Hepatocyte differentiation of human fibroblasts from cirrhotic liver in vitro and in vivo

Yu-Ling Sun, Sheng-Yong Yin, Lin Zhou, Hai-Yang Xie, Feng Zhang, Li-Ming Wu and Shu-Sen Zheng

Hangzhou, China

Hepatocyte differentiation of human fibroblasts from cirrhotic liver in vitro and in vivo

Yu-Ling Sun, Sheng-Yong Yin, Lin Zhou, Hai-Yang Xie, Feng Zhang, Li-Ming Wu and Shu-Sen Zheng

Hangzhou, China

BACKGROUND:Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and fibroblasts have intimate relationships, and the phenotypic homology between fibroblasts and MSCs has been recently described. The aim of this study was to investigate the hepatic differentiating potential of human fibroblasts in cirrhotic liver.

METHODS:The phenotypes of fibroblasts in cirrhotic liver were labeled by biological methods. After that, the differentiation potential of these fibroblastsin vitrowas characterized in terms of liver-specific gene and protein expression. Finally, an animal model of hepatocyte regeneration in severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice was created by retrorsine injection and partial hepatectomy, and the expression of human hepatocyte proteins in SCID mouse livers was checked by immunohistochemical analysis after fibroblast administration.

RESULTS:Surface immunophenotyping revealed that a minority of fibroblasts expressed markers of MSCs and hepatic epithelial cytokeratins as well as alpha-smooth muscle actin, but homogeneously expressed vimentin, desmin, prolyl 4-hydroxylase and fibronectin. These fibroblasts presented the characteristics of hepatocytesin vitroand differentiated directly into functional hepatocytes in the liver of hepatectomized SCID mice.

CONCLUSIONS:This study demonstrated that fibroblasts in cirrhotic liver have the potential to differentiate into hepatocyte-like cellsin vitroandin vivo. Our findings infer that hepatic differentiation of fibroblasts may serve as a new target for reversion of liver fibrosis and a cell source for tissue engineering.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 55-63)

fibroblasts; hepatocytes; mesenchymal-epithelial transition

Introduction

The differentiation of stem cells into the hepatic lineage is a recently-developed model of parenchymal liver cells, which is of great importance in toxicology and bioartificial liver research.[1,2]Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) responsible for self-repair and regeneration exist in various organs of the human body.[3-5]A population of stem cells has been successfully isolated and characterized in the fetal and normal adult human liver.[6,7]In special inducible conditions, bone marrow MSCs and hepatic progenitor cells from human umbilical cord blood differentiate into functional hepatocytes through mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET).[8-11]

It is verified that MSCs have intimate relationships with fibroblasts,[12,13]and that it is difficult to discriminate fibroblasts from MSCs based on phenotype (morphology and specific protein markers) or growth capacity.[14-16]Comparison of their characteristics demonstrates that they are probably different functional states of the same cells. Previous reports[17-19]also show that fibroblasts possess the ability of further differentiation. These observations support the hypothesis that fibroblasts may be transitional cells in a stem cell lineage that eventually gives rise to mature cells.

Portal fibroblasts and circulating mesenchymalcells are important sources of matrix proteins in liver fibrosis. In this fibrogenic process, epithelial cells undergo an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), similarly assuming a fibrogenic phenotype and contributing to pulmonary and liver fibrosis.[20-22]However, accumulating evidence confirms that EMT can be reversed in human bronchial fibroblasts and the NIH3T3 cell line, and even myofibroblasts in the liver.[23-26]

After exposure to a specific differentiation cocktail, human skin fibroblasts become morphologic and functional hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo, demonstrating MET.[27]These studies on MSCs and fibroblasts remind us that the fibroblasts in the cirrhotic liver possess the characteristics of stem cells. The aim of this study was to investigate the hepatic differentiation potential of human hepatic fibroblasts. We hypothesized that fibroblasts in cirrhotic liver are capable of proliferating and differentiating into functional hepatocyte-like cells in vitro and in vivo. In this study, we characterized a proliferating cell type expressing the MSC phenotype and stem cellassociated markers from human adult cirrhotic liver.

Methods

Liver tissue samples

Four liver tissue samples were obtained from surgical specimens from patients undergoing liver transplantation for HBV-associated cirrhotic liver dysfunction. Tissues were removed without tumors and found to be histologically free of neoplastic involvement. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Experimentation at our institution and all samples were taken after the patients had given informed consent.

Fibroblast preparation

Liver fibroblasts were isolated by enzymatic digestion as described previously.[24]Briefly, tissue samples obtained within 1 hour of resection were separated into fragments of 0.5-2 mm3, and washed with Williams' E medium (Sigma-Aldrich) three times for 10 minutes. The tissues were digested for 2 hours at 37 ℃ using collagenase (500 U/ml), hyaluronidase (30 U/ml) and DNAse (10 U/ml) (Sigma) in Williams' E medium. Cells were then collected by centrifugation at 500 g, washed twice, filtered through a 20-μm Nitex filter, slowly frozen to -80 ℃ in 7.5% DMSO, thawed, and plated onto 100-mm culture dishes (Costar, Acton, MA) precoated with 0.1% 400 μl rat-tail collagen at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2in Williams' E medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin/ streptomycin, 20 mmol HEPES, 20 mmol sodium pyruvate (Gibco), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Gibco), 20 ng/ml hepatocyte growth factor (Sigma), and 20 mU/ml insulin (Sigma). Medium with or without growth factors was changed twice a week. After reaching confluence, the cells were trypsinized and those which were not adherent within 25 minutes were removed.

