Antioxidant effects of the orientin and vitexin in Trollius chinensis Bunge in D-galactose-aged mice**★

Fang An, Guodong Yang, Jiaming Tian, Shuhua Wang

College of Pharmacy, Hebei North University, Zhangjiakou 075000, Hebei Province, China

Antioxidant effects of the orientin and vitexin inTrollius chinensisBunge in D-galactose-aged mice**★

Fang An, Guodong Yang, Jiaming Tian, Shuhua Wang

College of Pharmacy, Hebei North University, Zhangjiakou 075000, Hebei Province, China

Total flavonoids are the main pharmaceutical components ofTrollius chinensisBunge, and orientin and vitexin are the monomer components of total flavonoids inTrollius chinensisBunge. In this study, an aged mouse model was established through intraperitoneal injection of D-galactose for 8 weeks, followed by treatment with 40, 20, or 10 mg/kg orientin, vitexin, or a positive control (vitamin E)viaintragastric administration for an additional 8 weeks. Orientin, vitexin, and vitamin E improved the general medical status of the aging mice and significantly increased their brain weights. They also produced an obvious rise in total antioxidant capacity, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase levels in the serum, and the levels of superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase, Na+-K+-ATP enzyme, and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATP enzyme in the liver, brain and kidneys. In addition, they significantly reduced malondialdehyde levels in the liver, brain and kidney and lipofuscin levels in the brain. They also significantly improved the neuronal ultrastructure. The 40 mg/kg dose of orientin and vitexin had the same antioxidant capacity as vitamin E. These experimental findings indicate that orientin and vitexin engender anti-aging effects through their antioxidant capacities.

Trollius chinesisBunge; orientin; vitexin; total flavonoids inTrollius chinensisBunge; D-galactose; antioxidation; aging; traditional Chinese medicine; regeneration; neural regeneration

Research Highlights

(1) Because orientin and vitexin have the same chemical constitution, we compared these antioxidantsin vivoto determine the optimal structure-activity relationship for anti-aging compounds.

(2) Orientin and vitexin have a high content of the total flavonoidTrollius chinensisBunge, and they improved the general medical conditions and increased the brain weights of mice with D-galactose-induced aging.

(3) Orientin and vitexin clearly increased the activity of the antioxidase system and the levels of ATPase in the serum and tissue of D-galactose-aged mice.

(4) Using advanced light and electron microscopy, we observed neuronal cell injuries in mice with D-galactose-induced aging, and improvements in neuronal cell structure and function in these mice following treatment with orientin and vitexin, which at the 40 mg/kg dose of orientin and vitexin was similar to the antioxidant effects of vitamin E.

INTRODUCTlON

Aging is a process whereby body functions degenerate as organs mature[1]. The free radical damage doctrine proposed by Harman[2]in 1956 has the most influence on many aging theories. This doctrine proposes that aging is a phenomenon of accumulating macromolecular damage that destroys balance in the system, and leads to loss of life-maintaining abilities. Free radicals produce oxidative damage on active molecules[3]. Excessive reactive oxygen species can cause oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, or lipids[4].

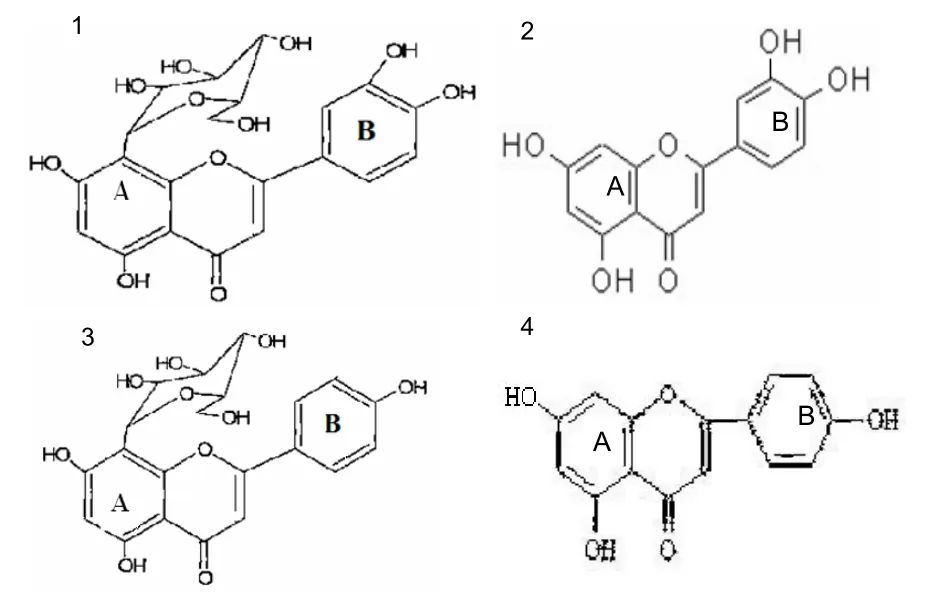

In recent years, anti-aging drugs from plants have shown great potential and have provided a unique chemical structure to research new anti-aging drugs[5]. Flavonoids have a complex structure, are signaling molecules in plants, and have significant anti-aging effects.Trollius chinensis, dried flowers ofTrollius chinensisBunge, has been used as an important traditional Chinese medicine for a long time. This plant grows widely in the southwest, northwest, northeast, and Taiwanese areas[6]. It is used for the treatment of aphtha, laryngitis, light fever, atrophy of the gums, ear ache, ophthalmalgia, and for eyesight improvements and as an anti-miasma drug. It has been used widely to treat colds, fever, chronic tonsillitis, acute tympanitis, urinary tract infections, and other inflammations[7-8]. The main chemical compositions ofTrollius chinesisare flavonoids, organic acids, aetherolea, and polycose[9-15]. Modern pharmacological studies show that the total flavonoids inTrollius chinensisBunge possess antiviral, antioxidant, anticancer and other pharmacological activities[16-20]. Previous studies[21-23]show that the content of orientin and vitexin is higherin the Flavone ofTrollius chinesis, and these flavonoids belong to the flavone c-glycoside class. Orientin possesses antithrombus and antioxidation properties, and protects against myocardial ischemic-anoxic injuries[24-26]. Vitexin has antiviral, antioxidant, and anticancer effects, and it protects against ischemic myocardial injuries. It may produce these effects by coronary and myocardial blood flow, reducing plasma viscosity, enhancing erythrocyte deformability, and inhibiting thrombosis[25,27-29]. Orientin and vitexin have better effects than resveratrol in suppressing growth and inducing apoptosis in human esophageal carcinoma EC109 cells, which is another Flavone ofTrollius chinesis[30]. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The flavonoids orientin and vitexin scavenge O2-, ·OH, and 1,1-Diphenyl-2- picrylhydrazyl radical 2,2-Diphenyl-1-(2,4,6- trinitrophenyl)hydrazyl free radicalsin vitroand protect red blood cells[31-32]. Pharmacokinetic studies show that orientin and vitexin occur at the highest concentration in the kidney in rabbits[33-34]. As such, we hypothesized that orientin and vitexin have marked antioxidant capacitiesin vivo. Through a search of the literature, we found that orientin and vitexin have the same chemical constitution as cyanidenon and pelargidenon[35](Figure 1).

Figure 1 Chemical structures of orientin and vitexin.

