Biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: the endoscopic versus percutaneous approach

Seoul, Korea

Biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: the endoscopic versus percutaneous approach

Jongkyoung Choi, Ji Kon Ryu, Sang Hyub Lee, Dong-Won Ahn, Jin-Hyeok Hwang, Yong-Tae Kim, Yong Bum Yoon and Joon Koo Han

Seoul, Korea

BACKGROUND:For palliative treatment of the obstructive jaundice associated with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) has been performed. PTBD is preferred as an initial procedure. Little is known about the better option for patients with obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable HCC.

hepatocellular carcinoma; obstructive jaundice; endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage; percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage

Introduction

Jaundice occurs in 5%-44% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).[1-3]It is mainly caused by secondary parenchymal insufficiency due to advanced hepatitis and cirrhosis or diffuse tumor infiltration of the liver.[4]Rarely, obstructive jaundice is caused by tumor thrombi, hemobilia, intraductal tumor growth and extraluminal compression by tumor, or metastatic lymphadenopathy at the porta hepatis.[5]

In patients with obstructive jaundice caused by HCC, progressive jaundice is an immediate threat to survival in addition to a significant reduction of the quality of life secondary to the development of the associated pruritus, malaise and cholangitis.[6]Some of these patients can be treated by hepatic resection achieving long-term resolution of symptoms and occasional longterm survival.[7,8]However, the majority of the patients are not candidates for surgery because of either the advanced nature of disease or other significant comorbidity precluding surgery. In such cases, effective and lasting decompression of the biliary tree is a priority; this consists of positioning of a biliary endoprosthesis by the endoscopic or percutaneous approach.[4]Studies of nonsurgical biliary drainage in patients with HCC have mostly focused on the percutaneous approachnot the endoscopic one.[4,9,10]Whereas few studies on the endoscopic approach showed a significant benefit associated with the procedure. Additionally, the earlier literature described that endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) was somewhat more difficult in HCC patients with obstructive jaundice because of proximal biliary obstruction at the hilum, hypervascularity of tumors, underlying liver cirrhosis and poor hepatic functional reserve.[8]Therefore, physicians prefer percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) to manage obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable HCC. However, the endoscopic approach to biliary drainage is less invasive and more comfortable than the percutaneous one.[11]Moreover, the recent development of the endoscopic approach allows patients with distal bile duct obstruction and proximal bile duct obstruction to be easily managed by endoscopic stenting. Consequently, the endoscopic approach has been used as the standard practice for relief of obstructive jaundice in patients with unresectable malignant biliary obstruction due to cholangiocarcinoma and periampullary malignancies.[6,12,13]Currently, there is no study comparing ERBD with PTBD in patients with unresectable HCC. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ERBD compared with PTBD in the management of obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable HCC.

Methods

Patients

In this retrospective study, we evaluated patients with unresectable HCC aged ≥18 years who had received biliary drainage for the palliative treatment of obstructive jaundice between January 1, 2006 and May 30, 2010 at the Seoul National University Hospital and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. HCC was diagnosed according to (1) pathological findings or (2) an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level ≥200 ng/mL plus findings of HCC on a dynamic image or an AFP<200 ng/mL plus typical findings of HCC on two dynamic images in the patient with cirrhosis.[14]Patient eligibility was predicted by a total serum bilirubin level more than 3 mg/dL with dilatation of the bile duct observed on CT. The resectability of the tumor was determined by X-ray findings. Patients were excluded if they had hepatobiliary manipulation including hepatic resection, liver transplantation, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography or percutaneous cholangiography.

Procedures

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed to characterize the biliary stricture by large-or standard-channel duodenoscopes (TJF-240, JF-240, TJF-200, and JF-200; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed in patients using pull-type sphincterotomies. After confirmation of guidewire passage through the stricture, we inserted a 10F plastic stent (Percuflex Amsterdam biliary stent; Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass, USA) by a transpapillary approach. Proper placement of the stent across the stricture was confirmed by fluoroscopy.