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this study were: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-human CD34, CD45, CD73, CD44, albumin, and vimentin (BD Biosciences); anti-human prolyl 4-hydroxylase, hepHar-1 and albumin (Dako); CD133, c-kit, Thy-1, AFP, CK18, CK19, vimentin, desmin, fibronectin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Controls were rabbit or mouse IgG at equivalent concentrations.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC was performed to identify the expression of markers. Four-micrometer-thick formalin-fixed paraffinembedded sections were incubated with hydrogen peroxide (2.4 ml, 30%) in methanol (400 ml) to block endogenous peroxidases. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving in sodium citrate. Liver sections were treated with an avidin/biotin kit (X0590; Dako, Cambridgeshire, UK), blocked in serum (normal swine, goat, or rabbit serum diluted 1/25 in PBS; Dako) for 15 minutes, and then incubated in the primary antibody at an appropriate dilution for 35 minutes. A biotinylated secondary antibody was then applied for about 35 minutes.

Flow cytometry

Trypsinized cells (2×105) were suspended at a concentration of 0.5 to 1×103/μl in PBS and then incubated for 30 minutes at 4 ℃ with fluorescenceconjugated monoclonal antibodies. The cells were then washed and resuspended in Isoton (Becton Dickinson). After washing with 1 ml PBS and centrifuging for 5 minutes at 800 g, the cells were fixed in 250 μl Cellfix (BD Bioscience) and read on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Beckman, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) measurements

Immunofluorescence double staining was performed to visualize the co-expression of different markers. Cultured fibroblasts were fixed with 80% acetone for 20 minutes at -20 ℃, washed three times with PBS, andincubated for 2 hours with diluted primary antibodies at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with corresponding secondary antibodies. For each analysis, a negative control was performed by removal of the primary antibody from the protocol. Tissue sections were treated by IHC and then inoculated with different antibodies. All the images were processed with the Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software package.

Cytospins and immunocytochemistry (ICC)

Cells were harvested from cultures and cytospins were prepared by plating cells on glass slides. After 24 hours of culture in an incubator, cytospins were fixed with dehydrated alcohol/dimethylketone at 1∶1 for 20 minutes and then ICC analysis was performed. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Western blotting analysis

Cell lysates of proteins from different culture stages were subjected to 0.1% SDS-7.5% PAGE, and the separated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham). The various proteins were detected on immunoblots using different primary antibodies diluted with 0.05% Triton X-100 in Trisbuffered saline containing 1% gelatin, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were developed by ECL (Amersham) and blots were exposed to medical X-ray film. Cell lysates for positive controls were from HCC or cirrhotic liver tissue.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of hepatocyte-specific markers