Fiavone-Cglycosides have strong anti-inflammatory effects, which are related to structure-function relationships[36]. Similar to vitexin and pelargidenon, a C-8 ring is more common in orientin than cyanidenon. The difference in the antioxidant effects of orientin and vitexinin vivois that orientin has a phenolic hydroxyl group, which sparked our interest. There is currently no report regarding the antioxidant effects of orientin and vitexinin vivo. In this study, we adopted a D-galactoseinduced aging mouse model to compare the effects of orientin and vitexin with those of vitamin E, in a broad attempt to investigate their antioxidant capacities.

RESULTS

Quantitative analysis of experimental animals

A total of 90 animals were randomly chosen from 120 Kunming mice, then assigned equally into nine groups: the control, model, high-, medium-, and low-dose orientin, and high-, medium-, and low-dose vitexin groups, as well as a vitamin E group. Except for the control group, each mouse was intraperitoneally injected with D-galactose for 8 weeks to establish the aging model. After the model was successfully established, the vitamin E group was given 20 mg/kg vitamin E, and the high-, medium-, low-dose groups of orientin and vitexin were treated for additional 8 weeks with 40, 20, or 10 mg/kg of orientin or vitexin. The remaining 30 mice were used to verify the successful establishment of the aging model, then equally divided into a control group and a model group. The total levels of superoxide dismutase and malondialdehyde in the serum of the mice were measured to verify the successful establishment of the aging model.

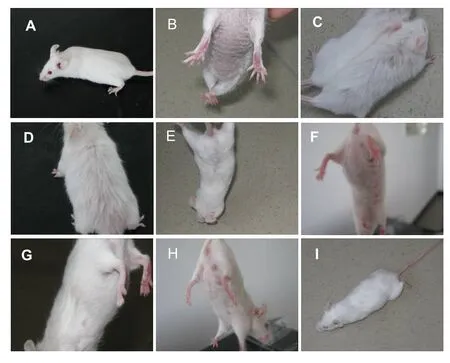

Orientin and vitexin improved the appearance of D-galactose-aged mice

The mice in the model group were dispirited and exhibited less activity, loss of hair, and yellowish withered hair, especially in the abdomen, compared with the mice in the control group. After orientin, vitexin, or vitamin E treatments, the appearance, activity, and hair color and luster of aged mice all improved, and the improvement was more obvious in high-dose orientin and vitexin groups. The medium- and low-dose orientin and vitexin treatments were significantly different than the vitamin E treatment, whereas the high-dose treatment was not (Figure 2).

Figure 2 General condition of mice.

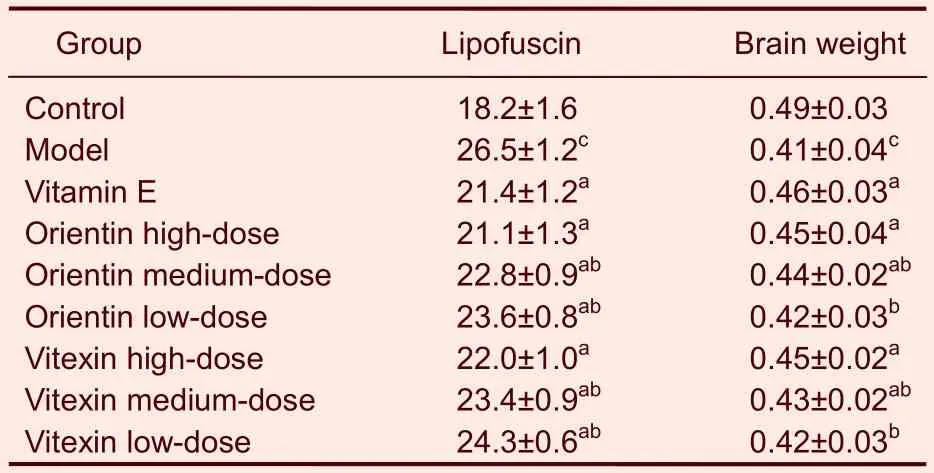

Orientin and vitexin increased the brain weights of D-galactose-aged mice

Compared with the mice in the control group, the brain weights of the aged mice in the model group were lower (P<0.01). The mice in the high- and medium-dose orientin or vitexin groups, as well as the mice in the vitamin E groups, had higher brain weights than the mice in the model group (P<0.05,P<0.01). The mice in the low-dose group did not exhibit any statistically significant effects. High, medium and low doses of orientin produced no significant differences compared with the same dose of vitexin. The mice in the medium- and low-dose orientin or vitexin groups had less delayed encephalatrophy than those in the vitamin E (P<0.05). Otherwise, the high doses of orientin or vitexin were not significantly different than vitamin E treatment (Table 1).

Table 1 The influence of orientin and vitexin on lipofuscin (μg) levels and brain weights (g) in D-galactose-aged mice

Orientin and vitexin increased the activity of the antioxidase system and levels of ATPase in the serum and tissue of D-galactose-aged mice