For PTBD, a right (segment IV) or left (segment III) approach was determined on the location of bile duct obstruction. The appropriate intrahepatic bile ducts were accessed with a 21G Chiba needle under ultrasound guidance. A 5F catheter and a 0.035” hydrophilic guidewire were introduced into the accessed bile ducts. After dilation of the parenchymal tract, an 8.5F or 10F external drainage catheter (Ultrathane?; Cook Inc., Bloomington, USA) was inserted over the guidewire and positioned in the appropriate intrahepatic duct. The endoscopic approach was preferred as the initial drainage procedure when experienced endoscopists were available (two or three days per week). However, the percutaneous approach was performed in other situations. If the ERBD was rejected, PTBD was performed as a drainage procedure. Stent malfunction was suspected when a patient had signs of cholangitis or when the total serum bilirubin level increased ≥2-fold above the baseline level after the procedure.[15]When malfunction of the PTBD or ERBD was suspected clinically, subsequent endoscopic or percutaneous cholangiography was performed to confirm the occlusion and for reintervention, unless hepatic insufficiency progressed rapidly and the patient's condition deteriorated rapidly. The procedure was explained to all patients and informed consent was obtained.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of the study were successful drainage and drainage patency. Successful drainage was defined as either a decrease in bilirubin levels to less than 70% of the pretreatment value or near normalization (≤?2 mg/dL) within 2 weeks after a procedure.[9]Drainage patency was measured by the elapsed days between the procedure and either the first occlusion requiring reintervention or the date of death of the patient never experiencing stent occlusion. The secondary outcome measures were the patient's survival and procedure-related complications such as cholangitis, bleeding and pancreatitis. The overall survival was measured from the date of the intervention until thedate of death. Cholangitis was defined to be related to abdominal pain and fever (temperature ≥38 ℃) without any other infectious focus outside the hepatobiliary system that required antibiotic treatment within 24 hours after a procedure.[15]Pancreatitis was diagnosed when serum amylase levels increased to more than three times the normal limit (60-180 U/L) with notable persistent abdominal pain for more than 24 hours after drainage.[15]Significant bleeding indicated a decrease in the serum hemoglobin level of ≥2 mg/dL with a requirement for blood transfusion or a hemostatic procedure (including surgery) after a drainage. Drainage disposition referred to a decreased amount of bile juice without cholangitis that required a re-intervention within 2 weeks after a procedure. The procedurerelated mortality was defined as death directly related to a complication occurring immediately after the endoscopic or percutaneous procedure.

Data were collected for other factors of interest such as patient demographics, the cause or severity of liver disease, staging of HCC, the type of bile duct obstruction, the presence of portal vein thrombosis and antitumor therapy for HCC before or after biliary drainage. For evaluation of the liver function status, the Child-Pugh class was used for all patients.[16]For staging of HCC, patients were classified according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system.[14,17]The types of obstruction were confirmed by direct cholangiography or CT as obstruction or stenosis of the biliary tree.[4,18]They included type I: bile duct tumor (BDT) located in the secondary branch of the biliary tree; type II: BDT extending to the first branch of the biliary tree; type IIIa: BDT extending to the common hepatic duct (CHD); type IIIb: an implanted tumor growing in the CHD; type IV: floating tumor debris from the ruptured tumor in the CBD; and type V: the presence of malignant lymph node enlargement compressing the common hepatic or bile duct leading to obstruction.

The data of the patients were extracted by medical record review, telephone interviews, and the national mortality database. The institutional review board approved the study.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with SPSS 17.0K for windows (SPSS Korea, Seoul, Korea). Characteristics of the study groups were compared using Student'sttest for continuous variables and the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for the categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the significance of variables with respect to the procedure type and treatment results. Drainage patency and survival data were evaluated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the logrank test. To identify the independent factors associated with these endpoints, multivariate analysis was made with a Cox proportional hazard model.P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