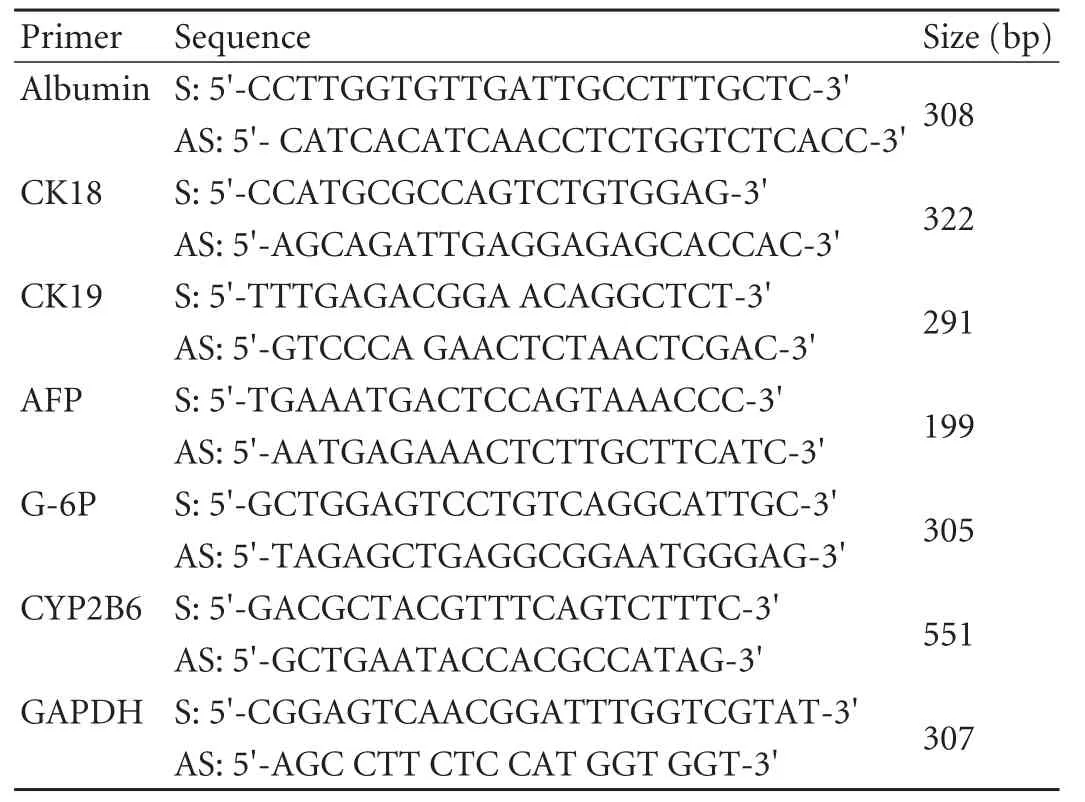

Total RNA was prepared from fibroblasts at different culture stages by the Trizol method with standard procedures. Briefly, cells were lysed, DNAse-treated, and subjected to RT prior to conventional PCR amplification using a hot-start protocol. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) cRNA from HCC tissue and other total RNA from cirrhotic liver tissue were used as positive controls. The primer pairs are listed in Table 1. The PCR conditions for CK18, CK19 and AFP were 94 ℃ for 10 minutes, 94 ℃for 30 seconds, 58 ℃ for 30 seconds, 72 ℃ for 1 minute, 35 cycles, 72 ℃ for 10 minutes. For Alb and G-6-P the conditions were as above but the annealing temperature was 62 ℃ and 40 cycles. The PCR conditions for CYP2B6 were 94 ℃ for 10 minutes, 94 ℃ for 30 seconds, 56 ℃for 30 seconds, 72 ℃ for 1 minute, 40 cycles, and 72 ℃for 10 minutes. The PCR conditions for GAPDH were 57 ℃ for annealing temperature with 28 cycles. PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gel.

Table 1. Primers used for RT-PCR analysis

Retrorsine administration, partial hepatectomy and cell transplantation

Severe combined immunodeficient mice were randomized into retrorsine treatment (n=36) and control (n=20) groups at the beginning of the experiment. All the animals in the retrorsine treatment group received two doses of retrorsine (30 mg/kg i.p.) two weeks apart (at 6 and 8 weeks of age). The retrorsine working solution was prepared as described.[28]Retrorsine (12, 8-dihydr oxysenecionan-11, 16-dione; b-Longilobine, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to distilled water at 10 mg/ml and titrated to pH 2.5 with 1 N HCl to completely dissolve the solid. Subsequently, the solution was neutralized using 1 N NaOH, and NaCl was added for a final concentration of 6 mg/ml retrorsine and 150 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.0. The working solution was administered immediately after preparation. Five weeks after the second retrorsine treatment, a two-thirds partial hepatectomy (PH) was performed on the experimental group and a control group of similar age (13 weeks old) as described.[29]The mortality in retrorsine-exposed mice after PH was higher (40%) than that of the controls (24%), likely due to the effects of retrorsine toxicity. In the 31 surviving mice, a total of 1×107fibroblasts (in 0.1 ml PBS, isolated from different tissue samples and at their first or second passage) were infused into the liver via the portal vein under anesthesia. Six mice died after this procedure. Fifteen control mice were subjected only to physiological saline injection and PH. They were sacrificed and liver samples were harvested 2, 4 and 8 weeks after cell transplantation. Liver tissue was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed routinely for paraffin-embedded sections. All animals received humane care, and this study was conducted underthe protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Results

Immunophenotypes of human cirrhotic liver fibroblasts

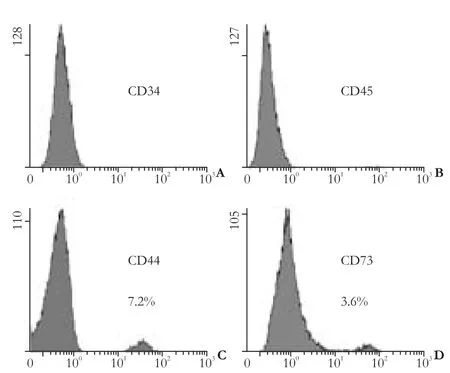

Fig. 1. Cytometric phenotype of hepatic fibroblasts (cells from passages 1 or 2).

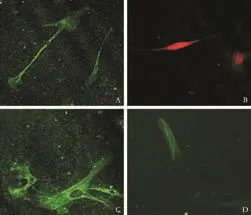

Fig. 2. Phenotypes of hepatic fibroblasts (cells from passages 1 or 2) identified by LSCM. Small subpopulations of Thy-1 (A), c-kit (B) and CD133-positive (C) and α-SMA-positive (D) cells were identified by immunofluorescent staining (original magnification ×40).

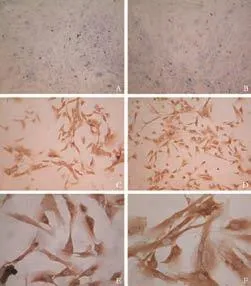

Flow cytometric analysis revealed that very few fibroblasts expressed CD73 and CD44, which are markers specifically exposed on MSCs. The hemopoietic stem cell markers, CD34 and CD45, were not found (Fig. 1). A small subpopulation of Thy-1 (≤11%), c-kit (≤5%) and CD133 (≤3%)-positive cells was also found (Fig. 2A-C). Further evaluation of cystoskeletal and extracellular matrix elements by immunofluorescent staining showed that a few cells stained positively for the myofibroblast marker α-SMA in microfilaments (≤4%) (Fig. 2D). About 5% CK18 and CK19-positive cells were identified (Fig. 3A, B). In addition, these fibroblasts homogeneously expressed vimentin, desmin, collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase and fibronectin (Fig. 3C-F). No albumin expression was found. The results are summarized in Table 2.