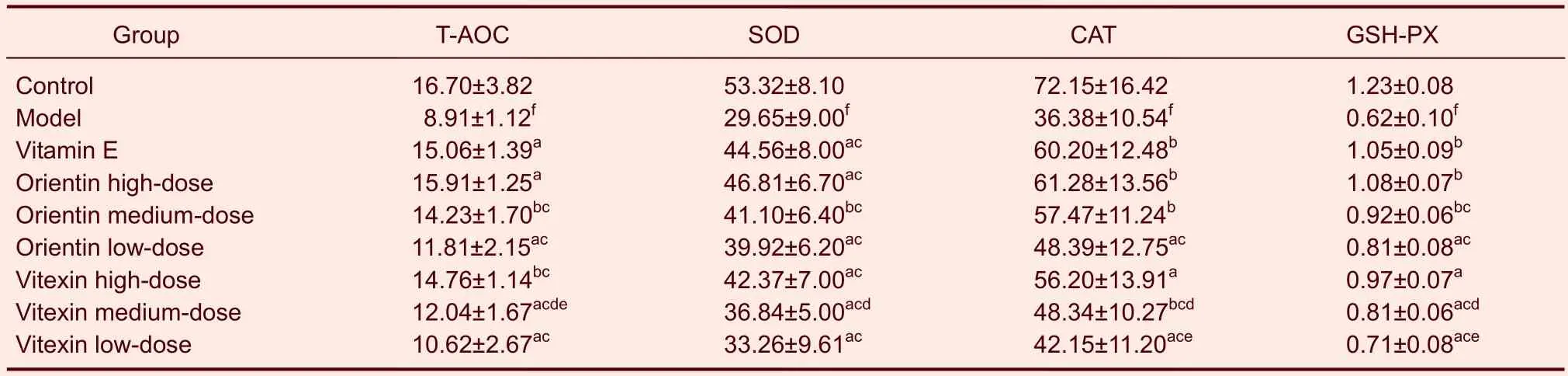

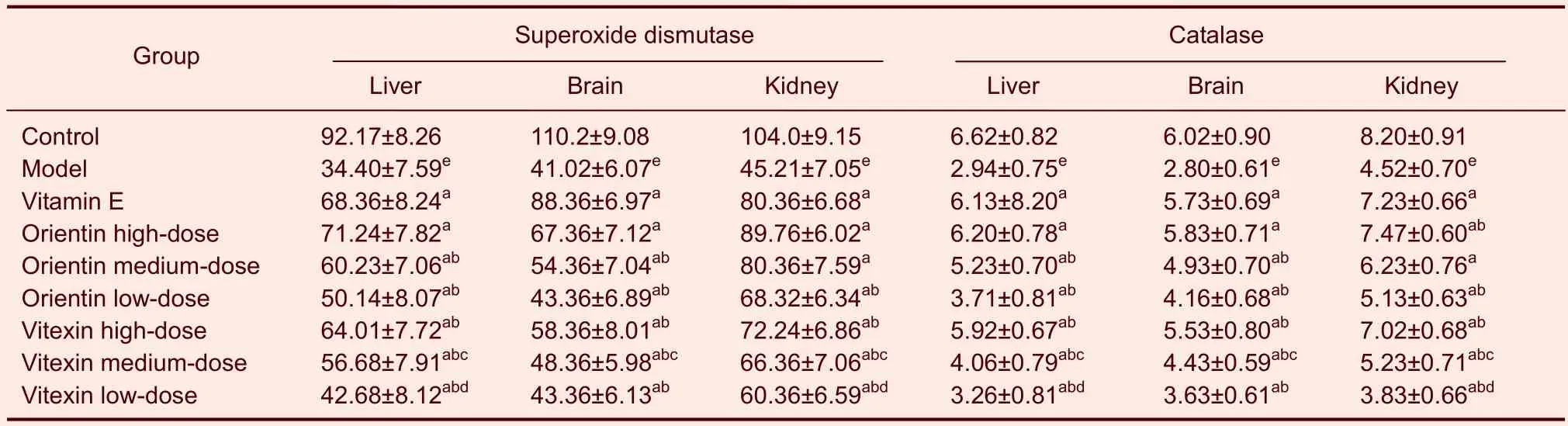

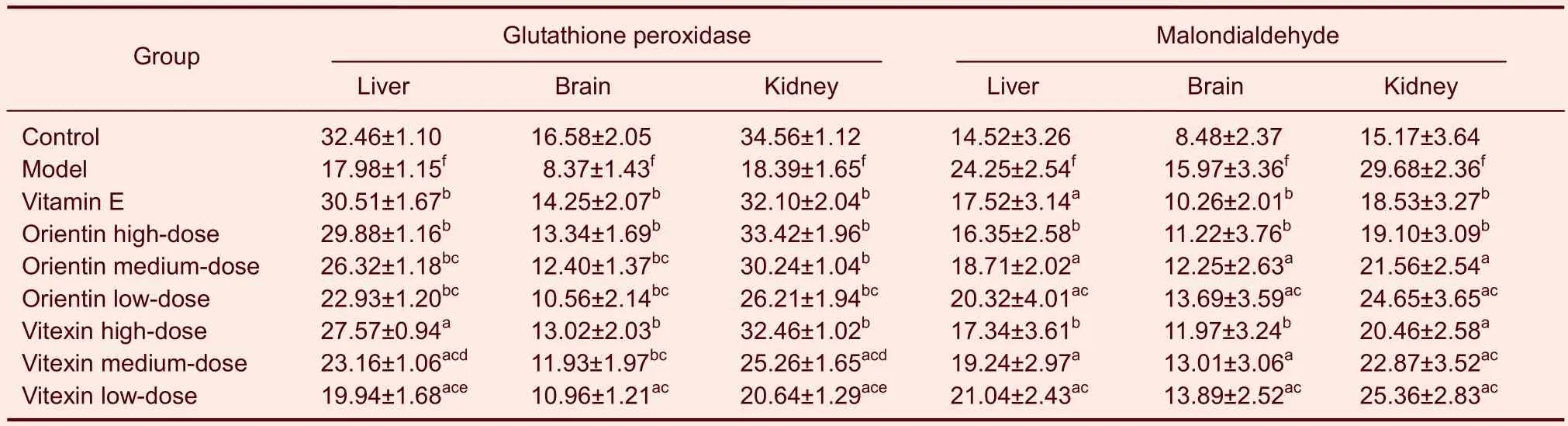

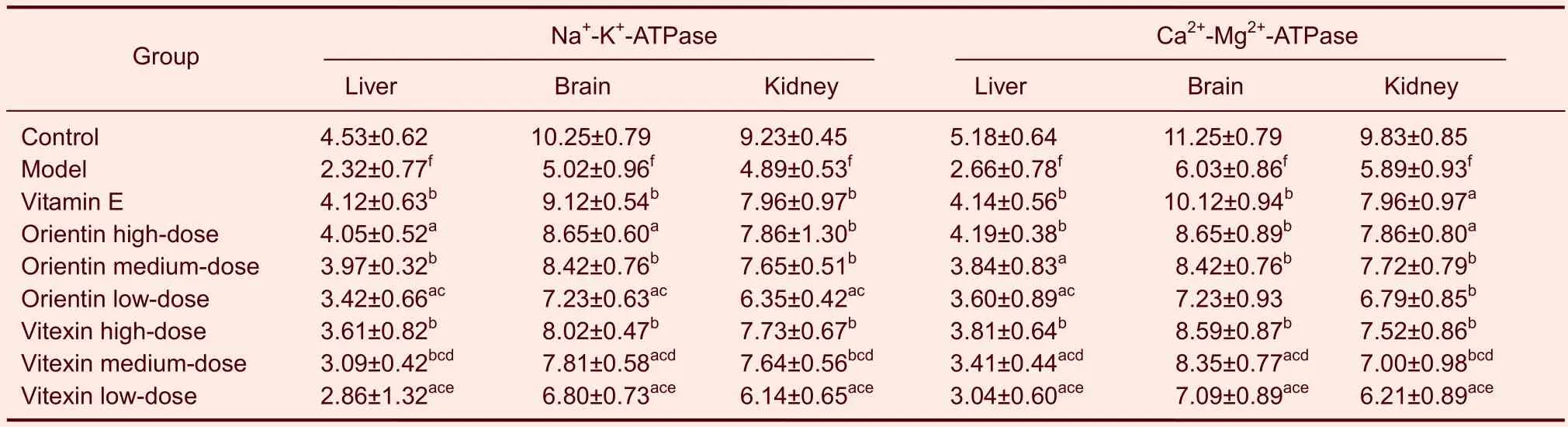

Compared with the mice in the control group, antioxidase activity in mouse serum was significantly lower in mice in the model group (P<0.01). Compared with the mice in the model group, mice treated with orientin or vitexin at all doses exhibited significantly increased total antioxidant capacities, levels of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in serum, and levels of superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, Na+-K+-ATP, and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATP in their liver, brains, and kidneys (P<0.05 orP<0.01). The medium and low doses of orientin increased antioxidase and ATPase levels in serum and tissue more than the same dose of vitexin (P<0.05). Compared with the mice in the vitamin E group, the orientin- and vitexin-treated mice exhibited higher antioxidase and ATPase levels in serum and tissue (P<0.05). The high doses of orientin or vitexin were not significantly different than vitamin E (Tables 2–5).

Orientin and vitexin reduced the content of malondialdehyde in the tissue and lipofuscin in the brains of D-galactose-aged mice

Compared with the mice in the control group, the contents of malondialdehyde in tissue and those of lipofuscin in the brain were significantly higher in the mice in the model group (P<0.01). Compared with the mice in the model group, all orientin or vitexin treatments significantly decreased malondialdehyde and lipofuscin content (P<0.05,P<0.01). The medium and low doses of orientin had stronger effects on the content of malondialdehyde than the same dose of vitexin (P<0.05; Table 1). The high doses of orientin or vitexin were not significantly different regarding changes in malondialdehyde content. However, the same doses of orientin or vitexin had similar effects on decreasing lipofuscin content. Compared with vitamin E, all orientin- or vitexin-treated groups significantly decreased the content of malondialdehyde in tissue and lipofuscin in the brain (P<0.05). The high doses of orientin or vitexin were not significantly different than vitamin E (Tables 1, 4).