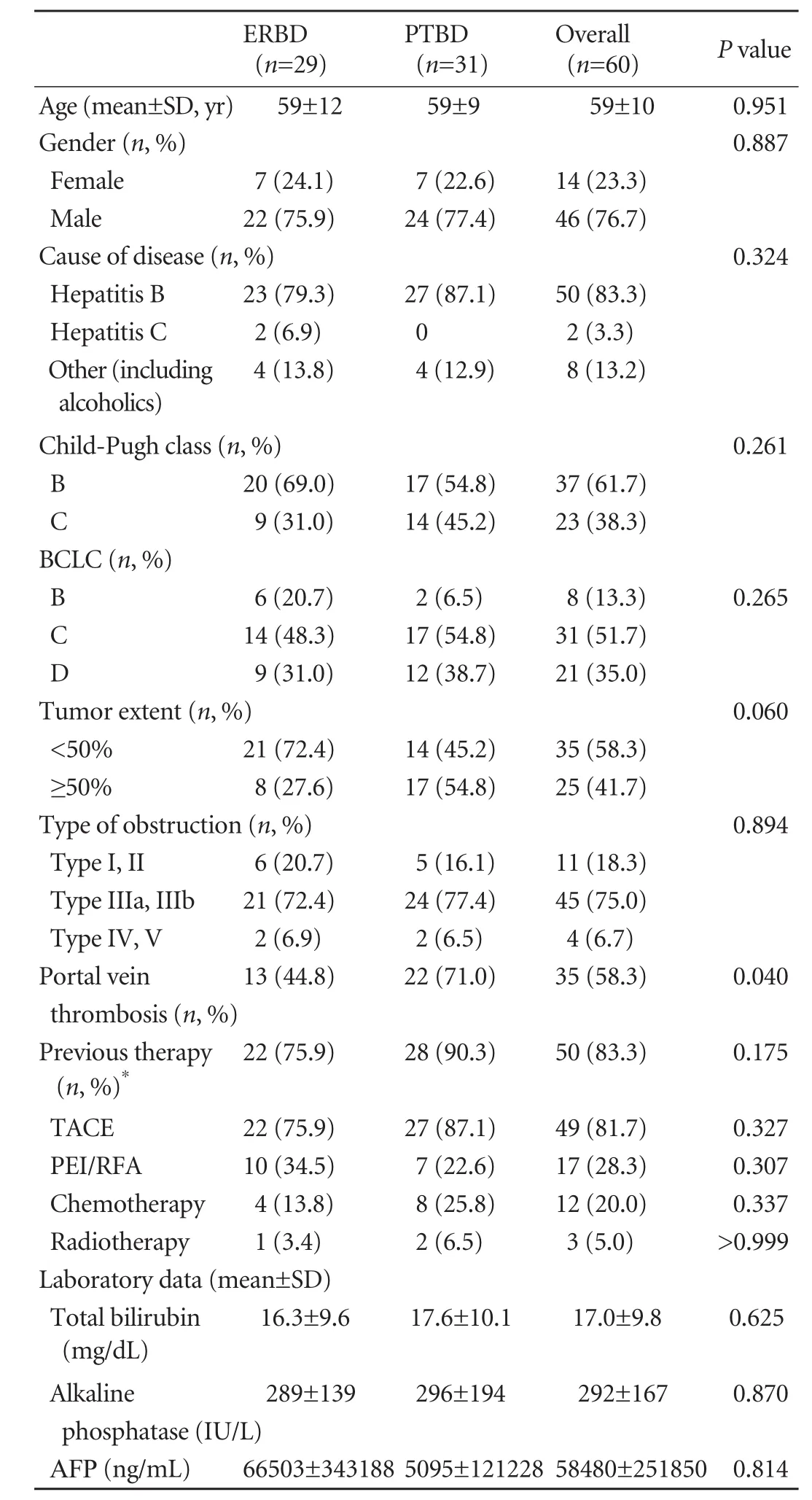

In the 60 patients who had received palliative biliary drainage, 46 were men and 14 women, with a mean age of 59±10 years. Fifty patients had been treated for HCC and 10 were newly diagnosed with HCC. The patients in the PTBD group showed poor results in Child-Pugh class, BCLC stage and tumor extent, in which no significant difference was found. But the number of patients with portal vein thrombosis was higher in the PTBD group than in the ERBD group (13/29 vs 22/31, respectively,P=0.04) (Table 1). One patient underwent PTBD after ERCP because of difficulty in passing endoscopically a guidewire into the stricture site.