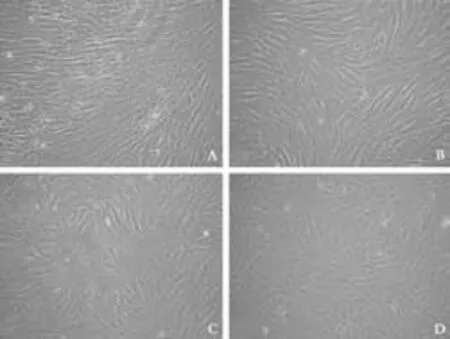

Cell morphology during the culture period

Under specific conditions, fibroblasts gradually progressed toward the polygonal morphology of hepatocytes in a time-dependent manner accompanied by the expression of different hepatic lineage markers. The fibroblasts at the beginning of culture showed typical spindle-shaped morphology (Fig. 4A). No matter whether growth factors were present or not, the morphology of fibroblasts was lost and the cellsdeveloped a broadened, flattened morphology after 2 weeks of induction (Fig. 4B). Four weeks later, retraction of the elongated ends occurred (Fig. 4C) and then the cuboidal morphology of hepatocytes developed with time (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, cell density played a significant role in hepatic differentiation. Optimal cell density was found to be 0.9 to 1.4×104cells/cm2. Inspection under a microscope indicated that hepatocyte-like cells were located in the center of cell clusters, while diffused cells failed to adopt the cuboidal characteristic of hepatocytes, even though they expressed albumin on immunofluorescence analysis. After long-term culture, the hepatocyte-like morphology further matured and abundant granules were observed in the cytoplasm.

Fig. 3. Phenotypes of hepatic fibroblasts (cells used from passages 1 or 2) identified by ICC. A few cells stained for epithelial markers CK18 (A) and CK19 (B). All fibroblasts homogeneously expressed vimentin (C), desmin (D), prolyl 4-hydroxylase (E) and fibronectin (F) (original magnification: A, B ×10; C, D ×20; E, F ×40).

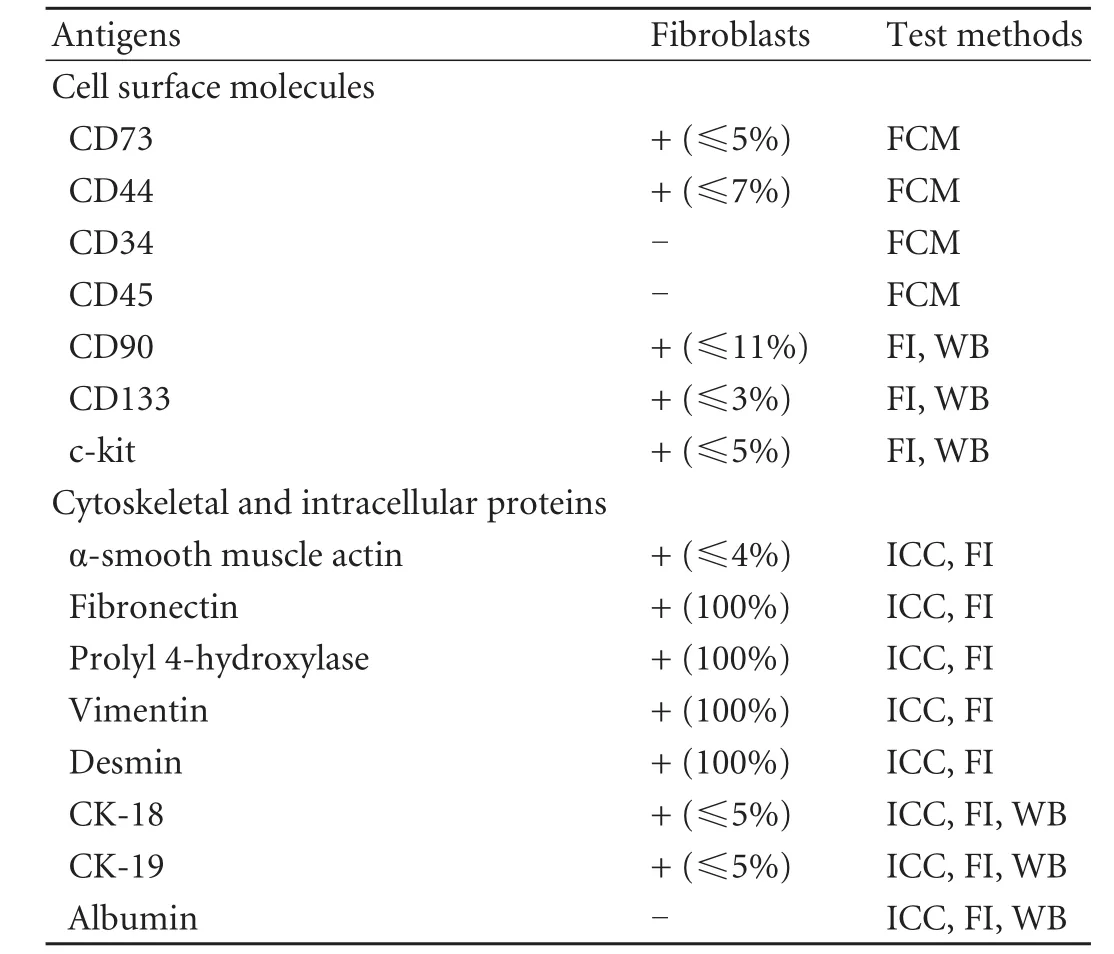

Table 2. Summary of the phenotypic characteristics of fibroblasts

Fig. 4. Morphological changes of fibroblasts from cirrhotic liver to differentiated hepatocyte-like cells. A: Undifferentiated fibroblasts show typical spindle-shaped morphology; B: The morphology of fibroblasts was lost and cells developed a broadened, flattened morphology after 2 weeks in culture; C: Retraction of elongated ends was observed 4 weeks post-induction; D: Cuboidal morphology of hepatocytes developed with time after 6 weeks in culture (original magnification: A ×4; B-D ×10).