Table 2 Effects of orientin and vitexin on T-AOC (U/mL), SOD (U/mL), CAT (U/mL), and GSH-PX (μM) levels in the serum of mice following D-galactose-induced aging

Table 3 Effects of orientin and vitexin on superoxide dismutase (U/mg) and catalase (U/mg) in various tissues of mice following D-galactose-induced aging

Table 4 Effects of orientin and vitexin on glutathione peroxidase (μM) and malondialdehyde (nmol/mL) in various tissues of mice following D-galactose-induced aging

Table 5 Effects of orientin and vitexin on Na+-K+-ATPase (U/mg) and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase (U/mg) levels in various tissues of mice following D-galactose-induced aging

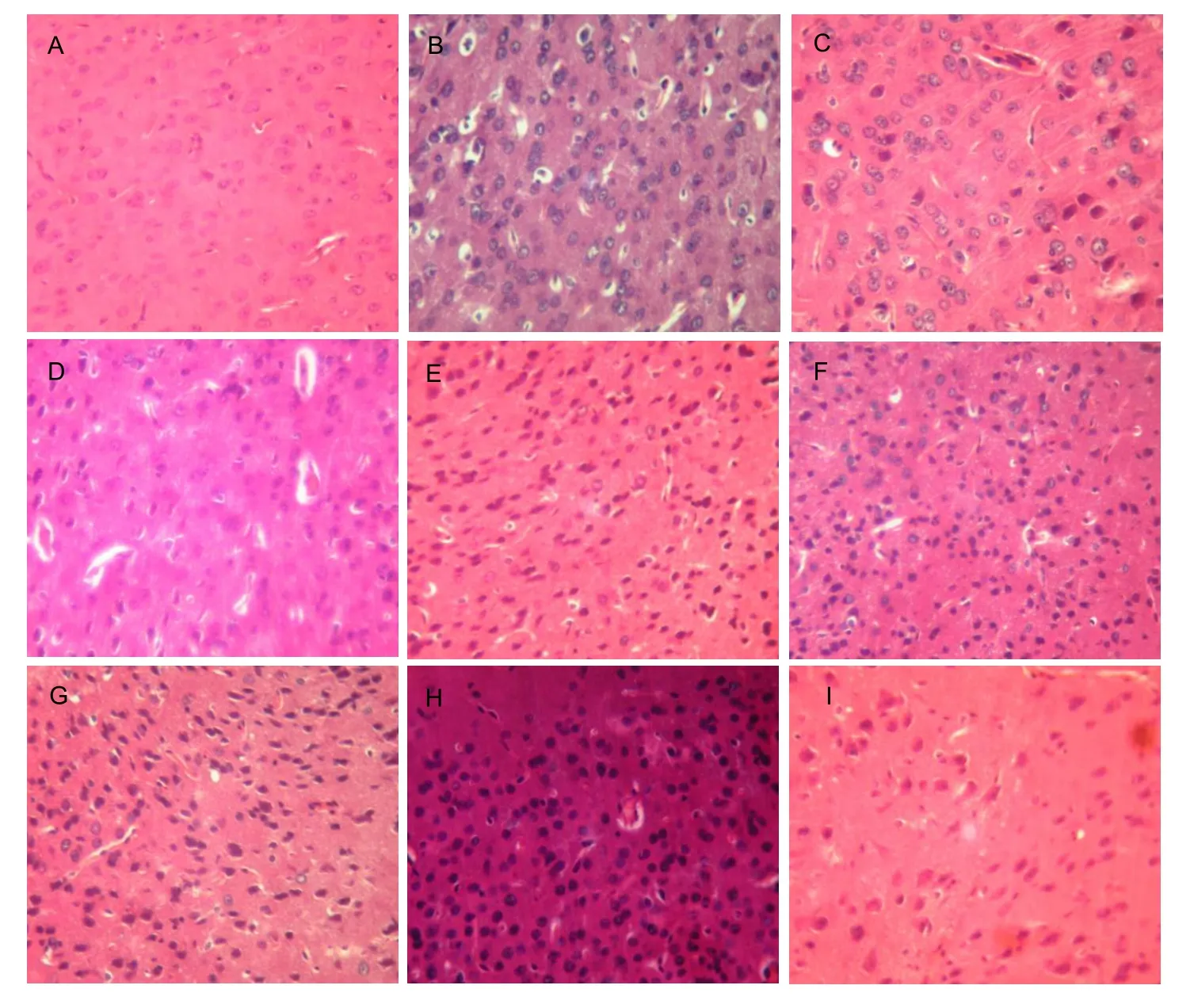

Orientin and vitexin improved the histopathological changes and microstructure of D-galactose-aged mice

Under the light microscope, the fewer brain cells, disordered ranking, reduced cell sizes, nuclear shape changes, and vacuolar degeneration were visible in the mice in the model group compared with those in the control group. Compared with the mice in the model group, each group treated with orientin, vitexin, or vitamin E had apparent improvements in the number and arrangement of brain cells, which were not significantly different among the groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Effects of orientin and vitexin on pathological changes in the brains of D-galactose-aged mice (hematoxylin-eosin staining,×400).