Primary outcomes

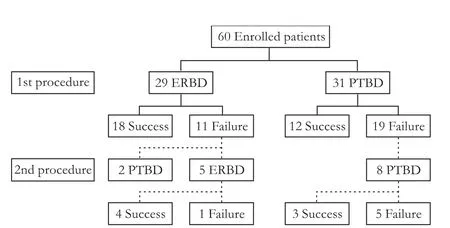

Drainage after the initial procedure was performed successfully in 30 (50%) patients. The success rate of drainage was higher in the ERBD group (18/29, 62.1%) than in the PTBD group (12/31, 38.7%), but there was no significant difference between the two groups (P=0.071) (Fig. 1). Two of 11 patients whose first ERBD failed received PTBD because of severe cholangitis occurring within three days of ERBD, although the endoscopic stent across the stricture was confirmed by fluoroscopy during the initial procedure. For the whole drainage procedure performed, the success rate of drainage was significantly higher in the ERBD group (22/29, 75.9%) than in the PTBD group (15/31, 48.4%) (P=0.029). No significant difference in baseline characteristics such as Child-Pugh class (P=0.082), BCLC stage (P=0.472), tumor extent (P=0.193), type of obstruction (P=0.830) and portal vein thrombosis (P=0.394) was observed between patients who had a successful drainage and those who did not. Multivariate analysis showed that ERBD was associated with a higher probability of successful drainage, but there was no significant difference [hazard ratio (HR)=3.56; 95% CI: 0.97-12.90;P=0.057].

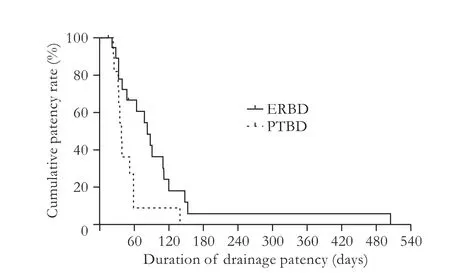

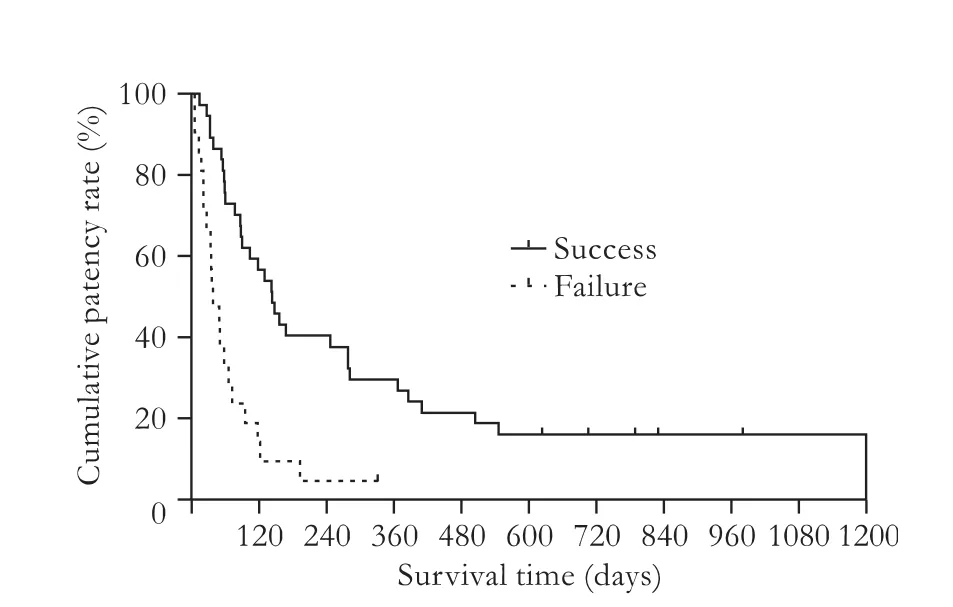

Among 30 patients who had a successful drainage, the median duration of drainage patency was 82 days (interquartile range (IQR): 38-110) in the ERBD group and 37 days (IQR: 31-58) in the PTBD group (Fig. 2)(P=0.021). Seven patients (38.9%) in the ERBD group and 4 patients (33.3%) in the PTBD group underwent transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) after a successful drainage (P>0.999). One of the 7 patients also received radiotherapy. In the subgroup analysis of 30 patients who had had a successful drainage with transarterial chemoembolization, the median duration of drainage was significantly longer in the treated group (109 days, IQR: 63-139) than in the untreated group (38 days, IQR: 31-58) (P=0.003). Regression analysis showed that ERBD (HR=0.36; 95% CI: 0.15-0.85;P=0.020) followed by TACE (HR=0.27; 95% CI: 0.10-0.65;P=0.004) was associated with a lower probability of drainage failure.