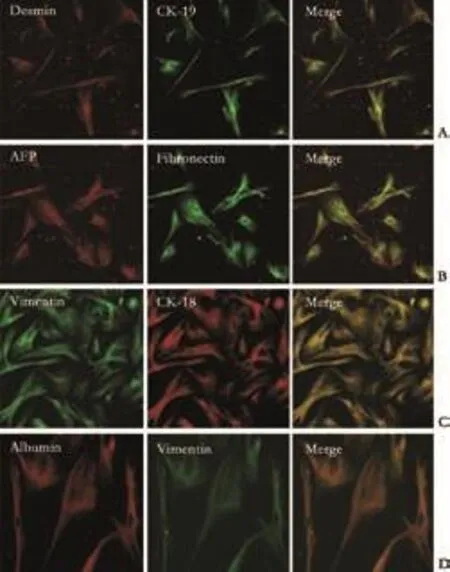

Co-expression of cystoskeletal and extracellular matrix elements and hepatic lineage markers

Fig. 5. Immunofluorescence double staining of cystoskeletal elements and hepatic lineage markers (cells after 30 days in culture). Co-expression of cytoskeletal elements and hepatic lineage markers was identified and the morphology of cultured fibroblasts showed major changes, but they still retained some characteristics of fibroblasts such as the presence of intermediate filaments (original magnification: A-C ×10; D ×20).

In order to identify the co-expression of cystoskeletal and extracellular matrix proteins as well as hepatic lineage markers, we performed double labeling by LSCM. The cells typically looked like fibroblasts and homogeneously expressed fibroblast markers (vimentin, desmin, fibronectin and collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylase).At the beginning of cell culture, 5% of these cells were identified as CK18- and CK19-positive. After 15 days, almost all the fibroblasts expressed the hepatic lineage markers AFP and CK18; Alb was also expressed after 30 days of induction. After long-term induction, the fibroblasts retracted and gradually took on the shape of hepatocytes, but these cells still possessed some characteristics of fibroblasts such as the expression of proteins of intermediate filaments. The results are shown in Fig. 5 and demonstrate the cell characteristics after 30 days in culture.

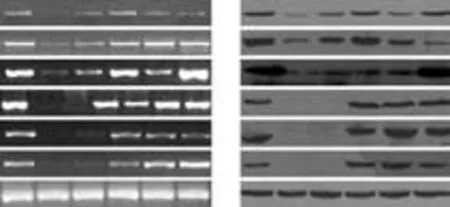

Expression profiles of hepatic lineage markers

The results of PCR amplification of cDNA and Western blotting of hepatic proteins from cultured cells are shown in Fig. 6. RT-PCR analysis showed the expression of AFP, CK19 and CK18 at almost all time points and this increased with time, while Alb, G-6P and CYP2B6, late marker genes of hepatocytes were detected by day 35. These markers were still expressed after cells had been cultured for 120 days. The cultured cells displayed persistent expression of the mesodermal marker vimentin and immunofluorescent analysis also demonstrated Alb and vimentin expression simultaneously. Taken together, the expression profiles showed that various stages of hepatocyte lineage, including both hepatic progenitor cells and mature hepatocytes, were present in our cultured fibroblasts. It is reasonable to consider that fibroblasts differentiated into mature hepatocytes in our primary culture system.

Hepatic fibroblasts as functional hepatocytes in the liver of recipient mice

Fig. 6. Hepatic differentiation of fibroblasts under culture conditions detected by RT-PCR and Western blotting. A: Cultured fibroblasts expressed hepatic marker genes after 10, 25, 35, 45 and 60 days in culture. B: Cultured fibroblasts expressed hepatic lineage proteins after 10, 25, 35, 45 and 60 days in culture. Positive controls with AFP were from HCC and others from cirrhotic liver.

To investigate whether human fibroblasts were able to engraft and differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells in vivo, cell transplantation was performed in liverinjured severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice. The engraftment and differentiation of liver fibroblasts in the liver of recipient SCID mice were analyzed at 2, 4, and 8 weeks after cell transplantation. At two weeks, the hepatic marker CK18 was observed by immunohistochemical staining. By the fourth week, markers of mature hepatocytes, anti-human albumin and hepPar-1, were seen in the samples. Like the results in vitro, liver sections from recipient mice also expressed the mesenchymal cell marker vimentin (Fig. 7). As generally observed in functionally differentiated hepatocytes, some of the Alb-producing cells derived from hepatic fibroblasts also showed a typical binucleated structure. RT-PCR and Western blotting also showed the same results in the liver of recipient mice (data not shown). These findings provided direct evidence that the fibroblasts engrafted in mouse liver differentiated into functionally mature hepatocytes. Cells with positive signals were observed in the recipient mice sacrificed at the fourth week after cell transplantation, whereas no signal was detected in the livers of the control mice. These cells clearly exhibited the morphology of liver parenchymal cells with large round nuclei and rich cytoplasm. Subsequent immunohistological analysis revealed that LSCM-positive cells were also positively stained for human Alb (data not shown).

Fig. 7. Hepatocyte differentiation of human cirrhotic fibroblasts in vivo. Images show immunohistochemical staining for human markers vimentin, hepPar-1, albumin and CK18. Analysis of SCID mouse liver revealed that fibroblasts engrafted as small clusters of cells presenting combined expression of the mesenchymal cell marker vimentin and the liver-specific markers hepPar-1, albumin and CK18. Positive and negative control staining for human and mouse liver were also performed (original magnification ×40).