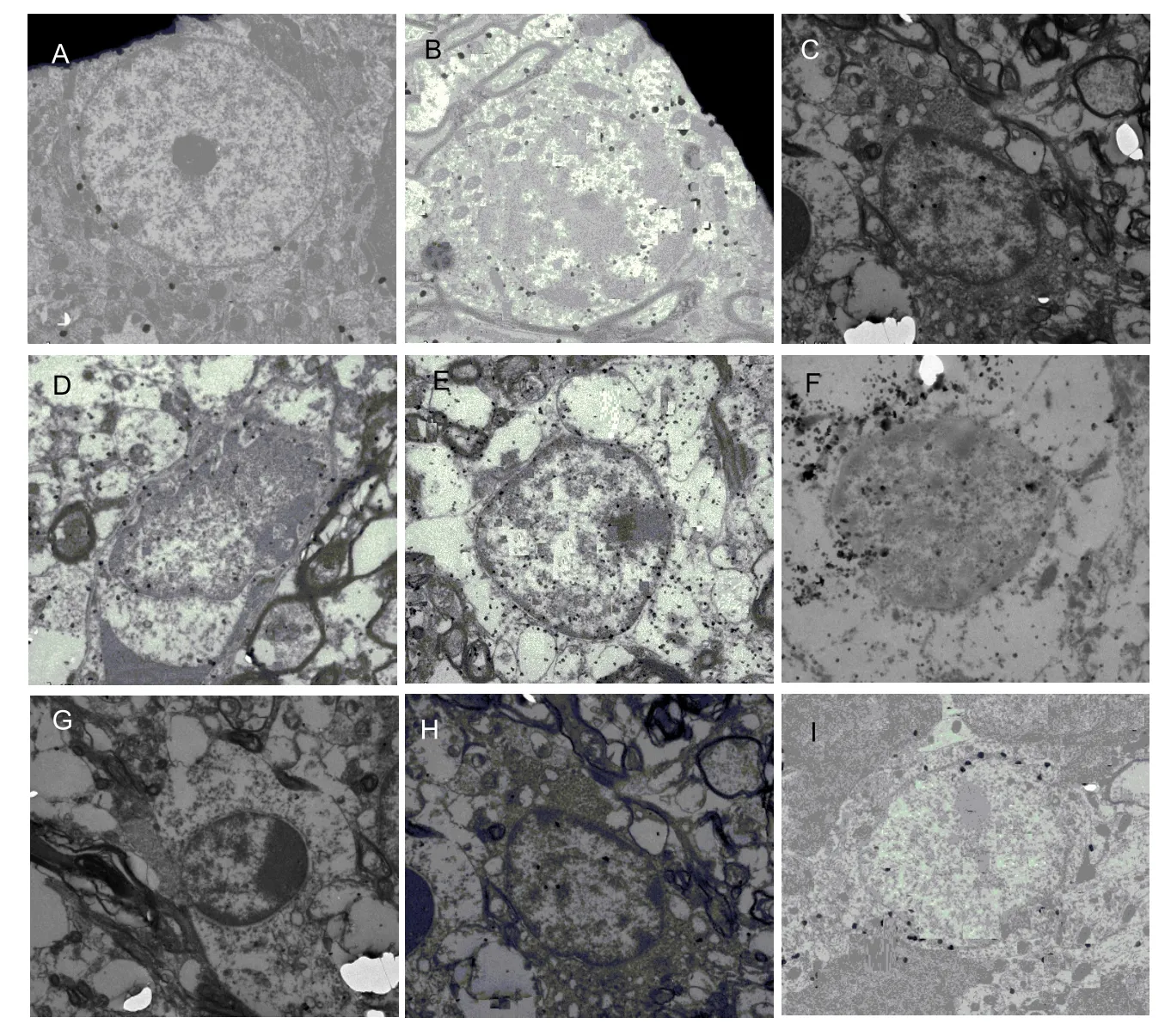

Under the transmission electron microscope, the ultrastructure of the brain cells in the mice in the control group exhibited clearer neuronal structures and more mitochondria than in those in the model group. Compared with the mice in the control group, the number of mitochondria was higher in the mice in the model group, with extended or vacuolar mitochondria and cristae vague. Their mitochondria were swollen and exhibited vacuolization. Compared with the mice in the model group, the ultrastructure of the mice in the treated groups was significantly better, especially at the high and medium doses as well as in the vitamin E group. These treatments can clearly improve corpuscular ultrastructure, up to the normal level (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Evidence of the successful establishment of an aging model

The aging model caused by subacute D-galactose is based on sugar metabolic disorder of inner cells, leading to eventual destruction of the antioxidant defense system of the body, free radical accumulation, rising lipid peroxide and lipofuscin, and eventual aging-like changes[37]. Continued administration of D-galactose for 6–8 weeks produces aged animals, whose physical characteristics are equivalent to mice at two years of age. This method was gradually adopted for use in studies of aging mechanisms and diseases and antioxidant drugs[38].

In these experiments, the aged condition of the mice caused by long-term administration of large amounts of D-galactose were assessed through measuring antioxidase changes, ion transport capacities of cell membrane, the weight of the brain, the accumulation of lipofuscin in the brain, and the morphology of the brain tissue. As previously described[39], this aging model has been validated, which allows for the rigorous and reliable study of the anti-aging effects of orientin and vitexin.

Figure 4 Effects of orientin and vitexin on the ultrastructure of brain tissue in D-galactose-aged mice (transmission electron microscope,×15 000).

Effects of orientin and vitexin on antioxidase activity in D-galactose-aged mice

Total antioxidant capacity has an important role in the defense system of the body, which mainly maintains the dynamic balance of active oxygen free radicals in the inner environment, clears high density active oxygen free radicals, and makes the body relatively stable. It can delegate the changes in the antioxidase system and nonenzyme system[40]. Therefore the determination of the total antioxidant capacity of the body is very important.

Superoxide dismutase is an important organic enzyme for clearing inner superoxide anion free radicals, and can catalyze disproportional reactions of superoxide anion free radicals to produce H2O2with a lower potential for cellular damage. Catalase and glutathione peroxidase can generate H2O2from water and oxygen, reduce or block lipid peroxidation, protect the body from hydrogen peroxide, delay cellular aging, and prevent free radicals from causing disease[41].

Our experimental results show that orientin or vitexin at each dose can improve the total antioxidant capacity of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in the serum, brain, liver, and kidneys of aged mice. These effects were significantly different compared with the model group. This is evidence that orientin and vitexin may increase antioxidant enzyme activity, remove excessive oxygen free radicals, and reduce or stop the destruction of cells and tissues, thus protecting the normal function of cells and tissue and delaying the aging process induced by D-galactose. These findings are consistent with the literature[42-43].

Effects of orientin and vitexin on ATP enzyme levels in D-galactose-aged mice

The function of Na+-K+-ATP depends on the existence of lipid membranes and normal membrane liquidity; the adjustment of enzyme activity gives necessary vitality to cells. The reduced activity of Na+-K+-ATP will affect the whole functioning of cells[44].

Ca2+-Mg2+-ATP is an important and ubiquitous membrane-bound enzyme. It allows intracellular Ca2+escape from the cell to maintain a relatively low intracellular Ca2+concentration[45]. The reduced activity of Ca2+-Mg2+-ATP leads to higher intracellular Ca2+concentrations[46], which can lead to increased membrane permeability and eventually to severe cycling in neurons[47].

The present study showed that orientin or vitexin at each dose improved the antioxidant enzyme levels of Na+-K+-ATP and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATP in mice aged by D-galactose, and these levels were significantly different compared with those in the mice in the model group. These experimental findings imply that orientin and vitexin can protect neurons by maintaining the stability of cell membranes, protecting the functions of cell membranes, and reducing neuronal intracellular Ca2+concentrations. These results are consistent with those previously described[48].

Effects of orientin and vitexin on malondialdehyde content in tissue, lipofuscin content in the brain, and brain weights in D-galactose-aged mice

Lipid peroxide is the main means for oxygen radicals to induce cell damage, through which malondialdehyde can connect with proteins and nucleic acids, and cause denaturation and even inactivation and decrease tissue elasticity. Conjugates having abnormal hydrogen bond cannot be dismantled as they are subsumed by lysosomes and accumulate in lipofuscin. Lipofuscin is deposited largely in cells, which leads to cell metabolic disorders, thus causing cell atrophy and apoptosis[49]. As far as we know, lipofuscin levels are an index of aging[50]. Aging is an inevitable result of the body's metabolic processes. Brain aging is the largest factor in the degeneration of various organs[51].

Our experimental results show that orientin and vitexin reduce the amount of malondialdehyde in the brain, liver, and kidneys and the content of lipofuscin in the brain, and improve the brain weights of aged mice. These effects were significant in comparison with the mice in the model group. This indicates that orientin and vitexin decrease the accumulation of lipofuscin in brain cells, maintain normal metabolism in nerve cells, prevent or alleviate atrophy in nerve cells, and increase the brain weight of aged mice by stopping lipid peroxidation caused by oxygen free radicals, reducing the amount of malondialdehyde, decreasing cross-linking reaction products produced by contact between malondialdehyde and proteins or nucleic acids, reducing the production of lipofuscin, and finally reducing the accumulation of lipofuscin in the neurons of aged mice. These results are consistent with the literature[42-43,48].