Table 1.Baseline characteristics in the ERBD group compared wih the PTBD group

Fig. 1.Algorithm for procedure in patients with HCC and obstructive jaundice. ERBD: endoscopic biliary drainage; PTBD: percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

Fig. 2.Kaplan-Meier estimation of cumulative drainage patency rates according to the biliary drainage method in 30 patients who had a successful drainage initially. Cumulative drainage patency rates were significantly higher in the ERBD group than those in the PTBD group (P=0.021). ERBD: endoscopic biliary drainage; PTBD: percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

Secondary outcomes

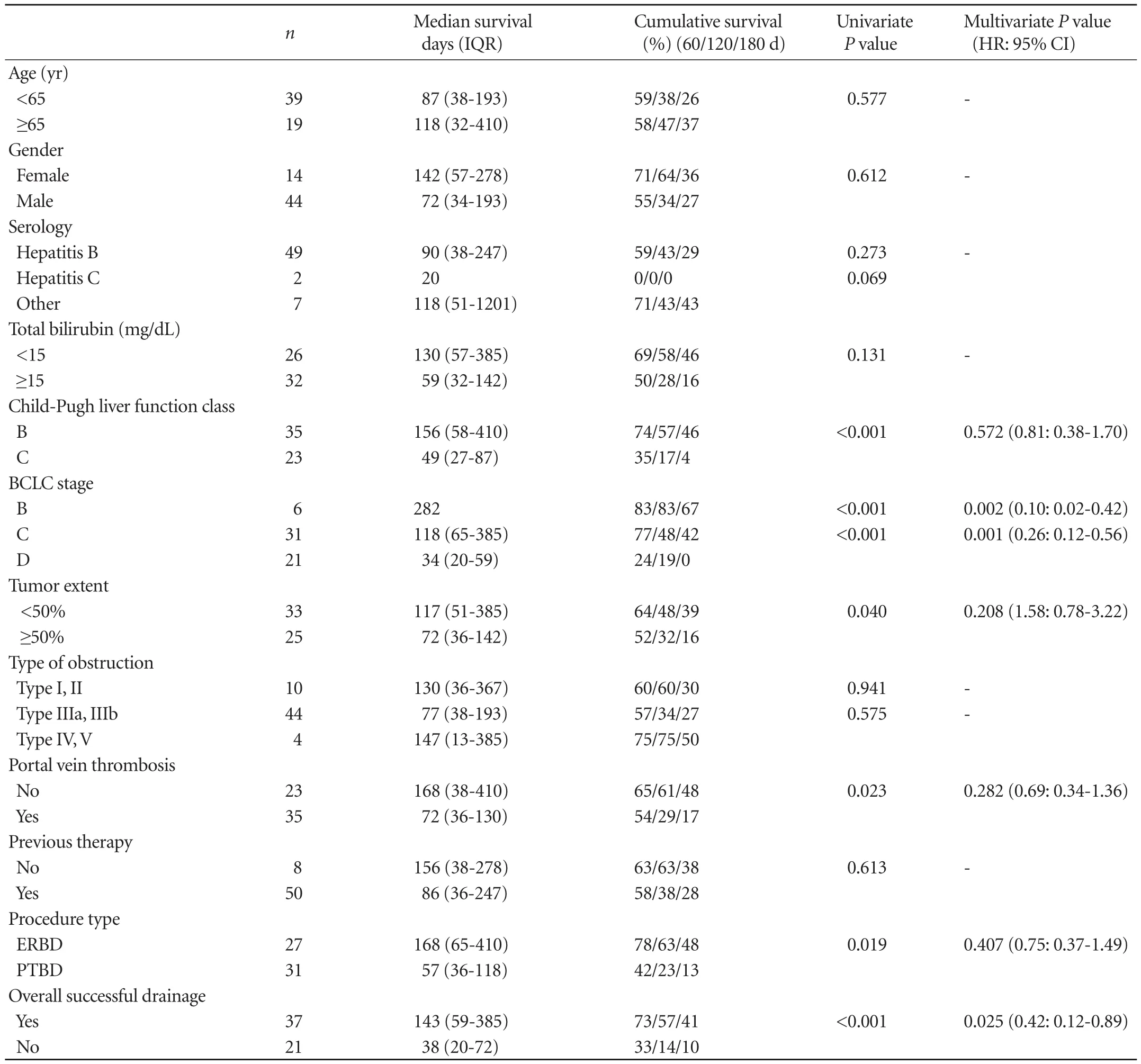

At the time of analysis, 52 patients died (23 patients in the ERBD group and 29 in the PTBD group) and 6 were alive. Two patients received subsequent PTBD because of early malfunction of ERBD and survived more than two years. They were not included for comparison of survival because of technical errors. The median survival time of patients was significantly longer in the ERBD group (168 days, IQR: 65-410) than in the PTBD group (57 days, IQR: 36-118) (P=0.019). The median survival time was significantly longer in patients who had a successful drainage (143 days, IQR: 59-385) than in those who did not (38 days, IQR: 20-72) (P<0.001) (Fig. 3). Regressionanalysis showed that the effect of BCLC staging (HR= 0.10; 95% CI: 0.02-0.42;P=0.002) and the overall rate of successful drainage (HR=0.42; 95% CI: 0.20-0.89;P=0.025) contributed to a lower probability of death. This was not found in the ERBD group (HR=0.75; 95% CI: 0.37-1.49;P=0.407) (Table 2). Moreover, once biliary palliation was successful, no difference was found in survival between the ERBD (247 days, IQR: 90-505) and PTBD groups (86 days, IQR: 55-142) (P=0.100).

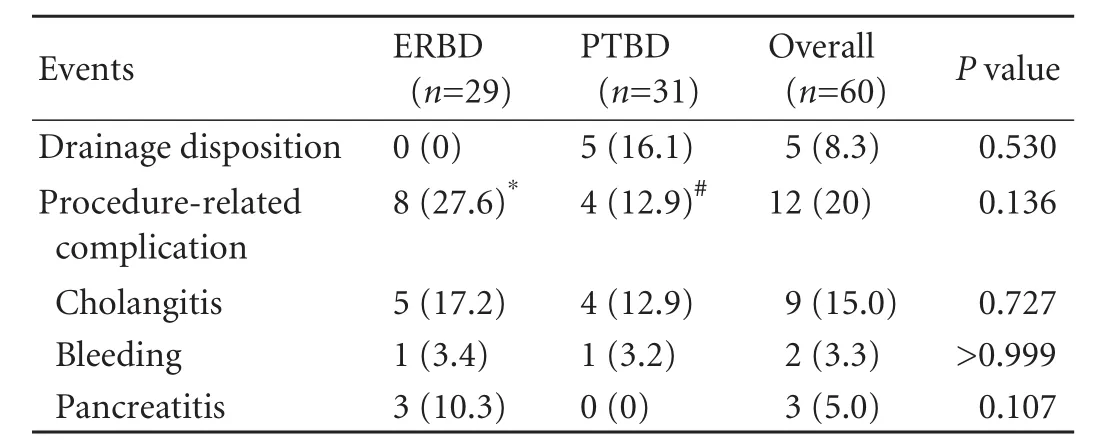

The overall incidence of procedure-related complications was 27.6% (8 patients) in the ERBD group and 12.9% (4) in the PTBD group (Table 3). Cholangitis was the frequent event in both groups. Two patients in the ERBD group and 3 in the PTBD group had to replace biliary drainage catheter or stent for cholangitis. One patient with cholangitis-related bleeding after PTBD had a successful embolization. Others with procedure-related complications were managed conservatively. Five patients in the PTBD group required additional interventions because of disposition of the external drainage catheter.