Discussion

It is well accepted that tissue fibroblasts play a key role in growth factor secretion, matrix deposition and degradation, and therefore are important in many pathologic processes including liver fibrosis.[30]Recent studies[24,31]indicated that fibroblasts possess the characteristics of stem cells. The differentiation potential of such a population raises the question of whether fibroblasts within different tissues are responsible for the results observed. In this study, we reported for the first time that human hepatic fibroblasts possess a potential capacity for endodermal differentiation.

A study[24]demonstrated that bronchial fibroblasts, fetal lung fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived fibroblasts express MSC markers such as CD73, CD44 and CD90. In our study, only a minority of fibroblasts expressed the stem cell markers CD73, CD44 and CD90. This difference between the two studies is probably caused by different fibroblast purities and/or tissue specificity. CD133-positive cells were also noted in our study. Generally, CD133 is a marker of hematopoietic stem cells and their culture generates myofibroblasts in human liver undergoing tissue remodeling.[32,33]However, other studies[34-36]suggested that CD133 could be a marker for MSCs and a subpopulation is characterized by the co-expression of CD133 and CD34. These data inidcated that stem cells originating from bone marrow can be a source of fibrogenic cells in cirrhotic liver, and co-expression of CD133 and CD34 on MSCs possibly implies trans-differentiation between the hematopoietic stem cell pool and the MSC pool.

In the adult, the presence of fibroblasts could benefit epithelial homeostasis, regeneration and repair following tissue injury, and several fibrogenic populations participate in this process. Other than MSCs, EMT also provides fibroblasts that remodel pathological tissue. A subpopulation of mature hepatocytes can dedifferentiate and then demonstrate stem cell characteristics. They show high levels of vimentin expression through EMT, which means the generation of fibroblasts in liver fibrogenesis.[37-39]In our study, the expression of CK18 and CK19 in a few cells inferred that these cells might be experiencing a hepatocyte-to-fibroblast transition.

The frequency of cellular transitions is very low in the adult, and this reduced incidence could result from restrictive features of the microenvironment that stabilize adult cell phenotypes and prevent plastic behavior.[40]Nonetheless, in the long course of liver cirrhosis, a cytokine network established by mutual crosstalk between mesenchymal and epithelial cells is crucially involved in the tight control of cell proliferation and differentiation. The traditional oneway street of progressive commitment to differentiation may not be irreversible.[41]After kidney injury, interstitial cells might assume an immature phenotype, providing paracrine support for surrounding vessels and tubular epithelial cells, and finally differentiate into erythropoietin-producing fibroblasts,[23]indicating MET. EMT and MET are induced by environmental factors including extracellular matrix components, cell surface cytokines, and soluble cytokines.[40]In addition, whether the fibroblasts which experienced hepatic differentiation in the present study came from EMT was still unclear, although EMT occurs in liver fibrosis.[22]

Our data confirmed that fibroblasts from cirrhotic liver possessed hepatocyte differentiating potential invitroandin vivo. These cells were able to engraft and express hepatic markers such as AFP and albumin. Nonetheless, we were not sure if this phenomenon could occur in vivo in the process of reversal of liver fibrosis. In addition, our results also showed that the differentiated hepatocyte-like cells still retained some characteristics of fibroblasts, such as the expression of vimentin. Therefore, these induced hepatocyte-like cells may be in an unstable condition. Further study is needed to determine whether these cells differentiate back into fibroblasts under some circumstances. Taken together, these findings suggested that a substantial number of organ fibroblasts appear through a novel reversal in the direction of epithelial cell fate. As a general mechanism, this change highlights the potential plasticity of differentiated cells in adult tissues under pathologic conditions.[42]

During embryonic development, growth factors are associated with endodermal specification.[43,44]After partial hepatectomy, the blood level of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) increases greatly,[45]suggesting that HGF plays an important role in the early stages of hepatogenesis. With the induction of collagen type I-coated dishes and growth factors HGF and fibroblast growth factor-4, human skin fibroblasts differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells.[27]In addition, some studies also indicate that HGF induces early transition of Albnegative stem cells to Alb-positive hepatic precursors.[11,46]Another study demonstrated that HGF acts through different pathways to determine its complex effects on MSCs.[47]However, our data demonstrated that hepatic fibroblasts differentiated into hepatocyte-like cells without any growth factors except the collagen coating on dishes. The reasons for these discrepancies are: (a) our fibroblasts came from the liver and possessed sometissue specificity; (b) the fibroblasts in our study may have come from varied sources and they had hepatic cell line characteristics; or (c) the fibroblasts had already finished hepatic differentiation.

As for the extracellular matrix, some researchers agree that it is necessary for the differentiation of stem cells and precursors, but its effects are only supportive.[46]While our results confirmed the importance of the extracellular matrix by using rat-tail collagen in the process of hepatic differentiation. Nonetheless, the exact effect of collagen on fibroblast differentiation is under further investigation.

The differentiation potential of adult stem cells is thought to be limited to the tissue or germ layer of their origin. However, the differentiation of MSCs into functional hepatocytes raises a major challenge to this theory.[10]Our findings further indicated that mesenchymal cells can also differentiate into cells of endodermal origin. No evidence was provided to show that the limited results were attributed to fibroblasts. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that fibroblasts in cirrhotic liver can differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells with comprehensive phenotypic and functional characteristics.