Effects of orientin and vitexin on brain morphology in D-galactose-aged mice

The morphology observations showed that compared with the mice in the model group, the number of cells in brain tissue was higher in the mice in each treated group, and the cell structure and nuclear membranes of the hippocampus recovered gradually, and the nuclear quality was better. This implied that orientin and vitexin can delay aging by maintaining normal cell structures, reducing the aging of brain nerve cells, and thus allowing them to function normally, which could be the mechanism for its anti-aging effects. These results are consistent with the literature[52-53].

In summary, orientin and vitexin improve antioxidant activity in D-galactose-aged mice, and their effects were not different from those of vitamin E. The antioxidant effects of orientin were better than those of vitexin. This is in line with the view that antioxidant activity is best when there is an O-phenolic hydroxyl in the B ring of the flavonoid rather than a phenolic hydroxyl[54].

MATERlALS AND METHODS

Design

A randomized and controlled animal experiment.

Time and setting

The experiment was performed at the Laboratory Center of Pharmacy, Hebei North University, China between June 2010 and June 2011.

Materials

Animals

Healthy Kunming mice of a clean grade, aged 6–8 weeks, half female and half male, and weighing 20±2 g were provided by the Animal Center of Hebei North University (certification No. SCXK (Ji) 2004-0001). All mice were housed in several cages at 23°C under a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 40% humidity, with fresh air and ventilation, and were allowed free access to food and water. The protocols were conducted in accordance with theGuidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, formulated by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China[55].

Drugs

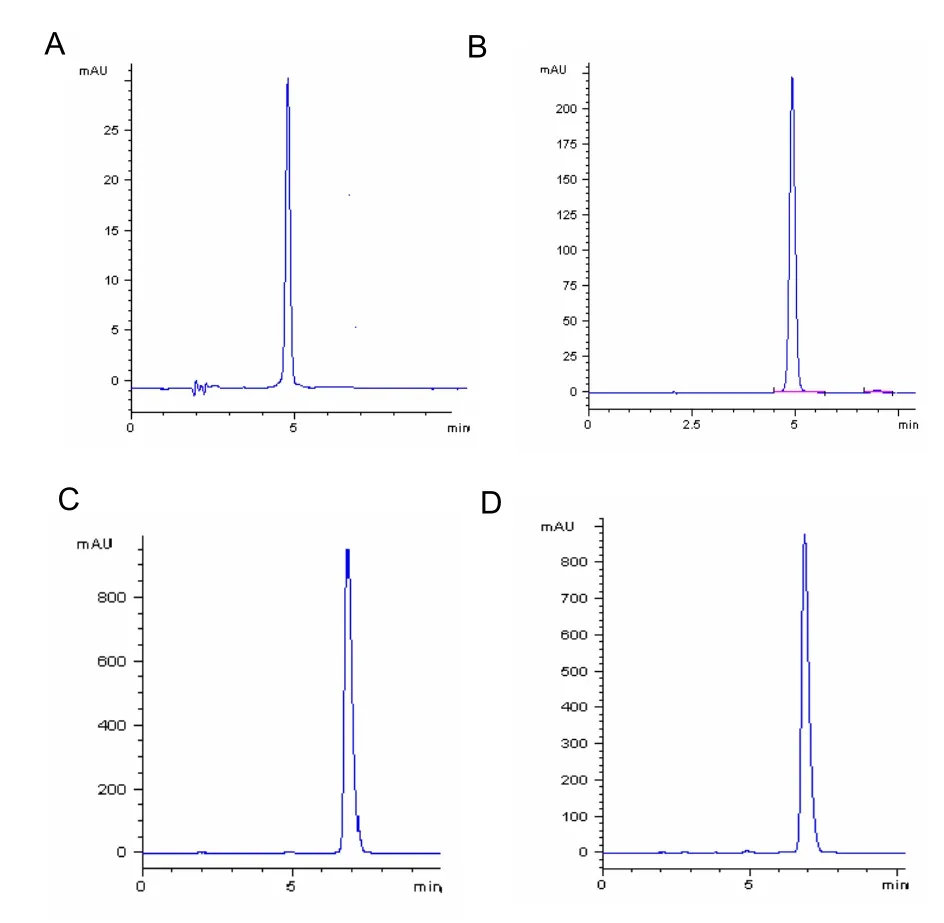

WildTrollius chinensiswas identified by Professor Shulan Ma who works in the Institute of Materia Medica of Hebei North University, China. Dried flowers ofTrollius chinensisBunge were collected from Guyuan, Zhangjiakou city, Hebei Province, China. Orientin and vitexin were prepared according to a reference[22]. First, a high performance liquid chromatography method was developed for the determination of the purity of orientin and vitexin. The column was a Hypersil BDS C18 (4.6 mm×150 mm, 5 μm) column using an acetonitrile: acetic acid (15:85) solution as the mobile phase and a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The column temperature was set to 30°C. The detection wavelength was 340 nm. Second, a preparative high performance liquid chromatography method was established for purifying orientin and vitexin. The column was a ZORBAX SB-C18 (21.2 mm×250 mm, 7 μm) column using an acetonitrile:acetic acid (15:85) solution as the mobile phase and a flow rate of 20 mL/min. The column temperature was set to 25°C. The detection wavelength was 340 nm. A fraction was collected based on the peak, with a minimum threshold of 2.2. Both nuclear magnetic resonance and high performance liquid chromatography were used for the structural and quantitative analysis of orientin and vitexin. The purities of orientin and vitexin were 98.9% and 98.6%, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Chromatographic analysis of orientin and vitexin.

Methods

Establishment of the aging model

In our subacute aging method[56], each animal was intraperitoneally injected with D-galactose (Shanghai Chemistry Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 200 mg/kg per day for 8 weeks. The mice in the control group were injected with 0.1 mL of physiological brine for 8 weeks. The amount administered was adjusted to the weight of each mouse. At the end of the 8thweek, total antioxidant capacity and superoxide dismutase and malondialdehyde levels in the mice in the model group were significantly different compared with those in the mice in the normal group. Accordingly, we deemed the model successfully established[57].

Administration

The dose administered was calculated according to the ratio of mouse to the human body surface area. All drugs were delivered by intragastric administration every morning from the 9thweek. The mice in the vitamin E group received 20 mg/kg of vitamin E per day. The mice in the control and model groups received N-dimethylformamide:tween-80:normal saline (1:1:20). For 8 weeks, the mice in the high-, medium-, and low-dose orientin or vitexin groups received were given 40, 20, or 10 mg/kg per day, respectively, of each drug dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide:tween-80:normal saline (1:1:20).

General observation

We observed the general conditions of the mice, such as their ingestion of food and water, body weights, activity, fur color, and fur glossiness.

Measurement of mouse brain weights

Under ether anesthesia, the head of each mouse was cut. We accurately measured the whole brain weight of each mouse following freezing using an electronic balance (Sartorius, Gottingen, Germany).

Measurement of antioxidant enzyme system in the blood serum of mice

Ten mice in each group were observed, and a 1 mL blood sample was collected from each mouse. Their heads were cut. Blood was extracted and centrifuged at 4 000 r/min for 10 minutes. Then, we tested the total antioxidant capacity, and the superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase levels according to instructions provided with the assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Co., Ltd., Jiangsu Province, China)[52,58].

Measurement of antioxidant enzyme system and malondialdehyde content in the mouse brain, liver, and kidneys

We accurately measured the mouse brain, liver, and kidneys, by making a 10% tissue homogenate using normal saline. The specimen was centrifuged at 8 000 r/min for 10 minutes. Then, the levels of superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and malondialdehyde were determined according to instructions provided with the assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Co., Ltd.)[52,58].