Table 2.Prognostic factors associated with survival in all patients shown by univariate and multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression

Fig. 3.Cumulative survival rates in 58 patients according to overall successful drainage. Cumulative survival rates were significantly higher in patients who had successful drainage compared with those who did not have successful drainage (P<0.001).

Table 3.Procedure-related complications

Discussion

This study was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of ERBD compared with PTBD for palliative treatment of obstructive jaundice in patients with unresectable HCC. Studies have compared the surgical and nonsurgical approaches.[19,20]However, no study has been carried out to compare the methods of palliative drainage, or to investigate the best palliative treatment of obstructive jaundice in patients with unresectable HCC. The present study showed that ERBD had a longer duration of drainage than PTBD and that ERBD might be used as the treatment option to improve obstructive jaundice in patients with unresectable HCC.

In HCC patients with obstructive jaundice, the reported rates of successful ERBD and PTBD were 54.5%-72%[21,22]and 18.2%-59.1%,[5,23]respectively, which are consistent with our study. In the present study, the duration of stent patency in the ERBD group was significantly longer than in the PTBD group, which might be due to the percutaneous approach for external drainage not internal drainage. In Hong's study,[9]the success rate was 73% and the overall mean stent patency was 149.8 days (range 12-790), which were higher than those in the PTBD group in the present study. These findings may be explained by the difference between internal and external drainage. In our study, the overall incidence of procedure-related complications was higher in the ERBD group than in the PTBD group, but with no significant difference, which might be due to the relatively low incidence of procedure-related complications and avoidance of pancreatitis in the PTBD group. All patients with pancreatitis recovered after conservative therapy. The severity and incidence of cholangitis and bleeding in the ERBD group were similar to those in the PTBD group.

Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that successful drainage was a significant factor associated with survival in the present study. Once successful drainage was achieved, no significant difference in the overall survival time was found between the two methods. This finding suggests that palliative treatment of biliary stasis is associated with the survival of patients with HCC. After reduction of the degree of jaundice by drainage, TACE prolonged the survival of patients with obstructive jaundice caused by HCC.[4,19,24]The mean survival time of patients treated with biliary drainage alone ranged from 2.5 to 4.5 months, while that of patients using combined palliative therapies ranged from 8 to 13.4 months.[4,19,25]These findings are consistent with those of the present study. But our study was based on small samples (≤30 cases). Hence further study is needed to assess these findings and their implications in clinical practice.

The current study is limited by its retrospective nature. It is possible that patients who underwent ERBD could be more suitable than those in the PTBD group for the endoscopic approach because endoscopists usually choose the first one of the two biliary drainages, endoscopic vs percutaneous. Possibly the difference in the baseline characteristics of patients may influence the success rate of biliary decompression in the ERBD group compared with the PTBD group. Studies[5,13,21,22]reported that predictive factors for successful drainage included portal vein thrombosis, type of obstruction, poor liver functional reserve and elevated bilirubin level. These findings were in favor of our conclusion that ERBD was beneficial in spite of the differences in the baseline characteristics. However, owing to the possible influence of selection bias, the results should not be generalized to patients with obstructive jaundice and randomized prospective studies are needed to confirm the benefits and indications of ERBD.

In conclusion, our study indicated that ERBD has a longer duration of drainage patency than PTBD. However,the difference in the rates of successful drainage is not statistically significant. Therefore, endoscopic biliary drainage might be chosen as the initial treatment of obstructive jaundice in patients with unresectable HCC.

Contributors:CJ and RJK contributed equally to this work. LSH proposed the study. CJ and RJK performed research and wrote the first draft. CJ collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. LSH is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Kew MC, Geddes EW. Hepatocellular carcinoma in rural southern African blacks. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982;61:98-108.

2 Ihde DC, Sherlock P, Winawer SJ, Fortner JG. Clinical manifestations of hepatoma. A review of 6 years' experience at a cancer hospital. Am J Med 1974;56:83-91.

3 Lau WY, Leow CK, Leung KL, Leung TW, Chan M, Yu SC. Cholangiographic features in the diagnosis and management of obstructive icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB Surg 2000;11:299-306.

4 Lai EC, Lau WY. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with obstructive jaundice. ANZ J Surg 2006;76:631-636.

5 Lee JW, Han JK, Kim TK, Choi BI, Park SH, Ko YH, et al. Obstructive jaundice in hepatocellular carcinoma: response after percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and prognostic factors. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2002;25:176-179.

6 Garcea G, Ong SL, Dennison AR, Berry DP, Maddern GJ. Palliation of malignant obstructive jaundice. Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:1184-1198.

7 Chen CL, Huang SM, Chien CH, Chang TT, Yu CY, Lee JC. Successful resection of a minute icteric hepatocellular carcinoma--case report. Hepatogastroenterology 1994;41:503-505.

8 Qin LX, Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol 2003;9:385-391.

9 Hong HP, Kim SK, Seo TS. Percutaneous metallic stents in patients with obstructive jaundice due to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;19:748-754.

10 Sasahira N, Tada M, Yoshida H, Tateishi R, Shiina S, Hirano K, et al. Extrahepatic biliary obstruction after percutaneous tumour ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: aetiology and successful treatment with endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation. Gut 2005;54:698-702.

11 Paik WH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Lee SH, Yoon CJ, Kang SG, et al. Palliative treatment with self-expandable metallic stents in patients with advanced type III or IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a percutaneous versus endoscopic approach. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:55-62.

12 Ornellas LC, Stefanidis G, Chuttani R, Gelrud A, Kelleher TB, Pleskow DK. Covered Wallstents for palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: primary stent placement versus reintervention. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:676-683.