In conclusion, our findings indicated that human fibroblasts in cirrhotic liver exhibited stem cell phenotypes and differentiation potential to hepatocyte-like cells in vitro and in vivo, which implied the process of MET. Because of the similarities in the biological characteristics and surface markers, we could not exclude the possibility of MSC contamination in hepatic fibroblasts in our experiments, and serial studies on cell tracing are ongoing in our lab. Nonetheless, our results shed new light on the effect of hepatic fibroblasts in the process of liver fibrosis and continue to challenge the perspective of the restricted differentiation potential of adult-derived stem cells. Most important of all, these studies indicated the plasticity of fibroblasts from cirrhotic liver, inferring a new target for hepatic fibrotic reversion and providing potential avenues for application of these fibroblasts, such as tissue engineering.

Funding:This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (2009CB522403), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT0753), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30801327), and National Key Scientific and Technological Research program (2008ZX10002-022).

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Contributors:SYL and YSY designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the study and to further drafts. ZSS is the guarantor.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Azar N, Valla D, Abdel-Samad I, Hoang C, Fretz C, Sutton L, et al. Liver dysfunction in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation recipients. Transplantation 1996;62:56-61.

2 Locasciulli A, Testa M, Valsecchi MG, Vecchi L, Longoni D, Sparano P, et al. Morbidity and mortality due to liver disease in children undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a 10-year prospective study. Blood 1997;90: 3799-3805.

3 Young HE, Steele TA, Bray RA, Hudson J, Floyd JA, Hawkins K, et al. Human reserve pluripotent mesenchymal stem cells are present in the connective tissues of skeletal muscle and dermis derived from fetal, adult, and geriatric donors. Anat Rec 2001;264:51-62.

4 Woodbury D, Reynolds K, Black IB. Adult bone marrow stromal stem cells express germline, ectodermal, endodermal, and mesodermal genes prior to neurogenesis. J Neurosci Res 2002;69:908-917.

5 Liechty KW, MacKenzie TC, Shaaban AF, Radu A, Moseley AM, Deans R, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells engraft and demonstrate site-specific differentiation after in utero transplantation in sheep. Nat Med 2000;6:1282-1286.

6 Malhi H, Irani AN, Gagandeep S, Gupta S. Isolation of human progenitor liver epithelial cells with extensive replication capacity and differentiation into mature hepatocytes. J Cell Sci 2002;115:2679-2688.

7 Herrera MB, Bruno S, Buttiglieri S, Tetta C, Gatti S, Deregibus MC, et al. Isolation and characterization of a stem cell population from adult human liver. Stem Cells 2006;24: 2840-2850.

8 Sgodda M, Aurich H, Kleist S, Aurich I, K?nig S, Dollinger MM, et al. Hepatocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from rat peritoneal adipose tissuein vitroandin vivo. Exp Cell Res 2007;313:2875-2886.

9 Gilgenkrantz H. Mesenchymal stem cells: an alternative source of hepatocytes? Hepatology 2004;40:1256-1259.

10 Lee KD, Kuo TK, Whang-Peng J, Chung YF, Lin CT, Chou SH, et al.In vitrohepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Hepatology 2004;40:1275-1284.

11 Kakinuma S, Tanaka Y, Chinzei R, Watanabe M, Shimizu-Saito K, Hara Y, et al. Human umbilical cord blood as a source of transplantable hepatic progenitor cells. Stem Cells 2003;21:217-227.

12 Herzlinger D. Renal interstitial fibrosis: remembrance of things past? J Clin Invest 2002;110:305-306.

13 McAnulty RJ. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts: their source, function and role in disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007;39: 666-671.

14 Wagner W, Wein F, Seckinger A, Frankhauser M, Wirkner U, Krause U, et al. Comparative characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood. Exp Hematol 2005;33:1402-1416.

15 Brendel C, Kuklick L, Hartmann O, Kim TD, Boudriot U, Schwell D, et al. Distinct gene expression profile of human mesenchymal stem cells in comparison to skin fibroblasts employing cDNA microarray analysis of 9600 genes. Gene Expr 2005;12:245-257.

16 Ishii M, Koike C, Igarashi A, Yamanaka K, Pan H, Higashi Y, et al. Molecular markers distinguish bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells from fibroblasts. Biochem BiophysRes Commun 2005;332:297-303.

17 Rutherford RB, Gu K, Racenis P, Krebsbach PH. Early events: thein vitroconversion of BMP transduced fibroblasts to chondroblasts. Connect Tissue Res 2003;44:117-123.

18 Rutherford RB, Moalli M, Franceschi RT, Wang D, Gu K, Krebsbach PH. Bone morphogenetic protein-transduced human fibroblasts convert to osteoblasts and form bonein vivo. Tissue Eng 2002;8:441-452.

19 Shui C, Scutt AM. Mouse embryo-derived NIH3T3 fibroblasts adopt an osteoblast-like phenotype when treated with 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) and dexamethasonein vitro. J Cell Physiol 2002;193:164-172.

20 Wells RG. Cellular sources of extracellular matrix in hepatic fibrosis. Clin Liver Dis 2008;12:759-768, viii.

21 Larsson O, Diebold D, Fan D, Peterson M, Nho RS, Bitterman PB, et al. Fibrotic myofibroblasts manifest genome-wide derangements of translational control. PLoS One 2008;3: e3220.

22 Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1655-1669.

23 Plotkin MD, Goligorsky MS. Mesenchymal cells from adult kidney support angiogenesis and differentiate into multiple interstitial cell types including erythropoietin-producing fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006;291:F902-912.

24 Sabatini F, Petecchia L, Tavian M, Jodon de Villeroché V, Rossi GA, Brouty-Boyé D. Human bronchial fibroblasts exhibit a mesenchymal stem cell phenotype and multilineage differentiating potentialities. Lab Invest 2005;85:962-971.