Measurement of ATPase levels in mouse brain, liver, and kidneys

We accurately measured the mouse brain, liver, and kidneys, by making a 10% tissue homogenate using normal saline, and diluting a 99-fold volume of normal saline into a 0.1% tissue homogenate. 0.1 mL of the 0.1% tissue homogenate was collected. At the same time, Coomassie Brilliant Blue (batch number: 20100918; Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Co., Ltd.) was applied to determine the tissue protein levels and levels of Na+-K+-ATPase and Ca2+-Mg2+-ATPase[52].

Determination of lipofuscin levels in the mouse brain

After the mouse heads were cut, brain tissues were immersed in normal saline and the surface blood was absorbed by filter paper. A mixture of chloroform and carbinol (v:v=2:1) was added using to a 20:1 ratio to body weight. This provided a 10% tissue homogenate, which was added to the same volume of distilled water and fully shaken for 3 minutes. The sample was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3 000 r/min. The chloroform layer was absorbed and 5 mL of chloroform was added. We measured fluorescence intensity by a fluorescence spectrophotometer (at excitation wavelength 360 nm and emission wavelength 420 nm, slit 10 nm; Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence intensity of a standard solution of quinine sulfate (1 μg/mL) was defined as 50, to calculate the micrograms of each fluorescent substance in each gram of cerebral cortex tissue, which is the amount of lipofuscin[59].

Brain morphology in mice

After mice were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (0.3 mL/100 g), the thoracic cavity was opened and the abdominal aorta was closed. This was followed by catheterization through the left ventricle and perfusion of 100–150 mL of normal saline. After the blood was rapidly rinsed, brain tissue was fixed with PBS (pH 7.2–7.4) containing 4% paraformaldehyde. The head was cut and the brain tissue was harvested, and 0.1 cm sagittal slices were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After fixing, the specimen was dehydrated with gradient alcohol for hematoxylin-eosin staining. Pathological changes in the brain tissue were observed under the light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan; type CX21,×40).

Using the same isolation methods, the hippocampus of each mouse was also harvested[52], and then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The ultramicro-structure of nerve cells in hippocampus of mice was observed under the transmission electron microscope (× 15 000, 120 kV Transmission Electron, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as mean±SD, and were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Intergroup differences were compared using least significant differencet-tests. AP<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Funding:This project was supported by the Foundation of Zhangjiakou Science and Technology Committee, No. 0711046D-9 and No.11110015D.

Author contributions:Fang An and Guodong Yang conceived and designed the study, conducted the majority of the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. Jiaming Tian contributed to data collection and completed the statistical analyses. Shuhua Wang revised the manuscript, approved the final version to be published, and was responsible for funding.

Conflicts of interest:None declared.

Ethical approval:All animal experiments were approved by the Hebei North University Committee on Ethics in the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Author statements:The manuscript is original, has not been submitted to or is not under consideration by another publication, has not been previously published in any language or any form, including electronic, and contains no disclosure of confidential information or authorship/patent application disputations.

[1] Turnheim K. When drug therapy gets old: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38(8):843-853.

[2] Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;11(3):298-300.

[3] Harman D. Free radical theory of aging. Mutat Res. 1992; 275(3-6):257-266.

[4] Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, et al. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(1):44-84.

[5] Chang JY, Chang CY, Kuo CC, et al. Salvinal, a novel microtubule inhibitor isolated from Salvia miltiorrhizae Bunge (Danshen), with antimitotic activity in multidrugsensitive and -resistant human tumor cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65(1):77-84.

[6] Li LQ. The geographical distribution of subfamily Helleboroideae (Ranunculaceae). Zhiwu Fenlei Xuebao. 1995;33(6):535-537.

[7] Li YL, Ye SM, Wang LY, et al. Isolation and biological activity of proglobeflowery acid from Trollius chinensis Bunge. Jinan Daxue Xuebao: Ziran Kexue Ban. 2002; 23(1):124-126.

[8] Shen ZP. Traditional Chinese medicine pharmaceutical research and application of Trollius Chinensis. Shizhen Guoyi Guoyao. 2000;11(12):1110-1113.

[9] Liu ZY, Luo DQ. The chemical composition of the Trollius Chinensis. Zhongcaoyao. 2010;41(3):370-373.

[10] Wang RF, Yang XW, Ma CM, et al. Analysis of fatty acids from the flowers of Trollius chinensis. Zhongcaoyao. 2010;33(10):1579-1581.

[11] Huang WZ, Wang L, Duan JA. Study of the chemical ingredients of Trollius ledebouri Reichb. Zhongcaoyao. 2000;31(10):731-732.

[12] Wu XA, Zhao YM, Zhu J, et al. Acylated Flavone C-glycosides from Trollius ledebouri Reichb. Tianran Chanwu Yanjiu yu Kaifa. 2009;21(1):1-5.

[13] Wang RF, Yang XW, Ma CM, et al. Trollioside, a new compound from the flowers of Trollius chinensis. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2004;6(2):139-144.

[14] Zou JH, Yang J, Zhou L. Acylated flavone C-glycosides from Trollius ledebouri. J Nat Prod. 2004;67(4):664-667.

[15] Ren ZB, Zhang ZX, Zhou WL, et al. Studies on the bioactivity consituents Trollius Ledebourii. Zhongguo Xiandai Zhongyao. 2006;8(2):14-15.

[16] Zhou X, Fan GR, Wu YT. Study of the antioxidant activity in vitro of flavonoids and Indexes composition of Trollius ledebouri Reichb. Zhongyaocai. 2007;30(8):1000-1002.

[17] Su LJ, Tian H, Ma YL. Trollius chinensis Bunge ethanolextraction objects in experimental study of antiviral effect. Zhongcaoyao. 2007;38(7):1062-1064.

[18] Sun L, Liu F, Liu H, et al. The effects of Trollius flavonoids on human breast cancer cells. Zhongguo Laonian Xue Zazhi. 2009;29(5):1098-1099.

[19] Sun L, Cheng JZ, Luo Q, et al. Effects of Trollius flavonoids on proliferation of K562, HeLa, Ec-109,and NCI-H446 tumor cells. Zhengzhou Daxue Xuebao: Yixue Ban. 2009;44(5):61-63.

[20] Sun L, Luo Q, Zhang L, et al. Effects of Trollius flavonoids on growth and apoptosis of A549 cells. Zhongguo Laonian Xue Zazhi. 2011;31(1):82-83.

[21] Huang WZ, Liang X. Determination of two flavone glycosides in Trollius ledebourli by HPLC. Zhongguo Yaoxue Zazhi. 2000;35(10):658-659.

[22] Qu CH, Yan J, Tian JM, et al. Simultaneous determination of three Flavone glycoside in Trollius chinensis Bunge by HPLC. Zhongchengyao. 2010;32(3):162-164.

[23] Yan J, Qu CH, Tian JM, et al. Separation and purification of Orientin and Vitexin in Trollius chinensis Bunge by PHPLC. Zhongchengyao. 2011;33(4):655-658.

[24] Fu XC, Li SP, Wang MW. Determination of two flavone glycosides in Trollius ledebourli by HPLC. Zhongguo Yaoke Daxue Xuebao. 2006;37(6):539-543.

[25] Fu XC, Wang X, Zheng H, et al. Protective effects of orientin on myocardial ischemia and hypoxia in animal models. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2007;27(8): 1173-1175.