13 Cho HC, Lee JK, Lee KH, Lee KT, Paik S, Choo SW, et al. Are endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage effective for obstructive jaundice caused by hepatocellular carcinoma? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;23:224-231.

14 Bruix J, Sherman M; Practice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2005;42:1208-1236.

15 Yang KY, Ryu JK, Seo JK, Woo SM, Park JK, Kim YT, et al. A comparison of the Niti-D biliary uncovered stent and the uncovered Wallstent in malignant biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:45-51.

16 Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646-649.

17 Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2003;362:1907-1917.

18 Ueda M, Takeuchi T, Takayasu T, Takahashi K, Okamoto S, Tanaka A, et al. Classification and surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with bile duct thrombi. Hepatogastroenterology 1994;41:349-354.

19 Xiangji L, Weifeng T, Bin Y, Chen L, Xiaoqing J, Baihe Z, et al. Surgery of hepatocellular carcinoma complicated with cancer thrombi in bile duct: efficacy for criteria for different therapy modalities. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2009;394:1033-1039.

20 Hu J, Pi Z, Yu MY, Li Y, Xiong S. Obstructive jaundice caused by tumor emboli from hepatocellular carcinoma. Am Surg 1999;65:406-410.

21 Matsueda K, Yamamoto H, Umeoka F, Ueki T, Matsumura T, Tezen T, et al. Effectiveness of endoscopic biliary drainage for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma associated with obstructive jaundice. J Gastroenterol 2001;36:173-180.

22 Martin JA, Slivka A, Rabinovitz M, Carr BI, Wilson J, Silverman WB. ERCP and stent therapy for progressive jaundice in hepatocellular carcinoma: which patients benefit, which patients don't? Dig Dis Sci 1999;44:1298-1302.

23 Kubota Y, Seki T, Kunieda K, Nakahashi Y, Tani K, Nakatani S, et al. Biliary endoprosthesis in bile duct obstruction secondary to hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Imaging 1993;18:70-75.

24 Doppman JL, Girton M, Vermess M. The risk of hepatic artery embolization in the presence of obstructive jaundice. Radiology 1982;143:37-43.

25 Huang JF, Wang LY, Lin ZY, Chen SC, Hsieh MY, Chuang WL, et al. Incidence and clinical outcome of icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17: 190-195.

Received December 27, 2011

Accepted after revision May 22, 2012

ixty patients who had

ERBD or PTBD for the palliative treatment of obstructive jaundice caused by unresectable HCC between January 2006 and May 2010 were included in this retrospective study. Successful drainage, drainage patency, and the overall survival of patients were evaluated.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2012;11:636-642)

Author Affiliations: Department of Internal Medicine and Liver Research Institute (Choi J, Ryu JK, Lee SH, Ahn DW, Hwang JH, Kim YT and Yoon YB) and Department of Radiology (Han JK), Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea; Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Korea (Lee SH and Hwang JH); Department of Internal Medicine, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea (Choi J); Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea (Ahn DW)

Sang Hyub Lee, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 300 Gumi-dong, Bundang-gu, Seongnamsi, Gyeonggi-do 463-707, Korea (Tel: 82-31-787-7042; Fax: 82-31-787-4051; Email: gidoctor@snubh.org)

? 2012, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(12)60237-9

RESULTS:Univariate analysis revealed that the overall frequency of successful drainage was higher in the ERBD group (22/29, 75.9%) than in the PTBD group (15/31, 48.4%) (P=0.029); but multivariate analysis showed marginal significance (P=0.057). The duration of drainage patency was longer in the ERBD group than in the PTBD group (82 vs 37 days, respectively,P=0.020). Regardless of what procedure was performed, the median survival time of patients who had a successful drainage was much longer than that of the patients who did not have a successful drainage (143 vs 38 days, respectively,P<0.001).

CONCLUSION:Besides PTBD, ERBD may be used as the initial treatment option to improve obstructive jaundice in patients with unresectable HCC if there is a longer duration of drainage patency after a successful drainage.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2012年6期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2012年6期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer

- Risk factors and incidence of acute pyogenic cholangitis

- Endoscopic sphincterotomy associated cholangitis in patients receiving proximal biliary self-expanding metal stents

- Gallstone-related complications after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a prospective study

- Inhibiting the expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha attenuates lipopolysaccharide/ D-galactosamine-induced fulminant hepatic failure in mice

- Changes of serum alpha-fetoprotein and alpha-fetoprotein-L3 after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic significance