25 Sheng W, Wang G, La Pierre DP, Wen J, Deng Z, Wong CK, et al. Versican mediates mesenchymal-epithelial transition. Mol Biol Cell 2006;17:2009-2020.

26 Dezso K, Jelnes P, László V, Baghy K, B?d?r C, Paku S, et al. Thy-1 is expressed in hepatic myofibroblasts and not oval cells in stem cell-mediated liver regeneration. Am J Pathol 2007;171:1529-1537.

27 Lysy PA, Smets F, Sibille C, Najimi M, Sokal EM. Human skin fibroblasts: From mesodermal to hepatocyte-like differentiation. Hepatology 2007;46:1574-1785.

28 Laconi S, Curreli F, Diana S, Pasciu D, De Filippo G, Sarma DS, et al. Liver regeneration in response to partial hepatectomy in rats treated with retrorsine: a kinetic study. J Hepatol 1999;31:1069-1074.

29 Gordon GJ, Coleman WB, Hixson DC, Grisham JW. Liver regeneration in rats with retrorsine-induced hepatocellular injury proceeds through a novel cellular response. Am J Pathol 2000;156:607-619.

30 Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2005;115: 209-218.

31 Saalbach A, Wetzig T, Haustein UF, Anderegg U. Detection of human soluble Thy-1 in serum by ELISA. Fibroblasts and activated endothelial cells are a possible source of soluble Thy-1 in serum. Cell Tissue Res 1999;298:307-315.

32 Forbes SJ, Russo FP, Rey V, Burra P, Rugge M, Wright NA, et al. A significant proportion of myofibroblasts are of bone marrow origin in human liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2004;126:955-963.

33 Suskind DL, Muench MO. Searching for common stem cells of the hepatic and hematopoietic systems in the human fetal liver: CD34+ cytokeratin 7/8+ cells express markers for stellate cells. J Hepatol 2004;40:261-268.

34 Bussolati B, Bruno S, Grange C, Buttiglieri S, Deregibus MC, Cantino D, et al. Isolation of renal progenitor cells from adult human kidney. Am J Pathol 2005;166:545-555.

35 Katz AJ, Tholpady A, Tholpady SS, Shang H, Ogle RC. Cell surface and transcriptional characterization of human adipose-derived adherent stromal (hADAS) cells. Stem Cells 2005;23:412-423.

36 Yu Y, Fuhr J, Boye E, Gyorffy S, Soker S, Atala A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and adipogenesis in hemangioma involution. Stem Cells 2006;24:1605-1612.

37 Sicklick JK, Choi SS, Bustamante M, McCall SJ, Pérez EH, Huang J, et al. Evidence for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in adult liver cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2006;291:G575-583.

38 Zeisberg M, Yang C, Martino M, Duncan MB, Rieder F, Tanjore H, et al. Fibroblasts derive from hepatocytes in liver fibrosis via epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem 2007;282:23337-23347.

39 Kaimori A, Potter J, Kaimori JY, Wang C, Mezey E, Koteish A. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces an epithelial-tomesenchymal transition state in mouse hepatocytesin vitro. J Biol Chem 2007;282:22089-22101.

40 Prindull G, Zipori D. Environmental guidance of normal and tumor cell plasticity: epithelial mesenchymal transitions as a paradigm. Blood 2004;103:2892-2899.

41 Miettinen PJ, Ebner R, Lopez AR, Derynck R. TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: involvement of typeireceptors. J Cell Biol 1994;127:2021-2036.

42 Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2002;110:341-350.

43 Ishii T, Yasuchika K, Fujii H, Hoppo T, Baba S, Naito M, et al.In vitrodifferentiation and maturation of mouse embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes. Exp Cell Res 2005;309:68-77.

44 Jung J, Zheng M, Goldfarb M, Zaret KS. Initiation of mammalian liver development from endoderm by fibroblast growth factors. Science 1999;284:1998-2003.

45 Lindroos PM, Zarnegar R, Michalopoulos GK. Hepatocyte growth factor (hepatopoietin A) rapidly increases in plasma before DNA synthesis and liver regeneration stimulated by partial hepatectomy and carbon tetrachloride administration. Hepatology 1991;13:743-750.

46 Suzuki A, Iwama A, Miyashita H, Nakauchi H, Taniguchi H. Role for growth factors and extracellular matrix in controlling differentiation of prospectively isolated hepatic stem cells. Development 2003;130:2513-2524.

47 Forte G, Minieri M, Cossa P, Antenucci D, Sala M, Gnocchi V, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor effects on mesenchymal stem cells: proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Stem Cells 2006;24:23-33.

October 14, 2010

Accepted after revision December 17, 2010

Author Affiliations: Key Lab of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, and Digestive Organ Transplantation of Henan Province, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhengzhou University School of Medicine, Zhengzhou, China (Sun YL); and Key Lab of Combined Multi-organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health and Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China (Yin SY, Zhou L, Xie HY, Zhang F, Wu LM and Zheng SS)

Shu-Sen Zheng, MD, PhD, FACS, Key Lab of Combined Multi-organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health, and Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China (Tel: 86-571-87236570; Fax: 86-571-87236466; Email: shusenzheng@ zju.edu.cn)

? 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2011年1期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2011年1期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Primary hepatic carcinosarcoma

- Aberrant methylation frequency of TNFRSF10C promoter in pancreatic cancer cell lines

- Protective effects of glutamine preconditioning on ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats

- Effects of suppressing glucose transporter-1 by an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide on the growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells

- Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits hepatic fibrosis in rats