[26] Fu XC, Li SP, Wang XG, et al. Antithrombotic effect of Orientoside. Zhongguo Yaofang. 2006;17(17):1292-1293.

[27] Kim JH, Lee BC, Kim JH, et al. The isolation and antioxidative effects of vitexin from Acer palmatum. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28(2):195-202.

[28] Budzianowski J, Pakulski G, Robak J. Studies on antioxidative activity of some C-glycosylflavones. Pol J Pharmacol Pharm. 1991;43(5):395-401.

[29] Prabhakar MC, Bano H, Kumar I, et al. Pharmacological investigations on vitexin. Planta Med. 1981;43(4): 396-403.

[30] Zhu DX. Studis on isolation and anti-tumor effect mechanisms of Orientin and Vitexin from Trollious chinensis bunge. Shijiazhuang: Hebei Medical University. 2011.

[31] Yang GD, Rao N, Tian JM, et al. Studis on outside antioxidation of Orientin and Vitexin of Trollius chinensis Bunge. Shizhen Guoyi Guoyao. 2011;22(9):2172-2173.

[32] Yan J, Hu HN, Qu CH, et al. Studis on antioxidation of general flavone in Trollius Chinensis Bunge. Shizhen Guoyi Guoyao. 2010;22(9):386-387.

[33] Yan J, Shang AM, Wang SH, et al. Pharmacokinetics and tissues distribution of vitexin from Trollious chinensis in rabbits. Zhongchengyao. 2012;34(4):650-653.

[34] Chen FP, Qu CH, An F, et al. Distribution of orientin from Trollius Chinensis in tissue of rabbits. Hebei Keji Daxue Xuebao. 2012;33(1):36-39.

[35] Chang W. The structure-activity relationship and ROS related mechanism of anti-cancer effect of flavonids. Chongqing: Third Military Medical University. 2008.

[36] Wu XA, Qing F, Du MQ. The QSAR study on anti-inflammatory activities of C-glycosyflavones. Shizhen Guoyi Guoyao. 2012;23(3):632-633.

[37] Zhu YZ, Zhu HG. Establishment and measurement of D-galactose induced aging model. Fudan Xuebao: Yixue Ban. 2007;34(4):617-619.

[38] Buttke TM, Sandstrom PA. Oxidative stress as a mediator of apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1994;15(1):7-10.

[39] Liu Y, Cheng QZ, Peng CH, et al. Making senile model of D-galactose and evaluating the effects in mice. Wuhan Gongye Xueyuan Xuebao. 2009;28(1):32-36.

[40] Li Y, Yang SQ, Zhang J. Acute aging model induced by γ-ray irradiation. WeishengYanjiu. 2002;31(4):290-291.

[41] Sandhu SK, Kaur G. Alterations in oxidative stress scavenger system in aging rat brain and lymphocytes. Biogerontology. 2002;3(3):161-173.

[42] Li YL. Studies on the chemical constituents and activity of Saxifraga Tangutica Engl. Lanzhou: Lanzhou University of Technology. 2011.

[43] Zhang J. Study on purification and bioactivity of Gingko Flavonoid. Wuxi: Jiangnan University. 2010.

[44] Liang WY, Yang ZC, Huang YS. Calcium ion transport and cell metabolism regulation in mitochondria. Shengli Kexue Jinzhan. 2000;4(31):357-358.

[45] Zhang W, Zhang YS, Yao L, el at. Effect of Oncolyn on activities of ATPase and neurotrophic factors expression in aged mice. Weisheng Yanjiu. 2007;36(2):164-166.

[46] Wang XL, Li DC, Hou YC. The progress of research on relationship among the Radical, apoptosis and aging. Zhongguo Laonian Xue Zazhi. 1999;19(4):252-253.

[47] Germann I, Hagelauer D, Kelber O, et al. Antioxidative properties of the gastrointestinal phytopharmaceutical remedy STW 5 (Iberogast). Phytomedicine. 2006;13 Suppl 5:45-50.

[48] Ni AW. The extraction and antioxidant function evaluation of portulaca total flavone. Yangzhou: Yangzhou University. 2010.

[49] Wei XL, Zhang YX. Progresses in studies on animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Zhongguo Yaoli Xue Tongbao. 2000;16(4):372-376.

[50] Suganuma H, Hirano T, Inakuma T. Amelioratory effect of dietary ingestion with red bell pepper on learning impairment in senescence-accelerated mice (SAMP8). J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 1999;45(1):143-149.

[51] Qu ZQ, Xie ZG, Wang NP, et al. Experimental studies on anti-aging actions of total Saponins of Radix Notoginseng. Guangzhou Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2005;22(2): 130-133.

[52] Zhao XY. Experimental study on erzhi pill on capability and mechanism of anti-oxidation on aging rats induced by D-galactose. Harbin: Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine. 2007.

[53] Chen YQ, Wang AM, Tian M. Effects of Pueraria isoflavone on learning and memory and changing of neurons morphology in hippocampi of aging rats. Yixue Lilun yu Shijian. 2011;24(20):2405-2407.

[54] Liu LH, Wan XC, Li DX. Research progress on structure-activity relationships of the antioxidant activity of Flavonoids. Anhui Nongye Daxue Xuebao. 2002;29(3): 265-267.

[55] The Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 2006-09-30.

[56] Miao MS. Effect of Fructus Schisandrae polyglucose on senile model mice. Zhongguo Yiyao Xuebao. 2002;17(3): 187-189.

[57] Zhang D, Liu G, Shi J, et al. Coeloglossum viride var. bracteatum extract attenuates D-galactose and NaNO2induced memory impairment in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104(1-2):250-256.

[58] Chen G, Tang Y, Yang L, et al. Antioxidative effects of LSPC in brain tissue of senile mice induced by D-galactose. Zhongguo Yaoshi. 2009;12(8):1023-1025.

[59] Leutner S, Eckert A, Müller WE. ROS generation, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activities in the aging brain. J Neural Transm. 2001;108(8-9):955-967.

10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.33.001 [http://www.crter.org/nrr-2012-qkquanwen.html]

An F, Yang GD, Tian JM, Wang SH. Antioxidant effects of the orientin and vitexin in Trollius chinensis Bunge in D-galactose-aged mice. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7(33):2565-2575.

Fang An★, Master, Professor, College of Pharmacy, Hebei North University, Zhangjiakou 075000, Hebei Province, China

Shuhua Wang, Master, Professor, College of Pharmacy, Hebei North University, Zhangjiakou 075000, Hebei Province, China shwang1988@yahoo.com.cn

2012-07-30

2012-10-20 (N20120529003/YJ)

(Edited by Bai J, Hu WX/Yang Y/Wang L)

- 中國神經(jīng)再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Electroacupuncture improves neuropathic pain Adenosine, adenosine 5’-triphosphate disodium and their receptors perhaps change simultaneously☆

- Underlying mechanism of protection from hypoxic injury seen with n-butanol extract of Potentilla anserine L. in hippocampal neurons***☆

- Shuanghuanglian injection downregulates nuclear factor-kappa B expression in mice with viral encephalitis*★

- Acupuncture inhibits cue-induced heroin craving and brain activation**★

- Puerarin prevents high glucose-induced apoptosis of Schwann cells by inhibiting oxidative stress*★

- Heat-sensitive moxibustion attenuates the inflammation after focal cerebral ischemia/ reperfusion injury*☆