers during the process.

B Understand the patient:The physician should understand the patient’s viewpoint. The current patient worried that hypertension would lead to death from cerebral hemorrhage, like her father, and that her daughter would lose her mother. Such a belief will make her more stressed and lead to depression and fluctuations in blood pressure.

C Reassurance and explanation:It is important to explain the disease from a ‘bio-psycho-social’ perspective. Hypertension may come from pressure and negative mood, such as depression and anxiety. Also, if someone has hypertension, he or she will worry about it, pay more attention to their blood pressure level, and thus be at increased risk of developing a mental disorder.

D Reattribution:The physician should let the patient acknowledge their uncomfortable feelings regarding theiranxiety about the blood pressure. Reattribution depends on the above efforts, including the trustworthy relationship, understanding, reassurance, and explanation. Once reattribution is established, the physician can refer the patient to a psychologist if the screening meets the criteria, and implement appropriate treatment.

E Further management: Cognitive behavioral therapy, stress management techniques (such as, relaxation exercise and physical exercises), and pharmacologic treatment under the advice of a specialist should be considered.

Confict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1. ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJ, Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating group. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 2002;360:1347–60.

2. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 2005;365:217–23.

3. Ma YQ, Mei WH, Yin P, Yang XH, Rastegar SK, Yan JD. Prevalence of hypertension in Chinese cities: a meta-analysis of published studies. PLoS One 2013;8:e58302.

4. Department of Disease Control and Prevention, M. o. H. Report on chronic diseases in China. Beijing, China, 2006.

5. Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, Song Z, Ding Z, Pang S, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001–05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet 2009;373:2041–53.

6. Meng L, Chen D, Yang Y, Zheng Y, Hui R. Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hypertens 2012;30:842–51.

7. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13.

8. Manea L, gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J 2012;184:e191–6.

9. Lichtman JH, Bigger JT Jr, Blumenthal JA, Frasure-Smith N, Kaufmann Pg, Lespérance F, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation 2008;118:1768–75.

1. Department of Cardiology, The First Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an City of Shannxi Province, 710061, China

2. Faculty of Medicine, School of Primary Health Care, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Victoria 3165, Australia

Yanping Ren

Department of Cardiology, The First Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an City of Shannxi Province, 710061, China

e-mail: ryp0071@126.com

2 November 2013;

Accepted 30 December 2013

Family Medicine and Community Health2013年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2013年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Economic burden of inpatients with viral hepatitis B-related diseases and the infuencing factors

- Memory and behavior-related problems of patients with neurocognitive disorders and the attitudes of their caregivers

- Health-related behaviors in children of ethnic minorities and Han nationality in China

- Epidemiologic survey and analysis of mild cognitive impairment amongst community senior citizens of Changsha City

- Development of community health service-oriented computerassisted information system for diagnosis and treatment of respiratory diseases

- Family Medicine and Community Health